Search Results for: F word

The longer I do this, the more convinced I become that the “in the moment” story is more important than the overall story. What do I mean by that? As long as the story going on in the current scene is entertaining, you’re going to keep the reader hooked. Because if I’m entertained by the first scene and then I’m entertained by the second scene and then I’m entertained by the third scene, and so on and so forth, I’m going to want to keep turning the pages until the script is done.

However, if the individual scenes are hit or miss (I’m entertained by the first scene, I’m bored by the second scene, I’m kinda entertained by the third scene, I’m bored again by the fourth scene) it won’t matter how good the overall story is. Because the pieces within that story are struggling to keep my attention. And as anyone who’s read scripts knows, we don’t finish reading scripts like that.

This begs the question, how do you make each and every scene entertaining? Who out there has the ability to write a good scene EVERY TIME OUT? Isn’t that an impossible standard to live up to? If you’re going by the odds, some of your scenes have to be bad. Right?

Wrong.

This is a toxic way to think.

While it’s true that not every scene can be great – even scenes from some of our favorite movies suck – there’s a method you can use to ensure that your scenes will rarely, if ever, be bad. And by using this method, your likelihood of writing a good scene goes up exponentially.

The method I’m talking about is built around the idea of CONFLICT.

Now we’ve been told ad infinitum that our scenes need conflict. The problem with this advice is that that word is vague and unhelpful when you’re constructing a scene out of thin air. So I’m going to help you see conflict in a new way. And this way should help your scene-writing dramatically.

From now on, I want you to look at every scene as requiring a POSITIVE CHARGE and a NEGATIVE CHARGE. If you live by this simple rule, every scene you write is going to have conflict. Conflict, of course, naturally results in drama. And drama is the magical component that ENTERTAINS audiences.

Let’s look at the simplest version of this – positive character, negative character.

If you watch a movie like Fury Road, you have lots of scenes with your positive charge character, Furiosa – she’s trying to save a group of people – going up against your negative charge character, Mad Max – who’s trying to escape. Every scene between these two characters is entertaining because those opposing charges are always on display.

This is a great way to ensure that most of your scenes will be entertaining. You simply take the two characters who are going to be around each other the most in your movie and you assign one of them a permanent positive charge and the other a permanent negative charge. This guarantees that every scene these two are in is going to have some level of conflict, which is why the scene will probably be good.

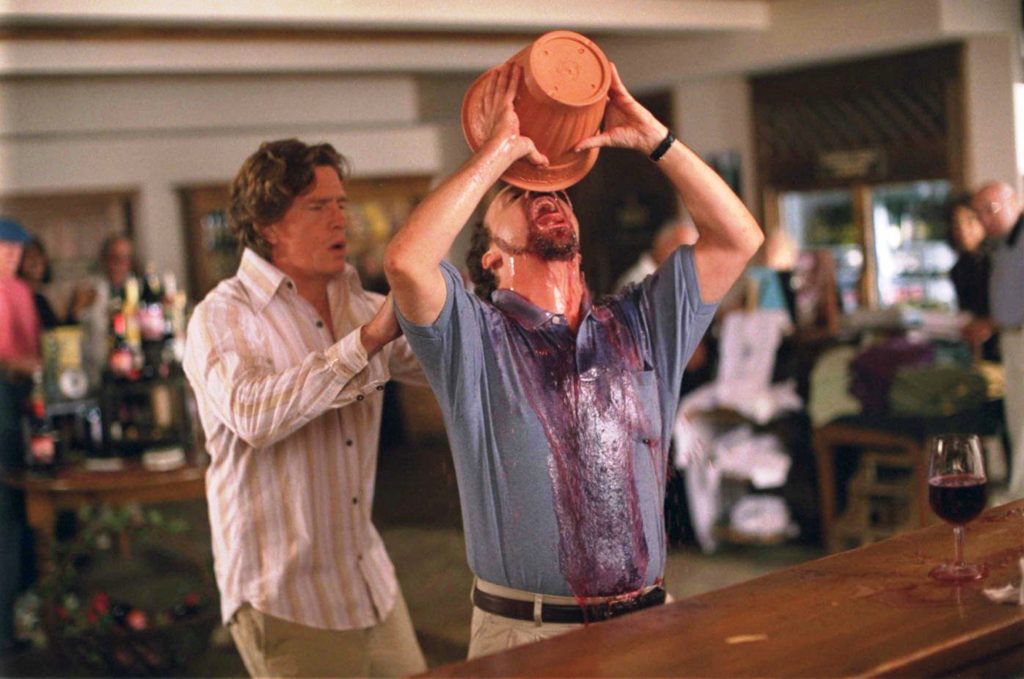

This can work especially well if your narrative is purposefully flat. A great example of this would be the movie Sideways, which follows two friends up to Napa Valley for the weekend. It’s not a plot movie by any means. But the two friends were Jack (positive charge) and Miles (negative charge). Their essence as humans was so embedded in that positive or negative belief system that they didn’t need plot to be entertaining. They just needed to be around each other.

Unfortunately, not all of us are interested in writing buddy cop movies or road trip movies. Which puts you in a more difficult position. Because now instead of the positive and negative charges automatically being there for you in every scene, each scene requires you to find a new positive and negative charge.

This is where screenwriting gets tough. Because each scene becomes a unique challenge to find the charges. And if you’re lazy, you won’t bother doing so. But luckily you have me and I can give you some direction. The second type of positive-negative charge is TEMPORARY CHARGES.

In this scenario, your characters may or may not be carrying permanent positive or negative charges, which means the scene itself must be constructed in a way to give each character in the scene a positive and negative charge.

The most obvious example of this is Character A is mad at Character B about something and lets them have it. Character A is our negative charge (he’s mad!). Character B is our positive charge (he’s trying to defend himself and calm A down). To be clear, Character A may be a positive person throughout the rest of the script, but right now he’s mad, so he becomes the negative charge for the scene. That’s the thing with temporary charges. You can construct them for the moment. They don’t need to be attached to the character’s permanent identity if the scenario calls for it.

But anger isn’t the only negative charge in your Charge Arsenal. I recently watched a movie called Red Rocket. A great film. It’s going to be one of my favorite films of the year. It’s about a former porn star, Mikey, who moves back to his Texas hometown with no money. One of the early scenes has him going to Leondria, a drug dealer, to see if he can sell weed for her.

This is a very simple example of a temporary positive charge temporary negative charge scene. Mikey is the positive charge. He’s trying to get something to better his life – make money so he can move back to Los Angeles. And Leondria is the negative charge. She’s suspicious of Mikey. She’s also potentially dangerous. She doesn’t really want him selling for her. That’s what makes the scene entertaining, is the positive charge being forced to interact with the negative charge.

And by the way, if you want to see a masterclass in positive-negative charges, go watch Fargo (the film). The reason almost every scene in that movie is a classic is because that’s all the Coens focused on back then, was positive and negative charges.

Okay, let’s get a little more nuanced now. Let’s say that you have two characters who get along. Which means, in the majority of their scenes together, they’re both going to be positive charges. This will usually happen when two characters fall in love. So now what? How do we create conflict if two people are on the same page?

Simple. We introduce a negative charge EXTERNALLY. Romeo and Juliet is the perfect example of this. Romeo and Juliet are both positive charges. But their families are both negative charges. Which means you just have to bring a family member (negative charge) into a scene to create conflict. Or, in some cases, just the threat of Romeo and Juliet being caught out with each other can be a negative charge. Think about it. These two aren’t hanging out without a care in the world. They’re hanging out always having to look over their shoulders. Why? Because behind their shoulders is that looming negative charge.

This is what James Cameron did with Titanic as well. At first, Jack and Rose were opposing charges. He was positive (trying to get her) and she was negative (she was resisting). But once they got together, they both became positive. And that meant Cameron had to create a series of external negative charges to keep their scenes entertaining. He did this with Cal Hockley, Rose’s fiancé. He did this with Hockley’s undertaker assistant, who chased them around. And he eventually did it with the ship itself – the sinking and all the problems it created were the primary negative charge in many of their scenes.

Now here’s a question for you. What if you only have one character in a scene and he’s not in a scenario where he’s opposite a negative charge? How do you create the necessary conflict to ensure an entertaining experience for the viewer? This is where writing gets fun. You create the charge FROM WITHIN. One charge will be the external and the other charge will be the internal.

So let’s take a look at Arthur Fleck, the Joker. The reason that Arthur looking in a mirror can be a compelling scene all on its own is because externally he’s struggling to be happy (negative charge). Yet internally, he’s desperate to be happy (positive charge). Which is why he’s shoving his fingers into the sides of his mouth and forcing them up. He wants to smile but he can’t.

If the Joker were to smile and there was no resistance at all, there’d be no conflict. So the scene wouldn’t be dramatic. Hence, the importance of opposing charges.

All of this boils down to when you’re in a scene, ask yourself, where is the positive charge coming from and where is the negative charge coming from? If you have that in place, there’s a good chance you’ll write an entertaining scene. The reason I say “good chance” and not “guaranteed” is because screenwriting is composed of too many variables that affect each scene.

Take a look at the Obi-Wan Kenobi show. Many of the scenes in the second episode followed the rules I laid out above. They have Obi-Wan in them, our positive charge (he’s rescuing Baby Leia), and Baby Leia, who represents our negative charge (she resists his help and is not thankful). These scenes should work according to me. Both characters have an inherent opposing charge. Why, then, do the scenes suck? They suck because Baby Leia is a poorly written character. We don’t like her. We don’t want to be around her. Even the most well-constructed version of conflict in a scene will fail if we don’t like (or are interested in, or care about) one of the characters in the scene.

So obviously, other parts of your screenplay need to be on point. But at least now you know that if you inject that positive and negative charge into every scene, there’s a good chance you’ll write a dramatic scene. And since drama equates to entertainment, we’re going to be invested in each and every one of your scenes. Go forth and try this in your current script and watch how much better your scenes get.

Is this JJ Abram’s big return to prominence? Or is it a five car pile-up waiting to happen?

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: After losing his older brother in a fatal racing wreck, a just out of high school Speed Racer attempts to pick up where his bro left off.

About: As Mr. Crawford informed me, this 1994 draft was intended to be directed by Julien Temple, with a pre-Amber Heard Johnny Depp starring. It was deemed too expensive to produce. Alfonso Cuaron was attached to direct in 1997 but that didn’t work either. The Wachowskis would develop a different script and shoot that back in 2005. The movie did not do well and Speed Racer was quickly forgotten. But JJ never let go of his love for the property and has decided almost 30 years later to turn it into a TV show for Apple. What’s his vision for that show? I assume it’s something akin to his feature treatment, which we’re going to look at today.

Writer: JJ Abrams

Details: 126 pages

I am so torn by what I’m about to experience.

I love JJ.

I hate anime.

JJ. Anime. Anime. JJ.

Even as a kid, when you have zero storytelling discernment – if it’s flashing colors, you’re happy – even as a KID I watched this show and thought it was nonsensical. You can’t turn something nonsensical into a movie and expect good things. You need a base. You need a story. To this day, Speed Racer will be known as the movie that officially slammed the coffin shut on the Wachowskis being considered serious filmmakers.

Is JJ about to make that same mistake? Or has he cracked the code for making live-action anime actually good?

The year is the 50s. We watch as a young man named Rex Racer is racing in a high-stakes race where the tracks are long and weird and have jumps over mountains and stuff. During a particularly difficult section of the track, Rex crashes and DIES! The entire Racer family, including his younger brother Speed, are devastated.

Cut to 12 years later and Speed is now 18. All he wants to do is race but his family is still so devastated by Rex’s death that they don’t even talk about racing. Speed graduates high school and watches, longingly, as his crush, Trixie, heads to London to enter into helicopter school.

Speed finally gets the courage to ask his father if he can race because racing is in his blood and his father shocks him when he takes him to a remote garage and introduces him to the car he’s been building over the last decade. The Mach 5!!! Speed is so excited that he wants to race this weekend. But you haven’t even practiced, his father says. Speed proves that he can handle professional racing by easily beating the lap record at the local speedway.

Just as he’s about to race, he’s cornered by the mysterious Racer-X, who always wears a tinted visor. Racer-X says to him, “Don’t race,” in a very sinister manner. But Speed doesn’t listen, races, and finishes second to Racer-X, which turns him into an overnight superstar, due in no small part to being the younger brother of the deceased Rex.

The next race is a big one and it’s in England! Which means, guess what? He’s going to see Trixie! Except now that he’s a big popular racer, all the women want him, including the seductive Tatiana, who puts all her cards on the table and says she wants to “get naked” with him ASAP.

During the race, Speed realizes that the big time is a lot bigger than he thought. The race is way tougher. And during it, out of nowhere, a giant tree lands in the middle of the speedway and Speed crashes and his car catches fire. To everyone’s shock, Racer-X slams to a stop and runs over to save Speed (BIG SPOILER). When he lifts his helmet momentarily, it’s revealed that Racer-X is actually…. REX! His brother!

But how can this be!?? Later that night, Rex secretly informs Speed that there are higher powers fixing these races, which is why he tried to warn him off them. If you don’t play by the rules, they make you disappear. Is Speed going to give up? Or is he going to keep racing? Something tells me you can’t keep Speedy in the corner. And that both him and his brother are going to rule the racing world together!

Word on the street is that the development process for this project has been agonizingly slow. And I can see why. There are certain tones that have virtually no wiggle room. When you have, say, a romantic comedy, you can develop something that’s goofy, like The Lost City, or romantic, like Love Actually.

But with this… you need to nail a very specific type of humor along with porting what was meant to be animation into live-action, which is a whole other ball of wax that requires an adjustment so sensitive, it’s like trying to land a 747 on a runway the width of a balance beam.

Look no further than Cowboy Bebop to see how quickly things can go south.

With that said, JJ wins again.

This isn’t a great script. But what JJ is really good at, at least as a screenwriter, is telling a simple story well. Which is the foundation of screenwriting. You’re not trying to tell a complex story well. But a simple story. Which is what this is. It’s a kid whose brother died racing but he still wants to be a racer. And that’s it. He races and the races are all fun because they have a bunch of fun wacky car setups.

However, I understand that saying, “He tells a story well” is a vague statement that helps no one. So let me give you an example of what I mean. At the beginning of the second act, Speed reveals to his father that he dreams of being a race car driver, like his brother. So his father gives him his first racing car. Speed then says, “I want to race in the big race this weekend.”

Now most screenwriters would’ve just cut to the race. That’s what this movie is about right? A guy who’s a racer. Let’s put him in races! But the smart screenwriter understands that it doesn’t make a lot of sense for someone to race when they’ve never even practiced before. In these scenarios, YOU MUST MAKE YOUR HERO EARN IT.

So Speed says to his dad, if I can beat the lap record at the local speedway, can I race? And his dad says sure because, “that’s impossible.” Of course, Speed Racer does the impossible and sets the record. This is standard good storytelling. You can’t hand your hero anything. Make them earn it. Especially if they’re making a big leap in the script.

I also liked the big twist (SPOILERS FOLLOW). I’m not familiar with the Speed Racer show so I don’t know if this was JJ’s idea or not. But I loved that Racer-X turned out to be the dead brother. That moment jolted me out of an appreciate reading malaise and turned the script into something I actually wanted to finish.

Because now I could tell the writer actually cared. They thought about the story. Most writers will just kill off the brother in that opening scene to create sympathy. They don’t think beyond: I NEED TO MAKE MY HERO SYMPATHETIC. To bring that storyline back in a powerful way conveys a way higher desire to tell an enjoyable story.

I think I have a better idea of Speed Racer after this script. I always thought of it is as random weird anime. But now I realize it’s like the car version of Inspector Gadget. The cars can do all these fun things and there’s this deeper sci-fi spy story involved. It’s still going to be a hell of a tightrope to walk tone-wise. But if JJ is heavily involved and doesn’t leave it to one of these dime-a-dozen showrunners, I think it might actually be good. And that’s something I was not expecting to say going into this review.

Screenplay Link: Speed Racer

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The correction of “who” to “whom” is used in a dialogue scene in Speed Racer. You know what? Never use the word “whom.” Between the years 1993 and 1999, everybody was obsessed with the difference between the word “who” and “whom.” It became such an obsession that it began appearing in numerous movie dialogues, including films as big as The Phantom Menace. To this day, these silly debates have rattled, mobilized, and confused people to feel passionately about this debate yet I am here to tell you that “whom” is a stupid word that nobody who isn’t trying to sound pretentious uses and you can literally use “who” in its place every time and no one will care. I’m glad we can all agree on this.

This mission is much easier than you’ve been led to believe.

This mission is much easier than you’ve been led to believe.

We spend an awful lot of time on this site, and in the screenwriting community in general, discussing how difficult screenwriting is. And while it’s important to educate ourselves on the challenges of the craft, you don’t want to get too caught up in the roadblocks preventing us from writing a great screenplay. Us humans are notorious for using the negative aspects of our pursuits to justify not pursuing them.

It’s easy to say, “Well only 1 in a million scripts ever gets made so what’s the point?” And if you take a statement like that at face value, then sure, screenwriting does suck. But that statistic includes the 900,000 screenwriters a year who’ve only ever written one screenplay. The people who read this site are way ahead of anybody who’s only written one screenplay, trust me.

And to be honest, I don’t think there are nearly as many screenplays out there as people think there are. The biggest screenplay contest in the world gets 7000 entries (the Nicholl). And a good portion of those are from writers who entered two scripts. I’m just not convinced that there are that many screenplays to compete with. At least not many scripts from writers who actually put blood, sweat, and tears into the pursuit.

Which is the theme of today’s post.

Screenwriting is easy.

Or, at least, easier than you think.

The perception of any pursuit is influenced by the lens you choose to see it through. Therefore, it is in your best interest to frame things positively rather than negatively. For example, you can say, “It’s impossible to get anybody of influence to read my script.” Or you can say, “It’s 100 times easier to get people of influence to read my script today than it was 20 years ago.”

I remember I actually had to COLD CALL agents to try and convince them to read my script. Think about that for a second. And they didn’t even have managers back then. So you only had half the influential people on the representation side to help. Now you have agents AND managers. You can find most of their e-mails on imdb pro. And you can cold e-mail them with way more efficient and successful results. Don’t even get me started on the perils and expenses of printing hard copies of screenplays and then physically sending them to agencies. You guys should thank your lucky stars that you don’t have to deal with that never-ending sh#tshow.

Also, how many freaking TV shows come out a year? 1000? Back when I was coming up it was like 50. All these shows need writers. You are a writer. The opportunities are so much bigger today than they used to be.

As far as writing screenplays, you can see it as an endless list of beat sheets and writing tools you have to use and writing pitfalls you have to avoid and save the cat scenes and midpoint twists and dramatic irony and dialogue with subtext and, oh my god, make sure your voice is strong… whatever that means.

Or you can see it for what it actually is.

Which is telling a story.

That crazy thing that happened to you that one night in college? That story you love to tell when you’re around a bunch of friends sharing their own crazy stories? That’s all a screenplay is. It’s that. There’s a main character (in this case, you). Something happens to throw him into disarray. He now has to achieve something. A bunch of obstacles are thrown in the way. And then he somehow, against all odds, succeeds in the end.

Treat your script like that. Like you’re telling a real-life story. Then spread out the most exciting moments so that they’re evenly spaced over 100 pages. Then make sure your hero is actively pushing towards his goal in between those exciting moments. No need to overcomplicate it.

By the way, screenwriting is the least demanding art there is. You don’t need to buy anything. You don’t need extra people around. You’re not limited to doing it at a certain time of the day. You can write whenever. I am recalling, in this moment, that Scriptshadow writer who wrote a script ON HIS PHONE while riding the train every day to work.

In all honesty, it felt like a script that had been written on a phone. But the point is, you can write anywhere at any time.

Consider what a director has to do. He has to rent all this expensive equipment and find people to help him. And if he wants to shoot anywhere other than his apartment, he has to get filming permits. And if he wants to do anything even remotely cool, like pull focus, he has to hire an additional person and laboriously prep the shot.

You just have to type FADE IN and then whatever comes to mind.

Oh, and by the way, 90% of the screenwriting page is white. Talk about a forgiving medium. You don’t have to come up with these long thoughtful interesting inner monologues from your main character like novelists do. You just tell us what happens. And, when you’re not telling us what happens, you write dialogue – which, oh yeah, takes you all of three minutes per page when you’re on a roll. If that isn’t easy, I don’t know what is.

I write 1500 words a day here on Scriptshadow. At that rate, I could finish a script in 15 days. 15 DAYS! That could be you. Just match my output here on Scriptshadow and you’re celebrating a new script in less than a month.

But wait. Is writing a script really that easy?

Yeah, it kinda is.

- Spend a week coming up with concepts, pick the best one.

- Center your story around a character with a flaw that’s holding him back in life.

- Come up with 2-5 other characters in your hero’s life he has some unresolved issues with, usually his family.

- Introduce a giant problem in your hero’s life.

- This forces them to pursue a goal.

- Come up with a series of obstacles, both big and small, that get in the way of your hero’s goal.

- Have your hero struggle against his flaw as well as with the people in his life, who he can’t fully connect with until he overcomes his flaw.

- Introduce a few unexpected plot beats that both surprise the audience and add excitement to your story.

- Have your hero seemingly fail, maybe even give up.

- Have them regroup and, in your climax, go up against the antagonist to achieve the goal, at which point they will win or lose, and also finally overcome their flaw.

Doesn’t sound too difficult to me.

Once the script is finished, a lot of writers think, “What do I do now?” So I’ll remind you. You have more avenues to get recognized now that at any other point in history. You have no idea how much a screenwriter felt like an outsider before the Internet. Talk about a true helpless feeling. Back then, the only advice anyone could give to you was, find someone who’s in the industry and get them to read your script.

A lot of good that strategy’s going to do if you live in Germany.

These days, getting repped or getting optioned isn’t hard work. It’s just busy work.

It’s going through all the contests you’re considering entering and picking the ones that are right for your script. It’s going to IMDB Pro and getting e-mail addresses for all the agents and managers and production companies your script seems right for and writing up a simple but compelling e-mail query that highlights your irresistible logline (I consult on e-mail queries for $50 if you want outside help- carsonreeves1@gmail.com).

And then it’s sending your script out to the people who request it. After that, you’ve done all you can for that script. You can be proud of yourself and even if you only get no’s, chances are you’re going to gain a few fans who tell you to send any future scripts into them as well.

If you’re still on one of your first three scripts, you might not get any love yet. That’s okay. Keep at it. You just need to figure out a few of the idiosyncrasies of screenwriting and you’ll be well on your way soon.

The process of screenwriting and getting an agent and getting on the Black List and selling your script and getting your script made – they all seem impossible when you look at them through a macro lens. It feels like there are too opportunities for something bad to happen. Instead of that, just focus on the step in front of you.

That might mean coming up with an interesting main character. Or deciding which contests to send your script to. When you do that, things will feel much easier.

There’s way too much negativity out there. It’s like an evil fog that seduces you. It can provide you with a warm feeling to believe that nothing you do matters and it’s all luck.

I’m all for the occasional pity party. It can be an emotional catharsis that’s required to get back on the horse. But, overall, you should be thinking positively. It’s all in how you frame it. Think about how easy screenwriting is compared to other arts. How much easier it is to write professionally today than it was 20 years ago.

By focusing on the good, you’ll be more driven to write. You’ll feel more like your writing matters. And you’ll be more positive when you pitch people, which in turn will make them more interested in you.

So keep writing everyone. It’s actually quite easy.

I’ve got a 2500 word Obi-Wan Kenobi review. Yes, I talk all about Baby Leia, Reva, eopies, and the dangers of Dave Filoni having too much creative control over the Star Wars universe. I also dive into the biggest trailer release month of the decade, breaking down Thor, Gray Man, Mission Impossible, She-Hulk, Andor, and more. I also take a trip into the past to see why A New Hope is so much better than the Star Wars content being released today. I come up with some amazing revelations that surprised even me. We’re talking stuff that would turbo-charge the screenwriting world if writers went back to doing it.

If you would like to read my newsletter, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and I’ll send it your way.

P.S. There is no post Monday because it’s Memorial Day here in the U.S. (a big holiday). But I’ll have a Top Gun Maverick review for you on Tuesday. See ya then!

A quick note: I will be reviewing the “Kenobi” pilot in this month’s newsletter, which is coming out Saturday. So if you’re not already signed up, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER.” :)

You know those lightbulb moments you’ve had that literally changed the way you looked at life? Like when you realized you could go to the bathroom without telling your parents? Or that instead of having to eat at the Commons in college, you could order McDonald’s and pizza every night?

Okay, maybe those are less major revelations than they are my issues with authority. However, when it comes to screenwriting, I’ve had some MAJOR earth-shattering realizations over the years, lightbulb moments that spun my prior views about the craft on their head and totally reinvented the way I approached screenwriting.

Today I thought I’d share these with you so that you could have these epiphanies earlier than I did, and therefore improve at a faster pace. Granted, we all look at the craft differently and are inspired by different things. But hopefully these revelations will help out in some way.

It’s not about you, it’s about the reader – I shudder at the thought of my early screenplays as I was so self-indulgent, I bordered on narcissistic. I still remember handing off a 135 page screenplay to a friend who was a reader at a big production company and them saying to me “Are you sure you don’t want to cut this down? 135 pages is a lot.” I mentally rolled my eyes at my friend due to what a stupid statement this was. A good story doesn’t have a page limit, I wanted to say to her. I was shocked when nothing happened with the script and figured that my friend’s pre-conceived notion of how long a script had to be made her downplay it to her boss.

Of course, reading the script years later resulted in the maximum amount of second-hand embarrassment a person is allowed to endure. Soooo much could’ve been cut from that script. But because I wanted to include what *I* wanted to include in the story and because everything *I* wrote had to be genius, there’d been zero editing. The script, I realized, was all about me. As were all the scripts I’d written up to that point.

Around this time I started to read a lot of professional screenplays and noticed just how easy they were to read (The Hangover was a particular favorite). It hit me that I’d been doing it all wrong. I was writing for me, never once thinking about what the experience was for the reader. Ultimately, it’s about making them happy. So I completely changed the way I wrote. 135 page scripts became 110 page scripts. I began writing simpler easier-to-digest sentences (4th grade level instead of going to a thesaurus every tenth word). 4-5 line paragraphs became 2-3 line paragraphs. Crazy weird hard-to-follow artsy sequences were jettisoned entirely. Everything became geared towards giving the reader the most enjoyable experience possible. Yes, you have to be into what you’re writing. But ultimately you’re writing your script for others to enjoy, not yourself. So approach your scriptwriting accordingly.

Outlining is actually a good thing. Oh wait, outlining is actually a bad thing – Like most writers who get into screenwriting, I considered outlining the antithesis of creativity. If you planned what you were going to write ahead of time, you were purposefully stifling your moment-to-moment ability to seize upon inspiration. However, after writing a dozen or so screenplays without an outline, I began to notice I was spending an inordinate amount of time rewriting them. One day I decided that I needed to be more productive with my writing time and looked into what was causing me to rewrite so much. I realized that the bulk of my rewriting was focused on correcting my structure, which was all over the place. Why was it all over the place? Because I’d been taking my story whatever random direction I wanted to in the moment.

Outlining, I realized, corrected this problem. What you have to remember is that screenwriting is the most mathematical of the writing practices outside of maybe poetry. Every page is a minute of screen time. And most movies are between 100-120 minutes. So your length is already set. Therefore, it makes sense that you’d want to divide your script into the most dramatically powerful set of sequences to get the most out of it. Planning where everything goes isn’t anti-creative. It’s putting the pillars of your story in place so that it’s easy to build a story on top of them. There are about 45 scenes in a script. Your first act should have 25% of those scenes, the second act 50%, and the third act 25%. Figure out as much as you can about what goes on in each of those acts and your script is going to be more focused and more purposeful.

But wait! Years later, after following this strategy religiously, I realized it’d created a new problem. Now, my scripts were feeling too predictable. They were structured well and weren’t taking as long to write. But the story beats were all landing in the same spots that all story beats land, giving my scripts the distinctive feeling of “I’ve seen this movie already.” This was because, in my determination to become a structural superstar, I had eliminated all spontaneity. I’d forbidden the act of coming up with an idea on the spot and changing direction, since it went against my outline. Also, if I changed a major part of my outline, it would mean going back and changing the rest of the outline with it.

What I ultimately learned was that you need a balance of both. You need to outline ahead of time. But you also need to give yourself permission to go off on story tangents during the writing process, even if it means re-thinking your story. The act of writing a screenplay is a process of discovery. You will discover new things along the way. If those ideas are notably better than the ideas you had in your outline, by all means incorporate them.

Situation-based writing – In the past, I looked at screenplays as a series of scenes that are stacked together to tell a larger story. Not every one of these scenes needed to be individually entertaining as long as they worked with the other scenes to tell that story. Situation-based writing changed that. It made me realize that each scene could become a story all its own, so that not only was it a part of a larger whole, but was entertaining all by itself. And the concept is simple. Instead of just writing characters moving through your universe, bridges that connect the previous scene with the following one, create a SITUATION within the scene itself that makes it its own little mini-story.

Let me give you an example. Let’s say you want to write a work scene for your protagonist between him and his boss. Technically, you could write anything you wanted. You could have the boss remind your hero of an important presentation he has later. You could write a scene to establish that your hero kisses up to his boss whenever he can, in the hopes of getting a promotion at some point. You can write a scene with your hero and several co-workers talking to their boss after a meeting. None of these scenes would be bad, per se, if you wrote them competently. But none of them are situations. Situations have goals, stakes, and some sort of familiar container that audiences understand the rules of.

So, for example, your hero could have a meeting with his boss where he plans to ask him for a raise. That’s a situation. It’s an identifiable act with clear rules attached to it. Somebody wants something. We’d make sure to attach some stakes to it (it’s crucial that he get this raise). That’s going to be a way better scene than the other three scenes I mentioned specifically because of the compelling situation you’ve set up. In Coda, two high school kids who like each other do homework together in one of their bedroom’s for the first time. That’s a situation. It’s a non-situation if they just talk to each other after class. There’s no “container” to that scenario.

Speaking of high school, a teenager taking their driver’s test. That’s a situation. A road rage confrontation. That’s a situation. When Terry Rossio talks about this, the example he gives is, don’t have your married couple arguing back home, have them arguing on the side of the road while having to change a tire. The changing of the tire is the situation. Situations create a framework around the scene that makes it feel like a miniature movie. You’re not going to be able to do this in every scene. But try to do it in as many as possible.

The second act is the movie – At one point in my screenwriting journey, I was under the assumption that the first act was the movie. Because the first act was where you introduced your concept, which is the whole reason you wrote the movie. Take War of the Worlds, for example. The reason you get excited about writing that movie is what happens ten minutes into it, when these giant tripod aliens appear and start vaporizing everyone. But after writing a bunch of screenplays incorporating that approach, I realized that everything went to crap as soon as my first act was over. I’d introduced this really cool hook but I still had 90 pages to go. What was the point of those additional pages if the best stuff had already happened?

That’s when I internalized that scripts weren’t about introducing big fancy concepts then spinning your wheels for 60 pages until you got to the climax. What happens in the second act was actually the thing that connects with the audience the most. What I ultimately realized is that a screenplay is about a character who’s experiencing intense inner turmoil which is preventing them from finding happiness. The second act is about challenging that conflict to the point where they need to face it head on.

Take Everything Everywhere All at Once. The second act is about this unhappy woman who’s given up on both her life and her family being forced to cooperate with them in order to defeat a bigger evil. Sure, the opening act where we learn she can recruit powers from other universes is cool. But the meat of the story is her trying to connect with her other family members, and that’s 100% explored in the second act. Obviously, you’re throwing plot obstacles at your characters in the second act as well. But it’s primarily about your character being challenged internally. This was a major MAJOR revelation for me because it finally got me to understand what to do in my second act. Before that, I just tried to come up with enough non-boring scenes to get to the 3rd act.

Scripts are not about dialogue – When I started writing, I was heavily influenced, like a lot of people, by Tarantino. And what was Tarantino known for? His dialogue. So all of my early scripts were characters chatting, and chatting, and chatting some more. I think it was John August who said that once a scene was set up properly, anyone could write the dialogue. I don’t know if I completely agree with that. But I agree with the sentiment. What studios pay the big screenwriters for is creating the scenarios that lead to good dialogue as opposed to just writing a bunch of dialogue in a vacuum.

The most famous example of this is what happened on Thor Ragnarok when a Make-a-Wish foundation kid was on set and they were having issues with the line when Thor and Hulk meet each other in the gladiator ring. The kid suggested going with, “We know each other. He’s a friend from work.” The line became the most famous in the movie and some people in the screenwriting community, including myself, were asking that if screenwriting was so hard, how it is that a 10 year old kid can come up with the best line in a billion dollar movie? What we have to remember is that it’s the screenwriter who came up with the fun compelling situation of Thor being forced to fight Hulk in a surprise situation in a gladiatorial ring in the first place. Without them setting up that scene, there isn’t an opportunity for that fun line to exist.

In summary, focus more on creating situations that open the door for good dialogue rather than trying to create good dialogue out of thin air. Even the most famous dialogue scene in history, Jules and Vincent talking about foot rubs while going to collect money, is dialogue that doesn’t work as well if they’re just sitting on a couch rambling. The fact that they’re on their way to strong-arm a client for money builds a sense of inertia (they’re on the move) and anticipation (where are they going, what’s going to happen) that opens the door for a seemingly relaxed conversation.

This weekend, I’m offering $100 off a feature or pilot screenplay consultation. If you’ve got a script that has issues or a script you think is good but needs professional feedback to make it great, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “100” and collect on the deal. You have to secure payment this weekend but you can send the script whenever you want!