“Like it Didn’t Love It” refers to an old industry response to the glut of screenplays shoved into the system, and the many people who were required to read them. “What did you think of the script?” a co-worker or boss would ask the reader. “Liked it, didn’t love it.” It was a nice way of saying, “not bad.” Unfortunately, “not bad” doesn’t get a script anywhere. And if we’re being honest, it essentially labels the script dead in the eyes of the company that read it.

As someone who’s read north of 7500 screenplays, I know this experience all too well. The majority of the scripts I read are not good. A select few are very good. Between those extremes is a frustrating selection of screenplays (probably around 15%) that are pleasant reading experiences, but nothing more. I may even enjoy them while reading them. But if literally any distraction comes up, I choose that distraction over the script. These are “Like it Didn’t Love It” scripts. And it’s time to get into how to avoid writing one.

“Like It Didn’t Love It” scripts fall into five categories. The “Technically Perfect” script. The “Safe Concept.” The “Lacks Passion” script. The “Third Draft.” And the “Not Up To the Challenge” screenplay. Let’s take a look at each of these in detail.

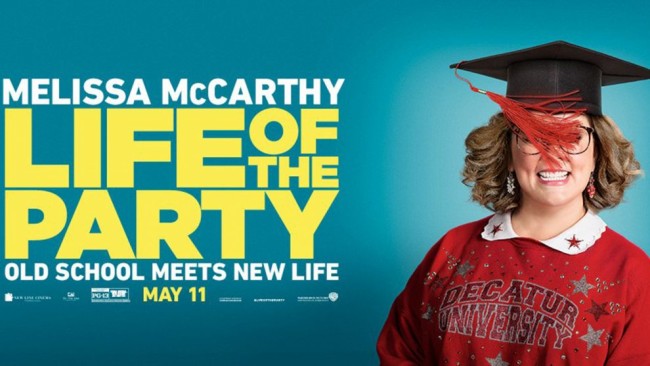

The Technically Perfect Script – The technically perfect script is often written by screenplay-book junkies. They know everything about screenwriting, more than me even. They are slaves to the “rules” of screenwriting, often strangling the creativity from their story in favor of meeting plot beats on the right pages. If a writer’s been at this for a while, they can make a “Technically Perfect” script pretty good. But the ceiling for scripts this devoid of creativity is only so high, which is why even the best ones can only hope to achieve “Like it Didn’t Love it” status. When it comes to recent films, Skyscraper and Life of the Party are “Technically Perfect” scripts.

The Safe Concept – The safe concept has some crossover with The Technically Perfect Script because when you choose a safe generic concept, you will usually execute it in a safe generic way. But the main difference between these two is that the “safe concept” is so vanilla that, even under the best circumstances, the script can only be taken so far. With that said, the word “safe” is used for a reason. It’s “safe” because it works. And that means these scripts, if written well, are mildly enjoyable in the same way that orange chicken from Panda Express is mildly enjoyable. Unfortunately, the reaction to both afterwards is the same. “Why did I put myself through that?” Examples include “I Feel Pretty,” “Truth or Dare,” and “The Commuter.”

The I Clearly Am Not Passionate About This Script Script – These scripts often come about by writers who are sick of their low-concept dramas (or any non-traditional script) being ignored by the industry and finally give in to the notion that you need to write a marketable screenplay to get noticed. They hop on the latest trend (say, Girl With A Gun), writing their version of it, only to get rebuked by the industry once again, reinforcing their belief that their initial approach was the right way to go. — Look, you have to love what you write for it to be any good. Even great screenwriters struggle to make stories work that they’re uninterested in. It’s hard to find produced examples of this, since virtually any lifeless movie could be an example. But yeah, if you’re not getting paid, think long and hard about writing something you have no passion for.

Third Draft Scripts – Third draft scripts are scripts where you can see the promise of the story but the writer hasn’t done the hard work yet. Now, obviously, every writer defines drafts differently. For some, it’s an extensive process that requires tons of outlining and character work each time out. These writers can write a good script in 4-5 drafts. For others, they write quickly, and can belt out a draft in a week. For them, writing a good script takes 10-15 drafts. So “third draft” is more of a symbolic moniker that represents a writer who’s written a decent script that could’ve been a lot better had they written a few more drafts. The example I always give of this is The Sixth Sense. In the third draft of The Sixth Sense, M. Night’s story was about a kid who drew pictures of the future. By the 10th draft, it was about a kid who saw dead people.

Not Up to the Challenge Scripts – “Not Up to the Challenge Scripts” are actually scripts that have the potential to be “Love It” scripts, but the writer’s skill level isn’t yet high enough to stick the landing. Or another way to look at it is that their eyes are bigger than their mouths. These scripts often cover weightier material, a biopic with Oscar in its crosshairs (White Boy Rick) or a time-spanning period piece (Gangs of New York), or really ambitious rule-breaking type projects, a Pulp Fiction or an I, Tonya. You need to have been at this for awhile to pull one of these scripts off. In the meantime, you will be praised for your script’s “flashes of brilliance,” but condemned for its inability to “bring it all together.” While I think it’s important that every writer push their limits, it’s also important to know your limitations. You’re not going to write Pulp Fiction as a beginner. You’re just not.

Now that you know what scripts are most likely to turn into “Like it, Didn’t Love It” scripts, what can you do to write these elusive “Love It” screenplays? There’s no definitive answer to this question. But I will say this. The scripts most likely to make readers fall in love with them are scripts that contain a high level of emotional resonance. A heavy focus is placed on the interplay between character and theme. This is the best combination to emotionally affect the reader. And once you make a reader FEEL something, the chances of them falling in love with your script rise dramatically.

A perfect example of this is Eighth Grade, the film I reviewed on Monday. That was not the most amazing script. It didn’t have much of a plot. But Bo Burnham so effectively explored the theme of loneliness and the desire to connect through this imperfect but impossible not-to-like 13 year old girl, that it didn’t matter. We FELT something. And when you feel something, you don’t care about inciting incidents and first-act turns and whether the “fun and games” section was long enough. Emotion is the great-eraser of logical analysis. Which is why, if you’re trying to become a better screenwriter, the primary area you should be studying is character development. Understanding the psychology of people, then combining that with the technical know-how of establishing flaws in characters (in “Eighth Grade,” it’s that Kayla is too quiet) is the first step towards mastering this skill.

With that said, there are several additional things you can offer that increase the chances of writing a “Love It” script. Number one, take chances in your story. I always say that it isn’t the rules you follow that make your script great. It’s the rules you break. Anybody watch “Swiss Army Man” and think, “Way too many safe choices here?” Two, as I mentioned above, try to write something you’re passionate about. The more passionate you are about something, the more effort you’re going to put into it, and that’s going to come across on the page. Three, if you have a strong voice, like Zoe McCarthy from Tuesday’s review, write a script that takes advantage of that voice. And four, write a “tweener” script. The advantage of tweener scripts (scripts that combine two different genres) is that you’re more likely to write something original. But, of course, everything with a big upside has an equally steep downside. Get these wrong and people ask you, “I couldn’t tell if this was an [x] or [y] film!” A good tweener film is Get Out (horror and social commentary). A bad one is Tag (was it a comedy or a drama?).

I’m sure some of you are asking, “Well, Carson. If some of these Like it Didn’t Love It scripts are getting made, then how bad can it be to write one? Look, Hollywood has too many slots to fill not to make some Like it Didn’t Love It movies. The reality is, however, Hollywood doesn’t look to you, the unknown screenwriter, to provide them with this material. They can come up with average material on their own. As an unknown writer, you must STAND OUT in order to get your scripts through the system. Which is why you should be aiming to write “Love It” material.

I want to finish this off with one final piece of advice. I am not advocating that you write your passion project about the irrigation issues that the native peoples of 1781 New Zealand faced. Every script idea should be seen through the lens of “Will anybody pay to see this?” That’s the caveat to all of this – the one rule you have to follow. Nobody’s going to make your movie if there isn’t an audience for it. Conversely, the bigger the audience potential your idea has, the more lenient the analysis of your script will be.