The Great Gatsby had the best use of 3-D I’ve ever seen. But how many dimensions did the actual storytelling have!?

Genre: Drama/Period

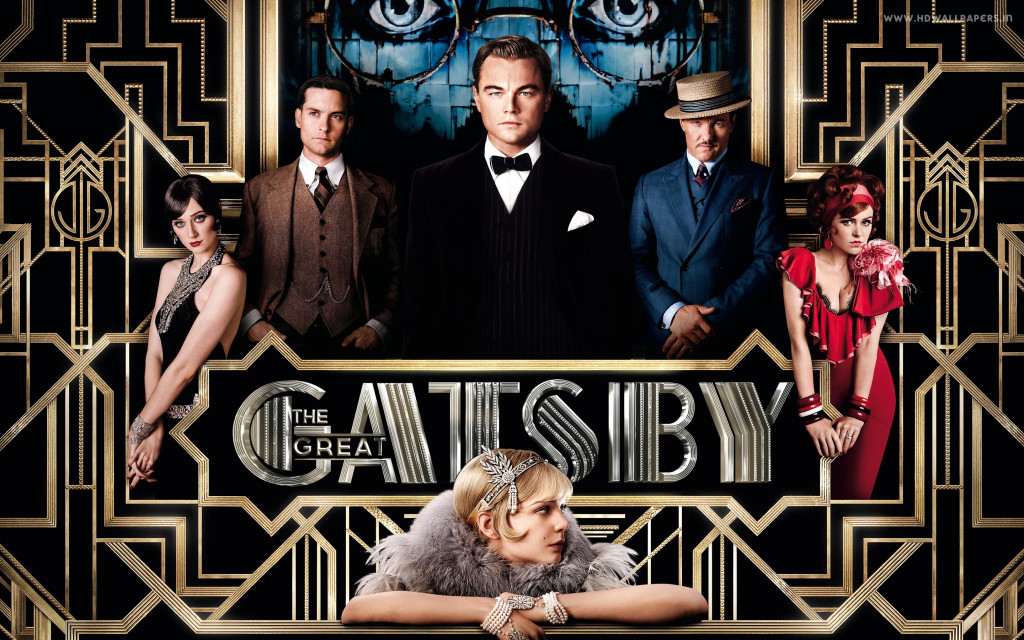

Premise: Set in the 20s, a former writer moves next to one of the wealthiest men in New York. When the man, a shadowy figure known as Jay Gatsby, invites him to one of his famous parties, he finds his life forever turned upside-down.

About: So if the frustration of coming up with a title for your script is beating you down, note that as far back as 1925, writers were still battling the issue. Believe it or not, F. Scott Fitzgerald was set on calling his novel “Trimalchio in West Egg.” It was only after friends convinced him that the title was non-specific and un-pronounceable that he turned to the title we know today. Something tells me had he not made that choice, none of us ever would’ve heard of the novel. Which makes me wonder: How many unknown classics are out there because of bad titles? Speaking of, here’s a little known fact: Gatsby was not a hit when it was first published. It was actually a bomb, leaving Fitzgerald to die believing he was a failure. It was only during World War 2 when schools started using Gatsby in their curriculum that it went on to obtain the status it has today. Baz Lurman and his longtime writing collaborator Craig Pearce adapted the novel for the screen.

Writer: Baz Luhrman and Craig Pearce (based on the novel written by F. Scott Fitzgerald)

Details: 2 hours and 20 minutes long

I love this shit!

A non-comic-book, non-franchise, non-sequel, non-YA-novel-adaptation, non-Johnny-Depp, non-Pixar CHARACTER PIECE comes out in the most competitive part of the year and cleans up 50 million at the box office. Now THAT is encouraging. It makes me believe in the purity of the screenplay again. True, it did have one of the biggest movie stars in the world and the script is an adaptation of a book. But The Great Gatsby is hardly what I’d call a surefire hit. It’s a character study from the 1920s!

Now believe it or not, I’ve read The Great Gatsby. I realized a few years back that there was an off chance I might run into a literary snob at a party who saw screenwriting as an inferior type of storytelling, and this literary jerk-off might corner me with the inquiry, “And what book have YOU read recently, Carson? Or do you even READ books?” In which case I could answer, “Oh, I actually recently read The Great Gatsby. I try to revisit a classic every month or so.” And then I’d triumphantly march off, leaving a bunch of startled partygoers in my wake, amazed at my unending literary know-how. This moment hasn’t happened yet. But it will. Oh trust me – it will.

Now for those of you who ignored your reading assignments in high school or don’t revisit the classics every month like I do, The Great Gatsby is about this guy named Nick Carraway, a writer turned bond trader who moves to Long Island. While Nick is a man of modest means, he seems to have tons of friends who are uproariously rich – like his cousin Daisy, Daisy’s bestie Jordan, and Daisy’s husband Tom (a polo star).

Coincidentally, Nick’s shack is located next to another rich man, Jay Gatsby. Though he holds the biggest parties in town, nobody seems to know who Gatsby is or what he looks like. Well, one day the mysterious Gatsby sends an invitation to Nick to join one of his parties, and despite senators and mayors and celebrities and sports stars attending, Gatsby only seems interested in speaking with Nick.

Fast-forward a bit and we find out that the reason Gatsby is so keen on gaining Nick’s friendship is his secret past with Nick’s cousin, Daisy. It appears the two fell in love many years ago when Gatsby was a poor nobody soldier. The two couldn’t be together because of his lack of wealth, though, so Gatsby went about amassing as much wealth as possible over the last half-decade (most of which came from underground bootlegging) and has come back bigger and richer than everyone in town, all in the hopes of snagging Daisy, a task that’s become tricky seeing as she’s now married. In the end, the lives of all of these rich (and not so rich) folks will collide (literally) in an explosive finale, one in which Daisy will decide who she wants to spend the rest of her life with, Tom or Gatsby.

There is so much screenwriting shit to talk about here, I’m not sure where to begin. Let’s start with this: Gatsby should not have worked as a screen story. It does too many things that should sabotage a narrative, the most egregious of which is having its main character be the least interesting character in the movie. Yes, Nick Carraway doesn’t have jack going on. He’s meager, insular, reactive, boring. The man’s got nothing going on in his life of interest. No intriguing backstory or flaw to talk about. Yet he’s the one taking us through this tale. What’s the deal?

The deal is that he’s a “narrator,” a device that worked quite nicely in the 1925 literary world, but which has since lost its luster. Why? Because at some point someone realized that a narrator who has absolutely nothing to do with anything is probably not main character material. If Gatsby was being written today – ESPECIALLY as a spec – undoubtedly the story would be told through Gatsby’s eyes. This is the man enduring all the interesting shit in the movie. This is the man being active, making things happen. He has the most character development, the most layers. Think about it. He’s the most powerful man in New York, yet the most insecure person you’ll ever meet. He’s draped in the most expensive clothes and vehicles and houses you’ve ever seen, yet he’s unable to see himself as anything other than a penniless nobody. He projects a fantastic life, yet it’s all a lie. He has all this money, but it was all made illegally. It’s no wonder this book has lasted as long as it has. Gatsby is the definition of a fascinating character.

Here’s where the movie ran into trouble though, and I’m not sure if it was entirely the writing or the actors portraying the characters– almost everyone here wilts in the shadow of Gatsby. There’s Nick, of course, who’s only there to offer up exposition. There’s Tom Buchanan (Joel Edgerton) who couldn’t be more of a cliché asshole husband if he tried. And Carrie Mulligan….hmmm, I’m starting to think her time is up. There’s something very…forgettable about her. She has these beautiful sad eyes, which make you want to pick her up and carry her to safety. But she can’t seem to parlay those eyes into any kind of charismatic or memorable performance.

The character who had the most potential within the second string was Jordon, Daisy’s friend, who was always leading Nick around everywhere. However, Fitzgerald created this strange dynamic by which Nick was never allowed too deeply into these characters’ lives, preventing any sort of compelling relationships to occur. Even when the opportunity presented itself, Nick always seemed to pull away from it, as if to say, “Oh, wait, you want me to actually be IN the movie? No, thank you. I’m just going to watch from afar.” It was one giant tease watching him walk around with the flirty Jordan over and over again, only for NOTHING to happen. It almost convinced me that Nick was asexual.

For those interested in discussing structure, Gatsby does offer some talking points. Just the other day we were talking about the “mystery box.” Well, much of Gatsby is driven by the mystery box. The first mystery box is Gatsby himself! What does he look like? Why does he hide in his own parties? Who is this man?? People are constantly talking about him in hushed whispers. There are rumors, guesses, assumptions, all different, all in constant flux.

Once we meet Gatsby, there’s another mystery box (remember – always replace an answered mystery with a new mystery box!). Gatsby seems to want something. We just don’t know what. Eventually, it’s revealed to be Daisy. Finally, there’s one more mystery box, and that is: How did Gatsby accumulate his wealth? This is a big one because the man seems to be one of, if not the richest, men in New York. Everyone wants to know how he became this way.

After all the boxes are opened, the writers realize they need a final force to drive us to the end of the story. Instead of another mystery, however, they choose a goal – for Gatsby to steal Daisy away once and for all, but more specifically, for her to tell Tom that she never loved him. It’s sort of an awkward goal and I’m not quite sure if wanting someone to say a string of words is weighty enough to drive a climax, but it does end up working, as it leads to the most powerful scene in the movie, when Gatsby and Tom battle over Daisy in a steamed up New York apartment.

More importantly, from a screenwriting perspective, there’s something to learn here. You can drive your story forward with a series of mysteries, then insert a late arriving goal to take the story home. Not every movie is going to be Raiders of the Lost Ark, where the goal is established right away. A “late arriving goal” is perfectly fine, as long as you find other ways to keep your readers interested before we get there (in this case, using a series of mystery boxes).

It would behoove me not to mention the amazing use of 3-D here, the best use of it I’ve ever seen. Not so much from a technical standpoint, but from a motivation standpoint. All these other movies seem to use 3-D for the wrong reasons, as a way to make explosions seem more explosion-y. Here, it’s used to bring us back to the early 20th century. I felt like I was inside this world, however exaggerated it may have been. The costumes, the set design, the shots of the cities – it’s all immaculately put together and we’re pulled inside that world, almost to the point where we feel like we could touch it via three dimensions. Add a smashing soundtrack to the mix and this was one of the best pure cinema-going experiences I’ve had in a long time. My only complaint is an over-long second act (did this really need to be 140 minutes long??). But the pure spectacle on display almost made you forget about it.

Script

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Movie

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth watching in the theater for sure!

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A great reminder that many of the most fascinating characters in history are those steeped in irony. Gatsby is powerful but insecure. Successful but a crook. Irony often creates struggle inside a character, and struggle within one’s self is often the most interesting struggle for an audience to watch.