With Valentine’s Day only 24 hours away, it’s only natural that we review a script about LOVE…. and killing.

Genre: Rom-Com/Action

Premise: (from Black List) After Liv, a world-class hitwoman, breaks up with her boyfriend, Martin, he puts out a massive contract on his own life to get her attention. What Martin doesn’t realize is that it’s an open contract with a 48-hour expiration, so now every assassin in the western hemisphere is coming after him. Liv makes a deal to keep him safe until the contract expires, if he pays her out the full bounty. With the clock ticking, the two must elude some of the world’s most prolific killers.

About: This finished Top 20 on last year’s Black List. The writer has one credit, which was pretty recent! Copshop!

Writer: Kurt McLeod

Details: 111 pages

Florence Pugh in a fun role for once?

Florence Pugh in a fun role for once?

It may not seem like it sometimes. But we here at Scriptshadow support LOVE.

TayTay and Travis? They’re like two giant halves of a heart in my eyes.

And so today, just 24 hours before the loviest day of love on the calendar, I present to you this Black List rom-com.

29 year old Martin is a software engineer who can count the amount of times he’s had sex on two hands. Not people, mind you. But ACTUAL TIMES. To put it mildly, Martin is not suave with da ladies.

MARTIN’S DATING PROFILE

PHOTO [harsh lighting, unflattering angle, same smile]

OCCUPATION: Software programmer, self-employed

LIKES: Romantic comedies, good wine, picnics in the park, spa days, quality time with family and friends

DISLIKES: Toxic masculinity, conspicuous consumption, heights, enclosed spaces, public swimming pools

LOOKING FOR: That perfect someone to spend the rest of my life with…

But due to a dating app screw-up, Martin has somehow been matched with the drop-dead gorgeous Lex. Lex does not hold back her disappointment when she arrives at the restaurant date, looking at Martin and saying, “Wait, who the f&%$ are you?”

LEX’S DATING PROFILE

PHOTO [sexy silhouette, sunglasses, bangs hiding pouty face]

OCCUPATION: work

LIKES: no

DISLIKES: yes

LOOKING FOR: no strings

For some reason (aka, because the writer needed a movie) Lex kind of likes Martin. So she sleeps with him that night and then starts sleeping with him on the regular. However, after several months, she ghosts him. And soon after is when we learn that Lex is a big game hitwoman. Which partially explains why she keeps her relationships short and surface-level.

Cut to a year later and Lex is following up a gigantic score – 2 million bucks. The reason it’s so big is because it’s an open target. Any assassin can collect. But when she gets to the target, she finds out it’s Martin, who’s been doing some development and looks a lot better. Martin says that he bought the contract on himself cause he’s since learned about her job and realized this was the only way to see her again.

Due to some complicated financials and a hit-man loophole, Lex concludes that she’ll make more money off the hit if she waits until it’s called off (or something). So she still plans to kill Martin. But, in the meantime, she has to help him evade all the other hitmen trying to kill him. However, when her handler, Francis, realizes she’s trying to game the system, she puts a separate hit out on Lex. So now Lex and Martin are running for their lives and, quite possibly, falling in love.

Let me start off by saying I’m noticing a trend in a lot of the scripts I’ve been reading.

Which is: THE FIRST SCENE (OR SEQUENCE) IS THE BEST SCENE IN THE ENTIRE SCRIPT.

The scene where Lex shows up for this date with Martin and Martin bumbles through it is really funny. Nothing ever quite reaches the perfect balance of awkwardness and humor as this date.

Writing a great scene is hard. So kudos if you can achieve it at any point in your script. But if your first scene is your best scene, that means that the reading experience gets worse the further through your script the reader gets. Which is not what you want.

So why does this happen?

Writers want to show off the coolness of their concept right away. So they come up with an early scene that sells their concept. Also, the earlier you are in your script, the less dependent you are on the plot, which hasn’t locked you into any scenes yet. So you have more freedom to play around and have fun.

But you can’t allow that to be the best scene in your script. You just can’t.

When you write a great scene early, consider that THE BAR. And then, every subsequent major scene, try to clear that bar. If you can’t honestly say that your later scenes are better than that first scene, rewrite them.

This all comes down to laziness. Lazy writers start strong then fizzle out. Strong writers start strong then keep getting better. Yes, it will require more effort on your part. But embrace that challenge! Don’t be Mr. Lazy Pants.

Especially if you’re allowing your alter ego, Movie Logic A-Hole, to do your writing.

Movie Logic A-Hole is your lazy alter-ego. If it were up to him, he wouldn’t do any outlining, he wouldn’t do any research, when he ran into a script problem he wouldn’t try to figure it out. Instead, Movie Logic A-Hole barrels through the script regardless of whether what he’s writing makes real-world sense or not. As long as it makes “movie logic” sense, that’s all that matters to him.

Love!

Love!

Movie Logic A-Hole makes a big appearance in today’s script, destroying any legitimate chance the script has of working. This entire movie is based on the idea that a man who’s trying to get his assassin girlfriend back puts a 2 million dollar blanket hit out on himself. Let me reiterate that. A man knowingly pays money to have every major hitman in the world try to kill him in the hopes that his hit-woman ex-girlfriend will get to him first and he can try to get back together with her.

Movie Logic A-Hole is very persuasive. When Real World Writer says to him, “But no one would ever really do that,” Movie Logic A-Hole replies, “Chillllll dude. It’s a commmeddy. Comedies are funny. They don’t have to make sense.” When Real World Writer says to him, “But how could he know that another hitman wouldn’t find him first and kill him?” Movie Logic A-Hole replies, “Because she’s like, the best. She would get to him before any other hitman.” When Real World Writer says, “But how would he know that she was the best? I’m not sure you can go on a guess when you’re putting your life on the line.” Movie Logic A-Hole replies, “You’re thinking way too deep, man. Nobody cares about that stuff when they’re watching a movie.”

While it’s true that audiences never think of the word “logic,” when watching a movie, they do know when something feels off. If they sense that the storytelling is lazy, they stop being engaged. That’s the primary effect of movie-logic. If you use it enough, your story takes on a general feeling of laziness.

If you want to see how this looks in practice, go watch “Lift” on Netflix. Notice how quickly you stop caring about what’s happening. That’s because many of the creative choices (especially the sequence that opens the movie) reek of movie logic. It feels LAZY.

With that said, there is room for Movie Logic A-Hole to be involved in your screenwriting journey. Especially in comedy, where, if you have to make a choice between funny or logic, you pick ‘funny.’ BUT ONLY OUTSIDE THE MAIN PILLARS OF YOUR PLOT. You don’t want to hammer movie-logic nails into the pillars of your story. Those pillars need to be as logically strong as possible. This entire movie rests on the idea that a guy would put a contract on his life in the hopes that his hitwoman ex-girlfriend will get to him before the other killers. That’s the aspect of the story that needs to be the most convincing. Yet it’s the least convincing.

Save your movie logic for stupid stuff like a killer has your heroes trapped in the back of an alley and then a crazed cat leaps out of nowhere onto the killer’s head, allowing them to get away. I’d prefer you *not* write this scene. But if you’re going to use movie logic, that’s where you want to use it – on stuff that isn’t directly tied to major plot points.

The most dangerous thing about Movie Logic A-Hole is that he’s super convincing. Especially late at night. Especially deep into a writing session. Especially when a deadline is coming up and you’re running out of time. Movie Logic A-Hole starts whispering all types of nonsense in your ear and, unfortunately, he’s persuasive.

So watch out for him. Because he’s the difference between a solid well-constructed story and a messy weak one.

Ever since pure rom-coms became excommunicato, these “rom-coms with an edge” took their place. So I wouldn’t be surprised if this became a movie. It would make for a fun trailer. But the script wasn’t for me. Does this mean love loses?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Okay, let’s take a look at the disastrous logline the Black List included…

After Liv, a world-class hitwoman, breaks up with her boyfriend, Martin, he puts out a massive contract on his own life to get her attention. What Martin doesn’t realize is that it’s an open contract with a 48-hour expiration, so now every assassin in the western hemisphere is coming after him. Liv makes a deal to keep him safe until the contract expires, if he pays her out the full bounty. With the clock ticking, the two must elude some of the world’s most prolific killers.

That is more of a mini-summary than it is a logline. With loglines, it’s about conveying the concept, the main character, the goal, and the major source of conflict. You should aim for 30 words or less. With that in mind, we get my rewrite…

After his hitwoman girlfriend ghosts him, a lovesick introvert takes out a 2 million dollar contract on himself in the hopes of luring her back into his life.

I do basic logline analysis for $25. E-mail me if you want to get your logline in shape! carsonreeves1@gmail.com

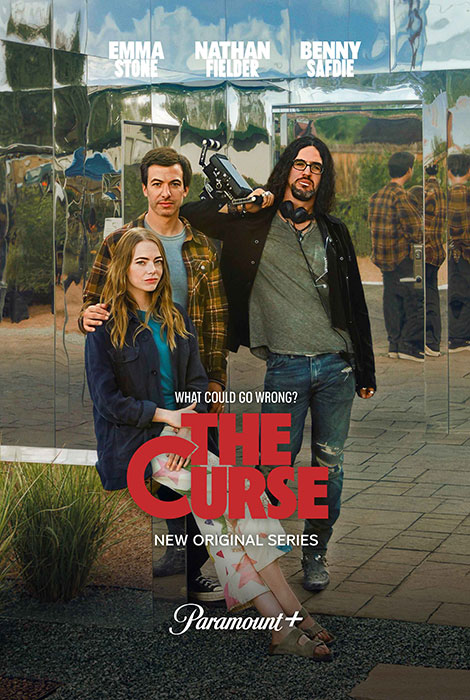

A couple of weeks ago, I saw a Christopher Nolan interview where he said that Ben Safdie and Nathan Fielder’s show, “The Curse” had no comp in television history. It was *that* unique. Combine this with an overall frustration in how bad television has been lately and I was seriously considering giving The Curse a chance. Why was I resistant to do so in the first place? Let’s check the tape, shall we? That is correct. I gave The Curse the lowest rating a Scriptshadow-reviewed pilot can get. A “what the hell did I just read?”

So, what happened between then and now? How did The Curse become the first TV season I finished in over a year? Let’s find out.

If you have no idea what The Curse is, let me pitch the entire package to you. Benny Safdie is one half of the best new directing team since the Coen Brothers entered the filmmaking scene. Bennie and his brother, Josh, made two of my favorite indie movies of the past decade, Good Time and Uncut Gems (Adam Sandler).

The directing duo were primed to take over Hollywood when Benny Safdie started pursuing an acting career. He was in the Obi-Wan show as well as Nolan’s Oppenheimer. His brother, Josh, started to get annoyed. And, just like that, the two canceled their next film together.

Benny befriended comedian Nathan Fielder, who is the king of awkwardness. His comedy is all about things being awkward and uncomfortable to watch. They came up with this idea when a homeless person said to them, “I curse you.” That sparked them to wonder, “What if that curse were real?”

They then did what everybody in Hollywood does when they have a new project – they go to the A-List. Everybody asks the A-List if they’ll do their movie (or show). And 999 times out of 1000, the A-Lister says no. But, to their shock, Emma Stone said yes. And all of sudden, they had a buzzy project on their hands.

The concept of the show is kind of complex so hang with me. A husband (Asher) and wife (Whitney) are making one of those HGTV shows. Whitney, whose parents are millionaire slum lords, is trying to erase the mark her parents have left on the world by doing the opposite of them.

Using their money, she buys out a lot of real estate land in a poor remote California community in order to build “passive energy” houses. Passive energy means that the house uses no energy whatsoever. It has zero imprint on the planet.

Whitney is determined to use the local Native American community to bless these homes and decorate them, particularly with local Native American art. All Whitney cares about is being good to the community and making up for the horrors that white people have put others through over the centuries.

Don’t worry. This show is not woke. It’s actually making fun of woke people. Whitney is a parody. In reality, she doesn’t care about these people at all. She cares about the way it makes her feel to “right” these “wrongs.” It’s purely selfish, although she’s not self-aware enough to realize this.

Asher, meanwhile is the beta “nice-guy” husband who, deep down, understands that his wife has gone way too far with all of this. But he’s so infatuated with her and holds her up on such a high pedestal, that he just goes along with all of it. He thinks, as long as I do what she says, she’ll stay with me.

Benny Safdie (Dougie) plays their showrunner. Dougie is destroyed by a fatal drunk driving accident he was involved in years ago. This has made him unable to fully cope with the world. He’s also kinda weird and acts odd at times. But, in the end, he just wants this job to keep going so he can get paid.

The “curse” part happens in the first episode. Asher gives a little homeless girl money for the show (so it can be captured on camera). He then takes it back after the camera stops filming, and that’s when the little girl looks him deep in the eyes and says, “I curse you.” This makes its way into the story because when things start falling apart for Whitney and Asher, he wonders if it’s because they’ve been cursed.

So, why did I change my tune on my “What The Hell Did I Just Read” rating?

Just like Christopher Nolan said, this is unlike anything you’ve watched before. And for someone like me, who’s watched everything, that’s exciting. Cause boy do Safdie and Fielder push the limits of subverting expectations.

I’ve never seen a show or a movie where the writers will purposefully set something up to deliberately not pay it off. I see bad writers do this all the time. But the reason they don’t pay their setups off is because they’re either too lazy or forgot about it.

Safdie and Fielder do it for a different reason: To ensure that the viewer has NO IDEA what’s coming next. They want you twisted and turned and upside-down so that they are always in control of how the story arrives in your brain.

Even casual TV watchers will be 30 minutes ahead of an average episode of television these days. They’ve seen too much TV. So they know where you’re going.

But that never happens here.

One of these setups is Dougie’s drug-driving backstory. In order to make sure he doesn’t drive drunk again, Dougie always carries a digital breathalyzer in his glove compartment. We see him, time and time again, take the breathalyzer out while he’s driving, blow on it, and then check the results – which usually come back close, but never over, the limit.

Safdie and Fielder will then spend an inordinate amount of time in the car, in silence, with Dougie driving at night, and we just KNOW that a car crash is coming. Cause it has to come, right? We get so many setup scenes to let us know it’s coming.

But it never does.

That singular subplot is the poster child of how this show works. We, the viewer, are being yanked around and played with. We can’t figure out where the story is going so we stop trying.

Another thing this show does a bang-up job of is scene-writing. When I tell you guys how important scene-writing is, the point I’m always trying to make is that a scene should be able to entertain you on its own. It shouldn’t just be a vessel to set up later plot elements.

Every scene here is entertaining on its own. And not in the way you’d expect. Safdie and Fielder do this unique thing where they try to create the most awkward situation and then make you sit in it.

Not for a few seconds. But a few minutes. They really sit you down and don’t let you escape the second-hand embarrassment, the awkwardness, the frustration you have for the characters on screen. Almost every scene is built like this and I’m not sure I’ve ever seen it before. It’s so unique that it’s almost like its own language.

For example, there are multiple scenes where Whitney, who’s just an awkward person in general, is desperately trying to befriend Cara, a local young Native American artist. Whitney wants Cara to be the face of the art in her renovation of this community.

But Cara sees Whitney for who she is. She’s a fake. She’s pretending to care. But all she really cares about is feeling good about herself. So Cara is having a hard time signing the rights away to her art so it can be on the show. She keeps putting off signing that waiver. The problem is, 70% of the show has already been shot and Cara’s art is everywhere. So Whitney really needs her to sign that waiver.

We then get this scene where Whitney comes over to Cara’s to pin her down and finally get the signature. Whitney is avoiding being pushy because she wants to be friends with Cara (as well as not ‘exploit’ her as a white person). Cara is trying to be cordial as she continually changes the subject whenever the request to sign the waiver is made.

Safdie and Fielder WILL NOT LET YOU OUT of this totally uncomfortable dance between these two. They sit in the awkwardness way longer than you’re comfortable with and, by the end, you’re crawling out of your skin.

There are 4-5 of those scenes in EVERY episode. These guys are brilliant at it.

Now, you may have heard some rumblings about the final episode of The Curse and its “WTF” climax. I’m not going to spoil it for anyone. But, keeping in line with what I said earlier – it is impossible to predict. I tried to predict it. But I was nowhere close. That, alone, is reason to celebrate this show. When have you ever watched anything where you could take 50 guesses at what will happen in the final episode and not come close with any of them? I don’t think that’s ever happened before.

With that said, this is still not in the same league as White Lotus. The writing does get loosey-goosey at times due to the fact that the narrative and writing-style are so odd. But the good stuff still outweighs the weak stuff by a wide margin.

I don’t know if I would recommend this to a casual viewer – like a family member. But I recommend it to everybody who reads this site because it teaches writers how to stay ahead of the reader. It teaches you how to make offbeat choices. It teaches you to always question whether you’re being too obvious the moment a major plot beat comes up. And it teaches you how to write characters into very uncomfortable situations. It does this last part better than any movie or show in history.

Be sure to let me know what you think once you’ve watched it. :)

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the watch

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

Week 6 of the “2 scripts in 2024” Challenge

If you haven’t been present on the site lately, here’s the deal. I’m guiding you through the process of writing an entire feature screenplay. Then, in June, we’re going to have a Mega Screenplay Showdown. The best 10 loglines, then the first ten pages of the top 5 of those loglines, will be in play as they compete for the top prize. So far, I’ve helped you choose a concept, sculpt your outline, and build your characters. Last week, we wrote our first ten pages. Here are the links if you’re late to the party…

Week 1 – Concept

Week 2 – Solidifying Your Concept

Week 3 – Building Your Characters

Week 4 – Outlining

Week 5 – The First 10 Pages

One of the things I baked into this challenge was making this ACHIEVABLE. I mean, all you need is one hour a day. Who doesn’t have that? So, if everything is going according to plan, you should have ten pages written by now. Two pages (aka one scene) for five days a week, with two extra days in the week to catch up, make adjustments, or rewrite.

Now that we’re headed into our second ten pages of the script, that means we’re hitting one of the most important beats of the entire script. I’m talking about the inciting incident.

The inciting incident is built out of this idea that, before the crazy stuff starts happening in your story, we have to get to know your character. We have to see them in their “normal” habitat. The reason we want to see them in their normal habitat is so we have something to contrast them against when they’re thrown on this big journey.

In that sense, the inciting incident (which typically occurs between pages 12-15) is a divider. It divides the past life (pages 1-14) from the future life (pages 16-110). My favorite way to think of this “divider” is the event that causes the “problem.” The problem is the thing that your hero must now deal with for the rest of the movie. The problem also creates the goal because the act of solving any problem is a goal. If I wrote a story about a guy whose car broke down on the way to a date with the girl of his dreams, the car breaking down is the event, which creates the problem (I no longer have a car to get to the date anymore), which creates the goal: do whatever needs to be done to get to the date.

One of my favorite examples of an inciting incident is War of the Worlds. In that movie, we see Tom Cruise’s everyday life as a construction worker and a family man and then BOOM, the event is sprung on us. And boy is it a good one. Alien tripods come out of the ground and start killing everyone! This creates a problem: Tom’s family (half of it) is in danger. Which creates the goal: Reunite with family.

Like all classic story beats, inciting incidents work best when you’re using the Hero’s Journey. The Hero’s Journey is when a character is content (but unknowingly unhappy) living a mundane life. And then: BAM! Something happens to shake them out of that existence, sending them off on a life-changing journey.

But inciting incidents can be tricky when they don’t fall under the classic Hero’s Journey template. That’s when I hear writers complain and say, “These forced plot beats are restrictive and ruin the art of creation! They are evil, Carson! Eviilllll!” Watch, you’ll see some commenters make that argument down below.

Look, no one’s saying you have to use an inciting incident. But it’s such an organic part of every story, it makes your story better 99% of the time. Think about it. If you told a friend about your day, you’ll include an inciting incident without even thinking about it. “I was at work, minding my own business. Then Sara comes up to me and says I’m responsible for our biggest client canceling their order.” Sara coming up and saying you screwed up the order IS THE INCITING INCIDENT of your story.

But yes, it’s true that some scripts don’t allow for organic inciting incidents. Take yesterday’s script for example: Neobiota. In that story, Melanie’s “normal life” occurred before the script even began. The inciting incident, technically, is the plane crash that placed her in this position. That created the problem that our hero had to solve.

But Mikael actually did something clever here. He made the “life in her normal habitat” section of the script her life on the beach after the crash. We spend 10 pages of her getting acclimated to her new surroundings before we introduce a new problem, aka the inciting incident: one of the dead passengers stands up and starts moving.

Another movie that has a non-traditional use of the inciting incident is Star Wars. In that script, we don’t even MEET the main character until 15 pages in. That’s when we start Luke Skywalker’s “normal life.” The inciting incident doesn’t come for another 15 minutes when Luke’s aunt and uncle are killed. This motivates Luke to head off on this journey to save the galaxy.

What’s interesting about Star Wars is that it has an earlier inciting incident as well. But, in order to understand it, you must understand that the first fifteen minutes of the movie has a different protagonist: Darth Vader. Yes, Darth Vader is the “protagonist” of the first segment of the movie. The reason he’s the “protagonist” is because he’s the one with the goal: Recapture the stolen Death Star plans.

That’s why he barges into the ship. He needs those plans! The inciting incident for Darth Vader’s story, then, is R2-D2 escaping in a pod and heading down to nearby planet, Tattooine. This is the “problem” that gives Darth Vader his goal: Retrieve that droid. Some people might even call this the “actual” inciting incident of the movie as it happens near the traditional “inciting incident” point (12-15 pages in). But the real inciting incident is what motivates your *real* protagonist, which is why Luke’s aunt and uncle being murdered is the more accurate representation.

A lot of people get the inciting incident mixed up with the break into the second act (pages 25-30) and it’s understandable why. Once your inciting incident happens, your hero should technically be thrust on their journey, which is where the second act begins. But what’s supposed to happen in the traditional Hero’s Journey is that your hero feels safe in his world. He likes his world. Then this inciting incident comes around, creating a problem he must solve. But guess what? He doesn’t want to solve it. Solving it requires going off into this new strange scary world that he doesn’t want to go into. So what does he do? HE RESISTS. That’s what the space between the inciting incident and the beginning of the second act is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be the section where the character resists.

The reason this resistance matters is because it conveys something important to the audience: that your hero has a weakness. Their refusal to change conveys that they have growing to do. If the problem occurred and the hero was just like, “Yeah, let’s go! Woohoo!” Then your hero is already internally strong, which isn’t as interesting. The resistance shows that growth is required. And growth is the whole point of a journey.

Another reason why the resistance after the inciting incident is important is because it’s similar to real life. In real life, nobody wants to change. We’re all resistant to it. So when we see our hero resist, we relate to that. This is a key reason why stories work so well. When our hero finally does take on the journey and ultimately change, it’s a reminder that we can change too! So it invigorates us, gives us hope, sends us back out into life with a pep in our step.

Now, as some of you might’ve caught onto, certain scenarios don’t lend themselves to this. Take War of the Worlds. The attack of the Tripods is so intense and in your face that you don’t have the opportunity to sit around and resist. “Hmmm, I don’t know if I want to go on this journey. It’s too difficult.” No, the journey has come to you! You have to go on it!

But you can still create resistance in how your hero reacts. A hero only truly goes on a journey when they take action. So you can create that resistance by having Tom Cruise run away a lot, hide, resist. Then, when he realizes he has to save his freaking family, he takes action and you’re thrust into your second act.

Star Wars had its own issue with the resistance period. It had used its first fifteen minutes on a bunch of characters other than its hero. So when Luke experiences his inciting incident of his aunt and uncle dying, we’re already 30 minutes into the movie. We don’t have time to dilly-dally so Luke takes a beat then says, “I’m ready. I want to go on this journey.” And off they go.

Now, Lucas and his writing crew did a sly job here because they incorporated an earlier scene after Luke and Obi-Wan escape the sand people where Obi-Wan tells him, “You need to help me out.” And Luke resists then. He says, “Nope.” So that resistance was retroactively built into him in a way where he could say “I’m ready” the second his aunt and uncle are murdered. That’s important to note. Each inciting incident has its own potential issues. It’s up to you to figure out how to solve them.

Some of you may want to say that the real inciting incident in Star Wars is Leia’s message to Obi-Wan Kenobi but it isn’t. That message is not meant for our hero. It’s meant for Obi-Wan. Let me make this clear. The official inciting incident is the thing that sends YOUR HERO (not any of the supporting characters) out on their journey.

By the way, this is why important plot beats such as the inciting incident get complicated in big ensemble pieces (Star Wars movies, Avengers, Fast and Furious). In those movies, each character has their own journey, which forces you to motivate all of them. In some cases, this requires you to create a bunch of mini-inciting incidents, like Star Wars does. A lot of writers will solve this problem by treating the group as one character (Avengers). Give us a Thanos trying to destroy the world and everyone’s problem and subsequent goal is the same.

Also, with Avengers, or serial killer movies with detectives, or Indiana Jones, you often don’t have that resistance period because the problem is their job. Indiana Jones doesn’t resist because his freaking job is to find ancient antiquities. The Avengers don’t resist because they’re superheroes and saving the world is their job. Same with detectives and cops. When they get a new case, they don’t usually resist (although in some situations they will and I actually find those stories to be better because of that) because it’s their job.

The main thing to remember here for these next ten pages is that you want to introduce a big problem in your hero’s life and then, if it fits your story, show them resisting it afterward. A character journey is almost always more powerful if they, at first, don’t want to go on it. This shows the audience that they’re not yet ready and that change is needed. That way, later on, in your third act, when they finally are ready to change, it will be more powerful. This is why they say that if you have a problem in your third act, it’s usually because there’s a problem in your first act. Not properly showing that resistance could very well be that problem.

Friday = write 1 scene

Saturday = write 1 scene

Sunday = write 1 scene (you should be near your inciting incident here)

Monday = write 1 scene (should be an inciting incident day)

Tuesday = write 1 scene (the beginning of your hero’s resistance)

Wednesday = go back and correct any issues with your five scenes

Thursday = go back and correct any issues with your five scenes

Genre: Horror

Premise: After her plane crashes on a remote island, a young biologist fights for survival against a rapidly zombifying army of dead passengers.

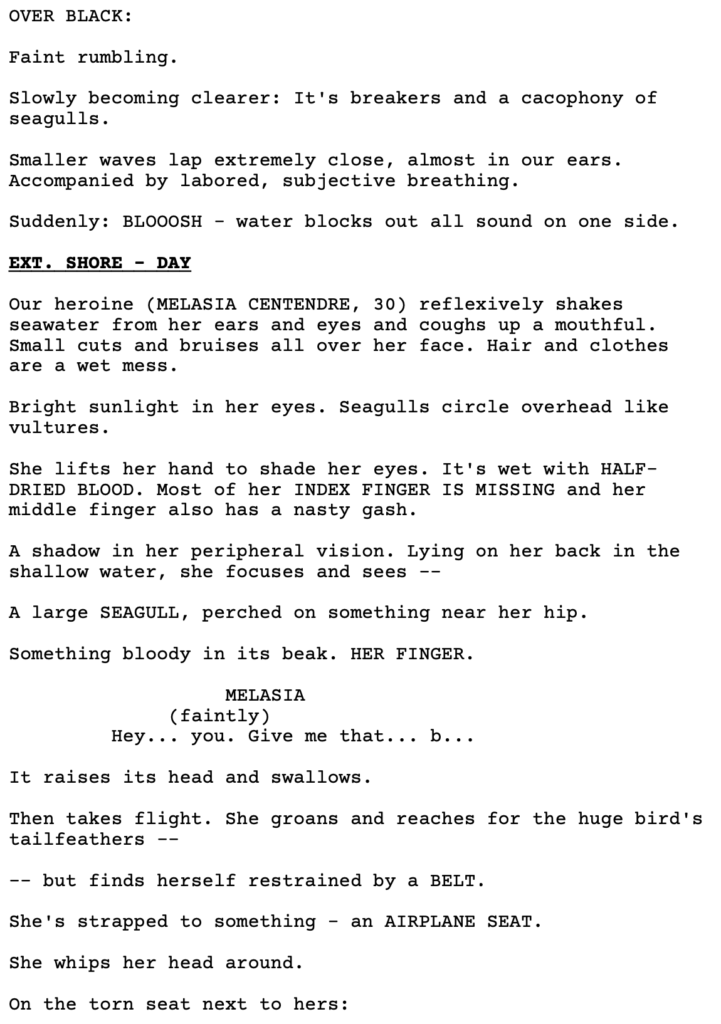

About: Exposition Time. Last year, for one of my monthly Showdowns, I had a First Page Showdown. Contestants entered their first page. No information whatsoever about title, genre, or logline. Just the first page. The readers on the site then voted for the best one. This is the page that won. However, Mikael Grahn played a trick on us. He hadn’t actually written the script. Well, the script has now been written so I thought I would review it today!

Writer: Mikael Grahn

Details: 107 pages

With all this talk about the upcoming First Line Contest, I remembered that I never reviewed the FIRST PAGE SHOWDOWN contest winner. Of course, there were extenuating circumstances. But since I finally have the script, I figure we should review it. Yeah?

Before we do that. I want everyone to see the winning first page. This is the page that appeared on the site and won the contest.

Now, it’s time to see if the other 106 pages are as good.

Melanie Cardot wakes up in the ocean on a plane seat with dead people all around her. One of those dead people was her husband, who was in the seat next to her. Now he’s just a skull fragment and some hair.

Melanie crawls onto the beach and quickly saves a ferret from the plane who becomes her little pal. She’s going to need friends because moments later, one of the dead passengers in the ocean begins to crawl forward. Which shouldn’t be happening considering his skull is gone.

The good news is, it doesn’t seem to want to kill her. Yet. But her fortune dissipates quickly when she sees another headless man walking on the beach. This one in an orange jumpsuit. After getting the heck away from those guys, she finds a rescue helicopter where it appears the man in the orange jump suit came from. But where are the other rescuers?

Soon, more of the dead plane passengers are waking up. Melanie, who’s a biologist, starts to formulate a theory. Something is placing eggs in these bodies and these eggs birth some sort of insect that then takes control of the bodies’ nervous system, basically turning those bodies into vehicles.

Melanie heads up a nearby cliff where she runs into another survivor, an overly nice incel named Rudiger. The two, almost immediately, have to fend off some insect-zombie-dudes with whatever weapons they can find. For Melanie, it’s a jaws-of-life tool from the rescue helicopter. Now that they know what they’re up against, they have to find a way off this island. But how they’re going to do that is anyone’s guess. Cause they’re in the middle of nowhere.

Okay, so, it’s time to get real.

You ready to get real with me?

I read scripts like this alllllll the time. Scripts where people are in some contained location and zombies and/or monsters come after them. Just to give you an idea of how often I read them, I happened to read one JUST YESTERDAY for a script consultation. And I read one last week!

What I’ve learned by reading this particular setup over and over again is that there are two ways to make it work. One is if you give us a scenario or execution we’ve never seen before. Every aspect of the story feels fresh. Now that’s really hard to do because you’re competing against a hundred years of movies. But it can be done if you come up with a really original idea.

The far easier way to make these work, though, is through the characters. If you can create a character we love who is trying to overcome something inside of them and/or a small group of characters who have some unresolved conflict between them and you can explore it and resolve it in an emotionally compelling way, we’ll like your script.

I’m going to grade Niobiota on that scale.

Is this something we’ve never seen before? For the first half of the script, I’ve seen this setup a billion times. These are the same monsters you see in every first person shooter video game. However, later in the script, when they turn into full-on insects, they became more original. The problem was, by that point, the die was cast. We were already bored by the ‘been there done that’ monsters.

Grade: 6 out of 10

What about the character element? We have a dead husband, who was on the plane, so there’s a teensy bit of an emotional tug there. Melanie herself is a biologist, which, while not exactly common in these movies, isn’t that original either. Rudiger has the incel thing going, which was sort of different. But I never connected with anyone emotionally.

Grade: 5 out of 10

So if neither of those two things is near an 8 out of 10, it’s going to be real hard to keep a reader’s interest.

Which is why I say: GET THE HUMAN/PERSONAL/EMOTIONAL component right. Spend more time on that than all the bells and whistles of your concept. Because it’s the easier one to pull off. Why did The Last of Us video game become such a big hit? Because, up until then, zombie games were mindless shooters. The Last of Us developers put a premium on making you fall in love with the characters, connecting with them, giving them internal conflicts and flaws and backstories, and now you actually care what happens even if you go a long time without having to kill any zombies.

Getting back to the plot of today’s script, there were things that I didn’t quite understand. There’s a recurring theme about them disturbing this island. This island wasn’t meant for them. They’re “invaders.” Which is why they can’t be here.

For that reason, I thought these insects that laid the eggs were part of the island. I thought that was the physical manifestation of the theme we were exploring. This is why you can’t come to our island. Because we will infect you and destroy you.

But the insect egg thing didn’t originate on the island. It originated on the plane. So what does “we’re not supposed to be here” mean? Being on this island has nothing to do with anything that’s happened to them. Some crazy insect-infested dude on your plane is the problem.

I don’t know. Maybe I missed the point. But that’s the thing writers have to realize. If we’re not invested in your story, we don’t care enough to figure out the nuances of it. If it’s confusing, we won’t back up and try to figure it out. We’re not engaged enough to care.

This happened recently with Ari Aster and Beau is Afraid. In an interview he agitatedly complained that there were things in Beau is Afraid that people still weren’t talking about online. And it’s like, “Well yeah. Cause we couldn’t connect with your story.” If we don’t love the story, we’re not going to look deeper.

I do think that some of the aspects of Neobiota could be improved through subsequent drafts. I mean, the third act is a disaster and shows how quickly the script was written (It’s an entirely different story that has nothing to do with the island). The question is, is it worth it to perfect this script?

I’ll say this. There may be something here with these insects that control human and animal bodies. If they could emerge by the end of the first act so that you’ve established the uniqueness of your concept early? There could be a path to a fun movie there. But you need to dig way deeper with Melanie. She needs to be more likable and a more complex character and have a more interesting path. You’d need to replace Rudinger. He’s not working. And you’d need to rethink your third act. You can’t just start your movie over.

If you did that… I don’t know. You may have a movie. What do you guys think?

You can download the script here: Neobiota

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It was hard for me to look at this without thinking about how Mikael was rushed writing it. And while the majority of you will never be in the exact same scenario Mikael was in, you will be in scenarios where your time writing the script will come up in conversation. In those scenarios, always be vague. Never say you worked three years on a script. Never say you worked one month on a script. Those details WILL work their way into a reader’s head when they’re reading.

If they were told that the writer wrote the script in a month, the second a cliched creative choice pops up, they’ll think, “This is what happens when you write a script too fast.” Or if a script is really dense and heavily described, they’ll think, “This is what happens when you spend too long on a script. You overwrite it.” Just don’t ever mention that stuff if you don’t have to.

Today, I discuss literary agents and how to know if they really like you. Also, is death by shin guard possible?

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A woman who’s moved into a new home and is buying a lot of things from a giant delivery company learns that she is being used for a new delivery scam.

About: Today we have a director who directed a short film and used that film to create buzz for the feature script, which allowed him to get 25 votes on last year’s Black List, which was good enough for a Top 10 finish. I did not watch the short film because I didn’t want to spoil the script. I wanted the writing to do all the work.

Writer: Russell Goldman

Details: 94 pages

Gillian Jacobs for Julia?

Gillian Jacobs for Julia?

Time to take a small detour to talk about something we don’t typically talk about on the site. This has come up because I’ve talked to several repped writers recently who are frustrated with their reps.

I want writers who think the end all be all is securing an agent to know that it’s more complex than you think. Here’s how it typically works. When you sign up with a rep, they will be your best friend. They will parade your script – the one that got them to sign you – out to the entire industry.

How that script is received will determine how your rep treats you from that point forward. If the script gets a lukewarm response around town (no sale, no options, no assignments), the rep will cool on you *a little bit*. But, you still have one more script to prove your worth to them. So the next script you write is super important. It needs to get sold or secure a big option or lead to an assignment or get genuine A-B level talent attached if they’re going to keep promoting you going forward.

But if that script also fails to make a dent in the industry, your rep isn’t going to do much for you going forward. You will have to do all the work yourself. There is one exception to this, which I’ll share with you in a minute. But first, we’ve got a script to review!

38 year-old Julia Day seems to have just lost her father and has bought a new house. I say “seems” because a lot of details in this script are vague. Julia is a recovering alcoholic and spends the majority of her time trying to fix up her house.

As a result, she’s constantly buying ‘building stuff’ online from an Amazon stand-in called “Smirk.” One of her early packages contains a ski mask by accident. But she’s a self-admitted weirdo and likes it. So she adds it to the many decorations she’s making for her home.

Julia tries to get a job (what that job is is unclear) while occasionally hanging out with her brother or sister, Tat (the gender is unclear), and developing a little crush on her Smirk delivery man, Charlie.

Things get weird when Julia starts receiving things that she didn’t buy – a blender, protein powder, a corkscrew – and she complains to the Smirk people. She’s eventually told that this is a developing scam where people send stuff to customers in order to game the Smirk review system. She should just send the stuff and not worry about it.

But Julia isn’t letting it go that easy. She thinks this is the beginning of an identity theft scam. She starts telling everyone she knows that she’s being targeted but there isn’t enough evidence for her claims to be convincing. One of her windows is broken, for example. She claims someone was trying to get in. But it looks like a harmless accident. As she dives deeper into online delivery scams, Julia becomes obsessed with proving she’s right. But at what point does she accept that this may all be in her head?

Okay, back to the secret to getting a rep who will ALWAYS fight for you.

The one exception to the “2 Script Rep Rule” is if the rep genuinely loves you as a writer. If they really really love your writing, they’ll keep pushing every script you write because they believe in you. Most reps only sign people because they think they can move that script. But if that script doesn’t move, they sour on them quickly.

So always gauge a potential rep to see how much they like your writing. Ask them questions about what they liked in your script(s) and gauge how genuine and thoughtful their responses are. If there’s real enthusiasm and attention to detail in the way they respond, that’s a good indication that they believe in you as a writer. Those are the reps you want. Cause those are the reps who are going to stick with you even if you’re not a shooting star right out of the gate.

I’ll talk about this more in the next newsletter if you guys want me to. Just give me a heads up in the comments.

Back to today’s script.

I’m not going to lie. This one was tough to get through.

I wasn’t surprised to learn that the writer is a director. Cause I sense they’re a director first and they only write because they have to.

Go ahead and take a look at this script. It’s that kind of writing where if you even drift off for a second, you have no idea where you are or what’s going on, forcing you to go back to the top of the page and start reading all over again. The problem is, that the writing isn’t clear enough to prevent you from drifting off again. Which means you keep having to go back to read the pages all over again. As anyone who’s read anything knows, after doing this five or six times, you just give up on trying to re-understand the page and charge forward, accepting you’re going to be ignorant about some things.

I mean, I wasn’t even sure why Julia was home throughout the first half of the script. I wasn’t sure if she had a job or not. When you’re not a screenwriter first, you make the mistake of assuming too much. You assume the reader is in your head with you so you don’t have to make things clear. You may know the protagonist is a teacher so you just *assume* that the reader will figure it out as well.

There *were* some interesting ideas in here. For example, the script covers something called “brushing,” which is a scam where Amazon users will send you an item you didn’t order so that it ships as a “verified” purchase and then they use your account to write up reviews for those products they shipped, since verified purchases push you up higher on Amazon’s “featured” list.

But it isn’t explored in an interesting way. It’s mentioned. Characters seem upset. Julia complains. But it was more annoying than curiosity-inducing. In other words, it didn’t make me want to keep reading to find out what happened next. All it did was make me think, “Oh, I’d never heard of that scam before.”

This is how a lot of things played out in the script. Julia gets a mask in the mail from Smirk. So we think that’s going to be important. But nothing happens with it for half the script until another one shows up. And that one’s just as impotent as the first. We keep waiting for something to HAPPEN in this story and nothing ever does.

Ironically, the best scene in the script is the opening scene. It’s a cold open where this woman receives shin guards in the mail and proceeds to shove one down her throat and use the other one to try and choke herself to death. I’d never read a scene like that before. So it definitely pulled me in.

But then we just get 50 pages of Julia being annoyed. You promised us something and then completely backed away from it.

I see this mistake a lot where writers write their best scene as the first scene. They do this because they don’t need to connect it to anything and, therefore, they can do whatever they want. Which is why it’s so good. But you need to keep the spirit of that first scene in the writing of the rest of your script. Sure, it’s tougher to write engaging material like that if you’re setting up characters and a plot and having to make everything connect. But you have to try!

There may be something to the idea of random stuff being delivered to you. Each item is increasingly weirder. You don’t know how they connect but there’s clearly some message to them. That could be a movie. But the script I just read doesn’t have that clarity of purpose. It’s murky. It stumbles. It has moments but those moments are followed by ten pages that put you to sleep. It needs a writer-writer to come in and add that definition.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you give a reader a wall of text, they will revolt. Readers don’t have the patience. So, please, going forward, pages like this should be condensed to 1/4 of the space. Paragraphs, also, should be a lot slimmer.

As a means of comparison, here’s a page from Mercy, which got Chris Pratt to sign on and sold to Amazon. By the way, Mercy is a script that has 10 times the amount of mythology it needs to explain to the reader. So, if anything, Mercy should be the script that’s overwritten. Instead, the writer understands how important it is to keep the reader’s eyes moving down the page.