Genre: Western

Premise: A group of cave-dwelling cannibal Indians abduct a woman. The race is on to rescue her before she’s turned into lady-stew.

About: S. Craig Zahler wrote an amazing script five years ago called “The Brigands of Rattleborge” that is still unmade. Blimey! My understanding is, like a lot of projects, it’s stuck in some development snafu that, even though the company who has it isn’t able to do anything with it, they’re not going to allow anyone else to do anything with it either. And this is why some great movies never get made. While Zahler’s written a handful of scripts since, it looks like he’s tired of the waiting game. So he’s doing what more people in this town should do – he’s taking his career into his own hands and directing Bone Tomahawk himself. This is one of the sweetnesses of being a great writer. Sooner or later, you’ll have the opportunity to hold people hostage with your talent. You say to them, “You get my hot script, but only if you let me direct it.” The project has secured a nice looking cast that includes Patrick Wilson, Kurt Russell, Matthew Fox, and Richard Jenkins. It comes out next year.

Writer: S. Craig Zahler

Details: 125 pages

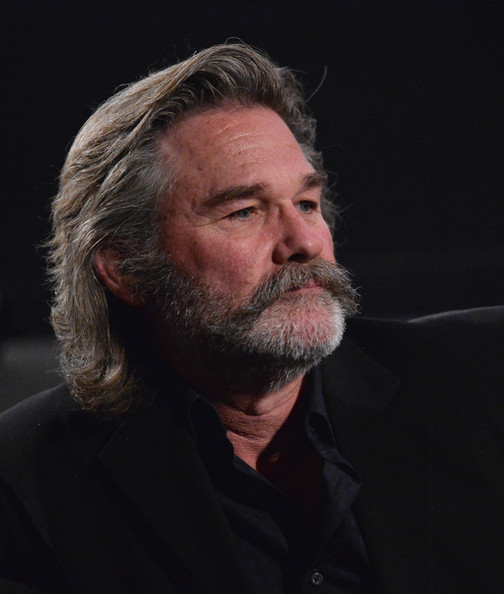

Kurt Russell is bringing his Western-perfect face to Bone Tomahawk

Kurt Russell is bringing his Western-perfect face to Bone Tomahawk

Despite my being far from the biggest Western fan, Westerns always seem to end up in my Top 10. It’s doubly surprising that a script like “Brigands” would find its way there because it commits one of the cardinal sins of screenwriting – the rule everyone agrees you don’t break. And that’s excessive description.

Excessive description is saved for novels (which Zahler writes as well). In the screenwriting world, the goal is to move the reader’s eyes down the page as fast as possible. The huge distinction that so many writers forget is that while novels are the end of the line for that writing process, screenplays still have one step to go. They’re the “proof of concept” for the end of the line. Because so many other scripts are ALSO vying to get to the last step, readers and producers need to get through screeplays quickly, so they can go on to the next one.

But here’s why Zahler seems to get away with breaking this rule. A) He’s a writer who excels at description and B) he writes in the genre ideal for description – Westerns. Westerns require the writer to set a mood, a tone, to pull them back into that time and into that world. You need a little extra description to do that.

With that said, I’ve watched a lot of writers try to pull off the same thing and they’re just bad at it. They don’t focus on the right words or the right phrases. They’re clunkier, less imaginative. Description is about finding those power words that provide a perfect conduit to the moment and if you don’t have that talent, you don’t want to play in that sandbox. Which is fine, because for almost every other genre, you want to keep the description short and sweet.

Bone Tomahawk begins with two pieces of shit named Buddy and Purvis, who have just murdered a group of people. When they believe they hear others coming, they retreat to a nearby mountain to hide. Weaving their way through the mountain crevices, they find a bone-laden graveyard. Spooked, they try to get away, but not before an arrow pierces Buddy’s neck, an arrow with a tip made from a bird’s beak.

Purvis, the dumber of the two, hightails it out of there to the nearby town of “Bright Hope.” He’s immediately tagged as a suspicious character and, in a confrontation with the sheriff, shot. Samantha O’Dwyer, the local nurse, is brought in to clean the wound, but when a group checks on the two, they find them gone. In their place is another one of those bird-tipped arrows.

Samantha’s husband, Arthur, is pissed and wants to go after the kidnappers, but due to a recent accident is on crutches. Still, he convinces the local sheriff, an Indian hunter, and an older gentleman, Chicory, to let him come along and get his wife back.

So that’s what the four do. Well, sort of. The next 60 pages take our heroes through the endless plains of the old West as they track these cannibals back to their home. Along the way, they lose their horses, which means Arthur must stay behind. But as the others continue on, Arthur never gives up, vowing to save his wife.

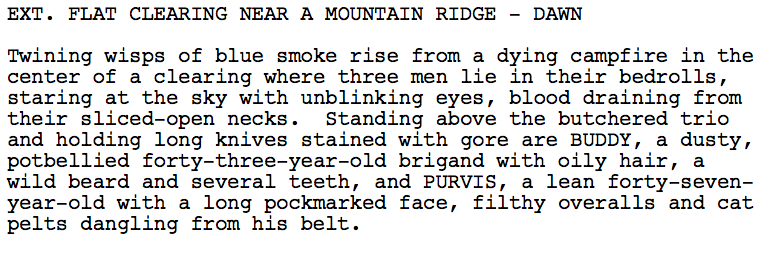

To give you an idea of what I was saying earlier, here’s the first paragraph of Bone Tomahawk.

That’s a sure way to send the average reader packing. But I’m going to tell you why it works, at least in this instance. Read the first sentence again. That’s not just a description. That’s a story. Three men are dead, the blood still draining from their throats. Now had this only been description for description’s sake (no deaths), the paragraph would’ve been a tougher sell. But this is far from a boring paragraph.

Alas, I wish I could say the same about the rest of Bone Tomahawk. The script truly does start out great, with the murder, the emergence of these mystery cannibals, and with Samantha abducted. You’ve got all the elements in place for a classic GSU tale.

But Zahler went ahead and forgot the “U.” Once our characters are on their way, very little happens for a long time. It’s a strangely pedestrian exploration of the West, with most scenes limited to characters yapping away about trivial topics. For example, one scene centers on Chicory’s confession that he’s lousy at reading books in the tub, as the books keep getting wet. Far from edge-of-your seat storytelling.

When you send a group of people off on a journey, the drama needs to come from one of two places. Outside or inside. As cool as our bone tomahawk cannibals are, we see them a few minutes in the beginning, twenty minutes at the end, and that’s it. Bone Tomahawk runs into the most classic pitfall in all of screenwriting – the boring second act. And that’s because there isn’t enough happening. Not to our characters from the outside (their horses are stolen but that’s it) and not from the inside either.

Every once in awhile, characters would have a minor disagreement about something (“Why did you shoot at the Mexicans?”) but other than that, everyone seemed to be on the same page. If you’re not going to throw a lot of plot twists and plot points at us (exterior stuff), you need to create problems between your characters (interior stuff), either unresolved things arising from their pasts or issues that develop as they go (challenge to authority, differences in philosophy, people having breakdowns, etc.).

That was one of the great things about Aliens. Nobody agreed on anything. These disagreements caused tension and conflict which resulted in drama. This amongst a story that already had one of the most intense EXTERIOR conflicts in history – those terrifying aliens. That’s the way I’d prefer writers do it. Create conflict in both places, interior AND exterior.

Then again, I understand that this is a Western, and Westerns move at a different pace. That’s something I’ve never been completely comfortable with. I know, technically, that you’re supposed to allow Westerns extra time to build. But you have to put a limit on it at some point, right? There has to be mark on the dial where you say, “We need to go faster here.” I’m sure Western purists are going to be more forgiving of the pacing here. But for me, not enough happened in the allotted time.

Another curious aspect of Bone Tomahawk is that we’re not sure who the hero is. That’s a very “studio-ish” note. That you have to have a single hero. But it truly did hurt the read for me.

I assumed that Arthur (Samantha’s wife) was going to be our hero. But then he barely speaks on the journey, to the point where we often forget he’s there. The character who spoke the most and acted the most was the sheriff. So you’d think he might have been the hero. But his is the least personal journey here. He seems to be acting only out of duty.

Arthur does make a late push to lead the charge, but he’d been so absent by that point, that I was no longer invested in him.

I’m super-curious what Zahler is going to do as a director. He seems like a deep intense guy, sort of the screenwriting equivalent of Cormac McCarthy. With that being the case, I know he’s going to bring something extra to his vision. As a screenplay, though, Bone Tomahawk moved too slow for me, and didn’t have exciting enough characters to keep those slow sections entertaining.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Yesterday we talked about the value of adding uncertainty to your story. The more certain the audience is of what’s going to happen, the more bored they’ll get. To me, these plains gave the story such an opportunity to create an endless thread of uncertainties. But everything pretty much went according to plan. Even the surprises (their horses getting stolen) were predictable. It’s really hard to keep the audience entertained when you’re not giving them anything they don’t expect.

No, Robert McCall didn’t get me in my sleep last night. But sleep is definitely the main suspect in today’s mystery. For the first time since I began Scriptshadow, I actually fell asleep while reading yesterday’s review script. Apparently reading and giving notes on four scripts in a single day is my limit. Boy did I have some sweet dreams though.

Since there’s going to be no review today, I can tell you something big I learned after reading all of those scripts. I started to notice early on in the 4-pack that 80% of the scenes in these scripts had zero drama. They were all straightforward, all executed on the surface. Surface-level scenes are almost all catastrophes for being so boring. For example, “Don” might need to tell “Judy” that they need to take money out of the bank. So we’d have a 2 page scene where Don told Judy that they needed to take money out of the bank.

The more of these scenes I read, the more I realized why they were so bland. In every situation, we were certain what was going to happen. There are lots of ways to make a scene work, but one of the best ways is to through uncertainty. Let me give you an example. Let’s say that “Frank” wants to break up with “Ellen.” If Frank goes into the scene and says “Hey, I had something to talk to you about.” “Oh really, what’s that?” “Well, it’s a big deal.” “Okay, tell me.” “Umm, I think we should break up.” If you write the scene that way, with everything going according to plan, it turns out to be a boring scene.

But if you go into the scene with the intent of creating uncertainty, of not doing the expected, you can bring life and drama to the scene. So say Frank comes in and says, ‘Hey, I had something to talk to you about?” and Ellen says, “Oh? I had something to talk to you about as well.” Frank is momentarily thrown. “You do?” “Yeah.” Whereas in the first example, we knew where the scene was going, by unleashing uncertainty into the re-mix, we created a more interesting scenario. Frank’s plan is now all messed up. He’s forced to reevaluate his approach. We, the audience, are the benefactors because now we have no idea where this scene is headed, which means we’re paying more attention.

As I kept reading the scripts, I noticed that you can create uncertainty before the scene starts (let’s say, before Frank gets to Ellen’s, he gets a text from her: “We need to talk.”) or you insert it as the scene is going, kind of as a surprise. A situation where we think we know what’s going to happen that turns into one where we have no idea what’s going to happen is an exciting scenario. The ultimate take-away here is that a scene plays out in a more suspenseful manner if we don’t know where it’s going. If we think we know where it’s going and you take us there? You’ve failed to entertain us.

So I challenge you all. Go find an “expected” scene in your script, one where everything goes according to plan, and add an element of uncertainty. Either before the scene or during it. I’m betting the scene becomes a lot better.

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: (from IMDB) A man believes he has put his mysterious past behind him and has dedicated himself to beginning a new, quiet life. But when he meets a young girl under the control of ultra-violent Russian gangsters, he can’t stand idly by – he has to help her.

About: As you can see just by looking at my Top 25 list (over to the right), I hold this script in high regard. So I was more than curious how it would play out on the big screen. The project had a bouncy development process. Denzel was always attached, but it kept switching directors, moving from Rupert Wyatt (Rise of the Planet of the Apes) to Nicolas Winding Refn (Drive – another favorite script), and I want to say one other director before it eventually reteamed Washington with Antoine Fuqua. Let’s be honest here. Fuqua hasn’t been hitting it out of the park lately. But anyone who directed Training Day is an okay choice by me. The film opened this weekend at number 1, surprising a lot of industry analysts, who thought it would land in the 23-25 million dollar range. Instead it finished with 35 million.

Writer: Richard Wenk

Details: 2 hours and 12 minute runtime

Writer Richard Wenk initially passed when he was offered The Equalizer. But the second time he was approached, the assignment came with a new piece of play-doh. Denzel Washington. Wenk, who had promised himself to only write for directors from this point forward (if you write something without a director attached, you’ll likely have to start all over again once one does join, so why bother?), changed his tune once the name “Denzel” was uttered.

But that still didn’t guarantee anything. Denzel has lots of people “officially” writing projects for him. If you don’t deliver, if the script doesn’t excite him that first time it hits his eyes, you’re SOL. So Wenk and the producers worked really hard to get it right. The result was one of the best scripts I’ve ever read.

It really is a master class in writing. Everything is so sparse, from the description to the dialogue. And that’s not surprising when you hear Wenk talk. He claims his m.o. as a writer is looking for ways to eliminate all the unnecessary words from his work, to slim the script/story down to its bare essence. And you see that here.

The question with The Equalizer script was always, is it too generic? The story is SO simple that it risks being a retread of lots of stuff we’ve already seen before. I didn’t see that happening. But you never know. If the director doesn’t pay attention to those little details the writer worked so hard to integrate, an “Equalizer” can easily turn into an “Abduction.”

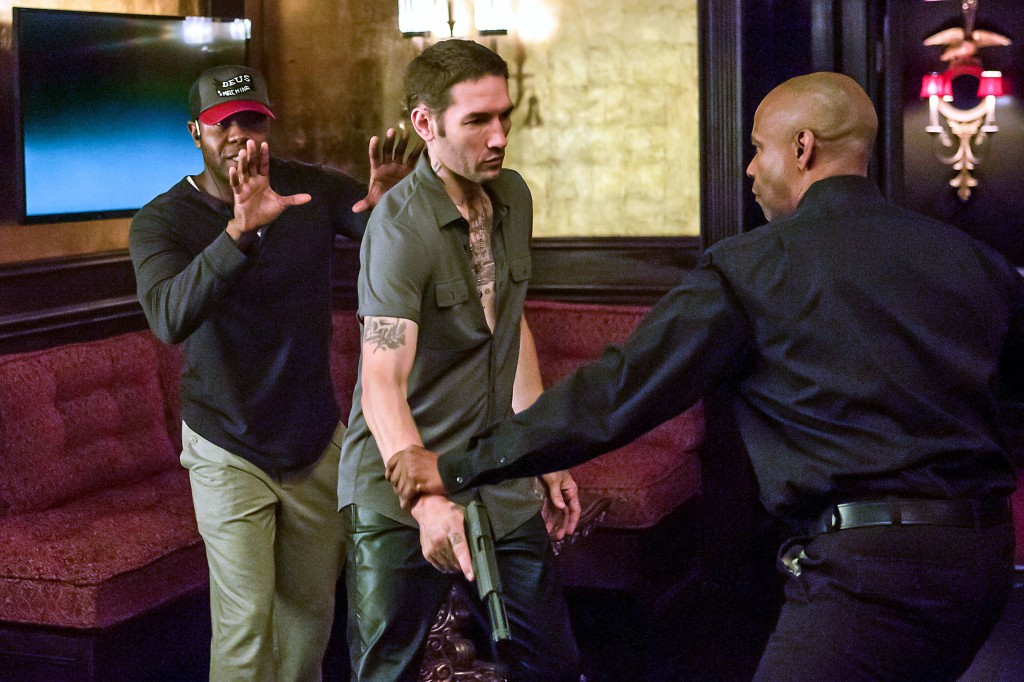

For those who don’t know anything about the film, it’s about a 50-something “nobody,” Robert McCall, who lives by himself and works at Home Depot. He develops a friendship with a young hooker (Chloe Moretz), who’s nearly killed by her Russian pimps. We learn that McCall used to be a CIA officer, and knows about 7000 ways to kill a man. He takes down the pimps to set the hooker free, only to learn that the biggest Russian mafia boss in the world has put a price on his head.

So what did they change from the original first draft? And how did it affect the film? They didn’t change much. The most well-publicized switch was changing the 30-something hooker to a 17 year old. Here’s the thing you gotta remember when you make a key change in your script. Since you’re going to both lose something and gain something, you have to make sure that you gain more than you lose.

What they lose by going from a 30-something to a 17 year old, is a more flirty love-interest type of relationship. Audiences like these relationships, even in a script like this, where the romance doesn’t take precedence, because they like the idea that our main character and this woman might get together in the future.

You don’t get that when the girl is 17. It’s more of a friendship. What they were banking on, and this was specifically a note from Sony studio head Amy Pascal, was that we would sympathize and care more about Teri (the hooker) if she was just a girl. It’s a solid argument. The entire script hinges on us buying that McCall would kill five random men to save this one girl he barely knows. And if we’re seeing a girl in danger as opposed to a grown woman, we’re more likely to believe McCall will stick up for her.

It worked. I’m not sure how much less I would’ve sympathized with Teri as an adult, but that additional layer of her being a scared little girl affected me. A smart call.

Some of the other changes were more subtle, but interesting nonetheless. In the script, McCall was a tidy dude, born out of his upbringing in the military. But in the film, McCall is OCD. He has to make sure things are lined up properly. He’s always rearranging things on desks and on tables. In the script version of the famous “Take-Down Russians” scene, McCall walks back to the door and locks it. Here, he opens and closes the door three times, the echoes of an OCD tick.

There’s no doubt in my mind that this is something Denzel Washington brought to the character. As an actor, that’s your job. You have to find ways to play the character that make them original, make them truthful. But that’s not how it should’ve gone down. And I’ll tell you why in the “What I Learned” section later.

Seeing the finished product also helped me notice a few things I missed in the script. First, you guys know how much I love underdog heroes. They are the heroes audiences root for the most. Audiences also love badasses. They love John McClane and Iron Man.

Therefore, I realized how genius it was that they somehow created a hero in The Equalizer who was both. They got a 2-for-1 deal! McCall is the most unassuming man in the room. Couldn’t win an arm-wrestling contest with a 5th grader. And that’s why we fall for him. He’s one of us. And yet it turns out he can take down the entire fucking Russian Mafia! How rad was that choice? Could you have created a more perfect likable combo?

Lastly, I noticed a unique structural choice that I wanted to discuss, as it’s something Miss Scriptshadow was curious about after the film. Usually, you want your main character to have a big goal once the first act is over. He’s got to kill the terrorists or win the Hunger Games – whatever. Equalizer doesn’t have this. McCall kills the local Russian Mob Ring, and for the next 20-25 minutes, he doesn’t have a clear goal.

He’s sort of drifting between helping people when his help is required. His storyline is directionless. Which can kill a script dead if it goes on for too long. I mean it’s great McCall is helping random people, but sooner or later the audience is going to be like, “Wait, where is this going???” So Wenk does something really clever, and something you should take a cue from. During that 20-25 minutes, he switches the goal over to the villain.

You can do this in your script, when, for whatever reason, your main character’s story is stagnant. Switch the focus over to the villain and his goal, and in this case that means our villain investigating who killed his Russian gang. The story is still moving forward because we feel him getting closer to discovering our buddy, McCall. Once he finds him, the story hits a new beat. McCall has to take these guys down before they take him down, giving both sides an overarching story goal that effortlessly drives the story for the last hour.

There was really only one big thing that bothered me, and it bothered me in the script as well. The Home Depot climax felt too safe. The script was so good up until that point, that to conclude things with a generic cat and mouse game in a glorified warehouse – it was lightweight. Using the tools from his store to defeat the bad guys gave the impression of cleverness, but in reality, we were never at his work, so who cares if he’s using his unique knowledge of his workplace against the bad guys. Plus, McCall can kill people with anything. He doesn’t need tools. The tools ended up being cheap gore.

Because I loved the first 95% of the script so much, I didn’t penalize the script for that ending. Here, in movie form, it was more evident that it didn’t work, which brought it down a notch for me.

With that said, I still think this script is fucking amazing and should be studied in all screenwriting classes and read by all screenwriters. You can see Wenk’s philosophy at work in every scene – always looking to take words out, minimizing anything that’s unnecessary, keeping the read sparse and focused. It’s great stuff.

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Do the actor’s job for him – Like I was saying earlier, Denzel brought the OCD angle to McCall to make him more distinctive. Learn from this as a writer. When you’re writing a character, think about them from the actor’s point of view. Think about what the actor is going to say about your character after they read the script and how they might want to improve him/her. Then, write all that stuff into the character before it gets to the actor. I believe, that if an actor feels like they need to improve their character, that the writer didn’t do his job. You should build all that stuff into the character ahead of time, and you can do this, at least partially, by anticipating the weaknesses an actor might see in the character, and addressing them yourself.

Amateur Offerings is back once again! Check out the scripts below and offer constructive criticism, and then vote for the best of the bunch!

TITLE: Exodus

GENRE: Sci-fi

LOGLINE: The interstellar migration of the human race has failed. On our new planet a widowed construction worker learns of a message from an eccentric journalist on Earth; one that unravels a conspiracy that has crossed light-years – one that puts him firmly in the sights of the government’s most dangerous agents

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: We are two brother’s from the UK with the itch to tell a story. That story has culminated with the labour of love that you have sitting in this email.

Influenced by sci-fi classics such as Blade Runner Exodus is story that crosses light-years, but crucially we feel it remains personal – with its core centred around the human struggle with grief and loss. Onto this grounding we layered all the elements that we look for ourselves from a story – elements such as a genuinely conflicted hero, a three dimensional antagonist and dialogue that doesn’t make you cringe when you read it.

We have had strange anomalies with a previous reviewer, rating it excellent across the board before rejecting it when it entered their competition for grammatical errors.

Undeterred we returned to the drawing board and are hoping to get our voice heard. Take a shot on us two from across the pond, you will not be disappointed.

GENRE: Comedy-Horror

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’ve started a few screenplays before but Dawn was the first one I ever completed. It was the first of the two screenplays I wrote during my year at Vancouver Film School. I managed to option it a week before I graduated. That option has since dried up but I figure if it’s option-worthy then it must be pretty good.

GENRE: Crime/Comedy

LOGLINE: After a robbing a gas station, two small time criminals steals a car with a kidnapped man in the trunk, and has to stay hidden from two rival gangs, while they try to collect money for one of the criminal’s daughter.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Because it’s a fast paced crime comedy with two female leading roles. I wrote it because it’s simply something I’d watch, with characters I’d watch.

GENRE: 3D Family, Adventure

LOGLINE: Having been kidnapped in South Africa, a resilient young traveller is forced into criminal activity by his captors in order to repay the ransom his family could not afford.

Is “The Hangover” one of the best ideas in Hollywood history?

Is “The Hangover” one of the best ideas in Hollywood history?

Are you aware that 90% of all scripts are dead before the writer even writes the first word? Welcome to the “bad idea,” the quickest and most terrifying way to destroy a screenplay. The worst thing about the bad idea is that, after coming up with it, you are beholden to it for the next year, two, three, five. You could spend countless hours and endless rewrites on something that has no chance of success no matter how much you put into it.

Now some might argue that struggling through your bad ideas is part of the learning process. Your bad ideas are where you practice, where you fail, where you grow. You don’t have enough experience yet to know that the idea is weak, so you keep fighting the script, and in the process, learn how to write scenes and characters and dialogue.

But bad ideas are not exclusive to young writers. Anyone can have a bad idea. Animal Kingdom was one of my favorite movies a few years ago. It was raw and fresh and different. I recently watched the director’s newest effort, “The Rover.” As far as I can tell, it’s a dystopian tale about a man who wants his car back. Now we know David Michod can write and direct. We saw it in his previous film. But once he locked himself into that bad idea, there was nothing he could do. The idea wasn’t good enough to sustain a movie.

Now some of you may be saying, “Judging ideas is pointless.” “Whether an idea is good or not is subjective.” That’s sorta true. But I’d argue there are lots of ideas we can all agree on. Take, for example, these two that I just made up…

1) Payback – A famous White Supremacist Leader wakes up in the middle of a gang-infested African-American neighborhood.

2) The Tech – A well-known but reclusive tech blogger wakes up in the middle of Silicon Valley.

Which one of these ideas is better? I’m guessing that we’re all in the same boat here. The first idea knocks the second idea out of the park. Why? Let’s take a closer look at both ideas to find out.

The first thing you notice in Payback’s logline is CONFLICT. There’s a ton of it. A white supremacist in the middle of a predominantly black ghetto tells us there are going to be a number of confrontations, and they aren’t going to be pretty. Next we have stakes. There’s a good chance that our character’s life is in jeopardy. Finally, a good idea inspires the reader to ask questions. “Will he get out of this?” we ask. “What will they do if they catch him?” Questions put the reader in the story before they’ve even read it. If you can put readers in stories they haven’t read yet? You’re doing your job as a writer.

Now let’s check out The Tech. A reclusive tech blogger is dropped inside Silicon Valley. Doesn’t sound like there’s much conflict here, does there? If he’s a tech blogger, he probably knows a lot about Silicon Valley and should have an easy time getting out, right? Also, if he’s reclusive, will people even recognize him? And are those people even on the street? Probably not. This is sounding less and less interesting by the second. Actually, now that I think about it, does he even want to leave? As you can see, when there’s no problem, there’s no reason for the hero to act. So unlike our white supremacist, our blogger might decide to head to Starbucks and grab a coffee. Why not?

So the first lesson in writing a great idea is that there needs to be some sort of problem, and that problem needs to cause some ongoing conflict in the storyline. Stakes are important as well, and should come naturally if you have conflict in place. Alright, let’s see if this holds up with a few of the best ideas ever to grace the silver screen. Notice I’m not saying these are the best movies. Just the best ideas.

Jurassic Park – A group of people are trapped inside an island theme park for cloned dinosaurs.

The Hangover – Three groomsmen must retrace their steps after a black-out drunken night in Vegas to find the missing groom and get him back to his wedding on time.

Hancock – A depressed alcoholic super hero must fight off his inner demons in order to save his city from a rapidly growing crime wave.

Rear Window – A wheelchair bound photographer confined to his apartment starts watching his neighbors and becomes convinced that one of them has committed a murder.

Say what you want about these films. These are all quality movie ideas. And they all fall in line with our “good idea” requirements. A problem is introduced that creates conflict. The stakes are high (except for, arguably, Rear Window). And they get us asking questions (The Hangover and Rear Window, especially.) Now, here are a few amateur loglines I found on the internet for comparison.

Seven-Fourteen (drama) – A psychiatrist during the 1970s finds himself selling prescriptions to a vicious mob boss while being hunted down by an FBI agent.

The Quest For Triaba: Secrets of the Forbidden City – After Lucas and Alexa travel with Mattack to the Forbidden City, Zetra and Connor try to find their own way into the Forbidden City. Along the way, these different groups of survivors meet up with some of the Wasteland’s most hideous people. Can Zetra and Connor make it to the Forbidden City? Can Alexa and Lucas fight off the terrible Carga? What will happen?

Cold Snap (drama/thriller) – During Christmas season – three young, bored and jobless teens hatch a plan to rob a family man’s traditional takeaway shop.

A Mind Reader (Horror) – A serial killer who can read minds is terrorizing Las Vegas. Emma, a troubled young girl is receiving visits from the ghosts of his victims. She seeks solace with a group of young teenage psychics. For differing reasons, they decide to find the mind reader themselves. The only trouble is, it’s hard to stay a step ahead of someone who can read your mind.

Hmm, my theory for good ideas is crumbling as we speak. Three of these ideas do just as our professional loglines did – they introduced a problem. Seven-Fourteen has the FBI hunting our hero down. The Quest for Triaba has the terrible Carga wreaking havoc. A Mind Reader has a serial killer on the loose. The only one that doesn’t have a problem is Cold Snap.

And yet, it’s hard to argue that any of these ideas are any good. If I were pressed for the best idea, I’d probably say Seven-Fourteen. But it still feels weak. In order to figure out what’s not working here, we may need to dissect each idea individually. Maybe then we can add some more rules to our list.

Seven-Fourteen (drama) – Okay, so like I said above, the writer creates a problem here. A psychiatrist is being hunted by an FBI agent. But there’s something very bland about it. FBI agents are in every single movie. What’s so special about this one? Not only that, but the elements don’t come together in a cohesive manner. What do the 70s have to do with this idea? How would it be any different if he were selling prescriptions today? And why would the FBI hunt down a psychiatrist? Isn’t the way more important catch here the mob boss? This idea is missing both excitement and logic.

The Quest For Triaba: Secrets of the Forbidden City – At first glance, this appears to be more of a logline problem than an idea problem. But logline or not, the idea is unfocused. I mean the title is “The Quest for Triaba,” yet there isn’t a single mention of Triaba in the logline. How could that be if Triaba is the goal driving the story? It’s pretty clear to me what isn’t working about this idea. It’s unfocused and confusing.

Cold Snap (drama/thriller) – The problem with Cold Snap as an idea is that there’s no story problem. Our main characters decide to do something because they’re “bored.” Boredom is rarely a good starting point for a story. You want a character who’s in peril, who’s in trouble. That way their motivation is strong. They must act to solve a problem. Also, this idea, like Seven-Fourteen, is too plain. Look at a comparable idea done better, the Sidney Lumet film, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead. “When two brothers organize the ‘perfect crime,’ robbing their parents’ jewelry store, their mom is accidentally killed during the robbery, leading to the implosion of the family.”

A Mind Reader (Horror) – Surely an idea about serial killers who can read minds is good, right? Not really. Whenever you complement strong elements, you want to do so with irony. The Billy Bob Thorton Christmas movie isn’t called “Dolphin-Loving Santa.” It’s called “Bad Santa.” There’s no irony in a Santa who loves dolphins just as there’s no irony in a serial killer who can read minds. Here’s another serial killer idea – A serial killer who only kills serial killers. That’s the premise for Dexter, the HBO show. That’s an idea. “A Mind Reader” is a muddled beginning to an idea that hasn’t been explored enough. Also, once you add ghosts, the idea becomes too crowded.

Okay, so we’ve learned a few new things. An idea works best when it’s big or exciting (as opposed to bland). This seems obvious but I can’t express how often I see this mistake. The addition of irony always makes an idea better. It’s why Hancock was such a big spec sale and huge movie, despite the execution being so lackluster. The idea must be clear. The idea must be focused.

But wait a minute. Not every idea can be Jurassic Park, can it? What about movies that don’t sound good in idea form? Like The Skeleton Twins! Which I loved. The logline for that was, “Two siblings both try (and fail) to commit suicide on the same day, later coming together to try and resolve their complicated relationship.” The “problem” here is their “troubled relationship,” which is hardly the kind of big idea that drives people to theaters. And yet the movie turned out good. How can that happen if it’s not a good idea?

The Skeleton Twins, like a lot of indie movies, is an “execution-dependent” film, which is code for “character-driven.” These scripts are built less on ideas as they are on characters. Once you have strong characters in your script, you attract strong actors. The marketing of the film then focuses on those actors, as opposed to the concept itself. If you watch any publicity material for The Skeleton Twins, it’s all about Kristin Wiig and Bill Hader as opposed to the story. You’ll find that these scripts almost NEVER make it through the spec market because the ideas aren’t big enough. They have to be made on the indie circuit and are usually done by writer-directors.

That doesn’t mean you can’t write character-driven ideas. You just need to come up with good concepts for them. That way you get the best of both worlds. Like 2012’s Safety Not Guaranteed. A man puts an ad in the paper claiming he can time-travel and that he needs help. This is the starting point not for some Edge of Tomorrow knock-off, but an exploration of four characters and the problems holding them back in life.

All of this leads to the big question. What are the definitive traits that make up a good idea? We can never say for sure. But we’ve certainly seen crossover elements in the good ideas. Here are the big ones in list form. By no means must your idea include every item on the list, but it should definitely have a few.

1) There’s a big problem facing your hero(es) (the Nazis are trying to get the Ark of the Covenant to use as a weapon!).

2) There is lots of conflict inherent in the idea (The Walking Dead – everyone’s life is constantly in danger from both zombies and other humans).

3) There are high stakes (Jaws – if they shut down the beach because of the shark attacks, the town won’t make any money during tourist season).

4) There’s something unique/original about your idea (memory zapping in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind).

5) The idea feels big (A town and their fuel is in jeopardy from a rival band of raiders in Mad Max is a much bigger idea than a man who wants his car back in The Rover).

6) There is some irony in the idea (A king who must make an important speech has a catastrophic stuttering problem).

And let it be said that ONLY meeting the bare minimum of this criteria isn’t enough. I wouldn’t create a tiny problem to set your story in motion. I’d find something big. I wouldn’t be okay with a little bit of a conflict. I’d add a lot.

Does this article end the question of “What makes a good idea?” Of course not. Ideas are subjective creatures. What’s appealing to me isn’t always appealing to you. I thought the idea behind Dallas Buyers Club sounded melodramatic and outdated. But others liked it and that’s part of the subjectivity of this business.

With that said, you have a much better chance of creating a good idea if you follow today’s advice. What about you guys? What do you think makes a good idea? And to take that question a step further, how do you come up with your own ideas?