Genre: TV Pilot – Sci-fi/Thriller/Drama

Premise: In the near future, a robot is accused of murder for the first time ever. A young defense attorney must find out how to defend him, despite there being no precedent for the case.

About: Tin Man was written by Ehren Kruger, one of the biggest screenwriting names in town, as he’s written almost all of the Transformers movies. He also penned horror favorite, The Ring, and busted onto the scene with the awesome thriller, Arlington Road. While the draft I read of Tin Man is listed as a traditional pilot, I’m seeing on IMDB that Tin Man will be more of a TV movie. Not sure what that means, but this seems to be part of a new protective network trend designed to take risks without admitting failure. If the show doesn’t do well, they just say it was a one-off. If it does do well, they turn it into a series. Tin Man will air on NBC this year.

Writer: Ehren Kruger

Details: 54 pages – undated

Up-and-coming actor Patrick Heusinger will play the Tin Man!

Up-and-coming actor Patrick Heusinger will play the Tin Man!

Man, I had to work a long time and weed through a TON of pilots to find one that wasn’t a procedural. I saw everything from a detective who’s going blind and uses his other senses to solve crimes, to a lawyer who’s secretly an alien. Procedurals are the reason I’ve been uninterested in TV for so long. I never understood why you’d watch a show whose story didn’t evolve in subsequent episodes.

It wasn’t until serialized shows started making a big push after Lost that TV became interesting. But Hollywood loves its procedural television and doesn’t want to move away from it anytime soon. There seems to be two reasons for that. One, procedural television is a lot easier to write for on a long-term basis. Just give a lawyer a case to argue, a doctor a patient to save, or a detective a murder to solve, and you can write episode after episode after episode. The engine (goal) that drives each episode is built right into the format!

Two, it’s much easier for procedural shows to pick up new viewers. Understanding the show doesn’t require you to know what happened five episodes ago, whereas in a serialized show, like Breaking Bad, that’s not the case. We need to know that Walter killed that crazy ass drug dealer to understand why these two drug kingpins are after him this week.

This is, of course, changing. If you start hearing about a good serialized show, you can always “binge watch” it on Netflix and catch up to the series in the process. And you have to remember, we didn’t used to have huge DVD sets of an entire series, or the entire show a click away on Amazon or Itunes. So even when a show is over, it can still make a lot of money from old viewers as well as new ones. In other words, these days, TV is more receptive to the serialized format than ever.

Which is a good thing. Because the sooner we can get away from networks putting procedurals about cops in wheelchairs on television (Remember Ironside???) the better.

With that said, this still doesn’t solve that other issue: how to WRITE these serialized shows. When you write a serialized show, you have to come up with a new story engine EVERY SINGLE EPISODE. Think about how hard that is. With Grey’s Anatomy, all they had to do was say, “We just got a man in the East Wing who’s showing signs of pregnancy,” and that episode is taken care of. Coming up with original plot lines time and time again for shows like Lost and Breaking Bad is a lot more challenging than it looks.

Anyway, that’s a rather long rant that doesn’t have a whole lot to do with today’s pilot, so why don’t we switch gears and get to that.

Tim Man takes place in the near future and follows a robot named Adam Sentry (who looks 30 years old in human years). Adam is the creation of trillionaire (yes, with a “t”) Charles Vale, who owns a huge robotics company. Adam is Vale’s de facto robot Butler, and takes care of every aspect of his life, which is relevant, because Vale is sick and going to die soon.

Turns out it isn’t the cancer that gets him though. Vale is murdered in his home one evening. And who’s the only one in the house with him at the time? That’s right. Adam. So Adam is taken to the police station and read his Miranda Rights. Which sounded like a good idea at the time until the police realize that they can’t read Miranda Rights to a bunch of bolts and wires. That would imply he’s human.

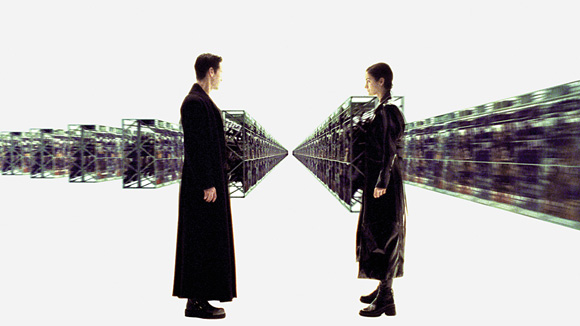

And thus the United States Court System must figure out how to proceed with the first ever robot accused of murder. Do they try him? Do they turn him into scrap metal? There’s all sorts of implications here, since if you try a robot, that implies robots are equal to humans, and then you start giving them rights, and pretty soon they’re running the world and then you have Terminators and then you have the Matrix.

Adam surprisingly asks for a dying breed to defend him, a HUMAN defense lawyer. Katie Piper sees this as an opportunity to bust out of being a glorified secretary and takes the job. But she learns the hard way that the Vale corporation doesn’t want Adam anywhere near a trial. They want him terminated. So when (spoiler) they try to kill him, Adam has no other choice but to resist everything that was programmed into him, and go on the run. He knows that his one shot at not being shut down, is finding out who killed Charles Vale, and why.

All you can really ask for from a show/script/movie is that the writer execute the idea in a way that isn’t obvious. I mean, you still want them to fulfill the promise of the premise. People who bought tickets for The Terminator because they heard it was about a killer cyborg want to see scenes where a cyborg kills people. But on the whole, if an idea is executed exactly as expected, it’s boring.

I don’t know about you, but I want to be surprised. I want the writer to be ahead of me. And Tin Man unravels slightly differently than I expected, which was refreshing. I think I was expecting a straight-forward boring delivery about the increasingly frequent debate (in sci-fi screenwriting) of whether robots should be given equal status to humans.

We get a little of that, but we also get this plucky human defense lawyer, a “dying breed,” who’s using this opportunity less as a noble cause and more as a way to advance her career. When that happened and I realized I wasn’t going to be preached to, I was on board.

And I liked the implication that Adam was holding a bunch of proprietary information, since he was Charles Vale’s personal robot, and what that could mean for the company if he went to trial and was forced to divulge those secrets. And therefore them wanting to kill him before he made it to trial. All of a sudden, there were a few more layers to the story than I expected. The stakes were higher than just “should we try robots?”

And the pilot didn’t end how I expected it to either. I assumed this was the beginning of a drawn out court case that would last half the first season. But at the end (spoiler), Adam escapes and we’re essentially introduced to a future version of The Fugitive. I was surprised at how closely this mimicked that premise, but it’s a recipe that definitely works, and thank god it keeps us away from procedural territory.

I don’t know if I had any problems with the script other than, maybe, it doesn’t feel ground-breaking enough? It feels a little too familiar? Robots seem to be the new craze in TV. We have Almost Human. Extant, coming up on CBS, and I’m sure at least a couple of series on SyFy.

This idea of people mimicking robots… I don’t know how else to put it but it feels like an easy way to squeeze a high concept into a small budget. Which is fine. Budget-wise, it’s a smart move. But I feel that audiences are becoming hip to this approach, which is why shows like Almost Human reek of cheapness. Occasionally showing the metal skeleton other underneath the skin after the robot gets cut—we’re kind of tired of that, seeing as we saw it all the way back in The Terminator.

I suppose it’s all in how its shot, the vision and what the production value is, but I need more than just “robots in human skin” these days to get excited about a series.

With that said, I think Kruger is a good writer. You may not agree when you see those Transformers credits, but the impression I get there is that he’s writing with 50 heads over his shoulder. In this case, with Tin Man, I see something solid. It’s not spectacular, but it’s a good pilot.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You don’t HAVE to write a strict “serialized” show or a strict “procedural” show. You can heavily serialize something (like Lost) or you can write a procedural with serialized elements, like The X-Files. The X-Files had plenty of standalone procedural shows, but then would have shows that solely dealt with the mythology. So don’t feel like you have to go only one way or only the other when making the procedural/serial choice.

So the Oscars are over and, as expected, it was nobody’s night. Awards were distributed evenly, which confuses news organizations and reporters because they love to splash across their headlines “IT WAS MOVIE X’S NIGHT!” Gravity won some. 12 Years won some. But nobody dominated. Were there surprises? You bet. American Hustle didn’t win a single award! And Barbrie Fontuno lost for Best Documentary Animated Short for the third year in a row. When is that guy going to finally get his statue!?

Which reminds me… Poor Leo continues to sit in the loser’s chair, despite playing more Oscar-friendly roles than any other actor in town and working with the best directors in the business. I don’t know what it is about Leo. He’s a good actor, but I don’t know if he’s a great one. He commands the screen. But there’s something in the back of his delivery that makes you aware that he’s acting. If he can figure out how to overcome that, the little golden statue may yet be his one day.

I was shocked that after Cate Blanchett won for Best Actress (which I think she deserved) she thanked every single person on the planet EXCEPT for Woody Allen. I don’t know if that’s because she doesn’t like Woody Allen or she’s afraid to give credit to a media-appointed child molester and deal with the backlash. But by omitting his name from the acceptance speech, she’s probably going to draw more attention about the director than had she just said his name.

In the director category, there is really no question that Alfonso Cuaron deserved to win. I’ve loved his stuff ever since that Ethan Hawke one-take running shot in Great Expectations, and then those amazing super-takes he did in Children of Men. But with Gravity, he topped them all. I mean, if you’re freaking inventing shit to make your movie, you get the Oscar. This guy invented the technology to make this film. That’s pretty awesome.

Matthew McConaughey for the Best Actor win. This was one of the only shoe-ins of the night. If there’s one thing that’s clear about this win, it’s that if you’re a good looking actor who loses 50+ pounds to look really skinny in your role, you increase your Oscar chances by 80%. This is a KNOWN FACT, and seemed to work for co-star Jared Leto as well. I think Matt had one of the funnier speeches of the night. With his confidence and that southern drawl, you’re captivated and believe everything the guy’s saying. But if you really listened to Matt, you may have noticed he was just babbling a bunch of nonsense. Somebody you look forward to? Somebody to be on top of? Somebody to call your hero? What??? I think at the end, Matt told the world that his hero was himself. Which is pretty much Hollywood acting in a nutshell.

So what do I think of 12 Years A Slave winning best picture? Well first of all, I haven’t seen the film. Let’s start there. Why haven’t I seen it? Two reasons. First, I think Steve McQueen is a self-indulgent filmmaker who doesn’t care about story. He just wants to get in there, shoot, and play around with the actors. “Shame” is one of the most unneeded stories ever to be written. It was a complete waste of everybody’s time except maybe Michael Fassbender. After that debacle, I decided I was never again going to watch a Steve McQueen movie.

Second, from everything I’ve been told about the film, it’s as if it was created specifically so that I would hate it. It’s over the top. It’s depressing. It’s more history lesson than film. I don’t have anything bad to say about the people who like it. But I go to the movies to be entertained, at least on some level. And this film has no interest in entertaining. Yeah, I get it. Sometimes movies are meant to challenge you. But it seems like the message of this film is one I already know. Slavery was really really really bad. I mean, if you guys can convince me that there’s another reason to see this that I’m not considering, let me know. But I just don’t see myself excitedly sitting down to watch 12 Years A Slave with a bucket of popcorn any time soon.

Which brings us to the only thing that matters about the Oscars – the screenwriting categories! Now in my newsletter, despite not feeling like there were any true contenders, screenplays that we would look back at in 10 years and go, “Oh yeah, that was an amazing screenplay,” I thought I could pick the winners. In the Adaptation side, we had…

Before Midnight

12 Years A Slave

Captain Phillips

Wolf of Wall Street

Philomena

I knew Captain Phillips had no shot. It’s basically a bunch of shaky cam with a Somali pirate occasionally saying, “Look at me! I’m the Cap-tun now.” Wolf of Wall Street was a copy and paste job from the book. And Philomena was way too small of an idea. That left 12 Years A Slave and Before Midnight. Since I had not seen 12 Years A Slave, I was making an educated guess. But from what I’ve been told, 12 Years A Slave was all about the acting and the directing. Of those three elements, the screenwriting was supposedly the least impressive of the group. On the flip side, Richard Linklater is known for being a kick-ass screenwriter, with the industry adoring the fact that Julie Delpy pitches in and helps write these “Before” movies. So I thought the Oscar would go to Before Midnight. But alas, 12 Years a Slave won.

But! The story is not over. For those of you conspiracy theorists, you may have heard a few days ago that Julie Delpy RAILED on the Academy, calling them a bunch of old white men who hadn’t done anything in forever, and who therefore needed money. So to win an Academy award, all you had to do was slip them some “presents” and you had their vote. She then went on to say that she could give two shits about Hollywood and the Academy and that she thinks almost everything that Hollywood makes sucks.

Wowzers! This is why I’ve always kept Mrs. Delpy an arm’s length away. You can see that, sort of, contained rage behind her eyes. You get the feeling that she just hates everyone and doesn’t appreciate what she has or the chances she’s been given. I think that’s why she was never really accepted into the Hollywood community. But either way, even though that only happened a few days ago, after the voting was in, I would not put it beyond the Academy to change some votes around to avoid this vitriolic woman coming up on stage and calling all of its members elitist criminals. So she may have done herself in and prevented herself from the opportunity to make a few more personal indie movies.

That leaves us with the Original Screenplay Nominees…

American Hustle

Her

Blue Jasmine

Nebraska

Dallas Buyers Club

I thought this race was between American Hustle and Blue Jasmine, both of which, I believe, were better screenplays than Her. American Hustle had a weird story and took chances, mixing humor with drama in a way that was unpredictable and entertaining. It was not only different (which is easy to do), but it executed its “different” approach almost flawlessly (which isn’t easy to do). Blue Jasmine was masterful in its character creation (this woman who was going nuts), in its situational setups (the repeatedly tough moments it placed its hero in), and then in its dialogue, which, with Woody Allen, is never stilted, always feels natural, and has that heightened lyrical quality to it, almost like you’re listening to two characters take part in an aural dance.

But upon reflection, I understand why Her won. It took the biggest chance of all. It created a romantic comedy without one of the key components of the genre – the girl! I mean, sure, there’s a girl, but we only hear her voice. To pull that off for an entire movie and keep us interested is a magic act. I just didn’t think Spike NAILED it, which is why I didn’t think it would win. But in a year of weak contenders, I guess a lot of people thought it was unique, and that was enough to elevate it against some flat competition.

Oh, and finally, I thought Ellen was great. She’s an awesome host. I want to eat pizza with Ellen and take selfies with her. How bout you? How was your Oscar evening? Did your picks pan out?

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

TITLE: GRIPPER

GENRE: Horror

LOGLINE: When a young geneticist attempts to save the world’s forests from a rabid insect infestation she unwittingly unleashes a plague of apocalyptic proportions.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: A new, original monster for the horror/nature gone wild sub-genre based on real science and current environmental concerns – and its a pretty swift read at 103 pgs. Plus, the first and last lines of dialogue are ‘fuck’ and ‘beautiful’ ;)

TITLE: Gone

GENRE: Supernatural Drama

LOGLINE: A woman’s past affair with a married writer haunts her in unusual ways.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’m a huge fan of the 1986 French film “Betty Blue”. Even though it’s really quite terrible. I remember reading about some arthouse theater in Houston doing a retrospective screening back in the mid-90’s. Perhaps it was being a teen with hormones running amock, along with a burgeoning interest in all things cinema — especially movies I could never see growing up in Crockett, Texas — but those notorious opening 5 minutes of “Betty” had me intrigued. So, while not a great piece of work by any means (it’s a rambling mess, especially the longer three-hour version, with a goofball denouement and incredibly stilted dialogue throughout)… still holds a special place with me.

I think I like the idea of the thing more than the thing. Thus, wanted to pull central story elements and play around with them. Pay homage.

Also, I wasn’t aiming for a surprise at the end, but I’m kinda tickled it’s there.

TITLE: The Cloud Factory

GENRE: WW2 romantic drama

LOGLINE: Torn between family and college or the love of an aristocratic lesbian doctor, a badly-injured American pilot grapples with her burgeoning sexuality and WW2 Britain’s rigid social order.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: ‘The Cloud Factory’, is based on the true story of the women’s section of Britain’s Air Transport Auxiliary, with fictional protagonists. Now, I get that Hollywood seems to think period romances and period dramas are so boorrring. Let’s take ‘Philomena’ (part period drama, and part contemporary). Probably made for less than $10 million; its global box office gross to the end of January was $68 million. Making money’s so boorrring. ‘Atonement’ – made for some $30m with global box office of $120m+. Boring! ‘The English Patient’ – production budget in the high $20m region; global gross of around a quarter of a billion dollars. Really boring! They all had strong female leads involved in a romantic relationship that didn’t end well, in common. Women over 30 especially turn out in droves for relationship dramas with strong female leads because we get to see so darned few good ones. See Lindsay Doran’s TED talk on relationships in movies – women get it! It’s not rocket science. So that is what I’ve written. I’ve just given the period romantic drama a little twist to keep things interesting. And I could be wrong, but as far as I can see, the last time a period drama seems to have gotten a run on Amateur Offerings Week was ‘Templar’ back in August, 2013. Long overdue, surely.

TITLE: The Triennial

GENRE: Action/Thriller

LOGLINE: An elite Israeli secret agent is on loan to the US teams with an unlikely civilian in a race to infiltrate and eliminate a terrorist cell in Chicago.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: During the last couple years, I’ve had three comedy scripts show up nicely in the contest circuit, yet none gained any traction with agents, managers, or producers. Apparently, I crack myself up. So I changed lanes and wrote this action/thriller feature, because… it’s a business, right? Bottom line – I had a blast writing this one, so I’m really glad I left my comfort zone and tried a new genre. Only question – will anyone else be glad? Would love some scared straight feedback.

TITLE: Fantasy Man

GENRE: Comedy

LOGLINE: A fantasy footballer must convince a sports star to play, or else a mob boss will have him killed.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: The story. Period. Even if you’re not into fantasy football, there’s a heartfelt story here about friendship, love and going after your dreams. And it’s also pretty fucking funny. Happy reading and we appreciate everyone’s comments in advance. Thank you.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Horror/Contained/Thriller

Premise (from writer): When a bed-ridden teen discovers his online crush has been murdered, he investigates her death, leading him on a hunt to stop her killer before he strikes again.

Why You Should Read: Gary’s script received many up-votes in the comments section!

Writer: Gary Rowlands

Details: 97 pages

Rising star Logan Lerman for David?

Rising star Logan Lerman for David?

Gary had it out for me in yesterday’s comments. But I understand his frustration. I hadn’t sent out a newsletter in a few weeks, and I know it sucks not knowing when those things are coming, especially when they sometimes end up in the SPAM box (I believe this has something to do with providing links in each newsletter). But none of that matters anymore because the newsletter went out last night and boy was it a doozy. You’ll definitely want to fish for it as it’s well worth your time. And if you’re not on the newsletter list, then by golly you should be. Sign up here.

So why did today’s script get picked? Well, Gary informed me that his script had gotten over 30 up-votes in the Disqus comments. I’m not sure exactly what that means (does that mean these people read the whole thing? Part of it? That they just liked Gary?) but we didn’t have an Amateur Offerings post last week, so I needed a script to review. Call it opportunity colliding with luck. And hey, the horror market’s hot right now with a big horror spec sale yesterday (about that suspicious death on the top of that Los Angeles hotel), so maybe Gary can keep the streak going.

When we meet 17 year-old David Fletcher, he’s sprinting through the forest in the middle of the night. We’re not sure why, but we’re guessing there’s something behind him that he wants to get away from. That’s usually how midnight runs work. David makes it to a highway, and seemingly to safety, except highways are where those pesky automobiles dart around, and no sooner than David remembers that than one slams into him. This results in a powerful near death experience, where David sees the whole tunnel and bright light and everything.

Cut to David in his bedroom a few weeks later. He’s in bad shape, bad enough where he can’t even leave his bed. And we all know what that means. The perfect excuse to ALWAYS BE ON THE INTERNET! David surfs the internet constantly, and one night, late, runs into a mysterious hot little number named Debbie, who he starts webcamming with.

Debbie seems cool, until we realize she’s DEAD. Yes, David realizes he saw Debbie in the tunnel. And he can’t tell her because she’s terrified of dying. Meanwhile, a local female cop comes around asking questions about Debbie, since the person who killed her is a serial killer and will strike again once the next full moon strikes. There’s something suspicious about this officer so David keeps his info close to the vest.

Once David comes to terms with the reality that he’s web-camming with a ghost, he decides to call a psychic, a Chinese woman named Mei Li. Mei Li tells David he MUST find out who Debbie’s boyfriend was as she thinks that’s the guy killing all these girls during all these full moons. The problem is, Debbie’s a human lie detector and knows when David’s trying to juke her, which leaves David with no juking options.

Eventually, the killer kills again and it all comes to a head, with everybody a suspect. The cop, the mysterious driver who almost killed David, and David himself! And if that isn’t bad enough, David’s also gotta inform Debbie that she’s not a real person anymore. She’s a ghost. Talk about an odd way to start a relationship!

I gotta give it to Gary. Offline was super easy to read. Like most scripts that end up on Amateur Friday, the mechanics were very strong. The opening was a bit too poetic for my taste (be careful about being too lyrical. You risk sacrificing clarity for prose), but after that, the prose was simple and to the point.

After that first scene though, the script started to run into some problems in my eyes. It started with little things. Like David going through his photo album, which conveniently contained newspaper articles about him being arrested at 14 and his dad’s suicide. Why would you keep articles of these things in an otherwise happy photo album other than you’re trying to cheaply convey exposition?

Also, many of the characters and moments in Offline were either heavy-handed, cliché, or both. For example, voices in the room chant “Omnibus” which David looks up. Turns out it translates directly to “Death to all.” The keys on his computer randomly type on their own. What do they spell? “D-e-m-o-n.” The serial killer only ever kills on one day. When? During a full moon. David is asked what his favorite memory is. Going to a ball game with his dad. There were too many of these moments where it didn’t feel like Gary dug deep enough. He just went with the first thing that popped into his head, and that always amounts to an overall cliché story.

Once we hit the stereotypical inadvertently funny Asian psychic, that’s when I officially knew this story wasn’t going to work for me. Mei Li giving David advice in her funny Chinese accent just made this script too goofy. This led to other somewhat goofy choices, like how the killer only killed women who wore Jimmy Choo shoes (and would keep one shoe as a memento).

The dialogue also needed work. Much of it was very straight-forward and on-the-nose, like on page 47, where David talks about his dad committing suicide and not even leaving him a note: “Nothing matters. Not now. Not then. Least not me. Not to Dad. Fact he had a son who idolized him never made a difference. It didn’t matter… I DIDN’T MATTER.” Debbie gazes at him. Wants to say something. Hesitates. “You matter to me.”

I understand that sometimes you want you characters to say what they feel, but not this early, and this is way too on-the-nose. People just don’t talk this way in real life. Or later, on page 68:

[David] “kisses the tip of his index finger, gently presses it against Debbie’s soft lips via the screen.” Debbie: (smiles) “What was that for?” David: “Believing in me.” I know these moments feel “right” when you’re writing them because there’s so much emotion being conveyed. But when you’re looking at this exchange from the other side, you’re saying, “Oh man, that was so on-the-nose and over-the-top!” It can take a writer awhile to finally see that these moments aren’t achieving what he believes they are. Readers do not respond well to on-the-nose emotion.

And we haven’t even gotten to the most controversial aspect of this script, which is that it takes place in one room (except for the beginning). On the one hand, this is great. It means a really cheap movie that the writer can make himself! On the other, it’s bad, because it means lack of variety, considerably upping the probability that the reader (and audience) will get bored.

Gary does a pretty good job keeping the plot moving though, even with this handicap. There are lots of a little twists and turns along the way. And we do have our GSU firmly in place (David’s got to find the killer before he strikes again, which is very soon, with the upcoming full moon). He also has an intriguing character in the stepmom, who has schizophrenia and constantly abuses David. It was a bit too much like Misery at times, but different enough to feel like its own thing.

So that was good. But the overall problem remains: the story is too on-the-nose and too many cliché choices were made. If a malevolent entity is trying to scare someone, I don’t think they’re going to ghost-type “Demon” on the keys. They’re going to type something much more random and confusing, something so strange that it will scare the crap out of us.

In this next draft and moving forward, I’d love to see Gary challenge himself more and try and eliminate all his cliché choices. Take chances. Don’t give us what we’ve already seen before. Try to carve your own path whenever you write. That’s how your voice comes out. I wish him luck!

Script link: Offline

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Over-emotion on the page usually creates the opposite effect on the reader.

Inception’s first act is pretty awesome.

Inception’s first act is pretty awesome.

It surprises me that people have trouble with the first act because it’s easily the most self-explanatory act there is. Introduce your hero, then your concept, then send your hero out on his/her journey. But I suppose I’m speaking as someone who’s dissected a lot of first acts. And actually, when I really start thinking about it, it does get tricky in places. The most challenging part is probably packing a ton of information into such a small space. So that’s something I’ll be addressing. Also, I’ve decided to include my second and third act articles afterwards so that this can act as a template for your entire script. Hopefully, this gives you something to focus on the next time you bust open Final Draft. Let’s begin!

INTRODUCE YOUR HERO (page 1)

Preferably, the first scene will introduce your hero. This is a very important scene because beyond just introducing your hero, you’re introducing yourself as a writer. A reader will be making quick judgments about you on everything from if you know how to write, if you know how to craft a scene, and what level you’re at as a screenwriter. So of all the scenes in your script, this is the one that you’ll probably want to spend the most time on. It’s also extremely important to DEFINE your hero with this scene. Whatever the biggest strength and/or weakness of your hero, try to construct a scene that shows us that. Finally, try to convey who your hero is THROUGH THEIR ACTIONS (as opposed to telling us). If your hero is afraid to take initiative, give them the option in the scene to take initiative, then show them failing to do so. A great opening scene that shows all of these things is the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

SET UP YOUR HERO’S WORLD (pages 3- 15)

The next few scenes will consist of showing us your hero’s world. This might show him/her at work, with friends, with family, going about their daily life. This is also the section where you set up most of the key characters in the script. In addition to setting up their world, you want to hit on the fact that something’s missing in their life, something the hero might not even be aware of. Maybe they’re missing a companion (Lars and the Real Girl). Maybe they’re putting work over family (George Clooney in Up in the Air). Maybe they’re allowing others to push them around (American Beauty). It’s important NOT TO REPEAT scenes in this section. Keep it between 2-5 scenes because between pages 12-15, you’re going to want to introduce the inciting incident.

INCITING INCIDENT (pages 12-15)

Introducing the inciting incident is just a fancy way of saying, “Introducing a problem that rocks your protagonist’s world.” This problem makes its way into your hero’s life, forcing them to act. Maybe their plane crashes (The Grey), they get someone pregnant (Knocked Up), or their daughter gets kidnapped (Taken). Now your hero is forced to make a decision. Do they act or not? — It should be noted that sometimes the inciting incident will arrive immediately, as in, on the very first page. For example, if a character wakes up with amnesia (Saw, The Bourne Identity) or something traumatic happens in the opening scene (Garden State – his father dies), the hero is encountering their inciting incident (their problem) immediately.

HELL NO, I AIN’T GOIN (aka “Refusal of the Call”) (roughly pages 16-25)

The “Hell No I ain’t goin” section occurs right after the inciting incident and basically amounts to your character saying (you guessed it), “I’m not goin anywhere.” The reason you see this in a lot of scripts is because it’s a very human response. Humans HATE change. They hate facing their fears. The problem that arises from the inciting incident is usually a manifestation of their deepest fear. So of course they’re going to reject it. Neo says no to scaling a building for Morpheus and gives in to the baddies instead. This sequence can last one or several scenes. It’ll show your hero trying to go back to what they know.

OFF TO THE JOURNEY (page 25)

When your character decides to go off on their journey (and hence into the second act), it’s usually because they realize this problem isn’t going away unless they deal with it. So in order to erase this eternal snowfall, Anna from Frozen must go off, find her sister and ask her to end it. This is where the big “G” in “GSU” comes from. As your hero steps into that second act, it begins the pursuit of their goal, which is to solve the problem.

GRAB US IMMEDIATELY

Now that you know the basic structure, there’s a few other things you want to focus on in the first act. The first of those things? Don’t fuck around! Readers are impatient as hell, expecting you to be bad writer (since you’re an amateur) and judging you immediately. So try and lure them in with a kick-ass scene right away and don’t let them off the hook (each successive scene should be equally as page-turning). This doesn’t mean start with an action scene (although you can). It could mean a clever reversal scene or an unexpected twist in the middle of the scene. Pose a mystery. A murder. Show us something that’s impossible (people jumping across roofs – The Matrix). Use your head and just make us want to keep turning the pages even if our fire alarm is going off in the other room. Achieving this tall order WHILE doing all the other shit I listed above (set up your hero and his flaw), is what makes writing so tricky.

MAKE IT MOVE

It’s important that the first act move. Bad writers like to DRILL things into the reader’s head over and over and over again. For example, if they want to show how lonely their hero is, they’ll show like FIVE SCENES of them being lonely. And guess what us readers are doing? We’re already skimming. Typically, a reader picks things up quickly if you display/convey information properly. Show that your hero is bad with women in the first scene, we’ll know they’re bad with women. There are some things you want to repeat in a script (a character’s flaw, for example) but you want to slip that into scenes that are entertaining and necessary for the story, not carve out entire scenes that are ONLY reiterating something we already know. This is one of the BIGGEST tells for an amateur writer, so avoid it at all costs!

ENTERTAIN US WHILE SETTING US UP

You’re setting up a lot of stuff in your first act. You’re setting up your main character’s everyday life, their flaws, the love interest (possibly), secondary characters, the inciting incident, setups for later payoffs. For that reason, a first act can quickly turn into an information dump. That’s fine for a first draft. But as you rewrite, you’ll want to smooth all this information over, hide it even, and focus on ENTERTAINING US. Nobody’s going to pat you on your back for doing everything I’ve listed above. That stuff is EXPECTED. They’re only going to pat you on the back if your first act is entertaining. Think of it like this. Nobody wants to know how a roller coaster works. They just want to ride on it.

EVERY SCRIPT IS UNIQUE

One of the hardest things about writing is that every story presents unique challenges that force you to improvise. Nobody’s going to be able to follow the formula I laid out to a “T.” You’re going to have to adjust, improvise, invent. That shouldn’t be scary. You’re artists. That’s what you do. Just to give you a few examples, Luke Skywalker is not introduced in the beginning of Star Wars. Marty McFly doesn’t choose to go on his adventure. He’s thrust into it unexpectedly (when his car jumps back to the past). Some films, like Crash, have multiple characters that need to be set up. This requires you to set up a dozen little mini-stories (for each character) as opposed to one big one. Some scripts start with a teaser (Jurassic Park) or a preamble (Inception). The point is, don’t pigeonhole yourself into the above unless you have a very straightforward plot (like Taken, Rocky, or Gravity). Otherwise, be adaptable. Understand where your story is resisting structure, and be open to trying something different.

IN SUMMARY

That’s probably the scariest thing about writing, is tackling the unknown. So what do you do if you come upon these unique challenges? What do you do with your first act, for example, if the inciting incident happens right away, as it does in The Bourne Identity? Do you still break into the second act on page 25? Well, I know the answer to that question as well as some other tricky scenarios, but they’d require their own article (short answer – you break into the second act a little earlier, around page 20). What I’ll say is, this is one of the big things that separates the pros from the amateurs. The pro, because he’s written a lot more, has encountered more problematic scenarios and had more experience trying to solve them. The only way to catch up to them is to keep writing a lot (not just one script, but many, since each script creates its own set of challenges) and figure out these answers for yourselves. The good news is, with this article, you have a template to start from. And remember, when all else fails, storytelling boils down to one simple coda: A hero encounters a problem and must find a solution. That’s true for a story. It’s true for individual characters. It’s true for subplots. It’s true for individual scenes. If you follow that layout, you should do fine. And if you want to get into more detail about this stuff, check out my book, which is embarrassingly cheap at just $4.99 on Amazon! ☺

THE SECOND ACT!

Character Development

One of the reasons the first act tends to be easy is because it’s clear what you have to set up. If your movie is about finding the Ark, then you set up who your main character is, what the Ark is, and why he wants to get it. The second act isn’t as clear. I mean sure, you know your hero has to go off in pursuit of his goal, but that can get boring if that’s the ONLY thing he’s doing. Enter character development, which really boils down to one thing: your hero having a flaw and having that flaw get in the way of him achieving his goal. This is actually one of the more enjoyable aspects of writing. Because whatever specific goal you’ve given your protag, you simply give them a flaw that makes achieving that goal really hard. In The Matrix, Neo’s goal is to find out if he’s “The One.” The problem is, he doesn’t believe in himself (his flaw). So there are numerous times throughout the script where that doubt is tested (jumping between buildings, fighting Morpheus, fighting Agent Smith in the subway). Sometimes your character will be victorious against their flaw, more often they’ll fail, but the choices they make and their actions in relation to this flaw are what begin to shape (or “develop”) that character in the reader’s eyes. You can develop your character in other ways (via backstory or everyday choices and actions), but developing them in relation to their flaw is usually the most compelling part for a reader to read.

Relationship Development

This one doesn’t get talked about as much but it’s just as important as character development. In fact, the two often go hand in hand. But it needs its own section because, really, when you get into the second act, it’s about your characters interacting with one another. You can cram all the plot you want into your second act and it won’t work unless we’re invested in your characters, and typically the only way we’re going to be invested in your characters is if there’s something unresolved between them that we want resolved. Take last year’s highest grossing film, The Hunger Games. Katniss has unresolved relationships with both Peeta (are they friends? Are they more?) and Gale (her guy back home – will she ever be able to be with him?). We keep reading/watching through that second act because we want to know what’s going to happen in those relationships. If, by contrast, a relationship has no unknowns, nothing to resolve, why would we care about it? This is why relationship development is so important. Each relationship is like an unresolved mini-story that we want to get to the end of.

Secondary Character Exploration

With your second act being so big, it allows you to spend a little extra time on characters besides your hero. Oftentimes, this is by necessity. A certain character may not even be introduced until the second act, so you have no choice but to explore them there. Take the current film that’s storming the box office right now, Frozen. In it, the love interest, Kristoff, isn’t introduced until Anna has gone off on her journey. Therefore, we need to spend some time getting to know the guy, which includes getting to know what his job is, along with who his friends and family are (the trolls). Much like you’ll explore your primary character’s flaw, you can explore your secondary characters’ flaws as well, just not as extensively, since you don’t want them to overshadow your main character.

Conflict

The second act is nicknamed the “Conflict Act” so this one’s especially important. Essentially, you’re looking to create conflict in as many scenarios as possible. If you’re writing a haunted house script and a character walks into a room, is there a strange noise coming from somewhere in that room that our character must look into? That’s conflict. If you’re writing a war film and your hero wants to go on a mission to save his buddy, but the general tells him he can’t spare any men and won’t help him, that’s conflict. If your hero is trying to win the Hunger Games, are there two-dozen people trying to stop her? That’s conflict. If your hero is trying to get her life back together (Blue Jasmine) does she have to shack up with a sister who she screwed over earlier in life? That’s conflict. Here’s the thing, one of the most boring types of scripts to read are those where everything is REALLY EASY for the protagonist. They just waltz through the second act barely encountering conflict. The second act should be the opposite of that. You should be packing in conflict every chance you get.

Obstacles

Obstacles are a specific form of conflict and one of your best friends in the second act because they’re an easy way to both infuse conflict, as well as change up the story a little. The thing with the second act is that you never want your reader/audience getting too comfortable. If we go along for too long and nothing unexpected happens, we get bored. So you use obstacles to throw off your characters AND your audience. It should also be noted that you can’t create obstacles if your protagonist ISN’T PURSUING A GOAL. How do you place something in the way of your protagonist if they’re not trying to achieve something? You should mix up obstacles. Some should be big, some should be small. The best obstacles throw your protagonists’ plans into disarray and have the audience going, “Oh shit! What are they going to do now???” Star Wars is famous for one of these obstacles. Our heroes’ goal is to get the Death Star plans to Alderaan. But when they get to the planet, it’s been blown up by the Death Star! Talk about an obstacle. NOW WHAT DO THEY DO??

Push-Pull

There should always be some push-pull in your second act. What I mean by that is your characters should be both MAKING THINGS HAPPEN (push) and HAVING THINGS HAPPEN TO THEM (pull). If you only go one way or the other, your story starts to feel predictable. Which is a recipe for boredom. Readers love it when they’re unsure about what’s going to happen, so you use push-pull to keep them off-balance. Take the example I just used above. Han, Luke and Obi-Wan have gotten to Alderaan only to find that the planet’s been blown up. Now at this point in the movie, there’s been a lot of push. Our characters have been actively trying to get these Death Star plans to Alderaan. To have yet another “push” (“Hey, let’s go to this nearby moon I know of and regroup”) would continue the “push” and feel monotnous. So instead, the screenplay pulls, in this case LITERALLY, as the Death Star pulls them in. Now, instead of making their own way (“pushing”), something is happening TO them (“pull”). Another way to look at it is, sometimes your characters should be acting on the story, and sometimes your story should be acting on the characters. Use the push-pull method to keep the reader off-balance.

Escalation Nation

The second act is where you escalate the story. This should be simple if you follow the Scriptshadow method of writing (GSU). Escalation simply means “upping the stakes.” And you should be doing that every 15 pages or so. We should be getting the feeling that your main character is getting into this situation SO DEEP that it’s becoming harder and harder to get out, and that more and more is on the line if he doesn’t figure things out. If you don’t escalate, your entire second act will feel flat. Let me give you an example. In Back to the Future, Marty gets stuck in the past. That’s a good place to put a character. We’re wondering how the hell he’s going to get out of this predicament and back to the present. But if that’s ALL he needs to do for 60 pages, we’re going to get bored. The escalation comes when he finds out that he’s accidentally made his mom fall in love with him instead of his dad. Therefore, it’s not only about getting back to the present, it’s about getting his parents to fall in love again so he’ll exist! That’s escalation. Preferably, you’ll escalate the plot throughout the 2nd act, anywhere from 2-4 times.

Twist n’ Surprise

Finally, you have to use your second act to surprise your reader. 60 pages is a long time for a reader not to be shocked, caught off guard, or surprised. I personally love an unexpected plot point or character reveal. To use Frozen, again, as an example, (spoiler) we find out around the midpoint that Hans (the prince that Anna falls in love with initially) is actually a bad guy. What you must always remember is that screenwriting is a dance of expectation. The reader is constantly believing the script is going to go this way (typically the way all the scripts he reads go). Your job is to keep a barometer on that and take the script another way. Twists and surprises are your primary weapons against expectation, so you’ll definitely want to use them in your second act.

IN SUMMARY

In summary, the second act is hard. But if you have a structural road-map for your story (you know where your characters are going and what they’re going after), then these tools should fill in the rest. Hope they were helpful and good luck implementing them in your latest script. May you be the next giant Hollywood spec sale! :)

THE THIRD ACT!

THE GOAL

Without question, your third act is going to be a billion times easier to write if your main character is pursuing a goal, preferably since the beginning of the film. “John McClane must save his wife from terrorists” makes for a much easier-to-write ending than “John McClane tries to figure out his life” because we, the writer, know exactly how to construct the finale. John McClane is either going to save his wife or he’s going to fail to save his wife. Either way, we have an ending. What’s the ending for “John McClane tries to figure out his life?” It’s hard to know because that scenario is so open-ended. The less clear your main character’s objective (goal) is in the story, the harder it will be to write a third act. Because how do you resolve something if it’s unclear what your hero is trying to resolve?

THE LOWEST POINT

To write a third act, you have to know where your main character is when he goes into the act. While this isn’t a hard and fast rule, typically, putting your hero at his lowest point at the end of act two is a great place to segue into the third act. In other words, it should appear at this point in the story that your main character has FAILED AT HIS/HER GOAL (Once Sandra Bullock gets to the Chinese module in GRAVITY, that’s it. Air is running out. She doesn’t understand the system. There are no other options). Either that, or something really devastating should shake your hero (i.e. his best friend and mentor dies – Obi-Wan in Star Wars). The point is, it should feel like things are really really down. When you do this, the audience responds with, “Oh no! But this can’t be. I don’t want our hero to give up. They have to keep trying. Keep trying, hero!” Which is exactly where you want them!

REGROUP

The beginning of the third act (anywhere from 1-4 scenes) becomes the “Regroup” phase. This phase often has to deal with your hero’s flaw, which is why it works so well in comedies or romantic comedies, where flaws are so dominant . If your hero is selfish, he might reflect on all the people he was selfish to, apologize, and move forward. But if this is an action film, it might simply mean talking through the terrible “lowest point” thing that just happened (Luke discussing the death of Obi-Wan with Han) and then getting back to it. Your hero was just at the lowest point in his/her life. Obviously, he needs a couple of scenes to regroup.

THE PLAN

Assuming we’re still talking about a hero with a goal, now that they’ve regrouped, they tend to have that “realization” where they’re going to give this goal one last shot. This, of course, necessitates a plan. We see this in romantic comedies all the time, where the main character plans some elaborate surprise for the girl, or figures out a way to crash the big party or big wedding. In action films, it’s a little more technical. The character has to come up with a plan to save the girl, or take down the villain, or both. In The Matrix, Neo needs to save Morpheus. He tells Trinity the plan, they go outfit themselves with guns from the Matrix White-Verse, and they go in there to get Morpheus.

THE CLIMAX SCENE

This should be the most important scene in your entire script. It’s where the hero takes on the bad guy or tries to get the girl back. You should try and make this scene big and original. Give us a take on it that we’ve never seen in movies before. Will that be hard? Of course. But if you’re rehashing your CLIMAX SCENE of all scenes?? The biggest and most important scene in the entire screenplay? You might as well give up screenwriting right now. If there is any scene you need to challenge yourself on, that you need to ask, “Is this the best I can possibly do for this scene?” and honestly answer yes? This is that scene!

THE LOWER THAN LOWEST POINT

During the climax scene, there should be one last moment where it looks like your hero has failed, that the villain has defeated him (or the girl says no to him). Let’s be real. What you’re really doing here is you’re fucking with your audience. You’re making them go, “Nooooooo! But I thought they were going to get together!” This is a GOOD THING. You want to fuck with your audience in the final act. Make them think their hero has failed. I mean, Neo actually DIES in the final battle in The Matrix. He dies! So yeah, you can go really low with this “true lowest point.” If the final battle or confrontational or “get-the-girl” moment is too easy for our hero, we’ll be bored. We want to see him have to work for it. That’s what makes it so rewarding when he finally succeeds!

FLAWS

Remember that in addition to all this external stuff that’s going on in the third act (getting the girl, killing the bad guy, stopping the asteroid from hitting earth), your protagonist should be dealing with something on an internal level as well. A character battling their biggest flaw on the biggest stage is usually what pulls audiences and readers in on an emotional level, so it’s highly advisable that you do this. Of course, this means establishing the flaw all the way back in Act 1. If you’ve done that, then try to tie the big external goal into your character’s internal flaw. So Neo’s flaw is that he doesn’t believe in himself. The only way he’ll be able to defeat the villain, then, is to achieve this belief. Sandra Bullock’s flaw in Gravity is that she doesn’t have the true will to live ever since her daughter died. She must find that will in the Chinese shuttle module if she’s going to survive. If you do this really well, you can have your main character overcome his flaw, but fail at his objective, and still leave the audience happy (Rocky).

PAYOFFS

Remember that the third act should be Payoff Haven. You should set up a half a dozen things ahead of time that should all get some payin’ off here in the finale. The best payoffs are wrapped into that final climactic scene. I mean who doesn’t sh*t their pants when Warden Norton (Shawshank spoiler) takes down that poster from the wall in Andy Dufresne’s cell? But really, the entire third act should be about payoffs, since almost by definition, your first two acts are setups.

OBSTACLES AND CONFLICT

A mistake a lot of beginner writers make is they make the third act too easy for their heroes. The third act should be LOADED with obstacles and conflict, things getting in the way of your hero achieving his/her goal. Maybe they get caught (Raiders), maybe they die (The Matrix), maybe the shuttle module sinks when it finally gets back to earth and your heroine is in danger of drowning (Gravity). The closer you get to the climax, the thicker you should lay on the obstacles, and then when the climactic scene comes, make it REALLY REALLY hard on them. Make them have to earn it!

NON-TRADITIONAL THIRD ACTS (CHARACTER PIECES)

So what happens if you don’t have that clear goal for your third act? Chances are, you’re writing a character piece. While this could probably benefit from an entire article of its own, basically, character pieces still have goals that must be met, they’re just either unknown to the hero or relationship-related. Character pieces are first and foremost about characters overcoming their flaws. So if your hero is selfish, your final act should be built around a high-stakes scenario where that flaw will be challenged. Also, character piece third acts are about resolving relationship issues. If two characters have a complicated past stemming from some problem they both haven’t been able to get over, the final act should have them face this issue once and for all. Often times, these two areas will overlap. In other words, maybe the issue these two characters have always had is that he’s always put his own needs over the needs of the family. The final climactic scene then, has him deciding whether to go off to some huge opportunity or stay here and takes care of the family. The scenario then resolves the character flaw and the relationship problem in one fell swoop! (note: Preferably, you are doing this in goal-oriented movies as well)

IN SUMMARY

While that’s certainly not everything, it’s most of what you need to know. But I admit, while all of this stuff is fun to talk about in a vacuum, it becomes a lot trickier when you’re trying to apply it to your own screenplay. That’s because, as I stated at the beginning, each script is unique. Indiana Jones is tied up for the big climax of Raiders. That’s such a weird third act choice. In Back To The Future, George McFly’s flaw is way more important than our hero, Marty McFly’s, flaw. When is the “lowest point before the third act” in Star Wars? Is it when they’re in the Trash Compactor about to be turned into Star Wars peanut butter? Or is at after they escape the Death Star? I think that’s debatable. John McClane never formulates a plan to take on Hanz in the climax. He just ends up there. The point is, when you get into your third act, you have to be flexible. Use the above as a guide, but don’t follow it exactly. A lot of times, what makes a third act memorable is its imperfections, because it’s its imperfections that make it unpredictable. If you have any third act tips of your own, please leave them in the comments section. Wouldn’t mind learning a few more things about this challenging act myself!