Glengarry Glen Ross is one of those films that flew under the radar because of its ultra low-budget look and feel. As moviegoers, when we don’t see our movie stars perfectly lit in front of A-level sets, we get suspicious. “Is this one of those vanity projects?” we ask? The kind where the acting is great but the story sucks? We’ve been burned by too many of those before so no thanks. But Glengarry is one of the few “vanity” projects that was also a great story (and a great film!). I mean superstar screenwriter David Mamet (who was paid 1 million to turn his hit play into a script) wrote the thing. And to many, this is his best work. There are, of course, three things that one remembers from Glengarry – Jack Lemon’s amazing performance, The Alec Baldwin scene (which was written exclusively for the film – it was not in the play) and the razor-sharp dialogue. In honor of that dialogue, I’ve decided to make today’s “10 Tips” all dialogue-related! Enjoy!

1) Your characters should only speak when they have something to say – Without question, one of the biggest mistakes I see from amateurs is characters who are only talking because they’re in a scene. If characters are only talking because a writer’s making them, the scene will be maddeningly boring. What’s so great about Glengarry Glenn Ross is that the characters never say anything unless they want something. They may want to close a deal, they may want to beg for leads, they may want to let their boss know how pissed they are, they may want to vent their frustrations to their co-workers, they may want to convince someone to steal the leads with them. But they’re always speaking for a reason. If your character doesn’t want anything, they probably shouldn’t be saying anything.

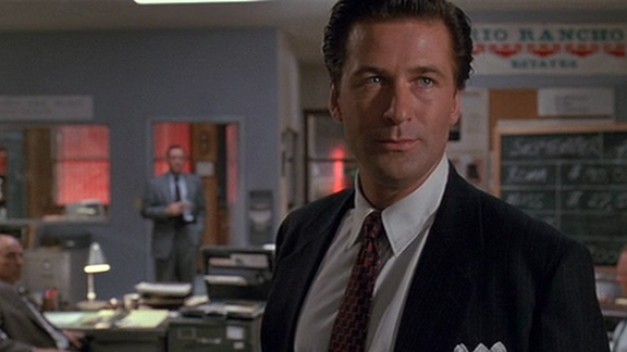

2) Use dialogue to reveal character whenever possible – When characters speak, try to occasionally tell us something about their character via dialogue. For example, Blake (Alec Baldwin) is gearing up for his classic monologue early in the script. He turns to Williamson (Kevin Spacey). “Are they all here?” “All but one.” “(checks watch) Well, I’m going anyway.” In other words, this is the kind of man who doesn’t have time to wait for others. That’s what we learn about Blake through this line of dialogue. You should try to reveal character through dialogue wherever you can.

3) Ask and you shall receive… a better response – When a character asks another character a question, the simplest answer is usually the most boring. “How are you?” “Good. How bout you?” If this is how your characters speak, God help you. You can do better. In the famous Blake (Alec Baldwin) monologue, one of the salesmen asks, “What’s your name?” “Fuck you, that’s my name. You know why, Mister? ‘Cause you drove a Honda to get here tonight, I drove a sixty-thousand dollar B.M.W. That’s my name (original dialogue).” What would you have written had someone asked Blake “What’s your name?” Hopefully something just as unique.

4) Specificity in monologues – Monologues, like Alec Baldwin’s, work best when the speaker is being SPECIFIC. This monologue would’ve sucked had the character unleashed something general like: “You guys are all lazy bums! We give you leads and what do you do with them? Jack shit! You need to stop fucking around and work harder to secure these guys!” There’s no specificity there. Anyone could’ve written that! In Mamet’s version, we learn about ABC (Always be closing), A.I.D.A (Attention, Interest, Decision, Action), we learn Blake drives a 60 thousand dollar BMW, we learn his watch costs more than what these guys make in a year, we learn he’s from Mitch and Murray, we learn about the coveted sparkling wonderful Glengarry leads. The monologue is convincing because it’s not just a bunch of general bullshit. It covers a lot of details. Make sure to do the same with your monologues.

5) Delay an answer to a question! – Just because a character asks a question during a conversation doesn’t mean the other character has to answer it right away. We see this during another great moment in the Blake monologue. Moss (Ed Harris) challenges Blake with, “You’re such a hero, you’re so rich, how come you’re coming down here, waste your time with such a bunch of bums?” Blake looks at him for a moment then keeps on yelling at everyone. A few minutes later, out of nowhere, he turns back to Moss: “And to answer your question pal. Why am I here? I came here because Mitch and Murray asked me to, they asked for a favor, I said the real favor, follow my advice, and fire your fuckin ass, because a loser is a loser.” A conversation is never a straightforward thing. It jumps around a lot. Never forget that.

.

6) CONFLICT CONFLICT CONFLICT – I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. One of the easiest ways to create good dialogue is through conflict. In almost every single scene in Glengarry Glen Ross, one character wants something while the other character wants something else. Take the famous scene where Shelley Levene (Jack Lemmon) begs Williamson (Kevin Spacey) for the Glengarry leads. The entire scene is built on the principle that Levene desperately wants those leads while Williamson is determined not to give them to him.

7) Phrase exercise – To find out your character’s unique way of speaking, take a simple phrase, then have your characters each say it in their own unique way. This is not to happen in the script. Do this in a separate document. The goal is to get a feel for how each of your characters speak. Take the phrase, “Good luck.” Let’s see how each of the characters in Glengarry would say this. Blake actually says in the script, ““I’d wish you good luck but you wouldn’t know what to do with it.” Bitter Shelley might say, “Good luck you miserable cocksucker.” Pathetic Williamson might say, “Good luck” laced with heavy sarcasm. Earnest Aaronow (Alan Arkin) might say, “Best of luck, Frank. You deserve it. You really do.” If each of your characters wouldn’t have their own way of saying a phrase, you either don’t know your characters well enough or you’re not doing enough with your dialogue.

8) A negative temperament for at least one character in a scene typically results in interesting dialogue – Some of the best scenes in Glengarry are when Shelley (Jack Lemon), wreaking of desperation, tries to get others to do what he wants (getting those Glengarry leads, trying to get the husband of the woman he talked to on the phone to come around). Whether it be frustration, desperation, fear, anger – Negative dispositions are your friends when writing dialogue.

9) Liar Liar, dialogue on fire – Dialogue is always interesting when someone’s lying. Why? There’s a natural inclination for us readers to find out if the other party’s going to figure it out or not. Glengarry is one big lying fest. Shelley’s lying to all the leads about how they “won” a contest. Roma (Pacino) spends the entire movie lying to his mark. Ross (Ed Harris) and Aaronow (Alan Arkin) are lying about robbing the place. When a character has something to hide, the dialogue always has an extra spark to it.

10) Give your character an interesting angle going into a scene – Instead of just placing two characters in a scene and letting them talk, try to find an interesting angle for your key character. So in the Glengarry restaurant scene, where Roma (Al Pacino) is trying to con a customer into a sale, there’s a million ways Mamet could’ve approached it. He could’ve had Roma be straight forward, he could’ve used the hard sell, he could’ve had him focus exclusively on the numbers, he could’ve made it seem like a great deal then played hard to get. Instead, he has Roma SEDUCE the man. He treats him like a date, someone he’s wooing. He slowly cuddles up to him, makes the man believe in him, and that’s when he goes in for the kill. Seduction, I believe, was the best option for interesting dialogue in this case. It allowed for all this fun philosophizing on life that you wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. If you want good dialogue, make sure your character is approaching what he wants from an interesting angle.