Genre: Holiday

Premise: An old miser of a man is visited by three ghosts on Christmas Eve who place him on the path to finding happiness again.

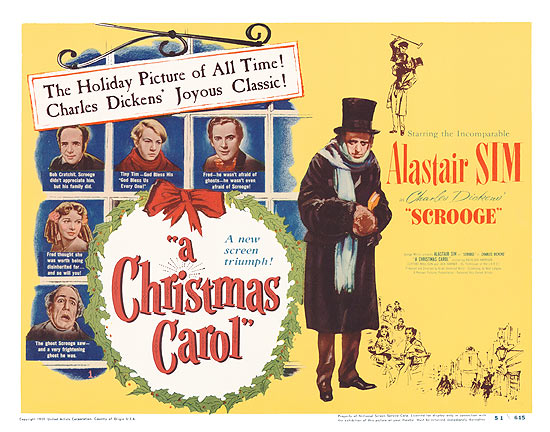

About: Charles Dickens is the original author of A Christmas Carol, which he wrote as a novel in 1843. It has since been adapted into a movie nearly 50 times, starting all the way back in 1901. Today I’ll be reviewing the 1951 version of A Christmas Carol (titled “Scrooge” in the UK) as I believe it’s the best of all the adaptations. The writer of this adaptation, Noel Langley, may sound familiar. He adapted The Wizard of Oz as well.

Writer: Noel Langley (original author of book: Charles Dickens)

Details: 86 minute running time

MERRRRRRY CHRISTMAS EVERYONE

It’s time to open your presents, drink your eggnog and be told by your parents that you’re not doing enough in your life. It’s the Christmas way!

I’m always fascinated by movies that stand the test of time. Of everything out there, these are the films you need to study most. With 99% of movies forgotten within a month of viewing, the stuff that lasts obviously has some secret sauce in it, something you can extract to apply to your own screenplays.

A Christmas Carol has lasted for over 150 years. That means it’s lasted through two world wars, Billy The Kid, a trip to the moon, the Civil Rights movement, the invention of the internet, and even Justin Bieber. In a society so finicky, so obsessed with the next big thing, how is it that A Christmas Carol has stuck around?

You may say, “Oh, well, it’s a Christmas movie. Since Christmas comes around every year, it has an advantage.” Not true. Christmas movies are easily some of the worst movies ever made. They’re probably the hardest “genre” to get right. If anything, that’s working against the film.

I watched “Carol” again this year and it hit me the same way it did when I first saw it as a kid. The difference was, this time, I figured out HOW it was able to do this. I figured out its “secret sauce.” While the answer to its success may not surprise you, you will be surprised at just how simple it is.

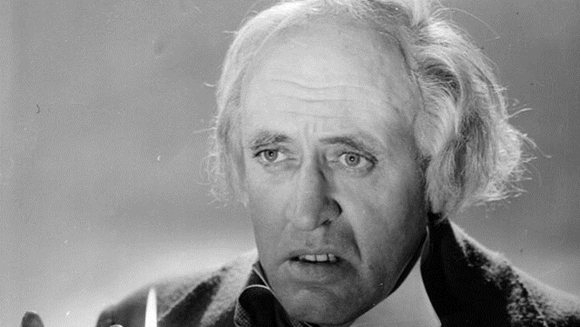

For those who don’t know the story of A Christmas Carol, it follows the most selfish, nasty, heartless man on the planet, Ebenezer Scrooge. A Christmas hater, Scrooge finds himself being visited by three ghosts on Christmas Eve, the ghosts of Christmas past, present, and future. It’s through this journey that Scrooge remembers the joys of life and how important it is to help and be good to others.

One of the most perplexing things about A Christmas Carol is that it flies in the face of everything we’re taught about a leading character. We are told that our hero must be likable, someone an audience can root for. Scrooge is probably the most unlikable person you’ll ever meet. When told that someone he knows might die, his response is, “Hurry up so we can decrease the surface population.”

I wouldn’t classify Scrooge as a hero. I wouldn’t even classify him as an anti-hero. Scrooge IS the villain of this story. And yet he’s our main character. Every screenwriting book and producer in Hollywood would tell you that that’s a surefire way to ruin a screenplay.

While many would use this as fodder for their belief that Hollywood is run by idiots, I’ve actually read far more scripts where an unlikable protag doomed a script than I have asshole heroes making a script better. So why does it work here?

My guess is that we move into the potential for change pretty quickly in A Christmas Carol. There are maybe seven scenes (some of them very short) before Scrooge is visited by his old partner, Jacob Marley, and he’s placed on the path towards change. Were we stuck with this guy for half a screenplay before he was taken on this journey, I’m sure we would’ve been less forgiving.

Another interesting aspect of A Christmas Carol is its structure – or, more specifically – how it lays out its structure for the audience. We’re told, within 15 minutes, that three ghosts are going to visit Ebenezer Scrooge, essentially giving us an outline for the film we’re about to watch.

Many writers assume that if you tell your audience what’s coming, the story will be predictable and boring. But actually, the opposite is true. By telling the audience what they can expect, you have a direct line into their expectations (since you’ve created them!), which means you can now play with them. You can zig where they expected you to zag. You can twist when they were sure you were going to turn. This approach gets great results since the reader is constantly trying to outguess the writer, and if you’re doing your job, you (the writer) are always winning.

But let’s get to the nitty-gritty. The “secret sauce” of A Christmas Carol and why it’s lasted as long as it has. Why generations of children grow up, just like their parents, falling in love with the film and its main character. Are you ready? Care to make any predictions? Okay, here it is:

A Christmas Carol is a deep-set character exploration disguised as a film.

We have ghosts here. We have time travel. We have flashy larger-than-life characters. But this isn’t about that, is it? A Christmas Carol is about one man’s transformation from a cruel selfish person to a selfless happy one. Everything that happens in the movie is built around that transformation.

I can’t stress this enough. So many movies we watch these days are obsessed with the spectacle. And then, because the writer was told to do so by a screenwriting book, they half-heartedly add a few beats to their story about their hero changing. You can smell these scripts from a thousand miles away. The writers don’t WANT to transform their hero. They don’t care about developing the character or arcing them. They do it because they’re told to.

A Christmas Carol IS its character development. It IS its hero’s transformation. Each trip on this journey is Scrooge being forced to examine himself. This is why A Christmas Carol is as timeless as it is. Because spectacle always dies. A chase scene, as awesome as it might be, is a technical achievement at best. But seeing a person come to terms with who they are, and to then transform and change into a better person – by golly that hits us where it counts. Because WE want to change. WE want to become better people.

Ironically, this goes back to my earlier observation. None of this transformation – none of the very thing that makes this movie so timeless – is possible without starting off with an unlikable protagonist. If you had tried to give Scrooge a “save the cat” moment or offset his cruelty by giving him a mother he cares for at the hospital, the transformation wouldn’t have been nearly as satisfying. This man has to start at -100 or the movie doesn’t work.

So where does this leave us with A Christmas Carol? What can we learn from it and apply to our own screenplays? Well, I always think that the unlikable protag approach is a gamble. It’s not that it can’t work, as we see here. But if you don’t get the character just right, the reader will hate them and not want to follow them. The best advice for those wanting to use an unlikable lead is “proceed with caution.”

The bigger takeaway here is to look for stories that are built around character transformations. As time has proven, these are the stories that resonate with audiences the most. And that doesn’t mean you should be writing tiny indie flicks about characters building sewage systems in third world countries. Far from it. Once again, A Christmas Carol has ghosts and time travel. It’s more about finding an idea that’s conducive to character change. Do that and you might be giving yourself the biggest Christmas gift of all – a great screenplay.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: At least one way to make an unlikable hero bearable is to start their transformation into a better person early in the story. If we see that our asshole protagonist is on a path to becoming good early on, we’ll be more tolerant of their faults.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: Pinned behind a wall on the battlefield of Iraq, a sniper’s only communication is the enemy sniper who’s intent on making him suffer before he dies.

About: Dwain Worrell recently found success selling this script to Amazon (their first feature spec purchase). It then finished number 5 on the Black List. Worrell has an interesting story in that, hurting for a job, he moved to China to teach English. Wouldn’t you know it, that’s when he finally found success at screenwriting, and has since moved back. On the flip side, many Chinese children will never be able to read Scriptshadow because of his success.

Writer: Dwain Worrell

Details: 86 pages

I’m not a sniper fan. I thought the 2001 sniper film Enemy at the Gates was the equivalent of watching the Yule log on repeat. I thought the American Sniper screenplay was a government experiment designed to make anyone who read it fall into a deep 24 hour hibernation. And while both of those stories suffered from script issues, I couldn’t help but think that the sniper subject matter was the real problem. Snipers as side characters – as, say, a problem for our hero when he’s trying to make it across a battlefield – that’s interesting. But as the main character, as someone who sits still for a long time and who’s at a safe distance from the action? – there isn’t anything exciting about that.

At least, I thought there wasn’t before I read “The Wall.” Finally, someone has figured out a sniper-centric situation with some actual drama.

The year is 2009. The war in Iraq is over. But as we all know, a war is never really over until the invading side leaves. And the invaders, the Americans, haven’t left yet. They’re at that messy stage of having to take the country they just bombed and build it back up. Which is where we meet our hero, Locke.

Locke, a sniper, and his partner Hobbs, his “spotter,” have been sent to a recent construction zone where the U.S. has been trying to build a school. But when they get there, they find a dozen dead workers, all of whom, clearly, have been shot by a sniper. The only thing that remains of their efforts is a 16 feet wide 6 feet tall brick wall.

After waiting forever to see if the zone is still dangerous, Hobbs inexplicably gets up to go check on the deceased. Surprise surprise, he’s shot by enemy sniper fire, and goes down. Locke tries to go save him but must take cover by the wall to avoid getting shot himself.

Soonafter, Locke is contacted on his radio by a superior who wants to know his position for extraction. It doesn’t take long for Locke to detect a fake accent, and identify the voice as Iraqi. This is “Ghost,” the sniper who has him pinned down.

What follows is a psychological battle of wits, as Ghost questions Locke on everything from American slang to a previous incident where Locke’s former friend and spotter mysteriously died on Locke’s watch.

As a deadly wound slowly bleeds out, Locke has an hour at most (URGENCY – YAY!) to figure out where the sniper’s hiding, as killing him is his only chance at getting out alive.

This is a really clever spec idea. Something we talked about recently was the difference between a “script” and a “movie.” Sometimes something reads really well on the page, but it doesn’t transfer well to screen. And the knock on the Black List is that it has a lot of good scripts, but not many of those scripts are “movies.”

When you contain your story, it becomes even harder to write a movie because you’re limited to one place. Movies like lots of places, lots of action, movement, changing scenery. So something where, say, three people are locked in a room during the apocalypse, might read well, but visually it’s going to get pretty boring on the big screen.

With The Wall, even though it takes place in a single area, it’s a very cinematic single area. It’s a battlefield. And the threat of our main character being sniped at any moment gives it the same kind of intensity you would feel in your typical scene from Mission Impossible 5. Put simply, despite its small scope, this FEELS like a movie.

And Worrell mixed in a couple of clever devices to heighten that intensity. Another writer may have made Locke the lone character in this script. That’s the “first idea” version of this story. Instead, we have Hobbs, who gets taken down on the battlefield. But the clever part is, Hobbs isn’t dead. And Ghost doesn’t know he’s not dead. So while Locke is having this conversation with Ghost, Hobbs uses minimal movements to scan the area, to try to locate where Ghost is hiding. The whole movie we’re desperately hoping he locates Ghost before getting caught.

Worrell also uses a mystery box of sorts with Ghost. Ghost knows who Locke is. He knows his rank, his experience, even specific details from his life. So this whole time we’re trying to figure out who Ghost is and how he knows these things.

Finally, Worrell gives Locke an unresolved event from his past that the two characters can discuss – the death of his former spotter. What starts out as a straightforward story of a soldier dying on the battlefield turns out to be a lot more complicated. If Locke and Ghost only have surface-level things to talk about (sniping, their religious beliefs, their opinion about war), the dialogue’s going to get boring fast. We need that thread that we can keep coming back to, that the audience is going to want an answer to. That’s what the spotter thread did.

There were a few things I thought could’ve been done better though. I couldn’t, for the life of me, understand why Hobbs would walk out into a group of 12 dead guys who had been shot by a sniper. I’m not a soldier but something tells me that’s a really dumb move.

I wished Worrell would’ve better explained who and what a spotter was. I’m not familiar with the army so I wasn’t even aware there were spotters. This becomes very important (spoiler) later on when Ghost’s spotter comes into the mix and he’s in a different location. My understanding of spotters was so limited that I didn’t get how a spotter could not be next to his sniper.

Yes, it’s tricky to figure out how to convey details like this without getting too exposition-heavy. But that’s one of the requirements of being a writer. You’re counted on to find creative solutions to tough problems.

Finally, I wanted more from the ending (reverse spoiler). There were all these hints during the story that the enemy sniper may have been one of their own (an American sniper). I was expecting a big twist at the end, one that possibly tied into Locke being responsible for his old spotter’s death (was he still alive? was he behind this??). I guess this was based on a real story though (Ghost was a real Iraqi sniper) so Worrell wanted to stay true to that. But something about this script was begging for a last second twist, and I was a little disappointed when we didn’t get one.

Still, this was a well done job by Worrell and a really cool little screenplay. Can’t wait to see what he comes up with next.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The inner monologue versus the outer dialogue. A conversation is never a straightforward thing where the world stops while words are exchanged. Characters are usually thinking about something else when they speak, and what they’re thinking about can help inform the scene. You may be talking to your boss, for example, but thinking about your date with his daughter later. You might be at a party talking to someone you don’t like, and therefore scanning the room, looking for someone to save you. You may be talking to a teacher in a parent-teacher conference, who’s telling you that your kid isn’t paying attention in class, and all you’re thinking about is, “That’s because you’re the worst teacher in America.” In The Wall, Locke spends almost the entire conversation with Ghost looking for a way out. He’s never just having a conversation. He’s strategizing, manipulating, hunting for a clue as to Ghost’s whereabouts. That’s a huge reason why the dialogue pops here. Because the inner monologue is contrasted against it.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: (from the actual Black List) A nerdy high schooler, who fancies himself an amateur photographer, attempts to create a “Swimsuit Issue” featuring his high school classmates in hopes of raising enough money to go to summer camp.

About: The Swimsuit Issue finished number 3 with 35 votes on this year’s Black List.

Writer: Randall Green

Details: 105 pages

You may not realize it, but I can hear your brain right now.

I’m inside of your head. I saw an ad on Craig’s List for it recently and figured I’d sublet. The nice thing about being inside someone’s head is that you can hear things not even they can. You wanna know what I hear your brain saying while your mouth tells everyone that the Black List is bullshit? That it’s rigged and the quality of the scripts suck and no one cares about it any more? Your brain’s whispering, “I wish my script made the Black List.” Because like it or not, it’s an opportunity to be celebrated for your writing. And you don’t get many of those as a screenwriter.

So today, I’m going to fill you in on a few reasons why The Swimsuit Issue made the Black List (high up, for that matter) and your script didn’t. Hopefully, this will gear you up for next year’s attempt at the list. But first, let’s break down the plot.

Our hero, 15 year old aspiring photographer Zach Rosen, is sort of like a combination of Max Fischer (Rushmore), Napoleon Dynamite, and Ferris Bueller. He’s a high school kid who’s a little bit different. Well, okay, a lot a bit different. When we meet him, he’s been called into the principal’s office for hawking pictures of his half-naked plus-sized housekeeper, Esmerelda.

Zach doesn’t see this as inappropriate, however. He sees these photographs as art. And since he’s just moved into a new town and a new school, art is all he’s got. Well, except for his gorgeous girlfriend, Jenna, who he sees once a year at summer camp.

Unfortunately, Zach’s about to get some bad news. Because his father recently lost his job and his mom split up with him, the family (which includes Zach’s older drug-addict brother, Charlie), doesn’t have the cash to send Zach to a fancy camp this year. Which means Zach can’t see Jenna. Which means Zach needs to think of something fast.

So he comes up with the nifty idea to do a swimsuit issue of the hottest guys and girls at school and sell it. But he needs to make friends first. Luckily, he crosses paths with the “Greta Gerwig-like” Dana, a cool chick who seems to have it all going on – she’s confident, smart, cute, funny. Except Dana kind of gave one of the teachers a handjob in the cafeteria and he got fired. So everybody hates her.

Still, Zach and Dana team up, recruiting the hottest boys and girls they can find, culminating in a wild party at Zach’s place where he gets the photos. During this time, unfortunately, Zach’s camp girlfriend breaks up with him. His father goes on a drunken bender. His brother steals Dana right from under his nose. And everything about Zach’s future is destroyed.

Will Zach recover? Will he mend his relationship with his deadbeat brother and retain a friendship with Dana and Jenna? Or will he become just like the other members of his family and give up on life?

Okay, so I promised you answers on why this made the Black List and your script didn’t. So let’s not waste any time. Get your pens out my scribble-hungry brethren.

1) It’s a comedy that cares just as much about drama as comedy – The Black List rarely celebrates out-and-out broad humor. Agents, producers, and development folks like comedy writers who can explore drama in their comedies, and then find the comedy within that drama. There’s a whole lot of intense family shit going on in The Swimsuit Issue. It’s not just shit jokes and characters bumping into things.

2) It’s edgier than your typical comedy – The Black List likes when you go beyond the safe predictable boundaries of a genre, especially comedy. Zach’s doing lines of cocaine by the end of this script. We’ve got inappropriate student-teacher relations. In other words, the worst thing that happens in this screenplay isn’t a guy losing his girlfriend.

3) Deals with real complex relationships – The most forgettable comedies are ones that put zero effort into exploring relationships on any honest level. As this script goes on, we realize that Zach and Charlie’s relationship is really complicated. He’s an addict whose expensive trips to rehab have had a direct impact on Zach’s life. These two need to hash it out by the end of the story or we won’t be satisfied.

4) Unexpected dialogue choices – People often ask how I can spot a “pro” script over an “amateur” one. One of the easiest ways is dialogue choice. When a character says something, does the other character respond with a generic line or a line we’ve seen a million times before? Or is the response unique and unexpected? Most of the lines in The Swimsuit Issue are unique and unexpected. For example, later in the script, Zach’s mom says to him, “I want you to visit your brother this afternoon.” Now go ahead and write down how you’d have Zach respond to this. I’ll wait. Hopefully you didn’t write something like, “No.” Or, “Not gonna happen.” Okay, ready? Here’s his response, which is quite funny: “That’s eight or more unlikely steps from happening.” Even if you don’t like this line, note that it’s not a BORING line. It’s not an EXPECTED line. That’s the point.

Now the other day when I was breaking down this logline along with the rest of the Black List, you may remember me saying that I was worried the script didn’t have any stakes. “A kid makes a swimsuit issue for his school so he can go to camp” doesn’t sound like a very important journey.

But as we’ve discussed before on the site, stakes don’t have to mean the world is about to blow up. Stakes are relative to the situation. If a character wants something badly enough, then to him (and us), the stakes will be high. It turns out the missing ingredient in the logline was that the love of his life was at camp. And this is the only time during the year he’ll get to see her.

That tiny detail added the stakes to all of a sudden make this story worth telling. However, don’t wait until someone reads your script to figure that out. Include it in the logline. Because stakes are one of the key ingredients in getting someone to want to read a script. The new logline for The Swimsuit Issue, then, would be something like: An eccentric teenager attempts to create a “Swimsuit Issue” featuring his high school classmates in hopes of raising money to go to summer camp, his lone opportunity to see the love of his life.” That’s a bit rough but you get the point. Include those stakes!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script had a goal (create the Swimsuit Issue to raise the money to go to camp). It had stakes, which we just pointed out. But it didn’t have urgency. I never felt like Zach was under any pressure to hurry up, and that definitely affected the story. The simple feeling that “time is running out” is an easy way to add intensity to your story, and is therefore recommended.

What I learned 2: I’ve found that 105 pages is the PERFECT length for a comedy script. If you’re writing a comedy, this is a great script length to aim for.

Sadly, my friends, there are no amateur offerings today. The next TWO Fridays are off, so last week’s round will be reviewed in the New Year. But I don’t want to leave you with nothing, so I’ll share something I thought about all of yesterday for some reason. My question is, will Guardians of the Galaxy be the equivalent of this generation’s Raiders of the Lost Ark? Is Chris Pratt going to go on to be a Harrison Ford like movie star for years to come?

It’s so easy to think, “Of course not! Movies then were so much better!” Well, a big reason they were “better” was because it was your first experience seeing that kind of movie, just like it will be this generation’s first experience seeing this kind of movie. I guess I’m trying to figure out if a movie like Guardians is really truly good, or just benefits from a lower overall bar. And is nostalgia keeping us from comparing the two objectively? I’m particularly interested in hearing from the under 25 crowd that didn’t grow up idolizing Raiders. Oh, and as long as I have you here with 5 days left until Christmas, make sure to stuff your digital stocking with Scriptshadow Secrets, which is only $4.99! $4.99 to become an infinitely better screenwriter. Uhhh, bargain!

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Comedy/Mockumentary

Premise (from writer): A tightly-wound retail store manager on the brink of being fired struggles to prove his worth against a crew who hates him, a competing retailer (who happens to be his ex-girlfriend) out to sabotage him and a mall full of crazed Black Friday shoppers.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Because it is a story about working in retail which means that while it’s written as a comedy, it could easily pass for a horror, a drama, a thriller, an action-adventure or any of the wild aspects that make working retail soul-crushingly awful and occasionally (oh so occasionally) great. Also, this script is very much a product of Scriptshadow. I studied screenwriting in college, but spent many years caught up in absurdly grand fantasy-adventure screenplays that were really novels written in Final Draft. And then I stumbled upon Scriptshadow, learned some new lessons, refocused my writing, and set out to create screenplays that were actually screenplays. “Black Friday” is one proud example.

Writer: Jason Tropiano

Details: 104 pages

Man, you guys make it hard on me. There hasn’t been a clear winner on Amateur Offerings for awhile. And when that happens, it means I have to decide. I hate deciding!

I ended up going with Black Friday for a couple of reasons. I think a comedy surrounding Black Friday is a movie. I can see the poster. I can see the trailer. Also, it’s that time of year. So shouldn’t we be featuring a holiday script? True, Inhuman had more votes, but I was only going to give it a second coveted Amateur Friday slot if it blew away the competition. There are only 55 Amateur Friday slots a year so I like to use that day to see as many new voices as possible.

It’s a month before Black Friday, and Jonathan, the manager at American Outfitter’s Roosevelt Mall location, isn’t wasting any time getting ready for the biggest day of the year. You see, Jonathan has a baby on the way and he hasn’t exactly been knocking it out of the overpriced hipster clothing park. All signs point to him being fired unless he makes this the best Black Friday in store history.

That won’t be easy though with a young disinterested sales team that has bigger plans in life than working in retail. Jonathan also has to contend with former flame Kennedy, who manages the Abercrombie & Fitch clone, Charley & Waves, across the way. Kennedy divides her time between finding anorexic looking sales-models to stand outside of her store, and plotting her revenge for Jonathan dumping her.

When the big day finally comes, the shenanigans are on. Kennedy fights way below the belt, printing up 50% off flyers for American Outfitters that the clueless sales team at AO start honoring, and having one of her employees defecate in one of AO’s fitting rooms. If Jonathan is going to last another day at this job, he’ll have to rally the disinterested troops, fend off all the sabotage, and clear things up with Kennedy. All before the closing bell rings at 10 pm.

The other day, someone said in the comments section that you shouldn’t send a comedy to Scriptshadow because the people who frequent this site don’t celebrate comedy – or, put more bluntly, they wouldn’t know what comedy was if it shat on them in a changing room.

I would rebut this. Comedy struggles to gain acceptance in every venue. It doesn’t get celebrated in screenplay contests. It doesn’t get celebrated during Awards shows. There aren’t that many comedies on the Black List.

The problem is that it’s really hard to be funny. Especially on paper. You don’t have the benefit of a comedian delivering your lines or a physical actor who can just contort his face in a way that makes you laugh. All you have is your words.

So it’s not that we here at Scriptshadow hate comedy. It’s that rarely do writers meet the bar the genre requires.

So how does Black Friday rank in regards to this bar? Well, from a story perspective, there are some good things here. I like how Jason created some really high stakes for our hero, Jonathan. Jonathan is on the outs at the company. He’s got a kid on the way. Black Friday is his only opportunity to save his job. We have a proper villain, Kennedy, who had a personal relationship with Jonathan (the personal relationship adds another layer to the story) and who creates plenty of obstacles to prevent Jonathan from reaching his goal. So structurally, I thought Jason did a good job.

But in regards to the funny factor, I don’t think we’re there yet. To start, utilizing the mockumentary style feels dated. That was all the rage five years ago, but I think people are looking for something new now. Ironically, telling comedy in a “straight” fashion feels fresh again.

I point this out because there were maybe 20 mockumentary-interview-specific jokes I didn’t laugh at because I’ve seen them all before. For example, when the clueless customer digs through their purse with 80 people in line behind them – then we cut to an interview shot of the salesperson giving a “Really?” look into the camera. That joke is too familiar at this point. It’s safe. So that’s 20 jokes right there that didn’t hit for me. I saw them coming a mile away.

So where do you find the funny? You find it in situations and in characters. That’s really your main job when it comes to comedy writing. You have to create funny characters and seek out funny situations. The only character I genuinely laughed at was Woo, the stock-boy with a penchant for extremely inappropriate rap music. He really stood out.

And the only situation that resonated was the fake 50% coupon debacle. But I don’t think enough was done with it. I like the idea of everybody coming to their store, seemingly exactly what they want, but then it getting completely out of control once they all start demanding half-off. The thing is, this problem was solved within a few minutes. There needed to be that moment where Jonathan secretly honored it for one problematic shopper to get him out of the store, then tried to cut the discount off. But by that point, everyone’s found out that the customer got the discount, and they’re not leaving until they get it too. Old customers also need to come back and retroactively demand the discount. It needs to get to riot levels. This is Black Friday. Excessive situations are expected.

Situational comedy can be fun to figure out. But it’s something you really have to spend time on. I would go so far as to say that if you’re writing a comedy, sit down for an entire two days and come up with 50 concept-specific situations, then cherry pick the best. Cause if you’re only picking from a nest of 4-5 ideas that popped into your head, you’re not going to be able to compete with the truly hilarious guys.

Finally, I’ll say this – the more I read of Black Friday, the more I wondered if this was the right approach. I mean, the script’s called Black Friday, but we start a month before Black Friday. We should be starting ON THE DAY. And I wondered if a Breakfast Club type approach might have been better. One day. Seven shoppers. Each with their own specific goals (maybe not all of them to get gifts) and, of course, everything under the Christmas tree goes wrong. Also, when I think of Black Friday, I don’t think of clothing stores. I think of big box retailers like Best Buy and Walmart. That seems to be where the real craziness is. And yet those businesses were left out. But even if you’re interested in mall-like stores, I’d go for more of a variety. A clothing store, a sports store, a candle store, a Radio Shack type store. We should be getting the entire scope of the mall, not just these two locations. That’s probably how I would’ve tackled it, at least.

There’s a lot of love here though. I can feel Jason’s own experience in retail shining through. But something’s missing and I can’t pinpoint exactly what it is. What did you guys think?

Script link: Black Friday

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Worst case scenario situations. One way to find laughs is to think of the worst case scenario for a character, and then put them in it. So for example, let’s say one of the employees at American Outfitters is OCD OBSESSED with his displays. That’s literally all he cares about –everything being folded perfectly and placed perfectly and the area being exceptionally clean. What’s that character’s worst case scenario? Each of you are probably thinking of something different. But chances are, it’s funny. Maybe, for example, a mother comes up and starts changing her baby’s diaper on the most important display in the store – the one OCD EMPLOYEE was working on all night! She’s just carelessly placing the dirty diaper on the most expensive shirt as if it’s nobody’s business. This approach is an easy way to generate 3 or 4 big laughs in a movie.