Search Results for: mena

One of the HARDEST things to do in Hollywood is be consistently good. There are so many factors working against making a good movie that very few people in the business are able to do it consistently. It’s why the writer-director of The Sixth Sense can also make The Happening. It’s why the director of American Beauty can also make Jarhead. It’s why the writer-director of the great Jerry Maguire can also give us… Aloha??

Think about all the things that can go wrong. The budget can be slashed in half at the last second. An actor can show up on set and demand a page 1 rewrite of his part. The director can drop out the day before the movie starts. The financing can come in suddenly, forcing you to start your movie before the script is ready. Your romantic leads who had great chemistry in rehearsals, can sleep together and, all of a sudden, the spark is gone. When you think about all of the things that are out of your control in filmmaking, it’s amazing that any good movies get made at all.

Which is why the people who do it consistently deserve attention. There’s a reason why these filmmakers are so obsessively coveted by the studios. Because they’re the only ones you can actually count on. So today, I’m going to give you five of the most consistently successful people in the business, and detail what they’re doing right that you can learn from. Let’s begin with the king of them all… Mr. Spielberg!

STEVEN SPIELBERG

Movies: Raiders of the Lost Ark, Jurassic Park, E.T., the upcoming Ready Player One

Spielberg is the best in the business at recognizing the big idea. But here’s the reason he’s so consistently successful with those big ideas while his imposters consistently fail. Spielberg adds a childlike sense of wonder to his stories, a simplicity of observation that makes them immensely accessible to both kids and adults. You see this even when he doesn’t have a child in the lead role. Spielberg still asks the question, “What kind of cool stuff would a child want to see here?” This formula for success shouldn’t be a surprise. It’s the same formula Pixar uses. Childlike wonder done with a level of sophistication. It’s such a simple approach, you wonder why others can’t replicate it. The reason is that everyone who tries to add that childlike sense of wonder goes too far into juvenile territory (fart jokes, “stepping in doo-doo” jokes – a big reason why The Phantom Menace failed). That turns off the majority of adult audiences, slashing the potential box office in half. The recent “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” is a good example of this approach in action. The childlike sense of wonder is replaced with a juvenile sense of pandering. It’s impossible for an adult to enjoy that movie, leaving the film successful, but a far cry from “Spielberg successful.”

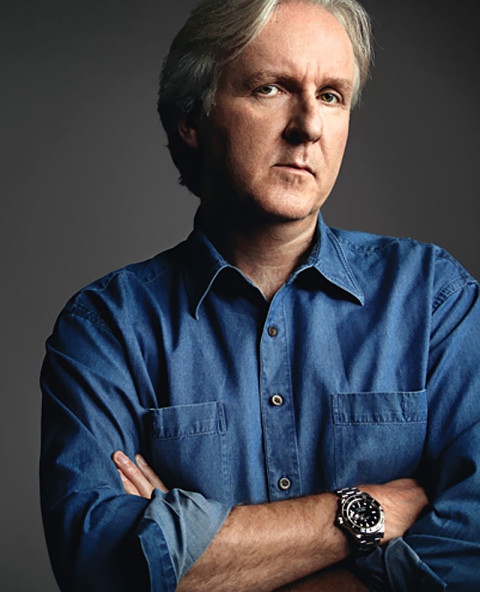

JAMES CAMERON

Movies: Titanic, Aliens, The Terminator, The Abyss, Avatar

Whereas Spielberg appeals to the child in all of us, Cameron appeals to the teenager in all of us. He ramps up the Spielberg “big idea” approach and adds a new ingredient: “attitude.” As much as I love Spielberg, he’ll never direct an action sequence as cool as the LA aquaduct chase in Terminator 2. Speaking of that scene, Cameron is one of the few directors who thrives on pushing the envelope. If you watch most Hollywood movies, it’s directors copying whatever the latest big movie did (remember how many movies did “bullet time” after The Matrix?). Cameron asks himself, “What can I do that’s never been done before?” Just by asking that question, you open your story up to amazing possibilities. A lesser known key to Cameron’s success is his “on-the-nose” approach. Cameron is not afraid to spell it out for audiences (Sarah Conner’s drawn out voice-overs detailing our inevitable demise as a species in Terminator 2, for instance). But while this may annoy frequent cinephiles bored with conventional film, the casual moviegoers who need a little more clarity in their cinematic cereal love it. Here’s the interesting thing though. Film snobs hate every other on-the-nose filmmaker outside of Cameron. How does he manage to escape their wrath? Because there’s no other filmmaker more obsessed with detail than Cameron. The guy fucking spent years inventing alien plant life for his fake world in Avatar. Geeks LOVE that shit. Because details matter. Consider the hack who recently took over the latest Terminator movie. In that film, a key scene from the first movie is recreated. Except the director decided to CHANGE one of the character’s hairstyles (he had a blue Mohawk in the original – not in the new one)!!! It’s this casual attitude towards details that leads to so many forgettable films.

DAVID FINCHER

Movies: The Game, The Social Network, Fight Club, Benjamin Button, Gone Girl

Just like Cameron, Fincher is OBSESSED with details. Except whereas Cameron is obsessed with his worlds and his props and his gadgets, Fincher is obsessed with everything in the frame, from the lighting to the set decoration to the camera angle to the positioning of the actors to the placement of that whiskey bottle on the back mantle that nobody in the audience is ever going to notice. When you watch a David Fincher movie, you’re watching a film from a man who CARES. And that’s not always the case with movies. In addition to this, Fincher has an amazing ability to identify dark populist material. He is, in many ways, the R-Rated Spielberg. One thing that’s separated Fincher as of late is his interest in structurally challenging stories. From Fight Club to Zodiac to Benjamin Button to Gone Girl, these are movies that don’t have that safe straight-forward Act 1, Act 2, Act 3 setup. While I believe you need to learn to tell simple stories first (which is exactly what Fincher did, with movies like Panic Room and The Game), once you have that understanding of traditional structure down, scaring yourself and taking on non-traditional narratives is a great way to stand out.

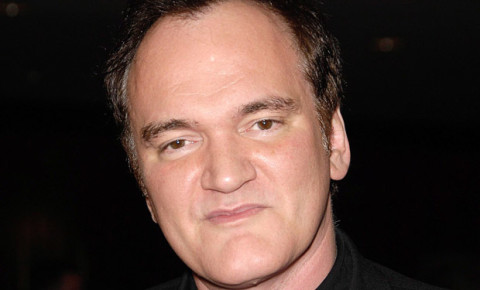

QUENTIN TARANTINO

Movies: Pulp Fiction, Inglorious Basterds, Django Unchained

Tarantino is probably the hardest screenwriter/director to learn from because his style and voice are so unique, if you try to do what he does, you end up looking like a not-as-good version of Quentin Tarantino. With that said, there are a couple of things we can take away from the man. More than any other writer in the business, Tarantino creates strong fascinating memorable characters. Almost every one of his characters is unique in some way, is larger-than-life in some way, and is fun to watch on the screen. In so many scripts I read, writers put little effort into creating characters that stand out. I get the feeling whenever Tarantino sits down to write a character, he asks himself, “How can I make this character memorable?” And he goes from there. A lot of people assume the key to Tarantino’s success is his dialogue. But that’s not true. The reason his dialogue is so good is because he makes his characters so interesting in the first place. If you write interesting characters, they’re going to say interesting things. Which means the dialogue writes itself. This is also why Tarantino can stay in scenes for so long. It’s because of the work he did long before those scenes were written (creating unique interesting characters). So if you want to be like Tarantino, don’t try and write “cool,” or “weird” stuff. Ask yourself for each one of your main characters: “How can I make this character interesting and memorable?” Do this and everything else will fall into place.

CHRISTOPHER NOLAN

Movies: Memento, Inception, The Dark Knight, Interstellar

Nolan doesn’t yet have the pedigree that the rest of the entrants on this list have, but he’s done all right for himself. And there’s one thing Nolan does better than anyone I’ve mentioned so far. He’s not afraid to make you think. Nolan sees the theater as an opportunity to not just entertain an audience, but to challenge them. And unlike a lot of other filmmakers – like David Lynch, like Darren Aronofsky – who likewise enjoy challenging audiences, Nolan is the only one who likes to do so in big high-concept packages. The formula almost seems too obvious. Big ideas that make you think. Why didn’t I think of that? Another thing that Nolan does well is he takes a realistic approach to all of his big ideas. He’s like the anti-Michael Bay in that sense. Whereas other blockbusters (Independence Day, 2012) feel hokey in their approach to physics and logic, leaving the story feeling schlocky and cartoonish, this “realism above all else” approach gives Nolan’s films an additional layer of depth. As crazy as some of the ideas are (dream heists?) you get the feeling that if they were introduced into the real world? This is how they would go down.

My big takeaway from these five titans? Come up with a big concept. Treat it with a childlike sense of wonder or realistic plausibility, whichever you think will work better for your particular idea. Challenge yourself to create larger-than-life memorable characters. Push yourself into narrative areas that make you a little afraid. And above all, pay attention to the details. Now go write that million dollar spec!

Note: FOUR MONTHS LEFT UNTIL THE SCRIPTSHADOW 250 DEADLINE!!!

So over the past few weeks, I’ve had some discussions with writers gearing up to write their next screenplay. Some of these were new writers with only a few screenplays under their belt. Others have been trying to break in for 10+ years. The discussions universally gravitated towards, what’s wrong? Why haven’t my screenplays sold or gotten me an agent, or even gotten my best friend to read them?

95% of the time it comes down to that the concept isn’t any good. And the fascinating thing I’ve found over time is that the writer actually knows this. They’ll actually say to me, “I know that the concept isn’t very good but this isn’t about the concept. This is about the characters and their journey they go through and blah blah blah…”

Hold up, hold up, wait a minute, hold on.

What did you just say?

Did you really just say you knew the concept wasn’t any good? And you still wrote the script?? Believe it or not, this answer is so pervasive in the amateur writing ranks, that I don’t know why it still surprises me. The only explanation I can come up with for why they do it is that they believe they’re different in some way. That they’re special. And the rules don’t apply to them.

Unfortunately, that’s not how this business works. This business IS a concept-driven business. Not only because the script has no chance of getting made unless the concept is good. But because Hollywood is a numbers game. Everyone says no to everything – EVEN GOOD CONCEPTS. A yes only comes along every once in awhile. Therefore, you have to spread the widest net and get the most reads in order to get that yes. If you have a lame (or boring, or uninspired) concept, you’re not going to get the number of reads necessary for the odds to pay off. A good concept gets 50, 100, 200 times the number of reads a boring concept does. Imagine how much better your chances are of breaking in with those kinds of odds.

So how can we ensure we have a good concept? Aren’t those hard to come up with? I mean, if it were easy, everyone would be doing it, right? Well, before we get to how to write a good concept, let’s start with how to avoid writing a bad one.

A new phrase I want you to add to your screenwriting vocabulary is: “The Potential of Boring.” If your idea sounds like it has the potential to be boring, don’t write it. This is not to be confused with the script itself. The script (or the movie) may in fact be the greatest movie ever. But if it SOUNDS like it has the potential to be boring, don’t write it. Because, chances are, nobody’s going to read it. One of my favorite movies of the last two years is Philomena. I loved it. I would never, in a million years, however, allow an amateur writer to write that spec. Why? Because it’s about an old woman who goes searching for her son. The average person hears that and they think, “That has a strong potential to be boring.” Ideas that sound like they have the potential to be boring will not get read.

Another good way to know if you’ve got a boring concept is to play the elevator game. Pretend you’re stuck in an elevator with a Hollywood producer and he asks you to pitch your movie. Go, do it right now. Pitch your movie to Imaginary Producer in Elevator Guy. It should become clear very quickly whether you have a good concept on your hands. If you’re sitting there going, “… and she goes on this road trip of self-discovery and meets this guy. And he’s a drug-addict and then she remembers that what really brought her happiness was her poetry so she starts writing poetry, going from town to town, performing on the street…” That script’s not going to get read. “A young family excited to start their life together finds the perfect home, only for the college’s biggest fraternity to move in next door.” That’s going to get you a read.

As far as how to come up with a good concept, there isn’t any one way. There are clever ideas (like Neighbors, which I just noted), there are ironic ideas (like The King’s Speech, about a man who can’t speak who must give the most important speech in history), but if you’re still stuck trying to find that big idea, start by thinking “LARGER THAN LIFE.” Focus on a scenario that’s bigger than what happens in your everyday life. Going to pick up groceries then coming home to have a fight with your wife isn’t a movie idea. Going to pick up groceries, coming home to find your wife spread out on the floor dead, and the cops think you did it so you have to go on the run. That’s a movie idea. But I’m going to take this one step further. The larger than life your idea is, the more likely it is that it’s a movie idea. The Hunger Games, Guardians of the Galaxy, Captain America, The Hobbit, Transformers, Maleficent, X-Men, Big Hero 6. These ideas take place in different worlds, different universes in some cases. They’re larger than everything.

Let’s see how this can be applied to a basic idea. Say you want to write a movie about sex. So you write about normal people obsessed with sex. The movie is called Nymphomaniac. It makes 10 dollars at the box office. Why? Because there’s no “larger than life” angle to it. In comes Fifty Shades of Grey, currently the highest grossing movie of the year. Let’s now make one of the characters a billionaire. How many billionaires do you know in your everyday life? I’m guessing none. This aspect gives it a “larger than life” feel.

That might not be the best example, you can always skew the numbers in your favor when making these arguments, and there will always be exceptions to the rule. But I’m telling you. By and far, over the last 30 years of this business, this is the formula that wins out for writers trying to break into the industry.

Now there’s one writer I was talking to in particular who had been writing for about seven years. He was a good writer too, and he was frustrated that he still hadn’t broken in. I pointed out to him that none of his scripts really satisfied the “larger than life” criteria. There were a few you could argue were close. But like I said, the MORE larger than life it is, the better your chances are. And he tended to keep his stories more grounded, more based in reality. Which is exactly what he said to me. “But Carson, what if I just don’t like to write those kinds of movies?”

And I realized that some people just want to write about real human conflict, real human drama, without all the hoopla of a flashy concept. They’re more interested in reality. To these people I would start off by saying, “Understand that by taking that stance, you’re making your chances of success infinitely harder.” Once you’ve accepted that, we can go to the next piece of advice. And the next piece of advice would be this: “Stop bullshitting yourself.” It is completely possible to write a human drama wrapped inside a big concept. I’ll give you an example.

A couple of years ago, a writer broke through with one of the hottest scripts in town. It was called “Maggie,” and it was about a young girl who was turning into a zombie. Except in this take on the mythology, it took six months to turn into a zombie. I thought the script was okay, but that’s not the point. The writer was a genius. He wanted to write a story about cancer. But if he wrote a story about cancer, he knew no one would read it (keep in mind, this was before Fault in our Stars). So he placed the allegory inside of a marketable genre that made the story more high-concept. He told it as a zombie tale. And just like that, the concept is larger than life.

You can explore the human condition inside of ANY idea. So don’t fool yourself into thinking you have to write about a small town family who struggles to make ends meet after the dad loses his job in order to explore people. There was a script on the Black List a couple of years ago that did a wonderful job exploring a family amidst an alien invasion. Guess which one of those scripts is getting read? And they’re both doing the same thing – exploring the human condition. It’s just that one writer was smarter – he gave his story a wrapper that would make people interested. Hopefully, you can learn from him.

Genre: Drama

Premise: An ex-Death Row worker who has since isolated himself from the world finds his life reinvigorated by the arrival of a beautiful teenage girl.

About: A lot of people chastise the Black List for celebrating scripts that already have production deals or writers who already have established careers. But baby scribe Anthony Ragnone truly is an “out of nowhere” find. Outside of some assistant work, he was just your average amateur writer trying to get noticed. He did so with “Huntsville,” which finished around the middle of the pack on the 2014 Black List. (Note: Due to some reveals in the screenplay, I would suggest you find and read this script before reading the review. A lot of people should have the script to pass around since it was on the Black List)

Writer: Anthony Ragnone II

Details: 92 pages

If I heard that a band of eager young screenwriters were heading to Los Angeles and would be here tomorrow, and the city commissioner gave me one billboard to put up at the entrance of the city, in which I could offer any message I wanted to said screenwriters to give them the best chance at success, I know exactly what that billboard would say:

SIMPLIFY YOUR SCREENPLAY!

One of the most common mistakes I see new writers make – and it only seems to be getting worse – is biting off more than they can chew. An extremely complicated plotline following multiple protagonists with flashbacks and flashforwards where every third character’s motivations are shrouded in mystery… It certainly sounds fun from an eager young writer’s point of view. But the amount of skill required to pull something like this off is higher than you could possibly know.

And I know that sucks to hear because when you’re a young writer, you want to break the rules. You want to show why you’re different. So you conjure up some part-Charlie Kaufman, part-Aaron Sorkin, part-Scorsese screenplay that is simply too complicated to wrangle into any sort of enjoyable shape.

The scripts that I see which continue to sell or make an impression on the industry are often simple stories with a slight complication or two. If you look at the latest Black List, Catherine the Great (the number one script) is a very simple story following a woman who rises to power. The only complication is that it doesn’t take place in one continuous timeline. My favorite script on the Black List so far, The Founder, is even simpler. An ambitious man tries to create a fast food empire. There are no bells and whistles. Just the necessary conflict he endures while trying to achieve his goal.

The Brian Duffield script, The Babysitter, which finished 3rd on the list, follows a kid with a crazy baby sitter. The Wall, which finished sixth on the list, is about a one-on-one battle between two snipers. Achingly simple. The first script on the list that I would categorize as “complex” would be “Mena,” which uses an overly complicated 40 page montage before it gets into its core story. Not surprisingly, I think it’s the weakest of the scripts mentioned. Reading it was a struggle.

This brings us to today’s Black List script, which is, yet again, a simple story. It’s about a 40 year old man, Hank, who lives a boring isolated life. His job is to watch the local high school parking lot so that aspiring Ferris Buellers don’t try to play hooky. For fun, he occasionally goes fishing at a local lake. Other than that, he takes care of his turtles, and enjoys a drink or two.

Everything would’ve continued on this way had Josie not arrived. A smoking hot punky 17 year old, Josie isn’t who she seems at first. She’s actually thoughtful, sweet, and cool. She pushes Hank to open up, get out of his comfort zone, and actually go out and have fun. Within a few days, the two are practically best friends.

And that’s when Marcus gets involved. Marcus is one of those kids who would ditch school every day if it wasn’t for Hank sitting in that parking lot busting him every time he sneaks out of school. Marcus hates Hank, and that makes things very awkward when Marcus starts dating Josie.

Josie jumps back and forth between spending time with the two, and you get the sense that something here is going to break. It’s just a question of who snaps first. Of course, if that’s all there was to the story, there wouldn’t much to talk about. There’s something in Hank’s past that he doesn’t like to talk about, and it may be the thing that undoes them all.

Once again, we’ve got a super simple story here. A friendship between two unlikely people that’s thrown into disarray by a dangerous third party. The reason that simple stories are so effective is because it’s easy for the reader to understand what’s going on. And that’s a powerful tool as a writer. Once someone thinks they know what’s going on, you can mess with them. You can throw unexpected twists and turns at the story. You can build suspense. You can foreshadow standoffs between characters.

When everything is shrouded in mystery and hiding behind fifteen cross-cutting storylines or time jumps, the most effective storytelling tools become unavailable to you. It’s hard to be suspenseful if we’re not even sure who’s who or what’s what.

Huntsville uses a very simple device to keep our interest, and that’s an impending sense of doom. You usually only hear about this device in relation to horror scripts. But it can be used in any genre, and if you’re writing a slow-burn story, it’s pretty much a necessity. The impending sense of doom here is Marcus. He’s our bad guy who doesn’t like Hank. And the closer Hank gets to Josie, a girl he’s falling for, the more we get the sense that, at some point, Marcus is going to get rid of Hank.

Another reason I think writers are scared to keep things simple is because they equate simple with boring. To these writers, I’d say shift your complexities away from plot and into character. If you can create at least one complex character, readers will keep reading if only to try and figure them out.

What makes Hank such a good character are all these hints at his dark past. Every once in awhile, Hank will see a man sitting in his apartment, long gray oily beard in an orange jumpsuit, just staring at him. Part of the reason we keep reading is we want to know who this man is and how he relates to Hank.

But also, we want to know how far Hank will go. He knows he can’t and shouldn’t be with this girl. It’s illegal. And yet, this is the only person in the last ten years who’s reached out to him, who’s shown him that there’s still joy in life. I’ve said this before but whenever you have a character who’s fighting something within themselves, you, at the very least, have a watchable character.

(Spoilers) I’ll finish this off by saying I did NOT see this ending coming at all. It takes a lot to fool me since I’ve seen every trick in the book. But Ragnone got me good. No doubt, the ending is what got this script on the Black List. And I’ll go so far as to say it never would’ve worked had the rest of the story not been so simple.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s a difference between a simple story and a simple concept. A simple story is just telling a story in a simple way, and is often preferred. A simple concept is another thing entirely. As much as I liked this script, I’m not sure I’d advise other writers to write a concept this simplistic (older guy meets younger girl and becomes friends with her). Unless you find an agent who sends it to everyone in town and it gets on the Black List, scripts like this more often fall through the cracks. I’d advise a high concept or a genre approach if you’re trying to get noticed as an unknown writer.

Genre: TV Pilot – 1 hour Comedy

Premise: When the Devil gets bored with the goings-on of Hell, he decides to pack up, head to Los Angeles, and open a bar. What he never expected was to start caring about the people in the city.

About: Born in New York, Tom Kapinos moved to Los Angeles in the mid 1990s, got a job as a reader at CAA, and parlayed that into a script sale that got Jennifer Aniston attached. The movie was never made, but the spec was read by the Dawson’s Creek folks, where Kapinos soon became one of the writers. After the show was over, Kapinos fell into the Tinsletown Purgatory but five years later emerged with the hit show, Californication, on Showtime. Kapinos has now, smartly, jumped onto the comic book bandwagon, taking the DC character, Lucifer, and turning it into a TV show which will debut on Fox, probably as a companion to Gotham.

Writer: Tom Kapinos

Details: 55 pages

Okay, so I’ve just started Season 3 of House of Cards, and I’m worried. For those planning on watching the show in the future, avert your eyes, I’m about to get into spoilers. Basically, when you have a particular goal driving a TV show, the show will encounter a crossroads when the protagonist achieves that goal. Frank Underwood’s (Kevin Spacey) goal has always been to become president. That’s why we watched for the first two seasons – to see if he could do it. Now that he’s done it, where does the story go?

Now there are a million new story challenges you can create for the president of the United States. But no matter what you do, it’s hard to recapture the excitement of the underdog trying to become the top dog. I’m worried that the show will start focusing on plot (We must improve our relations with Russia!) as opposed to character, which is what makes all TV shows, and this one in particular, so good. Whatever the case, I’m eager to see how they solve this problem. It could lead to either some really good or some really bad screenwriting. I’m sure those who have already seen Season 3 will offer up their thoughts in the comments. I only ask that they do so without spoilers.

How does this tie into today’s pilot? Well, Frank Underwood is a morally corrupt individual. He will do whatever it takes to get what he wants. It’s become apparent to me that these types of characters are great for TV shows. Someone who’s a little bad is so much more entertaining than someone who’s pure good. And today, we have a character who’s probably about as bad as they get. The devil himself. Let’s take a look at Fox’s upcoming show… Lucifer.

When we meet Lucifer Morningstar, he’s been chilling in LA for a good year, running his hot nightclub, Lux, and basically doing whatever naughty thoughts come into his head. The reason Lucifer has so much fun is that he’s devoid of that part of the body that actually cares about things – what is it called again? – oh yeah, the heart.

That’s about to change, though. One of Lucifer’s pet projects has been Delilah, a talented musician who debuted at his club and who has since become one of the biggest musicians in the world. However, like a lot of musicians, she makes terrible dating mistakes, and on this particular night at Lux, one of those mistakes drives by the club and guns her down.

What starts as anger eventually becomes sadness in Lucifer – a feeling he’s totally unfamiliar with. It bothers him enough that he insists on joining local hot but uptight cop, Chloe, on her investigation into the murder. Chloe doesn’t like the candid and sexist Lucifer, but she’s amazed by his Jedi-like power to get anybody to tell him what he wants to know.

The two go from Record Company owners to rap stars to movie stars as they trace Delilah’s sordid relationship past, before finally discovering that the wife of one of Delilah’s lovers got her bodyguard to do the hit. It’s a satisfying conclusion for Lucifer, who can now go back to his debauchery-laden ways. Except there’s one problem. He actually finds himself caring for this Chloe woman. Humph. Why does the real world have to be so complicated??

Let’s start off today talking about Investigation Simplicity Syndrome. 50% of the TV shows out there revolve around some kind of procedural format. Characters go on an investigation, usually to find a murderer. It’s a tried and true format where the goal and stakes are built right there into the genre.

But Investigation Simplicity Syndrome can destroy a procedural. This occurs when the investigation is too simplistic. Here Lucifer and Chloe go to a record producer, who says he didn’t do it and offers, “It was probably that rapper.” They go to the rapper, who says, “It was probably that movie star.” They go the movie star and, after talking to his wife, realize she was the one who did it.

It was so basic as to seem purposefully boring. Now when you’re writing a comedy series, which Lucifer basically is, you get a little more leeway in this area. If people are laughing, they’re not demanding Fargo-like complexity in their plot. But you have to put a LITTLE effort into the investigation.

Another problem with Lucifer is Lucifer’s key power – his ability to get people to tell him the truth. It makes things too easy! Characters throw the answers at him without any effort on his part: “Oh yeah, you should go check out that guy. He’s suspicious.” With any movie or show, you want to make things DIFFICULT on your characters – not simple – because then your characters have to struggle, and characters who struggle are always more fun to watch than characters who are handed everything.

So the combination of Investigation Simplicity Syndrome and Lucifer being handed all the information without having to work for it made for an incredibly boring investigation.

Which means I probably hated Lucifer, right? Not exactly. What Lucifer lacks in plotting it makes up for in fun. Lucifer is a funny character, throwing out punchlines faster than Mayweather throws punches (when an Angel visits his club: “Amenadude! How’s it hanging, big guy? Didn’t you see the sign?” “No angels allowed?” No? Hmm, maybe we should be using a bigger font.”)

And let’s not forget the wish-fulfillment, one of the more underrated components of character creation. We all wish we could do bad things and not have to suffer the consequences for them. That’s what’s so fun about watching Lucifer. He’s bad and he doesn’t give a shit.

That alone wouldn’t have been enough though. Kapinos smartly realizes that every good TV character needs somewhere to go. If there’s nothing they’re struggling with, then they’re basically a robot. So what’s hinted at, here, is Lucifer’s growing introduction to feelings – something he never had to deal with down in Hell. Once a character must deal with consequences, their choices become a lot more difficult, and we sense that’s going to be Lucifer’s journey as a character.

The script also benefits from Protagonist Dramatic Irony. This is when we know something about the character that nobody in the story does. This typically works best with serial killer protagonist flicks (American Psycho), but here, it’s simply that Lucifer is the devil. Therefore, whenever someone challenges Lucifer, or gets in his face, or gives him trouble, our superior knowledge allows us to delight in what’s about to follow. This happens several times in the script, such as when Scrip9 (the rapper) tries to intimidate Lucifer, only to end up on the floor crying like a baby when the conversation is over.

So what Lucifer lacks in plot, it makes up for in character. And for this reason, I give the pilot a passing grade. This is television, and in television, character is king. So if you nail that, you get some slack on the plot front. Still, if Kapinos thinks this show is going to last with investigations like this, Lucifer’s going to be buying property back in Hell before sweeps week. I hope that doesn’t happen because this series has potential.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: An easy way to avoid Investigation Simplicity Syndrome is to add COMPLICATIONS to the investigation. Just look for places to make things more difficult for your investigators. They go to their next lead – but the lead turns out to be dead. They go to their top suspect, but a lawyer opens the door and says his client won’t be talking to them. The chief of police tells them to stop investigating – the case is closed. It can be anything, as long as it throws the investigation off its typical path.

So, I hope all of you experienced lots of sexy time this Valentine’s Day weekend. Or at least ate a lot of chocolate that fell down and partially melted on your sad protruding shirtless belly while you watched the Lord of the Rings trilogy for the 30the time. Either way, I’m sure you’re confused about this weekend’s box office.

Yes, I’m talking about 50 Shades of What The Hell Just Happened and its 81 million dollar domestic haul. Now we all knew the movie was going to do well, but 81 million dollars is the yearly GNP of Cuba. And 50 Shades of Grey means something completely different over there.

Ever since this book became a phenomenon, I’ve been trying to figure it out. I mean, there are movies I cringe at but whose success I still understand. For example, I’ve never sported round black glasses, worn a cape, and rambled off the spell, “Gizzlestorm lazzle-trousers!” yet I know why Harry Potter is a phenomenon. It’s a deeply rich and imaginative world with a very well thought out story.

I tried to read 50 Shades, got halfway through the second chapter, and thought, “This has got to be the worst writing ever.” What is the appeal here? Women are smart. Aren’t they? Why are they buying this garbage? Sure, everyone’s fascinated by sex, but if all you had to do to make 80 million dollars was throw sex into your movie, I’m pretty sure every studio in town would be doing so.

Why, for instance, did that old movie Secretary, starring Maggie Gylenhaal, and covering basically the same subject matter, make 1/40th of this movie’s opening weekend haul? Where was the ravenous female audience then?

I’m tempted to toss this into the “Who the hell knows?” pile but as screenwriters, it’s essential to pay attention to and understand the box office. You want to know what genres are doing well. You want to know what subject matter is doing well. If something bombs, you want to know why. It something becomes a hit, you want to know why.

And that’s not to say you should follow trends. I think it’s fine to follow trends at the beginning of the trend (say as a movie that everyone knows is going to do well approaches its opening weekend). But if there’s been 7 fantasy movies over the last two years, writing another one probably isn’t going to go over well. Even if you’re a Level 20 Elfen.

But I’m still curious to hear your thoughts about 50 shake-and-bakes. Is it pure wish-fulfillment? Is that all it takes to write a hit book/film? Could we do the same for men? Write a movie about a bunch of guys who bang girls with no strings attached? If someone wrote that, would it really make money? Actually, Entourage is coming out soon so we’ll see.

Moving over to a similar topic, I finally finally finally saw Boyhood this weekend. I love Richard Linklater. I like the Before Sunset movies. Slacker was a game-changer. Dazed and Confused is still a classic. But this film had gimmick written on it since it was first announced 15 years ago. Now to its credit, it was probably the most beautiful earnest gimmick in the history of gimmick cinema. But it was still a gimmick.

One of the indisputable strengths of the Hollywood film is its ability to suspend your disbelief. If you start your movie following a six year old boy, and then cut to ten years later where he’s now 16, but played by a different actor, nobody in the audience is going to say, “Oh man, those weren’t the same actors! It was so fake! They were different people! Faaaaake!” Different actors playing the parts of the same character through time is one of easiest things for an audience to buy into.

So why in the world would you film a movie over 15 years to mask something that doesn’t need masking? That people already buy into? UNLESS. Unless you want the making of the movie to be a part of the movie itself. And if you’re doing that, you’re achieving the exact opposite of what you set out to do – which is to suspend people’s disbelief. Cause now all they’re thinking about is the real life person playing the part.

Another irony is that once you take away the unique process of making of this movie, there isn’t a whole lot going on. It’s a kid growing up. And, sure, there’s a naturalism to it that you can argue draws you closer to the experience. But to me, all my fears going in were realized. This was a once-in-a-lifetime Frankenstein-esque experiment and I admire Linklater for trying something different. I just honestly think you could’ve made this exact same movie in four weeks. You wouldn’t get the same publicity you’re getting now for filming over 15 years. But the film itself would be the exact same.

Finally, some of you have written in wanting me to discuss the Oscar screenwriting nominations. The Oscars have always been an interesting topic because I’m not sure the people voting for the winner always know what they’re talking about.

What I’ve found is that, in the case of Adapted Screenplay, the nod usually goes to the script dealing with the most intense social or political issue, regardless of it’s the best script or not. So last year, 12 Years a Slave won when Philomena was a far better screenplay. But one was about slavery and the other an old woman looking for her child. The year before Argo won when, I think, Silver Linings was the better script. In 2009, Precious won when I think Up in the Air was the better screenplay.

On the original screenplay end, the Academy tends to favor scripts that are the most different, regardless of the quality of the script itself. And I think that’s because people in this industry genuinely respect anyone who’s able create something unique inside a business model designed to churn out the exact opposite. So last year, the one-sided romance “Her” won, even though I think both American Hustle and Blue Jasmine were better screenplays. Django Unchained rightfully won the year before that, as it hit that sweet spot of being both different AND the best screenplay of the pack. The year before that, Woody Allen’s weird time-travel film, Midnight in Paris, won, which was likewise a deserving spot.

This year, Birdman is favored, mainly for that same reason. Now do I think Birdman deserves to win the Oscar this year? I think by this point you all know what my feelings are about the Birdman script. I thought it was awful. And I think the only screenplay it’s better than in the nominations is Boyhood. Foxcatcher, The Grand Budapest Hotel, and Nightcrawler are all far better scripts that show real skill and understanding as far as how to write. Birdman is like a wonky fever dream and that doesn’t demonstrate skill in my eyes. But if the Academy votes the way it has been voting, it looks like Birdman will win.

With that in mind, here are the nominations for best original and adapted screenplays and my thoughts on each:

Best Original Screenplay Nominations

Birdman – Zaniness without form. Commendable for its chance-taking, but that’s the only thing it has going for it.

Boyhood – I’m not sure I’d even consider this a screenplay. It’s more like a documentary. Having said that, it’s easily the most unique writing experience of the five entries, as Linklater had to keep rewriting the script over many years to include what was going on in the world. Not sure how that will favor into voters’ minds, nor do I know if they’re even aware of this. In the end though, it’s too simple of a story to win any awards.

Foxcatcher – This has the second best character of all the entries, in Steve Carrel’s John Du Pont. It’s a very understated screenplay but a master class in below-the-surface tension. It’s not all “LOOK AT ME!” like Birdman, which is one of the reasons I liked it so much.

The Grand Budapest Hotel – It’s hard to judge Wes Anderson on his writing alone, since his directing is inexorably linked to everything he puts on the page. While I don’t think this is his best work, this is the best mythology he’s created yet.

Nightcrawler – This is the screenplay that deserves the Oscar hands down. It’s got the best character by far. It moves like lightning. The structure is perfect. The dialogue is top-notch. It doesn’t have the same buzz as Birdman because the directing is so much better in that film. But as a pure screenplay, this crushes Birdman.

Best Adapted Screenplay Nominations

American Sniper – The fact that this is even in the running for an Oscar is a joke. It’s a very boring screenplay highlighted by a fairly interesting character. I hope the Academy isn’t fooled by this film’s mega-success. As words on the page, this is very average screenwriting at best.

The Imitation Game – If the Academy knows what they’re doing, this is the script that should win. It not only has a great central character, but the way it jumped back and forth in time and made a subject matter interesting without the benefit of expanding into the larger picture of the war (at least in the script – we don’t see the war happening) – that’s real skill there.

Inherent Vice – I’ll be honest, I haven’t seen this. But I hear it’s a complete mess. We live in a world where Paul Thomas Anderson gets a screenwriting nomination whenever he makes a film so this is probably taking up the slot of a more deserving screenplay.

The Theory of Everything – I haven’t seen this either so I can’t comment on it. But let’s be honest. The only chance this had at winning is if Stephen Hawking had died before the voting started.

Whiplash – I’m happy that the Academy nominated such a small movie. I don’t love Damien Chazelle as a writer, but this script does have some good things going for it, particularly the character of drum instructor, Terence Fletcher. It goes to show that if you write one lights-out memorable character in your screenplay, your script is going to get some heat.

So which scripts weren’t included but should’ve been? I don’t think there’s any question that Gone Girl should’ve been in there. The Fault in Our Stars may have been teen fare, but it was a really good script. I don’t know about the movie, but St. Vincent was a great script. That’s one of the weird things that hamper this competition. A good script can be screwed up by a first-time director or a bad casting choice, which means a lot of the best scripts go unrecognized. And I think Chef should’ve been in there as well.

Then again, that’s what’s so fun about analyzing this stuff. Everybody has their own opinions. What do you guys think? Which scripts should win it all this year?