Search Results for: mena

Is this the best sci-fi fantasy short story ever written?

Genre: Short Story – Drama/Fantasy

Premise: A young half-Chinese half-American boy struggles to connect with his Chinese mother, who doesn’t speak English.

About: This is a multiple award-winning short story by Ken Liu from his short story collection, “The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories.” You can find it on Amazon. I don’t think the short story can be found anywhere online, unfortunately.

Writer: Ken Liu

Details: Around 4000-5000 words

Ken Liu is really starting to blow up. The team that made 2018’s, “The Arrival,” is turning one of his short stories, “The Message,” about an alien archaeologist who studies extinct civilizations and reunites with a daughter he never knew he had, into a film. AMC is developing a series based on his short stories called Pantheon. You also have Game of Thrones creators David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, adapting Ken Liu’s English translation of the epic sci-fi novel, “The Three Body Problem,” (which won the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel, making it the first translated novel to have won the award) for Netflix.

When I started looking into Liu, I learned that his big blow-up moment came upon the release of the short story, The Paper Menagerie. That story achieved something that had never been done before, which is sweep the Hugo, Nebula and World Fantasy writing awards. Everybody says this short story is amazing.

Which has inspired a secondary question as I go into this review. If this is his best work, why isn’t anyone trying to adapt it? There might be an obvious answer to this by the time I finish (some stories just aren’t easy to adapt) or, if not, maybe this article will be the impetus for someone finally buying it.

With that in mind, let’s do this!

(by the way, this story is best enjoyed without knowing anything so I’d suggest reading it first if possible)

Jack is a young boy who lives in Connecticut with his American father and Chinese mother. Jack informs us right away that his father found his mom “in a catalog” for Chinese women looking for American husbands. Even at this young age, Jack considers this weird and something to be ashamed of.

Because his mother was a Chinese peasant, she doesn’t know any English. She tries. But the words never come out right and she becomes embarrassed. Because his father makes him, Jack learns Mandarin, but he resents that his mother isn’t trying harder to learn English, and therefore refuses to speak her native tongue.

However, Jack’s mother finds another way to communicate with her son. One of the skills she learned from her village was creating special origami animals that are alive!

His family, being poor, couldn’t afford the fancy toys at the time (like all the Star Wars figures) so these origami animals became his toys. He would play with them for hours in his room, never tiring of them.

But when he became a teenager, his resentment for his mother skyrocketed. All this time and she still hadn’t properly learned English, meaning she couldn’t have a conversation with anyone, even her own son. Jack began talking to his mom less and less and even boxed away all her origami animals and threw them in the attic.

During his college application process, his mom gets sick. Her insistence to not be a bother to anyone had meant, by the time she checked in with a doctor, her cancer had spread too far to be treated. Even at this moment, Jack could not muster up any emotion for his mother. Here he was about to pick a college and his mom was still finding a way to mess it up. When he goes out to school in California, his mother dies.

Years later, Jack’s girlfriend finds his old box of origami animals and after she leaves for the day they, once again, come alive. Jack plays with them and it’s just like he was a kid again. Then he spots something on his favorite animal. As he unfolds it, he realize his mother has written a note inside. But it’s in Chinese. So Jack goes to someone who can translate it for him, and the woman reads his mother’s letter to Jack, which tells him the full story of her devastating childhood and how her life was meaningless until he showed up in it.

Okay.

I challenge anyone to read this story and not start bawling from the get-go. This is the saddest story ever. But good sad. “Gets to the heart of broken mother-son relationship” good sad.

I read a lot of screenplays that try to make you cry. Rarely do they achieve it. People think all you need to do to make a reader cry is give someone cancer. Have them die before ever saying “I love you” and people will eat it up. Making people cry is surprisingly difficult. There’s something about the act of trying to make someone cry that keeps them from crying. It’s almost like they know what you’re up to. For emotion to hit on that level, it has to feel like real life. Not like a writer trying to manipulate your emotions.

But one thread that seems to be present in a lot of cry movies is an unresolved family relationship. It could be a man and his wife, a father and daughter, a sister and brother, or, in this case, a mother and son.

I’m not going to pretend like I know the exact code for why this worked because I think nailing an emotionally brilliant story is always going to be a “lightning in a bottle” scenario. But I found it interesting that Liu reversed the typical roles in this kind of story. Instead of the parent being the one who disassociates from the child, it’s the child who pulls away from the parent. And for, whatever reason, that’s more heartbreaking. A child isn’t supposed to despise his mother.

That’s also a big reason why we’re turning the pages. Whenever you set up an unresolved scenario between two characters, we’re naturally going to want that relationship to be mended. It’s painful to walk away from something this emotionally powerful without knowing how it ends. Just by setting this scenario up, you’ve ensured that we’re going to read the full story.

But where Paper Menagerie separates itself from the 10 million other stories that have also tried and failed to make you weep, is this “strange attractor” in the origami animals. The story isn’t just mom and son arguing every day, which is the typical scenario I encounter in similar setups. The mom speaks to Jack through the animals. They become the only way the two communicate. And that adds a special element that elevates the story.

Another small detail was the meanness of Jack. Now, normally, you don’t want your main character to be mean. Once you cross a certain threshold of un-likability for your protagonist, the reader dislikes them and no longer cares about their journey.

What this does is it scares writers into always writing nice protagonists. The problem with that is that there’s nobody on the planet who’s perfect. We’re all flawed. We all have unpopular opinions. Mean thoughts. And if you take that arena away from your hero, you also take away their truth. You are now constructing something that doesn’t exist. And readers pick up on that.

The reason why it works here is because WE UNDERSTAND WHY JACK FEELS THIS WAY. That’s the key to making “mean” protagonists work. As long as we understand where their anger or meanness comes from, or, even better, we can relate to it in some way, then the meanness is going to work.

Jack is lonely. He is half-Chinese in a town where there are no other Chinese kids. Everyone knows his mom was purchased. When friends come over, his mom never speaks because she doesn’t know English. As a kid, this is embarrassing. Cause you have to deal with the effects of that every day. Of course you’re going to have resentment towards your mother. Once you’ve grounded the central story emotions in that reality, you’re golden. Because now we believe what we’re reading to be true and our focus shifts to, “Will this broken bridge ever be mended?”

Finally, I want to talk about the big final letter. The “final letter” scenario is actually something I see quite a bit in screenplays. Everyone thinks they’re being original when they do it but, trust me, it’s not original. And most of these writers fail gloriously with these letters. The reason being that they write something too obvious. “I always loved you. I think you’re going to become an amazing person. I wish we could’ve been closer but I’ve learned with time we will always be together spiritually… blah blah blah.”

This letter hit on some of those things, but it wrapped them around two key choices that elevated the letter beyond your typical “end of movie letter moment.” The first was she told the story of her childhood. Again, most writers are thinking literally: “I need to have mother tell son how she feels.” That’s obvious and rarely works. So to instead talk about her childhood shifts the focus away from her feelings about him and tells us about her. It was unexpected and her background was so detailed and interesting that it was almost like a story in itself we wanted to know the ending to.

The second thing Liu does (spoiler) is that the letter doesn’t end on a happy note. It isn’t one of those, “Go out there and seize the day!” endings. It’s more of a, “I was devastated we could never communicate and I always wished you gave me more of a chance” endings. That simple shift takes this from a perfect wrapped–in-a-bow Hollywood ending to something more realistic, more true to life.

I see now why everyone went nuts for this. It’s almost a perfect story. I don’t think they can turn it into a movie though. It works because its short form allows it to stay hyper-focused on the relevant variables (the mom, the origami animals). Once you extrapolate that and add a bunch of other plot, the concept becomes distilled and the animals don’t make as much sense.

I don’t know. Maybe someone would be able to figure it out. I’m surprised no one’s tried. Like I said earlier, maybe they will now.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: Ken Liu has an interesting philosophy in how he treats his first draft. He calls it the “Negative First Draft.” Here is his explanation to tor.com. – I usually start with what I call the negative-first draft. This is the draft where I’m just getting the story down on the page. There are continuity errors, the emotional conflict is a mess, characters are inconsistent, etc. etc. I don’t care. I just need to get the mess in my head down on the page and figure it out.The editing pass to go from the negative-first draft to the zeroth draft is where I focus on the emotional core of the story. I try to figure out what is the core of the story, and pare away all that’s irrelevant. I still don’t care much about the plot and other issues at this stage.

The pass to go from zeroth to first draft is where the “magic” happens — this is where the plot is sorted out, characters are defined, thematic echoes and parallels sharpened, etc. etc. This is basically my favorite stage because now that the emotional core is in place, I can focus on building the narrative machine around it.

Genre: Biopic

Premise: In the 80s, a rogue pilot becomes Ground Zero for the majority of the cocaine being smuggled into the US. The crazy thing? He’s being funded by the United States government.

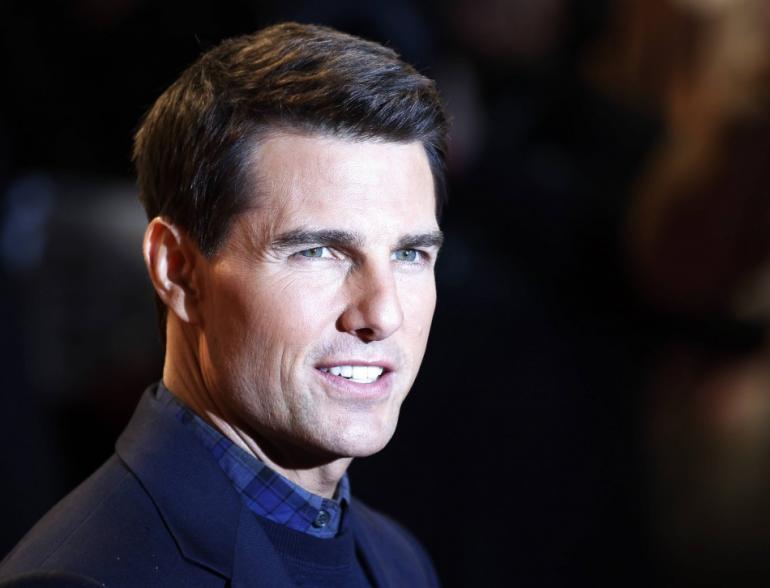

About: This was a huge “spec” package early last year. Sold for 7 figures with Ron Howard attached to direct. It’s since nabbed Tom Cruise as the lead to play Barry Seale and Doug Liman (who teamed with Cruise on Edge of Tomorrow) to take over directing duties. The script also finished in the top 10 of the most recent Black List. I remember reading Spinelli’s breakthrough spec five years ago – a clever idea about a man who kidnapped criminals and auctioned them off to rival crime bosses. It didn’t put him on the top of any studio’s list, but it got the town’s attention. He kept writing and, five years later, nabbed one of the top 3 spec sales of the year. It just goes to show that you’re playing the long game here. Break through with a cool spec, don’t celebrate, put your nose back to the grindstone, keep writing, keep generating material, get more and more people familiar with your work. Then one day, that opportunity presents itself for a huge payday and the ultimate goal of being a produced writer.

Writer: Gary Spinelli.

Details: 128 pages – 10/26/13 draft

It’s a new world. A biopic world. After American Sniper, scripts like Mena, Jobs, and that McDonald’s movie are top priority for studios sick of working on the next actors-in-tights SFX fiasco (I mean seriously – is anyone really that excited to work on Wonder Woman?). Now I could go on my rant about why I’m not a huge fan of biopics, but the first half of Mena makes my argument for me.

There isn’t a single dramatized scene in the first 67 pages of this screenplay. The entire first half of the script is voice over and exposition. This doesn’t seem to bother some people and I can’t for the life of me figure out why. It’s nice to learn fun tidbits about how we stole weapons from Palestine, then sold them to secretly win wars in South America. But unless you give me a few scenes with some actual suspense mixed in, I’m going to have a hard time staying awake.

But hey, I was singing the same uninspired tune after reading American Sniper. And look how that turned out. This could be a very good omen for Ron Howard and Co.

Mena follows our adrenaline junkie hero, TWA pilot Barry Seale, through the 1980s, when he realizes he wants something more out of life. Being a commercial pilot pays well. But “light rain” on the runway is hardly enough excitement to get Barry up in the morning.

So when Barry gets an offer from the CIA to fly small planes through South America to track revolutionary movements there, he takes it. Being opportunistic, Barry then uses the contacts he makes in South America to smuggle cocaine back into the U.S.

Thinking he’s sly, Barry is shocked to find out that the CIA knew what he was doing all along. In fact, they orchestrated it! By having someone in tight with the cartels of South America, it allows them to influence the factions of government that run things down there. They also start using the money Barry makes from the drug running to purchase stolen weapons from the Palestinian war and sell those weapons to U.S. friendly forces down in South America.

Confused? I sure as hell was.

Anyway, a local cop in the tiny town Barry lives in starts to suspect that Barry is a shady character (could it be the giant mansion he’s built in the cash-strapped town?) and begins looking into his suspicious activities. To make matters even more complicated, the president at the time, Ronald Reagan, declares a war on drugs, seeking to destroy operations like Barry’s, despite the fact that he’s unofficially funding him!

The next thing Barry knows, the FBI is moving into town. The attorney general wants to know what’s up. And Barry’s supposedly untouchable operation is at risk of imploding, bringing down himself, the South American drug trade, and the CIA. You can bet your ass though, that when those organizations are threatened, the last person they’re going to be thinking of protecting is Barry Seale.

Clearly, this was written with the hopes of getting Scorsese to direct. It’s got his signature “Mythology Breakdown” opening, where he over-examines the intricacies of the subject matter via copious amounts of voice over. Instead of Scorsese, though, we get Doug Liman. Which, while no Scorsese, is still an upgrade over Ron Howard. Ron Howard trying to pull off a Scorsese film is a little like Nicholas Sparks trying to write Fight Club.

Here’s my big issue with Mena, regardless of who’s making it. Barry’s external life is an interesting one. He’s robbing the very government he’s working for. He’s using his drug connections to make himself rich. He’s delivering weapons that are shaping the future of South America.

But go ahead and read back those accomplishments. They’re all EXTERNAL. It’s not Barry who’s interesting. It’s the situations he finds himself in that are interesting. Barry himself is a pretty basic dude. There’s no real conflict within him. He’s not battling any demons. His relationship with his family is practically an afterthought (at least in this draft). So what is Barry dealing with on an internal level?

At least with Chris Kyle in American Sniper, you could feel a battle raging inside of our protagonist. He’s been made a hero for killing people –in some cases children. And he struggles to come to terms with that. I guess I wanted more of a character study in Mena and not just two hours of “look at all this crazy shit that’s happened to me.” Especially because we’re not so much being SHOWN this crazy shit as we’re given an audio play-by-play of it.

Earlier I was talking about the lack of a dramatized scene until page 67. What did I mean by that? Well, the first 67 pages of Mena consist of Barry laying out the bullet points of how he smuggled drugs and ran weapons back and forth between the Americas. There wasn’t a single scene between characters that consisted of an unknown outcome.

Finally, on page 67, Barry is tasked with having to kill his brother-in-law and partner, who’s been captured by the police. After getting him out on bail, Barry plans to take his partner out to the desert and kill him. FINALLY! A SCENE WITH SOME FUCKING SUSPENSE! It was the first time I actually leaned in and was excited to see what happened next. For once, there wasn’t a Wikipedia voice over yapping away at me.

And that’s how I like my stories told. I like when writers set up uncertain situations that hook us into wanting to read more. I get that we have to set SOME story up first but, man, 67 pages is an awful long time to set up story.

There’s definitely something to Barry Seale. There are too many wacky components to his life to call this an ill-informed project. But we must remember that while the external stuff is always fun, it’s not what’s going to emotionally hook an audience. If you’re writing a biopic, you’re saying that first, and foremost, this is a character study. So give us a study of the character. Not just the shit he gets into.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A great way to write a suspenseful (dramatized) scene is to follow this formula:

a) Create a problem that results in a difficult choice for your main character.

b) Make the stakes of that problem as high as you can.

c) Have the outcome of this issue completely unknown.

d) Draw the scene out as long as you can.

This is why that scene on page 67 brought my full attention to the script for the first time.

a) Barry knows the only way to keep his step-brother quiet is to kill him.

b) If Barry doesn’t kill him, the CIA and the Columbians will come after Barry.

c) We sense Barry is going to kill his step-brother but we don’t know for sure.

d) This all plays out over a long car ride from the jail to the desert.

In honor of the year 2015, the year Star Wars returns to theaters, I’ll be writing a series of articles throughout the year to celebrate (and occasionally eviscerate), the greatest franchise ever. Enjoy! And may Christmas 2015 come faster than it takes Han Solo to do the Kessel Run.

The year was 1999. For movie nerds, that year marked the arrival of the single most anticipated film in movie history. It was the year The Phantom Menace came out. As millions of Star Wars fans left their local theater confused about how the magic of Star Wars could disappear faster than a womp rat on meth, I went back to my apartment looking for answers. Did George Lucas really just turn my favorite franchise into a bad Saturday morning cartoon?

In the time since, a lot has been dedicated to explaining why the movie didn’t work. But one of the things that doesn’t get mentioned that often – if it all – is the featured set-piece in the movie: the Pod Race.

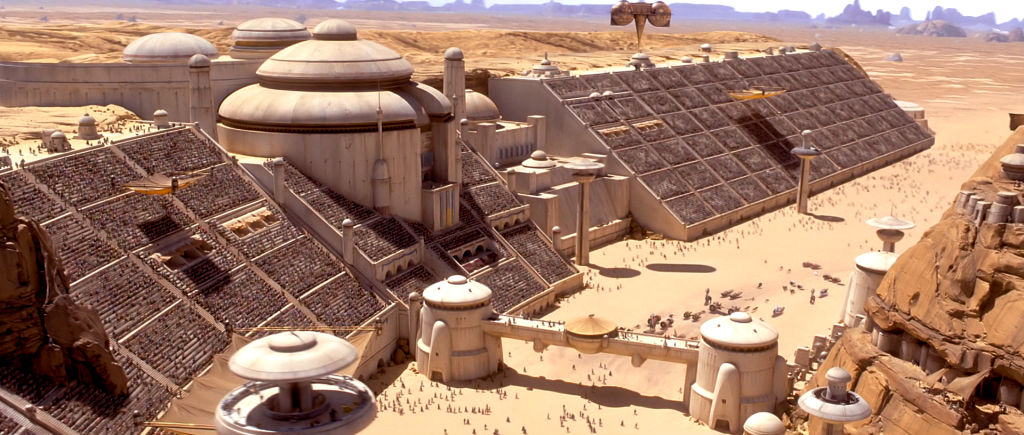

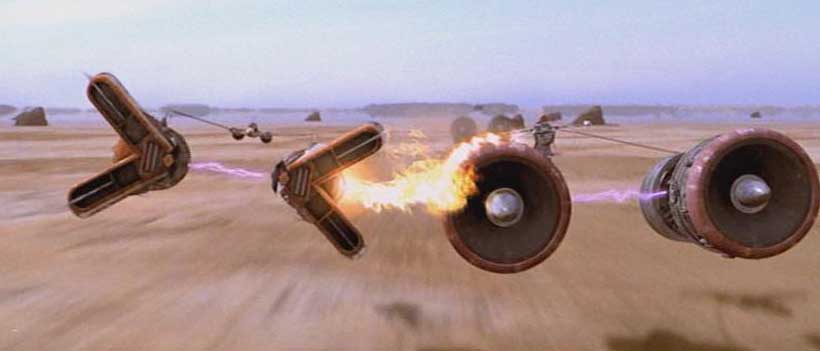

The Pod Race, in George Lucas’s mind, WAS the movie. While good ole George was excitedly grinding everything from characters to sets into his digital blender, the Pod Race was the one thing he actually built stuff for. Every one of the vehicles in that race was a real prop.

So why is it, then, that a set-piece given so much attention, given so much screen time, given so much weight in the film, turned out to be one of the most boring races (and set-pieces) ever put on film? You watch that race and you’re not focusing on whether Anakin is going to win or not. You focus on why everything is so fucking boring.

The answer to this – once learned – will ensure that you never write a bad set-piece again (or at least one as bad as this). To be honest, set-pieces are typically one of the more boring parts of a screenplay. They’re often cut-and-dry “car speeds up, cuts other car off, joey shoots, brad ducks” blueprint-oriented scenes, rather than scenes written to actually evoke emotion (huge mistake). Truth be told, a lot of execs skim over set-pieces because there’s no important story information in them and it allows them to finish the read quicker.

If you’re doing your job, a reader will never EVER want to skim past a scene. They’ll be so caught up in your characters and your story that every little moment in that set-piece matters to them! So what did screenwriter George Lucas do so terribly to make this sequence, which should’ve been one of the classic all-time action scenes, so boring? Five things, to be exact. Let’s take a look at them.

“BORING MAIN CHARACTER” – I honestly don’t care if you’re the greatest set-piece writer in the world. If we don’t care about the person who’s at the center of the set piece, nothing you write in the set-piece will matter. I say this again and again on the site, but writers never do anything about it! Stop putting all your time into the set-piece and put it into creating an original, compelling, entertaining main character who we want to root for. Star Wars could’ve turned The Pod Race into a Bobbing For Apples contest and it would’ve worked if we cared about Anakin.

“NO MAIN CHARACTER FLAW” – In my newsletter, I talked about the importance of dealing with your characters’ internal issues in external ways. There’s no better time to do this than in a set-piece. And there’s no better way to explore it than through your hero’s unique flaw. If you’re going to build a ten minute race scene into your movie, it better challenge your hero’s flaw in some way. The problem here? Annakin didn’t have a flaw. He had some doubts, some fears. But he didn’t have a clear flaw. In contrast, Luke Skywalker didn’t fully believe in himself. That was his flaw. And that’s why him trusting himself in that ending Death Star sequence was so goose-bump inducing. A clear character flaw equals clear “external conflict” to play with during set-pieces, which creates a closer emotional connection between movie and viewer.

“THE BULLSHIT ARTIST” – Set pieces are your movie’s big performance numbers. In an action movie, they will often be what your movie is remembered for. So their reason for existing has to be airtight. The Rebels didn’t attack the Death Star in the first Star Wars, for example, because someone had a hunch that the base had a weakness. They had the Death Star plans that told them exactly how to destroy the base. In The Phantom Menace, we’re sold some cheap B.S. that winning this pod race (and using the prize money to fix their broken ship) was the only way for our group to get off the planet. As if two of the most important Jedi in the galaxy couldn’t have found an alternative way to leave. Once we know you’re trying to bullshit us on the reasoning for a set-piece’s existence, we turn on you quickly.

“OVER-COMPLICATION” – One of the things I continue to see amateur writers do wrong is needlessly overcomplicate their stories. Stop. Just stop! There’s always a simpler way. What you do when you over-complicate something, is you create confusion in the reader. If the reader is confused about why a big set-piece is going on, nothing in the set-piece matters. Before the Pod Race, Lucas injects an incredibly complicated bet between Qui-Gon and a local alien gambler that states if Anakin loses, the alien gets the pod-racer, but if Qui-Gon wins, he gets the pod racer, Anakin, and a part for his broken ship. The alien then doubles down, and if he wins, he gets the ship, the pod racer, the Anakin, and possibly Qui-Gon too. Qui-Gon comes back at him and doubles his own bet by asking for Anakin’s mom if they win as well. It’s so needlessly confusing, that by the time the race starts, we’re clueless as to what needs to happen. Confusion is NEVER EVER EVER good for your story and is especially bad right before a major sequence.

“REPETITION” – A set-pieces’ mortal enemy is repetition. If the cars that are chasing each other are doing the same dance for too long or if the bad guys and the good guys continue to shoot and duck in the same way over and over, we’re going to lose interest. A set-piece is a mini-movie. And just like any movie, you need to challenge and surprise your audience over and over again. Treat your set-piece like your portfolio and diversify. In the Pod Race, we were subjected to the same desert checkpoints again and again with little variety in the action or interactions between racers.

To me, the worst set-pieces are the ones that feel too technical. A set-piece is a complex series of organisms that have to work together. It’s great if you’ve come up with an imaginative set-piece. But if your hero isn’t battling his flaw as well (i.e. Neo fighting Smith in the subway when he didn’t believe in himself yet), then the set-piece feels empty. You might have the coolest location for your set-piece ever, but if you don’t establish big stakes and make those stakes CLEAR, we’re going to be confused about why the set-piece is happening (i.e. the race car set-piece in Iron Man 2).

Learn why the Pod Race, and other set-pieces like it, aren’t working, so that when it comes time to write your own set-piece, you’ll be ready to deliver.

We’re back for Day 3 of Star Wars Week. To find out more, head back to Monday’s review of The Empire Strikes Back.

Genre: Sci-fi/Fantasy

Premise: (from IMDB) Two Jedi knights uncover a wider conflict when they are sent as emissaries to the blockaded planet of Naboo.

About: It is said that Lawrence Kasdan was approached to write the script for The Phantom Menace but that Kasdan felt Empire and Jedi were a step away from Lucas’s vision and believed that Lucas should write and direct the prequels so that they would remain in his voice. Hmmm, that personally sounds like a clever brushoff to me. Other rumors include Frank Darabont and Carrie Fisher being approached to write the script. But in the end, we got George Lucas. Hooray.

Writer: George Lucas

The Phantom Menace is such a poorly told story that as I started compiling the screenwriting mistakes to highlight in this review, I realized there were too many to choose from.

I guess we’ll start at the top. The first problem is the backstory. In the backstory for the original films, rebels were trying to defeat the Empire. It’s simple. It’s powerful. It’s focused. In this movie, we get the taxation of trade routes. In other words, it’s complicated. It’s confusing. It’s unfocused. Now complicated can be good if you have a screenwriter who knows how to navigate complications and who’s dedicated to the extra work required to write something of this magnitude. But George Lucas is neither. He’s openly stated that’s he doesn’t like writing. And since writing even a simple story can take 20-30 drafts to get right, you can only imagine how much effort and how many drafts something complicated would take. And if you’re not committed to all that extra effort, your screenplay’s going to suffer. And this is the main reason the prequels are so bad. Everything here is a first draft idea that was never developed.

Something feels wrong about The Phantom Menace right from the start. We’ve talked about storytelling engines all week and there is an engine here. But unfortunately that engine lacks horsepower. The goal is for two Jedi’s to convince the trade Federation to leave Naboo. In the opening of Star Wars, Darth Vader storms a rebel ship in search of the stolen Death Star plans. In the opening of Empire, Luke Skywalker is kidnapped by a monster and must be rescued. These are both strong and clear engines. Removing a trade blockade from a planet? Borrrrrrrr-ing.

Now to Phantom’s credit, there is one point in the film where things get kind of interesting, and that’s when Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon discover an invasion army. This creates mystery. And it gives our characters purpose. They must now get down to the planet and figure out what’s up. When they get there, they realize the Naboo people are going to be attacked and therefore have to save the Queen. Okay, we actually have a little bit of story going on here. Saving queens is exciting. Right?

Unfortunately, once they escape, they get marooned on Tantooine and things start falling apart quickly. They do actually have a goal on Tantooine, and that’s to get off the planet. But you’ll notice there’s something missing from this sequence that’s been present in every single Star Wars movie up to this point. Urgency. Star Wars added it by making sure the bad guys were always on our tail. Empire did the same, with the Empire always right behind Han. Nothing is chasing them here. We feel like they could be here for months and there would be no consequences.

The thing is, George has a ticking time bomb for the Tantooine sequence – they need to get to the Senate to tell them what’s going on on Naboo before it’s too late. But he doesn’t do a very good job of reminding us of this urgency and the goal itself is so muddled and confusing, that even if he did, we still wouldn’t feel the importance of it. I mean, hasn’t the Trade Federation already taken over Naboo? What does it matter if they get there now or two years from now?

But The Phantom Menace truly dies when our characters arrive on Coruscant (the city planet). This is where I’ll be introducing a new term on Scriptshadow: Scene Of Death.

The Scene Of Death is any scene that exists only to…

a) Convey exposition.

b) Have characters talk to each other about their feelings.

c) Have two people talk about another person.

d) Have two people talk about their views or opinions on things.

Now let me be clear. You can have all of these conversations in your movie. But you have to have them during scenes where the story is being pushed forward. If the only reason the scene exists is to show one of these four things, that scene will draw your story to a complete stop. Now if you’ve had an incredibly intense stretch of really solid storytelling, you can sometimes get away with one of these scenes. But I wouldn’t recommend it. I think there’s always a way to get this stuff in while the story is being pushed forward.

Now your screenplay is in trouble if you write just one of these scenes. But imagine if half the scenes you wrote were scenes of death. Welcome to The Phantom Menace.

This is what happens on Coruscant. The main characters convene in a room and talk about the upcoming discussion they’re going to have with the Senate. Then we go to the Jedi Council where Qui-Gon Jinn says they need to teach Anakin. Then Anakin goes to tell Amidala that he’s saying goodbye. Then we have a boring Senate meeting. Then they go to the Senate committee to ask permission for something. Then Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon Jinn talk. Then Anakin gets tested by the Jedi Council. Then Amidala talks to Jar-Jar about their planet. Then Amidala talks to the Emperor about going back to her planet. Then Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon and Anakin talk to the Jedi Council yet again. Then Qui-Gon Jinn explains what the force is to Anakin. I might nominate this as the worst stretch of scenes in a big-budget movie ever. Out of these 11 scenes, maybe half are scenes of death and the other half so barely move the story forward or are so muddled in their execution, that they destroy any bit of momentum the movie had left. There is no engine underneath this sequence driving the story forward. And there is definitely no GSU. I mean what happened to the storytelling of the first two films?? If somebody wanted something in Star Wars, they went after it themselves. They didn’t go to a Senate committee. Choices George. You have to make interesting choices. Debating anything in a Senate is not an interesting choice.

And the scariest thing? That’s not even the worst part of the screenplay. The worst part of the screenplay is the characters. Even if Lucas had cleaned all this plot stuff up and made each sequence as tight and focused as Star Wars and Empire, it wouldn’t have mattered because we don’t like the characters. Let’s take a look at the six key characters and why they suck.

Qui-Gon Jinn – The mentor character is rarely flashy, but that doesn’t mean he can’t be interesting. I’ll admit that the Obi-Wan Kenobi from the first films wasn’t exactly the coolest character ever. He didn’t do anything outrageous or shocking. But he had this intriguing mystical quality about him and he was very warm. Qui-Gon Jinn is as cold and as boring a character as you’ll find. Part of this is the way Lucas set up the Jedi. He implied in the original films that Jedis were sophisticated and ordered and honorable. Unfortunately, those are all traits that make a character boring. I would probably want Qui-Gon Jinn mentoring me in real life. But I definitely don’t want to put him in my movie if my goal is to entertain people.

Obi-Wan Kenobi – Much like Qui-Gon Jinn, there’s very little going on with Obi-Wan Kenobi. He doesn’t seem to have any character flaws. He listens to and attentively follows everything his mentor tells him to do without argument. And that’s where this dynamic falters. Whenever you pair two people together for an entire movie, you need there to be some sort of unresolved conflict between them. Without conflict, the characters aren’t struggling to find balance. If the relationship is already balanced, then there’s nothing for the characters to fight. That’s going to equal a lot of boring scenes. So you have two characters, both of them with no internal struggles, and no conflict between them. How the hell are you going to make that interesting?

Amidala – Queen Amidala is the worst character in this movie and may be the worst character Lucas has ever created. George tries to create this whole disguise storyline where Queen Amidala disguises herself as a handmaiden. The problem is, there’s absolutely no point to it whatsoever. Had she never disguised herself, absolutely nothing would have changed. This goes back to the use of stakes. If you’re going to disguise someone, ask yourself, what are the stakes to them getting caught? If there are no stakes, then there’s no point in disguising them. If it any point Amidala is discovered when, say, they’re hanging out on Tantooine, what happens? Maybe Qui-Gon Jinn smiles slightly and says, “Wow, you got me.” And that would be it. Look at a movie like Pretty Woman. Watch the scenes where Julia Roberts goes out with Richard Gere to a high-class dinner or a polo match. In those scenes, Roberts is masquerading as one of them. If she gets caught, and somebody realizes that Richard Gere is with a hooker, there are real consequences to that. Maybe the other businessmen don’t deal with Gere. Maybe his reputation takes a shot. Julia Roberts will be humiliated. The fact that George doesn’t realize the importance of stakes in this situation shows how little he understands storytelling.

Anakin – Anakin is a tough character to dissect. Much of our thoughts regarding Anakin have to do with our knowledge of what’s going to happen to him in the future (dramatic irony). Lucas is hoping that just seeing this young happy kid who we know will later become one of the most sinister dictators in the galaxy is going to stir up enough emotions that we’ll be interested in him. And the truth is, Anakin does have some stuff going on. He’s a slave. He ends up having to leave his mother. The seeds are here for a good character. Unfortunately, Lucas really botched the casting. The kid who played Anakin wasn’t a good actor and therefore we just never believed him. I do think that a better casting choice would’ve helped this film tremendously. But it’s also a reminder of a screenwriting tip I’ve mentioned before. It’s probably best not to include a major character under 10 in your script. Finding a good actor who can play a major role at that age is the equivalent of trying to win the lottery.

Jar-Jar – This is going to shock you. Jar-Jar is actually the deepest character in the story. Or I should say, the character whom George Lucas intended to be the deepest. He’s the only character in the group who has a flaw. He doesn’t take life seriously enough. And he doesn’t believe in his worth. That’s what’s led to all of the problems with his people, and why he was ultimately kicked out of the clan. So when you’re talking about unresolved conflict, there’s actually a lot of unresolved conflict going on with this character. Unfortunately, George undercut this with such a goofy annoying character that it didn’t matter. We’re not going to care if a character is able to overcome anything if we don’t like him. So remember, just adding a character flaw isn’t enough. You still have to make that character someone we’ll root for.

Darth Maul – A huge critical mistake that George Lucas made was not including a dominant villain. Not every movie needs a villain. However, if you’re going to write a sci-fi movie, you need a villain. And Lucas actually created a really cool villain here, but ended up portraying him as a nuisance more than a genuine threat to the Republic. The guy barely spoke. He didn’t do anything unless he was told to. He was a weak villain. And if you don’t have someone to point to as the ultimate threat in this kind of movie, then you’re never really scared for the characters. Lucas really should have made Darth Maul a major character with a lot more power. It would’ve helped this movie a lot.

Like I said, I could go on forever with this movie. I didn’t even get to the ending where the bad guys were destroyed by a baffling series of lucky coincidences. I’m just shocked at how much time and effort and money was put into something that was so poorly constructed. If there’s any lesson to come out of this, it’s that this is what happens when you don’t commit to rewriting your script until it’s great. As I struggled to figure out a rating for this film, I realized I couldn’t recall a single moment in the script that worked. For that reason, I have no choice but to give it the lowest rating.

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is why you shouldn’t try and write a complicated multifaceted multi-character epic with politics and secret objectives and dozens of vastly different locations. These are the most difficult movies to write by far. And this is often the result. A bunch of muddled objectives in a muddled plot that’s desperately trying to seem important but none of that importance comes through because it’s all so sloppily executed. To me, The Phantom Menace is an argument for the power of a simple plot. Keep the character goals clear. Keep everybody’s motivations clear. Keep the story goals clear. The first two films were basically bad guys chasing good guys. Even Empire could be boiled down to that. As long as you have that simple structure in place, you can try to find the complications within it. But if you start with an overarching complex story that lacks focus, it’s likely doomed from the get-go.

.

Genre: TV Pilot – 1 Hour Drama

Premise: During the Black Plague, a group of rich Italians head off into the countryside to party out the plague in a beautiful villa.

About: Word on the street is that Bridgerton was so big for Netflix that they wanted more period stuff. Enter Jenji Kohan, creator of Netflix’s famed, “Orange is the New Black.” Let’s just say that Jenji’s version of “fun” is obviously a lot more complex than everybody else’s version of “fun.” Although Jenji is the producer, the creator of the show is Kathleen Jordan, who wrote Teenage Bounty Hunters.

Writer: Kathleen Jordan

Details: 61 pages

Tony Hale will be playing the hapless Panfilo

Tony Hale will be playing the hapless Panfilo

I’m reviewing today’s pilot to remind everyone that Pilot Showdown is coming up!!! Send in your pilot logline along with your title and genre. The best 5 pilot loglines will compete against each other with you, the readers of the site, voting for the best. Whoever wins will get their pilot reviewed the following Friday. There’s obviously an appetite for this because I’ve been getting a lot of pilot loglines sent in. It’s going to be a dandy.

What: TV Pilot Logline Showdown

When: July 21st

Deadline: Thursday, July 20th, 10pm Pacific Time

What: send your title, genre, and logline

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

As the world attempted to decipher why brooding Timothy Chalamant was cast in the role of one of the most charismatic characters in history, I reminisced about when Orange is the New Black first hit Netflix. Along with House of Cards, it felt like a new era in television had emerged, rivaling when Jackie Gleason first appeared on TV.

If you remember, this was the first time in history that an entire season of television shows was offered at once.

It was a strange decision that streamers have, since, backtracked on, at least for their larger shows, as it practically begs people to sign up for a month, binge the new show, then ghost the service.

The practice also inadvertently birthed a new storytelling format – the “movie” TV show. Narratives were now being designed like films, to build over an entire season, as opposed to ebbing and flowing, delivering standalone experiences you could enjoy without having kept up with the series.

My jury’s still out on this format. I don’t think it quite works yet. But writers continue to play with it and learn it. Hopefully, we’ll figure it out because I do like the idea of one long enjoyable narrative.

It’s 1348 in Firenze, Italy. Peasant Licisca is a handmaiden for the worst woman in the world, Filomena, a sort of 1300s version of Paris Hilton. Everything revolves around her. Especially now that her entire family has died from the black plague. Well, except for her dad, but he’s on his way out.

Filomena is visited by a messenger who invites her to Villa Santa at the behest of Leonardo, a really rich bachelor whose plan is to have everyone stay at his villa for one long party until this whole black plague thing goes away.

Filomena ditches her barely alive father, taking Licisca with her, believing she will finally find the husband she so desperately covets. However, along the way, Filomena and Licisca get into a fight that spills out of their carriage and near a bridge where Licisca inadvertently pushes Filomena to her death.

This is when Licisca gets a brilliant idea. Nobody at this place knows what Filomena looks like. So SHE’S going to be Filomena!

Once she gets there, we meet the rest of the crew. There’s the studly doctor, Dioneo, who Licisca immediately crushes on. Dioneo is the doctor for the hapless Panfilo, an ugly dork of a man who can get sick at the drop of a hat. There’s the religious horndog, Neifile, who, unfortunately, married the very gay, Panfilo. Translation: she’s not getting any.

But the biggest surprise is that the two elderly caretakers of the villa, Sirisco and Stratilia, are containing a giant secret. Their master, the owner of the villa, Leonardo, is dead of the black plague. They buried him. If Leonardo is dead, neither of them have masters and they’ll be cast off into homelessness during the worst plague in history. So they must do everything in their power to make sure that their secret never gets out.

What a weird idea.

What a weird FUN idea.

I love a bit of irony in a concept. But the thing with irony is that there are weak versions of it and clever versions of it. This definitely lands on the clever side. One of the things I judge an idea on is how easy it is to come up with. And I’ve never read a single idea that was anything close to this. It’s truly unique. And clever as s—t.

Cause think about it. We’ve seen a bunch of rich people living in these mansions with servants before. That format has been done to death. But this puts an ENTIRELY new spin on it and one that opens up all sorts of fun ideas that the writer takes advantage of.

For example, in what other version of this idea could you kill off the villa owner and everyone just goes along with it? In what other version could your heroine believably take on the persona of a rich noble?

And then you have these interesting relationships. Like this guy who just walks around with his own personal doctor everywhere. As it so happens, the patient is a disgusting rat of a man and the doctor is the most handsome man in the world. So wherever they go, even though he’s the wealthy and important one, everyone falls in love with his doctor.

I think that’s another thing that sets this pilot apart. The writer put a ton of effort not just into the individual characters, but the main relationship that each character had. One with their maid, one with their spouse, one with their doctor, the two caretakers. There are these interesting pairings that lead to a bunch of great dialogue and fun scenarios. It’s almost like teams, which adds a different dynamic when the teams talk to other teams.

I personally think this is going to be too weird for a lot of people. But if you like weird TV and writers that take chances, you’re going to absolutely love this.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Exploit your premise! Identify what’s unique about your premise and make sure there are characters and plot developments that specifically exploit it. This is a show about rich people vacationing in a big villa while waiting out a plague. So the writer killed a character off and had our hero impersonate her. The writer killed off the villa owner, leaving everyone waiting for a guy who’s never going to show up. Most writers wouldn’t have thought that deep. They would’ve got Licisca and Filomena to the villa together. Leonardo would’ve still been alive. The lazy writer thinks in terms of their original idea and not in terms of, “What does a *lived in* version of my idea look like?” The *lived in* version is always dirtier. Things have already happened inside the lived-in version to muddy it up. So make sure to think beyond that very first concept that came into your head.