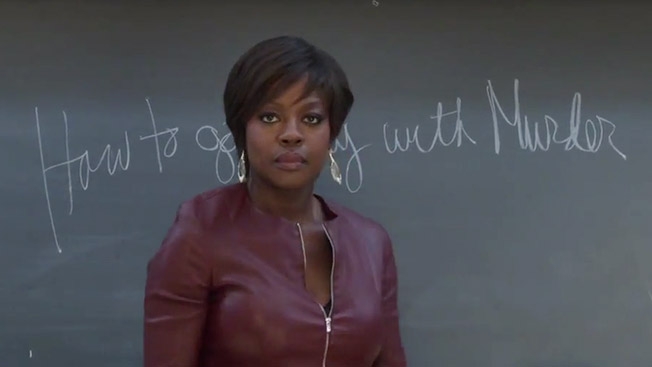

Genre: Procedural

Premise: One of the top lawyers in the country is also a professor who recruits her law students to help her win cases.

About: The new show coming this fall from TV mogul Shonda Rhimes. After going to film school, Rhimes was able to put together a short film in 1998 that starred Jada Pinkett-Smith. She would later sell a spec to New Line, write the Britney Spears film, Crossroads, write the sequel to The Princess Diaries, then a year later, change her life with Grey’s Anatomy. Rhimes is teaming up with longtime collaborator Pete Nowalk, who’s worked with her on Grey’s and Scandal. He wrote the pilot and created the show.

Writer: Pete Nowalk

Details: 63 pages – 12/3/13

When you want to write a hip new unorthodox show about cancer or the apocalypse, go to HBO or AMC. When you want to write a show that everybody in America watches, you go to Shonda Rhimes. This girl has the pulse of America on her fingertips. Whatever the magic TV touch is, she’s got it. And her latest, How to Get Away With Murder, is the most buzzed about network show coming this year.

To be honest, I have no interest in network shows. There’s a reason they’ve been shut out of the Emmys. While everyone else is taking chances, they’re playing it as safe as the medium will allow it. Ongoing storylines are sacrificed in favor of a simplistic procedural style that allows easy entry to latecomers. This results in a nice quick fix after a long day of work, but few rewards for longtime viewers, the ones who keep the show on the map.

But I’ll tell you this. These shows pay their writers well. And since not everyone can spearhead the next Breaking Bad, you writers looking to make a career at this shouldn’t mark these network shows off your list. Especially if you get a shot at working with one of the best network prime-timers in the business, Shonda Rhimes.

How To Get Away With Murder starts the way you’d hope a show with that title would start. Preppy Michaela, sexy Patrick, Boyish Wes, and bookish Laurel, all grad students at Middleton University, each have blood on their hands. No, LITERALLY. They actually have blood on their hands. The four have just murdered someone. But the snippets of dialogue they exchange aren’t telling us the whole story. All we can see is that they’re scared and they don’t agree on what to do next.

Flashback to 4 months ago, when the four enter one of the most prestigious legal classes in the country, Criminal 101, or how their sociopath but highly successful law professor, Annalise DeWitt puts it: “How to Get Away With Murder.”

Annalise, like a lot of Rhimes’s characters, has many dimensions. She’s strong. She’s smart. She’s demanding. She’s calm. She’s cunning. She’s evil. And she has secrets. Oh, does she have secrets. Annalise tells the class that they’re going to be helping her in her latest case, where a woman, Gina, is accused of trying to murder her boss by exchanging his medication with one she knew he was allergic to.

Annalise makes a little game of it. Whoever does the most to help win the case gets her coveted “immunity idol trophy,” (which, of course, later becomes the murder weapon for our students). The trophy allows you to get out of exams and assignments. And it’s implied that whoever gets it first will be the one Annalise mentors this semester.

Each student has their own ideas on how to defend Gina, but Wes is the one we center on most. Wes catches Annalise in bed with someone, gasp, other than her husband, so she places him on Team Annalise to… what? Keep him quiet? Or because he’s actually good? As is usually the case with Annalise, we don’t know.

Over the course of the trial, Wes will learn that Annalise refuses to lose. It doesn’t matter if she has to take down the people she’s closest to. She will ruin lives and threaten others. All in the name of being the best lawyer in the country. The question is, does Wes want to be a part of that, a team that sacrifices their morals to be the best. Or does he want to live that quiet easy legal life without any headaches, the exact life Annalise despises so much? We’ll have to watch to find out.

Man, let me say this. This Nowalk guy knows how to freaking pack a story. There was a TON of stuff going on in How to Get Away With Murder. But not in that bad clumsy way you see in so many amateur scripts. Every piece of information is cleverly set up to be paid off later. Oh, that man Wes accidentally caught Annalise banging? That wasn’t just for shock value. That comes back in the trial.

That’s the thing with “Murder.” Everything is a setup. Which means almost every scene in the second half has a payoff. I really don’t know where to start here because there’s so much good. I mean yeah, it’s cheesy entertainment. There’s nothing that heavy here. Even death is protected by that ABC “everything’s going to be okay” sheen. But it’s all so damn entertaining.

Every character here is memorable. And that doesn’t mean they’re all complex. But Nowalk is really good at setting up who the characters are. He does this cleverly right away actually, by placing Patrick, Michaela, Wes, and Laurel in a messy situation.

If you’ve read Scriptshadow, you know this is one of the best ways to show the reader who your characters are. Put them all in a bad situation, then watch how they react. Patrick is freaking out, Wes is calm, Micaheala can’t make a decision, Laurel is defiant. As with any bad situation, each character will react differently. And it’s that difference that allows us to see who they are.

From there, Nowalk creates a ton of mystery boxes so that we’ve got multiple things to wonder about. It’s like hedging your bets as a writer. If they don’t like this mystery box, they’ll like that one. If not that one, we’ll create another. There are four main ones – who the hell did these students murder and why? There’s a missing girl in the flashback storyline (which I didn’t even have time to get to). We have the case itself (Did Gina do it?). And we have a mysterious girl who lives across from Wes who gets into arguments every night with the former boyfriend of the girl who’s missing.

Then you have Annalise herself. What a great character. Rhimes and Nowalk are really good at this stuff. Annalise is so complex. She gets mad when you think she should be calm (after you just did well in class), or calm when you think she should be mad (after Wes catches her having sex with another man).

But the best part about this character is that Nowalk and Rhimes aren’t taking the easy way out with her. They’re making her just as bad as she is good. In fact, I’d argue that they haven’t shown us any good yet. She’s cheating on her husband. She (spoiler) throws a friend under the bus to save her client, even though she knows her client is guilty. And she’ll break down on a dime to get you to side with her, only to coldly go back to neutral the second you turn away, showing us it was all an act.

I think the thing that most impressed me though was a scene in the middle of the script. It’s a scene that very easily could’ve been spat onto the page, but Nowalk CRAFTS the scene, turns it into something much better than it could’ve been.

It’s a scene where Annalise tells the class that tomorrow, they’ll each have one minute to pitch their angle on how they’d defend Gina. The handful of students who come up with the best defense strategy, she’ll take to court. I want you to think about how you would write this scene. Stop right now and imagine it in your head.

Here’s how the scene was written. First, Nowalk did something smart. The best scenes are usually set up in some way. So we go back a few scenes to set this scene up. Wes had screwed up in class on the first day. Because of this, Annalise told Wes that he’d be pitching last, after all 80 students. And he wouldn’t be allowed to repeat any of the previous suggestions.

This way, when the scene begins, it has form. Why? Because we know Wes is pitching last. This creates both SUSPENSE and TENSION. Suspense because we’re eagerly anticipating Wes’s turn and what he’s going to say. And tension because as each person pitches, Wes has to cross one more idea off his list. At the very end, someone takes his final idea. And Wes has to come up with something on the fly.

I’ve seen the amateur version of this scene before. Bad writers want to shoot straight to the fun stuff, the jump-cutting between each student as they give their defense ideas. The scene has no form because it doesn’t have anything anchoring it (like Wes). Dare I say that it’s predisposed.

How to Get Away With Murder is harmless entertainment. But it’s as good as you’re going to find harmless entertainment. I’ll be trying to get away with murder this September. You should too.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Going back sometimes allows you to go forward. If you’re struggling to write a scene, see if you can go back a scene or two and SET SOMETHING UP which will allow you to write the scene. That’s what Nowalk did here. By going back and setting up that Wes screwed up, it allowed him to create this class scene where Wes is told he’s going last and can’t repeat anyone, which made the scene way more exciting than had it been written straight-up.

What I learned 2: Create dual-jobs for your hero to discover untapped concepts. One thing I realized here is that typically on television shows, a lawyer is a lawyer. That’s all they do. Ditto almost any job. A cop is a cop. A doctor is a doctor. But we live in a world where lots of people have two or more jobs. Under this setup, your characters will have multiple skills and lives. These skills can be combined in unique ways to create untapped show ideas. That’s what happened here. Annalise is a professor and a lawyer. That’s what allowed them to come with this unique premise. Had the writers been thinking too linearly, the way everyone thinks, they would never have stumbled across this unique premise.

Genre: Drama – Real Life

Premise: When a deep-sea drilling station encounters an unexpected series of explosions, the men onboard must scramble for their lives before the whole thing goes down.

About: This is the true story of how the deep-sea drilling rig “Deepwater Horizon” had a blowout that resulted in the largest offshore oil spill in U.S. history. The script was written by relatively unknown writer Matthew Sand, whose sole produced credit is 2009’s “Ninja Assassin.” When the rewrite assignment went out, the producers didn’t tell anyone that a key stipulation was that only writers with the name “Matthew” were allowed on the project. As such, the current rewrite is penned by Matthew Michael Carnahan (World War Z). J.C. Chandor, who directed tiny films Margin Call and All is Lost, is stepping up to the big time with this huge production.

Writer: Matthew Sand, Matthew Michael Carnahan

Details: 115 pages – December 2013 draft

Rarely do I get all world issues’n stuff on Scriptshadow, but today’s script got me thinking. Deepwater Horizon is about dangerous missions that require drilling into the most remote areas on earth, as they’re the last places we’re able to find oil.

Why are we spending so much money on getting oil when we don’t need it anymore? I mean, we need it, of course. But if we put all our focus into 15 hard years of solar, electric, or hydrogen based energy infrastructure, we’d be able to do it.

But we don’t. Why? The only reason I can think of is that oil and fuel are so embedded in our economy, that if we removed them, huge companies would collapse, companies so big that they would take the rest of the economy down with them, basically destroying America.

Is that why we keep oil around? Because our economy isn’t prepared to exist without it? It must be, with alternative energy having so many benefits. We’d have cleaner air, fewer wars, more harmony. I just can’t figure out how a country this technologically advanced couldn’t eliminate oil.

Whoa, that got deep. Speaking of deep, the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig has just dug the furthest into the earth of any drilling rig in history. 35,000 feet. That’s the equivalent of where you’re sitting to an airplane at cruising altitude.

But DH is also 60 days behind schedule. And the suits are flying in to see what the holdup is. They’re accompanied by Comms Officer Mike Williams, who’s about to be promoted to head honcho status on Deepwater.

Mike’s trying to calm the suits down, explaining that when you drill through five miles of ocean water and two miles of rock sediment, not everything goes as planned. The oil’s squeezing upwards, trying to get out of this pocket that it’s been stuck in for the past 2 million years. Eager oil is not good oil.

Once on the Deepwater, we meet all the folks who work with Mike, as well as the intricacies of the rig itself. And we really go all in here. The first 25 pages are dedicated to explaining every little pipe, every little gauge, every little nuance of this thing. It’s a lot to take in.

But the most important piece of equipment is the pressure gauge and specifically, the number 700. That’s the amount of pressure that the Deepwater Horizon can handle. If the pressure of the oil goes above that point, it’s going to blow. And blowing is bad. At least in this instance. So it’s something that has to be constantly monitored.

As you can imagine, the oil eventually hits the fan. The pressure blows past 700 to 900, which is the highest reading on the gauge.

The rest of the script turns into a sort of “Titanic but with raining fire and oil” as everyone tries to escape without their skin melting off their body. Throughout this, we’re intercutting with the bridge of the Deepwater where the safe suits, as you can guess, are more concerned with their billion dollar investment than the safety of the men dying on it. It’s because of this problem that our hero, Mike, may end as a footnote in one of the worst disasters in oil-drilling history.

Deepwater Horizon is like a good book. It’s got a heavy burden of investment. You’re introduced to a ton of characters as well as an exceptionally complicated structure. But if you stick with it, you’re rewarded with a hell of a survival thriller.

As for the opening, it’s not just the description that’s frustrating. It’s that you’re not really sure what’s being described. I don’t know what a “Moon Pool” is. Or what a “Standpipe” looks like inside of a Moon Pool. It’s all just a vague blob in my head, and as those vague blobs began to build up, I found myself increasingly unsure of what I was looking at.

But here’s a good screenplay tip for you. Sand and Carnahan knew that when it came to the most important thing on the ship, which was the drill pressure, they had to make it as simple as possible. An audience that doesn’t understand how the key piece of equipment works is going to miss the point when everything goes to shit.

So the writers created this gauge and they simply said, “THIS CANNOT REACH 700.” We had that number bludgeoned into our head. “700 bad!” And that way, they could play with it, which they did. Every other scene, we’re monitoring that gauge, and we’re seeing “550” or “600.” We’re nervously adjusting in our seats. “Oh man. That’s so close to 700! What if it doesn’t go back down?!”

Where Deepwater really excels, though, is once the oil blows. In screenwriting, the ultimate goal is to give the reader something they’ve never seen before THAT’S ALSO exciting. What I mean by that is, it’s easy to come up with something that nobody’s seen before. You could write a movie about a turtle wedding for all I care – no one’s seen that before. But to give us something new that’s also exciting? That’s really hard. And Deepwater does it.

We’ve never been on an oil rig with exploding engines and mud and fire raining down while running around through a pipe palace of metal and glass projectiles shooting at us from every direction. It just feels different. And that difference makes it exciting.

The only problem with the script is the one I mentioned above. Because we’re not actually seeing this thing, it’s hard to visually comprehend it. Even simple stuff like where one thing was located in geographic comparison to another was hard to understand. Due to that confusion, there are parts of the script that don’t make sense.

For example, we have the “boat” part of the rig. This is where the bridge is, which is where the captain is located (along with all the suits). We keep cutting back to this bridge while all this craziness is going on. But for the majority of the script, these men are totally oblivious to the skyscraper-tall fire spout raining shards of burning oil down on them.

I couldn’t, for the life of me, figure out how you wouldn’t be able to see fire raining down. I mean it’s not like you’re surrounded by a city full of skyscrapers. We’re in the middle of an ocean! You’re the only visual for a thousand miles. Maybe this room was placed in a position where that stuff couldn’t be seen (were they underwater maybe?). But because this information was buried so deep inside all the OTHER information given to us, it was hard to catch.

But outside of that, this was really good. The script does a great job of creating a sense of dread before the blow occurs, and a wonderful job of showing the unique kind of destruction that results after the blow occurred. If done right, this could be one of those surprise Gravity-breakout type hits. Rooting for Chandor to pull it off.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Exposition Allowance. Every writer should give themselves an Exposition Allowance before a script. How much you’ll need will depend on what type of script it is. In scripts like Titanic and Deepwater Horizon, where the intricacies of the environments are a crucial factor in enjoying the movie later on (we’re going to be visiting a lot of these rooms and need to know how they work), it’s okay to have a big allowance. But if you’re writing a boat movie like, say, Life of Pi or Captain Phillips, extensive explanations of the boats aren’t necessary. We don’t need to know what every room looks like. In those cases, keep your exposition allowance low.

Read and vote for your favorite script in the comments. I’m really excited about this week. A long time reader, D, has submitted his script “The Brothers Ternion.” I’ve exchanged e-mails with D for a long time and know he’s a huge student of the craft. So to finally see a script from him is awesome. Excited about the other entries as well. Axiom of Evil, in particular, caught my eye. We even have a script from the past coming back for another look. But this isn’t about me. It’s about you. So get to reading and let me know what you think!

Title: The Brothers Ternion

Genre: Comedy

Logline: Three brothers, long estranged from one another, are reunited by chance in the small town of Mumford.

Who I am: Long time reader, first time submitter

Why you should read: “. . . funny, touching and extremely well written . . . I’ve never read a script in this competition that felt so complete, so much like a movie that was ready to be filmed tomorrow. I can’t say enough good things about this script. It was just a fully realized and brilliant piece of work.” – Nicholl Contest script reader for The Brothers Ternion. This quote was also featured on Nicholl’s Facebook page in May as their daily reader quote. I just found this out now, since they e-mailed reader comments to all current quarterfinalists (like myself) this week.

Why you SHOULD NOT read it: It’s NOT a GSU script (the other Nicholl reader described it as “If Wes Anderson had written Stepbrothers II”).

Title: The Berzerkers

Genre: Action/Thriller/Comedy

Logline: A team of disabled vets reluctantly reunite when their former commander drops a bombshell on them: the terrorist who caused their disabilities is in America to pull off a devastating attack, and they’re the only ones who can stop it.

Why You Should Read It: It’s a 2014 Page Awards Semifialist, a 2014 Creative World Awards Quarterfinalist, and it made the top 15% of 2014 Nicholl fellowships. There’s a wide array of reactions to the script, and I’m really curious at to what the SS readers (and you) will say. As for the script? Action galore, fast-paced, complex female characters, wild twists, dark humor, and a strong theme. Oh, yeah, GSU up the wazoo.

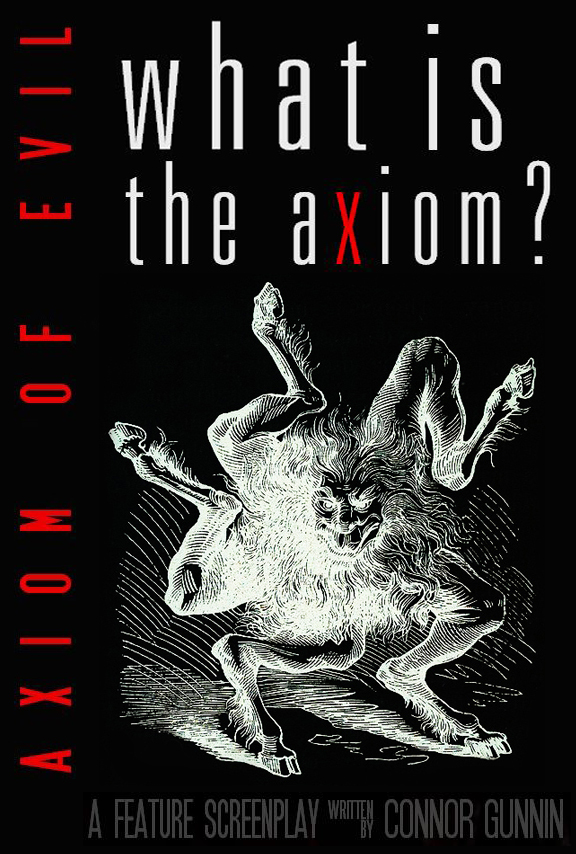

Title: Axiom of Evil

Genre: Horror

Logline: A womanizing psychologist trying to disprove the existence of evil must confront his beliefs when he sleeps with his much younger patient, who may be possessed by a demon.

Why You Should Read: Axiom of Evil differs from typical demonic possession films in that it delves deep into the cerebral aspects of this phenomenon that other films usually neglect. It explores the reasons why possession occurs and illuminates the mind of both the possessed and the demonic. It is a story that seeks to be as intellectually engaging and arousing as it is scary. I have put over a year of research into the subject matter and I am confident that this is a unique and original approach to the exorcism sub-genre.

Length: 112 pages

Title: Misamerica

Logline: Beverly Hills bad girl Abbey Lopez reluctantly rises to teen pop music stardom, while her one hit wonder Mother tries “making it” in the neighborhood by throwing her a million dollar Sweet Sixteen.

Pitch: “Mean Girls” meets “Pitch Perfect” in a musical teen comedy about fame, fortune, and family dysfunction.

Why You Should Read: Like the rest of them I moved to LA with not much more than a script in my back pocket… Three years and nine drafts later I eventually found myself working for a Producer and so broke that my next career move was going to be sleeping in my car. Defeated, I quit the biz and took a job at a local beauty supply store… Selling makeup… Again. — After a year of cleaning off lipsticks (and not writing), I one day found myself helping the mother of the starlet who I had written my screenplay for. I pitched it, she said to email it. A week later I got an call from that starlet’s agent at CAA. — Thanks to that fateful day my script has found her way into the stacks of some great desks, but she needs to keep going… — Carson, my baby’s name is “Misamerica”, I would love for you to meet her.

RETURN SCRIPT!

Title: Sunny Side of Hell

Genre: Action/late era Western

Logline: 1932, Texas – When a farmer’s wife is kidnapped, he races across the dustbowl-ravaged panhandle to save her from being murdered. Up against corrupt cops, the mob, and worst of all, the elements, the only man he can turn to for help is the best friend he betrayed and left for dead ten years prior. Midnight Run by way of Unforgiven.

Why You Should Read: This is the Scriptshadow trifecta right here! Original writer John Eidson had a draft reviewed on Amateur Friday close to a year ago. And the general consensus at that time was: Dude is a helluva writer, now needs to work on becoming a helluva screenwriter… Since then, he has brought on fellow Scriptshadow-ite Patrick Bonner to work in tandem, completely revamping this thing. We have utilized Carson’s original AF review, the Scriptshadow community’s feedback, and then had Carson look at the script independently, to completely tear this thing down and rebuild it as a lean, mean, GSU machine. And it’s really fucking good.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Rom-Com

Premise (from writer): A woman with a rare auditory disorder reconsiders her life of solitude when she meets an inquisitive sound engineer (who might just be crazier than she is). But is his interest in her a case of romance…or research?

Why You Should Read (from writer): Did you love “A Beautiful Mind” with Russell Crowe and Jennifer Connelly? Did you secretly wish it had been more like Russell Crowe’s personal life – i.e. funnier, with less math and more assault charges? — If you answered ‘yes’ to both these questions then please consider casting your eyeballs over my RomCom, The Introvert’s Playlist. I’d be grateful for any and all feedback. I’ve already pledged my first born child to BifferSpice in return for his absolutely incredible notes, but if I wind up having twins you’re all welcome to fight over the other one I guess.

Writer: Rachel Woolley

Details: 94 pages

Rachel Woolly, thank you for making me a happy man. When I opened this and saw 95 pages after a full day of work, I praised you and the Dragon Gods of Screenplay Heaven. If I’d opened a script that was more than 110 pages, I don’t know if I would’ve made it to the end. Never, my screenwriting friends, NEVER underestimate the power of a low page count. It can IMMEDIATELY put the reader on your side.

It’s been a weird last couple of weeks with a shockingly low amount of industry news. Even Comic-Con was light on talk-worthy topics. One thing I’m noticing more and more is that I no longer have a go-to site for movie news. It used to be Deadline Hollywood when Nikki Finke was running the show. But now they’re just copying and pasting press releases to keep their feed going. I thought for sure Finke’s new site was going to fill this gap, but her posting has been scarce to say the least. Why did she even start a new site if she wasn’t going to post on it?

This has left me scrounging for tidbits from multiple sites (THR, Variety, Latino-Review, Slash-Film, First Showing, The Playlist, The Wrap). And still I feel like I’m not getting as much movie news as I desire. More and more, sites are dedicating their time to television, which is great. I cover television on Tuesdays as well. But movie news is still the reason I get up in the morning. I’d be curious to hear where you guys browse around. Maybe the ultimate movie news site is out there. Or maybe there’s an opportunity for somebody new to step up and fill the gap. It might even be you.

Okay, let’s clumsily segue into today’s first Rom-Com script in forever on Scriptshadow. Iris, 29, has a rare hearing disorder where simple noises (breathing, ticking, eating) become extremely loud in her head, to the point where it’s like 17 construction companies all decided to build the world’s tallest skyscraper inside of her brain at once.

Naturally, this has made Iris quite anti-social. In fact, she spends most of her time at home, where she can control the noise. But even that’s becoming difficult, as the next door neighbor’s dog is constantly barking his snout off.

As if God hasn’t made her life difficult enough, Iris gets pulled into Jury Duty for an assault case and must sit in a quiet court room all week where simple noises go to breed. The breathing, the coughing, the hacking, the shifting. It’s like bullet holes to her face.

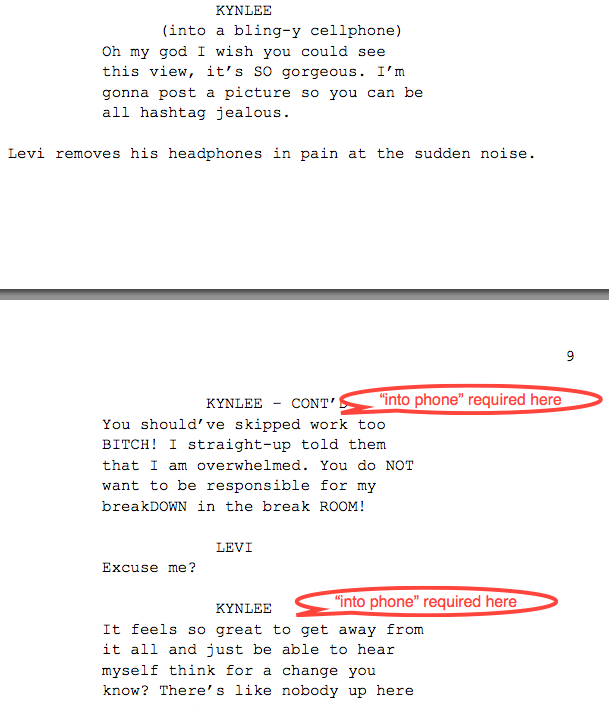

Strangely enough, another audio-obssessed individual happens to be the defendant in the trial. 31 year old Levi is a professional sound recorder who ended up here for supposedly assaulting a ditzy 23 year old who enraged him when she ruined his recording (by taking selfies no less).

Iris is the only one not buying the girl’s story. And after a protracted argument with the other jury members, she finally convinces them to vote Levi innocent. After the trial, Levi finds Iris and wants to thank her for helping him out.

The two get to know each other, and Levi gets a first-class seat on Iris’s insane auditory life. All of Iris’s defense mechanisms are up and she tries to go back to Alonesville so she can live in her safe little bubble again. But wouldn’t you know it, Charming Levi convinces her that love is more important than anything, including annoying breathers.

As I read my way through the first 10 pages of Introvert’s Playlist, I was really impressed. I’d seen some of the comments on the Amateur Offerings post, and while most were praising the writing, many said there were big problems with the story.

Well that wasn’t the story I was reading. The writing here was confident and strong, highlighted with perfect “show don’t tell” scenarios about Iris’s unique disorder (dismantling the waiting room clock at the dentist’s office because it was ticking too loudly). Her writing was also that perfect combination of sparse, yet informative.

But then something happened. A switch was pulled. It’s important for every writer to know when they lose their reader – which story choice broke the suspension of disbelief camel’s back. Because without that knowledge, you can never truly fix your script.

It was page 12 when it happened for me. I had just learned a ton about this unique and intriguing auditory disorder. That alone gave me tons of confidence in the writing because normally when I read a script, the writer’s droning on about something I know EVERYTHING about because I’ve read 20 scripts about the exact same thing over the past month alone. This, however, was new and fresh and different. I was in!

Then we go into this ultra-silly jury case that felt like it was made up on the spot. Having a full 12 member jury for something as insignificant as a simple assault case felt false (especially since it was so clear that the girl was lying). And once that felt false, the introduction of this entire Levi-Iris relationship felt false. And since I had to buy into that relationship in order to buy into the rest of the script, this scene ensured that I wouldn’t get into the rest of the script.

I think writers forget this. That certain scenes in scripts are so critical, that if they don’t work, they ensure dozens of other scenes won’t work either. When you’re setting up your key relationship, even in a comedy, that’s a scene you have to get right. And an overly silly court case isn’t right. There’s no truth to that scene. And when the reader senses a lack of truth, they stop trusting you.

If I were Rachel, this whole court scene is the first thing I’d ditch. Figure out another way for these two to meet each other. Make it more natural. Make it honest. Because this moment is the infrastructure for everything that happens after it. I actually wondered why Rachel didn’t put Iris up in the mountains in place of Assault Girl. This seems like a place Iris would go (to escape the noise) and therefore a more natural place for her to run into Levi.

The other big issue I had was with Iris herself. And I sympathize with Rachel because I know the balancing act she was trying to pull off here. But whatever way you cut it, Iris is equal parts sympathetic and annoying. We feel for her because we know what she’s going through. But it’s kind of like the complainer girl in a group of friends, the one who’s always too cold and she lets you know it? The first time you hear her say it, you feel bad for her. The second time, less so. The third time, it’s a little annoying. The fourth time, really annoying. And after that you just want to strangle her.

There’s a little of that going on here. I feel bad for Iris’s situation, but there were times where I just wanted to say, “Get over it!” Every script has one big balancing act you have to pull off, and I think this is Playlist’s. You have to convince an audience to sympathize with someone who’s annoyed by something no one else finds annoying. Not an easy task.

Now with all that said, there’s some quality writing here and I do see some promise in the story itself. But it needs more truth. I say ditch the over-manufactured court stuff and tell a simpler story about a unique couple. Focus on exploring the characters, not some overcooked plot. I see this as more of an indie film due to the quirkiness of our heroes, so I’d play it more drama-comedy than comedy-drama. Somewhere in the tone of Lake Bell’s “In A World.” That’d be my advice on where to go. I wish Rachel the best of luck. ☺

Script link: The Introvert’s Playlist

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Despite my early rant about page count, page count should always be dictated by story. Several key factors will play a hand in whether your script should top out at 90 pages or 120 pages. The main two are genre and character. Fast and loose genres like Thrillers and Comedies will be around 100 pages. Thicker and more introspective genres like Period Pieces, Real Life Drama or book adaptations, can easily top out at 120. If your story has a high character count (Zero Dark 30), you’re going to need more room to fit them all in. And if you’re doing some major character exploration and/or character development (Silver Linings Playbook), you’re going to also need more pages. Then there are the miscellaneous things. Big world-building stuff (Guradians of the Galaxy) will need space, as will really elaborate plots (Burn After Reading, American Hustle). In the end, take in all this information and figure out if you need a lot of space to tell your story or not that much. Be honest with yourself, give yourself a page goal ahead of time, then try to hit it.

What I learned 2: Always put “INTO PHONE” (or “ON PHONE”) in parentheticals when a character is on the phone. Not just the first time they speak but on all of their phone dialogue lines. This is ESPECIALLY important if you’re intercutting a conversation with a third party. That’s where things start getting confusing for the reader. When Kynlee was on her phone AND having a separate conversation with Levi, I wasn’t clear who she was talking to. Here’s the first part of the exchange in question.

I recently read a script from a beginner scribe that wasn’t very good. The key problem was the plot, which was too simplistic and predictable. This simplicity bled into the scene-writing, which was also too predictable. Everything had an “obvious” quality to it, like the writer hadn’t considered any other possibilities. Frustrated, I shared the experience with Miss Scriptshadow, and we got to talking about it.

We came to an agreement that the reason the plot was so simplistic was because the writer wasn’t being discerning. He wasn’t thinking about what he was writing. He was just writing. This is both the blessing and the curse of being a beginner. A blessing because having no filter means total and utter euphoria when you write. Everything feels wonderful because you never have to think beyond your first inclination. And if it feels that good, then the writing must be good, right?

It isn’t until you’ve written a few scripts that you realize there are choices involved in writing – that it’s okay to stop and think about what you’re going to do before you do it. Because the curse side of never considering options is that your script reads option-less. The plot is either simply boring or simply messy, but it’s always simple.

Here’s the crazy thing though. I was reading another script later in the week – a professional script – and I was encountering the same problem. Not as frequently as with the beginning writer, but it was happening every fifth scene or so. I realized that it’s not just beginners who are guilty of this. The best writers in the world do it as well. It’s a slightly different variation of the practice, but it’s essentially the same thing. I call it: “Predisposed Writing.”

Predisposed Writing is when you go into a situation – usually a scene – knowing what you’re going to write beforehand. This may seem like a good thing. If you already know what you’re going to write, then it must be a good scene! What other explanation could there be for being so certain about something?

But if you already know what you’re going to write, chances are the reader’s going to know what you’re going to write as well. That means you’re writing a scene that they’ve already imagined. And if that happens, you’re boring them. Readers (and audience members) can be sympathetic to this for a scene or two. But if it keeps happening, boredom sets in, and they officially check out.

I’m not saying that your first inclination for a scene is always wrong. It may actually be brilliant. But you owe to yourself to STOP before you write a scene and think about other options. Chances are, there’s something better in the cupboard.

Let’s try to look at this visually. I want you to pretend that you’re an interior designer and imagine you’ve just walked into an empty room, a room which you’ll be designing.

A bad (or beginning) interior designer is going to go into this room with a predisposed point-of-view. They know what a basic room looks like. So that’s what they’re going to give the client. A TV near the corner by the cable outlet. We’ll throw the couch back against the wall. Maybe a vase by the TV to make it look nicer. A lamp or two. In your head, you’re imagining this is going to look pretty killer. Then, when you put it together, you get something like this…

Now you’re looking at this room and probably saying, “Oh my GOD. I would kill myself if I had to live in that space!” Well folks, you’re looking at the visual equivalent of 90% of the scenes I read in amateur screenplays. They’re that dull, that lifeless, that devoid of creativity, and it boils down to writers being too set in their ways.

A good interior designer’s first step is to let their initial inclinations wash over them. Not ignore them. They may still use them. But first they want to explore some not-so-obvious choices. Maybe a nontraditional couch as the centerpiece. A cowhide rug instead of a boring hardwood floor. How does the light come in from the windows? Is there any way to arrange the room to accentuate that? With this approach, you’re more likely to get something like this…

Notice how much more thought was put into this room. Notice how they went with a hardwood floor AND a rug. Look at how the rug is shaped. Look at how funky the couch is. Look at the unique shelves placed on the wall. The other designer didn’t even put shelves on the wall. This room is infinitely nicer than the one above.

Now I can already hear some of you crying foul. “That’s cheating, Carson. The second room has a floor-to-ceiling window and costs a hundred times as much to furnish.” I admit that the analogy breaks down a little in that sense, but not really. With writing, the only currency is time. You have no budgetary considerations. If you take the time to challenge yourself and flesh out your ideas, you can create windows with the most beautiful views in the world. You can put a 20,000 dollar couch in your room. You can change the walls to brick. An imagination is infinite, and when you predispose your writing, you prevent yourself from mining all those possibilities.

Predisposed Writing is not just a scene thing. Writers come in with predisposed characters. They come in with predisposed relationships. They come in with predisposed concepts. The thing to remember with writing, especially screenwriting, is that nothing is set in stone. You can have an idea for something, but once you’re tasked with putting that “something” down on paper, it’s your job to challenge it. Your mind, more or less, has been trained by society to think and act like other minds. Which means most of what you come up with is the same kind of stuff other people come up with. Going against your predisposition, then, is the only surefire way to provide a unique experience for the audience.

Let’s apply this practice to an actual scene, shall we? Let’s say we’re going to write one of the more common scenes in screenwriting, a cop arresting someone, let’s say a drug dealer. Now you’re probably already imagining how this scene is going to play out, right?

My predisposed version has a sketchy dealer on a street corner in a bad neighborhood, dealing dope to some loser. Our officers pull up their car, pop out. The Dealer ushers the buyer away, turns to our officers as they’re approaching, an innocent smile at the ready. Looks like this isn’t the first time they’ve met. There’ll be some funny “we’ve been through this before” banter between the three. But the Dealer senses that something’s off, that they might actually arrest him this time. He decides to make a run for it. They chase him down. Catch him. Scene over.

Hmm, how many times have we seen that before? It might as well be in the Predisposed Hall of Fame. So let’s see what happens when we spend some time considering other options. Again, there’s no law that says you have to write these options into your script. All you’re doing is considering them.

A dope dealer in a bad neighborhood is cliché, right? So what if we made our dealer a… grand piano salesman who deals dope on the side? Our cops have evidence he’s dealing so they go to the piano store to arrest him. Inside, a child prodigy is loudly playing Beethoven’s 9th on a nearby piano. Our cops attempt to ask the salesman a few questions (or read him his Miranda Rights), but the annoying prodigy is playing louder and louder (secretly cued by the salesman?), resulting in a lot of “I’m sorry, I can’t hear yous.” In a moment of distraction, the salesman slams the piano flap down on one of the cop’s hands and makes a run for it. The prodigy breaks into some chase music.

This may or may not be the best scene ever. I’d certainly want to take it through a few more drafts, but it’s more inventive and less cliché than the previous scene.

Now obviously I’m writing with free rein here. Within the context of your story, your dealer may have to be on the street. That’s fine. Then you simply ask what other ways you can make the scene different. Maybe the dealer only speaks Spanish, creating a translation problem. Maybe the dealer’s the brother of one of the cops, complicating the arrest. The options are limitless, but they’re only there if you search for them.

In closing, all I ask is that you not get wrapped up in any predisposed notions when you write. Always consider other possibilities. I promise you that if you perfect this practice, you’ll become a much better screenwriter.