For those who haven’t seen it yet, Free Solo is a documentary about a climber, Alex Honnold, who engages in the most difficult and dangerous version of climbing that exists – free solo’ing. This is when you climb mountains without the help of ropes or partners. One mistake and it’s a 2000 foot drop to your death, where you’ll have about 30 seconds to wonder, “Why did I get into this sport again?”

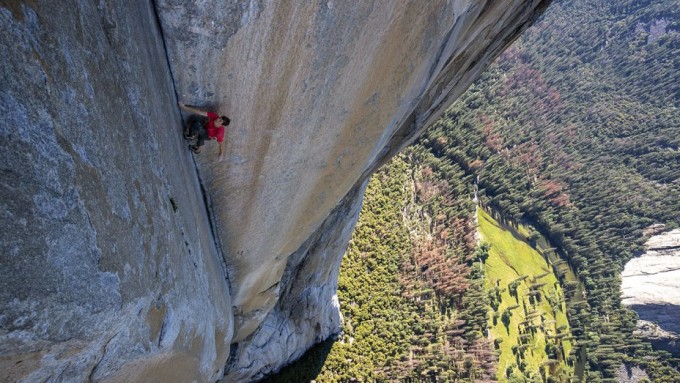

Alex is considered the best free soloer in the world. But despite climbing hundreds of mountains, there’s one he can’t get out of his head – Yosemite’s El Capitan, a sheet of rock that goes straight up for 3000 feet. It is considered the most dangerous free solo ascent in the world. So much so that nobody’s even attempted to climb it. Alex has spent the last eight years gearing up for this climb. This movie documents him finally achieving the feat.

As soon as I finished the movie, I thought of screenwriting. This is one of the best templates for how to write a screenplay I’ve seen in years. That’s because climbing a mountain is the perfect metaphor for the hero’s journey. In the GSU (Goals, Stakes, Urgency) model, climbing the mountain is the story’s “G.”

But what Free Solo reminded me was that it can’t just be any mountain that the hero climbs. Is has to be the most impossible mountain. This film doesn’t work without the phrase, “the most dangerous free solo ascent ever attempted.” You sub in, “one of the harder free solo attempts in the world” and the movie loses its spine. Who cares about conquering a “sort of difficult” mountain?

Free Solo also reminded me just how big of a deal stakes are (the “S” in GSU). We’re always told that the stakes of our hero’s journey must be huge. Well what’s bigger than you slip and you die? I’d say the stakes of this movie are 75% of the reason it’s become a sensation. It just so happens there’s another climbing documentary out right now called The Dawn Wall that follows a climber climbing an impossible wall. The difference? He’s using ropes. He can slip 100 times and it doesn’t matter. Is it a coincidence that Free Solo is blowing that documentary out of the water?

But the great thing about Free Solo is that it doesn’t just explore the outer journey. Like any good screenplay, it focuses on the inner journey as well. Alex has a classic fatal flaw. He’s unable to connect with others. There’s an early scene where he’s dragged to a party and you can see how uncomfortable he is around others. Alex, it turns out, feels best when he’s by himself… when he’s solo.

What do you do once you establish your hero’s flaw? You place something in front of them that challenges that flaw. In this case, Alex gets the first serious girlfriend of his life, Sanni. Throughout the film, Alex talks about how, normally, he doesn’t tell anybody when he’s soloing. He just goes and does it. He isn’t afraid to die because… well, if you die you die. So what? But Sanni throws a wrench into that equation. Now, if Alex dies, he leaves pain and suffering. He emotionally destroys someone who loves him. Alex attempts to dismiss this, saying Sanni will be upset for awhile but eventually find someone else and move on. But when Sanni fights him on this, we get the sense that Alex is saying this to rationalize his solo’ing. If he’s forced to connect with others, it could mean the death of what he loves.

Bringing it back to screenwriting, a battle with one’s flaw creates conflict inside the hero just as compelling as the conflict on that mountain journey. Will Alex back down now that he has someone who cares about him? Or will he continue to put himself first? Continue to ride solo?

This brings up another thing Free Solo does well, which is incorporate Alex’s friends into the movie, all of whom have deep reservations about Alex free soloing El Cap. The director of the movie is one of Alex’s best friends. He’s conflicted about the project because he could be documenting his friend’s death. Alex’s mentor (who, coincidentally, is the star of that other climbing movie I mentioned above) thinks Alex is in over his head with this one. He’d be happy if Alex let it go.

The reason bringing these characters in is important is that they act as emotional multipliers. The more people who care about our hero’s success, the more people we’ll be happy for when the character “wins.” It isn’t just Alex we’re ecstatic for. It’s his girlfriend. It’s his mentor. It’s his best friend. Ironically, we don’t feel that same level of emotion if Alex has no one in his life and does this alone.

As I close this out, you’re probably wondering about Urgency. Free Solo’s got a great G. It’s got an even better S. But what about the U? They focus on urgency a little bit in the film. If Alex doesn’t climb El Cap by the end of the season, it’ll be winter and they’ll have to wait until next year. But the truth is, if you have a goal and stakes that are THIS STRONG, the urgency doesn’t have to be perfect. Especially if you’ve also got a compelling character at the center of the story, which Free Solo does.

If you haven’t seen this film, I recommend it. Let it become the metaphor that drives all of your screenplays moving forward. An impossible mountain to climb where the stakes are sky high.