DIALOGUE WEEK IS HERE! – All this week, I’ve been breaking down dialogue scenes from the movies you love. Monday’s Dialogue Post is here. Tuesday’s post is here. And yesterday’s post is here.

If you want to go to dialogue school, check out Training Day. It’s basically a 120 minute dialogue scene. Which brings us to our first lesson. Don’t focus on writing great individual dialogue scenes. Focus on creating great characters who can then write the dialogue for you. Alonzo is the ultimate dialogue-friendly character. And Jake is the ultimate straight man. Put those characters together and you have dozens of scenes where the dialogue writes itself. Let’s check out their famous first meeting together. For those who haven’t seen the movie, it’s about a young cop’s first training day with a veteran narcotics officer.

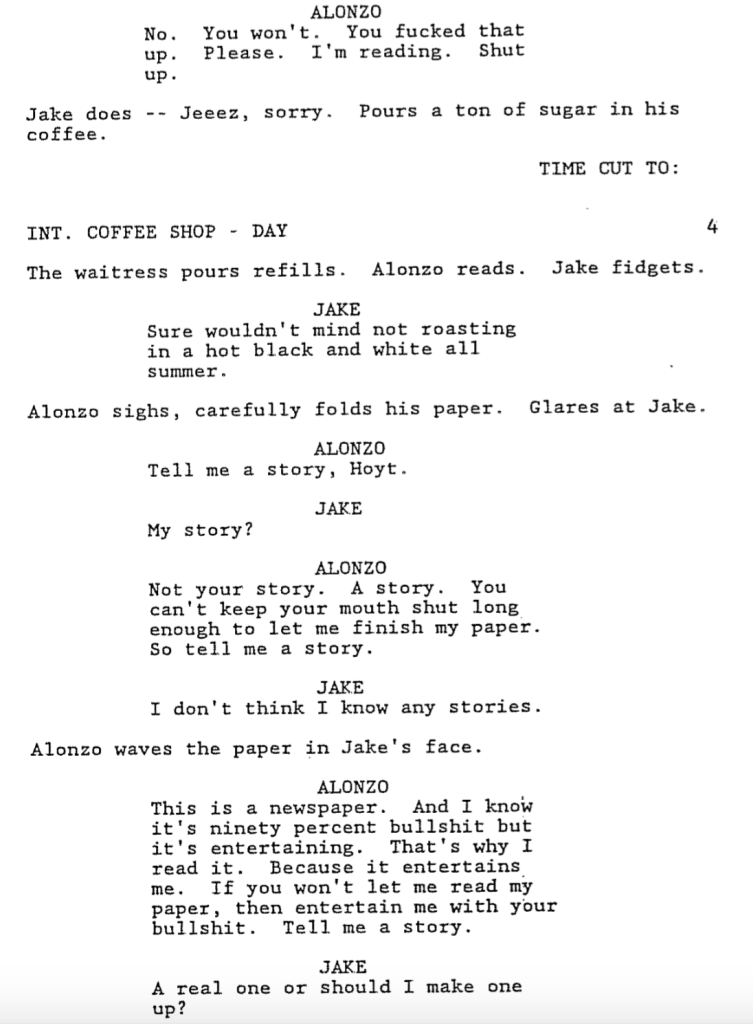

Okay, let’s jump into the easiest way to write a good dialogue scene. Are you ready? Give us one character who doesn’t want to talk and one character who does. That’s it! Boom! You do that, you will write good dialogue. I promise you. And that’s the whole premise of this scene. Jake wants to talk. Alonzo doesn’t.

I could stop there and you’d be halfway towards dialogue mastery. But I want to revisit this week’s theme. Which is that the best dialogue comes from what you’ve done BEOFRE the scene. Not during. We’ve built this entire movie around a dialogue-friendly character in Alonzo. He’s opinionated. He’s brash. He’s colorful. He’s un-p.c. He says the things you’re not supposed to say.

We then placed him across from a straight man. Dialogue-friendly characters work best with straight men. Two dialogue-friendly characters is like having two chefs in the kitchen. With that said, 2 DF characters can work. In Silver Linings Playbook, Pat and Tiffany were both dialogue-friendly and their scenes were great. But generally speaking, the rhythm of good dialogue follows a dominant and submissive pattern.

Which segues nicely into our next topic: power dynamic. Power dynamic is HUGE when it comes to dialogue. The very nature of somebody being “in charge” creates an imbalance. And that’s where the tension is. Tension is conflict. Conflict is drama. Drama is entertainment. In this scene, the power dynamic is obvious. It’s built into their job descriptions. But there’s a power dynamic to every conversation. Yesterday, the power dynamic was with the parents. They were in charge of the conversation. Chris was merely trying not to fuck up. In The Big Lebowski scene, Walter was on top of the power ladder, The Dude was in the middle, and Donny was on the bottom.

In this scene Alonzo’s power is SO MUCH HIGHER than Jake’s that Jake’s walking on eggshells the whole scene, which is what makes the conversation so fun. You can see Jake trying to say something – ANYTHING – to get Alonzo’s approval. If Jake and Alonzo are on the same power level, this scene doesn’t work.

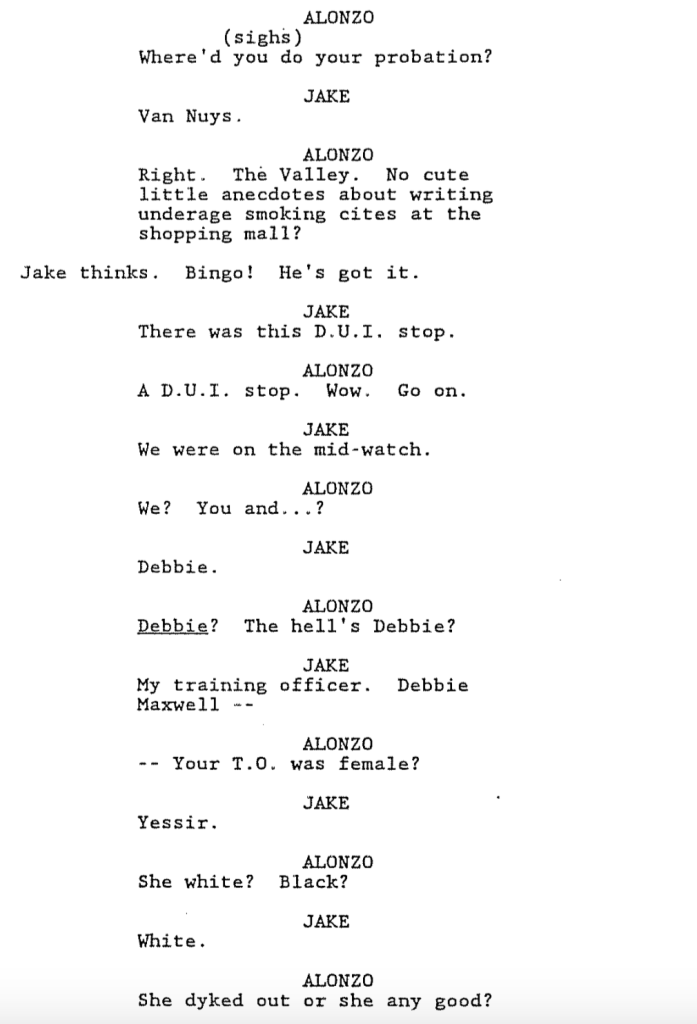

It shouldn’t need to be said that dialogue reveals character. Which means you should be looking for opportunities to tell us about your character through the lines they deliver. Especially early in the screenplay, when we don’t know them yet. It just so happens there are a couple of prominent character revealing lines in this scene.

Alonzo is fed up that Jake won’t stop talking to him, so he demands that Jake tell him a story. Jake mumbles out that he does’t know any stories and Alonzo doubles down. Tell me a fucking story. “A real one or should I make one up?” Jake replies. I love this line because not only is it unexpected. But it reveals how indecisive and eager to please Jake is. I know everything I need to know about this character after this line.

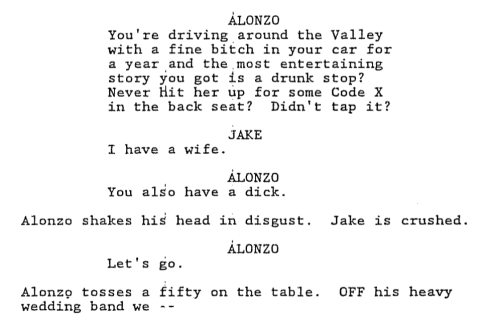

Ditto Alonzo with his response to Jake’s story. Alonzo has no issues with telling Jake that his story sucked (he’s mean). And that getting laid is more important than preventing murder (seriously warped moral compass). In one sentence, we know just how screwed up and ruthless this man is. That’s good writing.

Let’s get into some minutiae. I love how Ayers says that Alonzo never stops looking at his paper during the conversation. It creates this literal barrier for Jake to bang up against for the first half of the scene. A lot of amateur writers assume you need to create the perfect circumstances for a conversation. It’s the opposite. You’re trying to find the angle that creates the most un-ideal circumstances for conversing. By forcing Jake to talk to a wall, it injects one more layer of conflict into a situation that’s already drowning in it.

Another example of this would be two people who meet at a loud club. They can’t hear each other. They have to keep saying, “What??” They misunderstand words, which leads to strange conversation tangents. That’s always going to be more fun than if they meet in a quiet room with no distractions.

I also love this exchange. “Have some chow before we hit the office. Go ahead. It’s my dollar.” “No, thank you, sir. I ate.” “Fine. Don’t.” Alonzo could’ve questioned what’s wrong with Jake here (“Who doesn’t eat at a diner?”). He could’ve challenged him (“You knew you were meeting me for breakfast and you already ate?”). Instead, he uses two words. “Fine. Don’t.” It’s savage. I actually shivered when I read those words. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the fewer words you use, the better. You don’t always have to craft a wonder-line.

Speaking of wonder-lines, there’s one flashy line in this scene. The newspaper line. And that’s appropriate. You shouldn’t be trying to win the lottery with every line. The very act of limiting yourself to one killer line ensures it will stand out. “This is a newspaper. And I know it’s ninety percent bullshit but it’s entertaining. That’s why I read it. Because it entertains me. If you won’t let me read my paper, then entertain me with your bullshit. Tell me a story.”

How do you write a line like this? Because I read a lot of amateur versions of this line. They come out more like, “Now you done fucked up. I can’t focus no more. All because you think you’re more entertaining than a newspaper. So if that’s what you think, then go ahead. Entertain me.” It’s clunky, not as clean. And doesn’t end with the same decisive POP that Ayers line does.

This is a case of a writer paying attention to his environment. You have this newspaper here. It’s already a major part of the scene. Let’s keep using it. But how can we use it to craft a great line? Start by asking questions. “What is a newspaper?” (It’s mostly bullshit) “Why is my character interested in this newspaper?” (it’s his calm before the storm) “What’s in here that he needs so badly?” (nothing really. But it’s one of the few things that entertains him. And since not many things entertain him, he values it).

You now have some PIECES you can use to form a line.

The answers to those questions pretty much form the basis of the first 75% of the line. Ayers then gives the line extra pop at the end by adding some wordplay. Entertainment and bullshit were featured words at the beginning of the line, so he brings them back at the end (“If you won’t let me read my paper, then entertain me with your bullshit”). There’s no science to this stuff but that’s one way of arriving at the line. Of course, for some writers, this stuff just comes naturally. Lucky bastards.

Finally, what I love so much about this scene is that while Denzel got a ton of credit for his performance, the truth is, it’s all there on the page. I don’t see that often. A lot of writers are wishy-washy and it opens the scene up for lots of interpretation. There’s no interpretation here. Any actor reads that beat of Alonzo keeping that newspaper up between him and Jake, and they know exactly who this character is and how to play him.

What I learned: Don’t over-describe pointless actions during heavy dialogue scenes. The less action you write, the more we can focus on what the characters are saying. Ayers writes barely any action here, and when he does, he keeps it to one line, except for a couple of times when it reaches one line and a quarter.

Now that you’ve read the scene, check out the finished product.