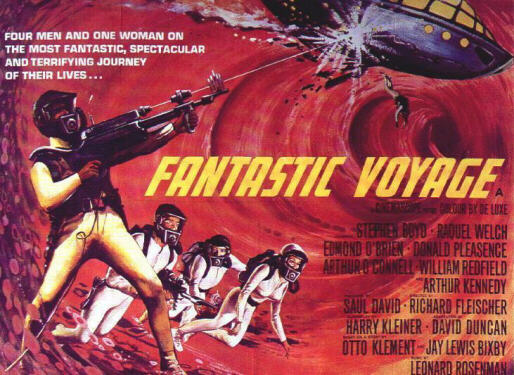

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: A submarine and its crew are shrunken down to microscopic size and injected into the bloodstream of a woman in order to save her.

About: The original Fantastic Voyage came out in the 60s, and since everything must be remade, they’ve been trying to get this project going for a couple decades now. The good news is they have the firepower that is James Cameron behind it (as producer), although he’s so wrapped up in his Avatar universe, I’m not sure how much time he’s able to give. Sean Levy (helmer of the underrated “Real Steel”) was listed as director as late as two years ago, but there hasn’t been a lot of news on the project since, so it’s unclear if he’s still involved. The draft I’m reviewing is an old one (from 2006) since it is from a couple of my favorite writers, Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver. I really wanted to see what they did with the idea.

Writers: Screenplay by Harry Kleiner – current revisions by Rick Jaffa & Amanda Silver

Details: April 28, 2006 draft

I am a huge fan of Amanda Silver and Rick Jaffa. Listening to their interview on Jeff Goldsmith’s podcast shows you just how dedicated they are and how well they understand this craft. Particularly hearing how they won over 20th Century Fox with their take on Rise of the Planet of the Apes, which I believe to be one of the biggest risks a studio has ever taken. They made a silent movie. A SILENT MOVIE, where the main character is an animal and doesn’t speak. It’s NUTS. Anyone who could make that work, I’m willing to trust them with anything.

I profess to not knowing much about Fantastic Voyage other than the snippets I run into online every once in awhile, but if the last film came out in 1966 and I’m still hearing about it, there’s gotta be a story worth mining there, right? That’s not to say I don’t have concerns. Shrinking people down and sending them inside a human body has a bit of a kitschy dated feel to it. I’m sure that’s what all the development meetings come down to. How do we make this current? It’s a task I’d be terrified of as a writer. Which is why I’m so interested in Silver and Jaffa’s take. These guys have proven they know how to think outside the box and take chances. Let’s see if they did that here.

Megan Colby works at something called The Alliance Research Facility. The year is 2185. And there’s a lot of unrest in the world. For that reasons, everyone’s been implanted with a microscopic chip that tracks their whereabouts and can be remotely detonated if you’re a bad boy. Or, in Megan’s case, a bad girl. Which Megan very much is at the time we meet her.

She illegally sneaks out of the facility and meets up with some rebels who jam a resistor something-or-other into her neck that prevents the Alliance from remotely detonating her chip. The problem is, the chip is programmed to automatically detonate within six hours of no contact. So she’s not out of the woods yet.

We eventually learn that Megan has actually injected a second chip into her body, the Alliance’s new prototype chip that is going to change the way…. Well, I guess change the way they can execute people. That’s why she escaped the facility, to get this chip to the rebels. But therein lies the problem. These chips are INSIDE of her. Which begs the question: how do they get them out??

Enter Dr. Charles Grant, a handsome professor who used to be in love with Megan until she abruptly left him. Grant is an expert in the human body, which is why he’s recruited by the rebels to join them in their mission – miniaturize themselves inside a submarine, go inside Megan’s body, and retrieve the two chips.

They only have six hours before the chips explode, so they have to act fast. Megan is being kept in a coma in the meantime, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to be easy. As Grant tells everyone, the human body has evolved over a million years to fight any foreign body that enters its system. Which is exactly what they are – a foreign body. Their task, he professes (remember, he’s a professor) is almost impossible. Little does Grant know, it’ll be more impossible than he thinks, as later he’ll find out… they’re not the only foreign body inside of Megan.

Reading this script is like reading one giant set of challenges. This is the kind of thing, if you break into his business, you’ll be tasked with figuring out. You have an idea that doesn’t quite work. What are you going to bring to the table to make it work? Fantastic Voyage’s problem, through no fault of any of the writers here, is a story that reads like something that could be tackled in an episode of a Saturday morning cartoon. A small submarine flying through the body. Oh no, watch out for the white blood cells!

It’s just not easy to give this the weight to stand toe to toe with all the other big movies out there. Damon Lindelof was recently interviewed about writing summer movies, and he pointed out that when you’re spending 150+ million on anything, the stakes have to be saving the world. That’s this draft of Voyage’s biggest problem. The only thing that really seems to be at stake here is this woman (the world is sorta at stake, but it’s unclear how).

Don’t get me wrong. That can work if we really love this woman and really want to see her and Grant get together in the end. But we barely know Megan (we only got to see her in that first scene) and we definitely don’t know her and Grant together outside of Grant mentioning it a few times, so we’re not emotionally invested in them getting to happily ever after.

The thing is, that’s the angle I would’ve taken too. There has to be an emotional attachment between the saver and the savee. But since we never saw that attachment, it’s hard to care. And this is a screenplay problem screenwriters all over the world face. How do you show that attachment without grinding the story to a halt? Do you start in the past, showing the two together? That means the script starts slow. Do you add flashbacks throughout? That’s hard to do without feeling on-the-nose and cheesy. So I sympathize with the writers here.

I will say that there’s on easy switch they could’ve done that would’ve made this way better. Megan can’t be asleep. She’s got to be in her own pressure-cooker of a situation while these guys are inside of her. That way, you have a dual-storyline going on. You jump inside her, they’re trying to defuse the chips, you jump out of her, she’s running from some people, or trying to accomplish her own mission (which might involve saving millions of people from the Alliance – now you have your “save the world” scenario). Having Megan in a coma the whole time was a missed opportunity.

The Fantastic Voyage script was also unique in that it was one the few times where I realized the world was beyond the realm of description. Well, maybe not beyond, but as these guys tried to describe the inside of the human body, it was overwhelming. And I was never quite sure what I was looking at. I just imagined a bunch of globbery red stuff with veins shooting everywhere. I rarely encounter that situation where the world is just so complex, it can only be shown onscreen (unless you want to write a book of description) and that hurt the read, because whenever we were chasing or being chased or going anywhere, I only had a vague visual sense of what was going on.

Finally, I think there was too much plot and not enough character development here. This is ANOTHER thing writers deal with when writing big-budget films. These films demand lots of plot and action to happen, so that’s where most of the focus goes. But we have to remember that if we don’t care about the characters, the plot doesn’t matter. The big issue here is that the most important relationship in the movie (Grant and Megan) isn’t even explored because there’s no way for them to communicate. And the rest of the characters were more “plot-mover” types. There to do shit, but not develop. I would’ve liked to have seen more development.

Fantastic Voyage is an idea fraught with challenges. I will say, though, that if James Cameron directed this, I would see it. Because you know he’d do two years of researching the human body and learning every single little thing there is to learn about it. Hell, he’d probably finish sequencing human DNA and wipe out a few cancers while he was at it. But the attention to detail he would give to this would make it worth watching. As far as THIS old draft of the script though, it wasn’t quite there. Which is probably why they’re still developing it.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: As you make your way into this industry, you’re going to be asked to pitch your take on ideas a lot. I think it’s important to have a bold take when you walk into a pitch, an angle others haven’t thought of. That’s what Jaffa and Silver did with “Apes.” Everyone else was pitching the obvious versions of that story. They wanted to focus on one ape and his journey, even though he didn’t speak for 99% of the movie. That was bold. The take everyone has for Fantastic Voyage is pretty obvious and I think that’s what’s keeping it from becoming a hot project. This needs a hot take. What about you guys? What would your take be?

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama

Premise: A Maine-based lobster fishing family who has fallen from grace, finds a chance at redemption when their old fishing boat comes back up for sale.

About: Every year, AMC takes its six best potential scripts and allows their writers/creators to pitch them and the entire show in a more extensive format, via visual aids, or whatever else they can think of. Whoever still looks good after that gets a show on the air. This sounds like a good approach, but doesn’t always work. One of the shows to come out of this format was Low Winter Sun, the depressing took-itself-too-seriously bore fest. The strangely titled “F/V Mean Tide” (I don’t know why you’d put a forward slash in a title. – Unless “F/V” stands for “final version” maybe??) is another one of those scripts. You’re probably wondering, why did you pick this to review, Carson? Well first of all, I trust AMC. They have their misses (as documented above) but as far as alternative TV series, they’re right up there with HBO and Netflix. With that said, their line-up is getting old, with the exception of maybe The Walking Dead, which could conceivably go on forever. So they need some new juice in the fridge. Writer Jason Cahill has written for Fringe, The Sopranos and ER.

Writer: Jason Cahill

Details: 58 pages – 3rd draft

George Clooney to play the father? Hey, more and more film guys are moving to TV and it’s a great role. Why not??

George Clooney to play the father? Hey, more and more film guys are moving to TV and it’s a great role. Why not??

One of the frustrating things about reading so much material is getting bored with so much material. Everybody’s pretty much writing the same stuff with the same characters with the same plots. It starts to depress you actually! But after awhile, you start to realize that you’re part of the problem. If all you’re going to read are sci-fi scripts and thrillers and rom-coms, you’re not going to find much variety in the writing. If you want to experience something unique, you have to take chances, read some offbeat things that don’t necessarily sound like slam dunks. Personally, I’ve never heard of a script based on lobster fishing, so I said, “Hell,” why not.

“Mean Tide” follows 29 year-old Matt Aegis, a lobster fisherman with a complicated past. When we meet Matt, he’s relegated to pulling up traps for an asshole captain whose alcoholism is so bad, he still tries to navigate his boat when it’s tied up to the dock.

For this reason, Matt wants his own boat to captain, but boats cost money, and he doesn’t have much. It just so happens, however, that one of the oldest fisherman in town is retiring and selling his boat. The boat is ancient and doesn’t come close to the technology on these new boats (that find their fish via fancy satellites), but Matt has a secret plan for finding lobster that the most cutting edge technology in the world can’t compete with. We’ll get into that later.

The irony is, the boat Matt wants to buy actually belonged to his father, who lost it because of some fucked up criminal thing that happened in the past (the thing that no one shall talk about!). Before that, Matt’s family was looked at as Gods. Their great great grandfather practically built the town. But nowadays, those looks of awe have turned sideways, to the point where the only people the owner of the boat refuses to sell to are, you guessed it, Matt and his family!

Now it wouldn’t be a show without a few pretty ladies to look at and we got ourselves some doozeys. Even though Matt’s taken with the local tomboy hottie, he gets swept up in the arrival of a mysterious new siren of a female who oozes sex. It’s like if Kate Upton and Kim Kardashian decided to have a baby. All the other fisherman warn him, however, that this wannabe mermaid is well known for banging men and making them disappear. If he knows what’s good for him, he’ll keep his pincers in his pants. Matt lives life on the edge of the bow though, so the pincers come out.

So what’s Matt’s ultimate plan if he does get that boat? Ghost Trees. It’s a spot out in the ocean that’s a shoal forest. Lobsters are hanging out there in the thousands. But everyone’s too scared to go near it, less the shoals rip their boats to shreds. Not Matt though. He’s the only man willing to take the risk. First Matt’s got to get the actual boat though, and not be chomped up by this femme fatale. If he can do that, he and his family just might rise to prominence again.

So did the big risk pay off? Did reading a script/pilot that I would normally never read result in reading euphoria?

Not exactly. But that doesn’t mean I regret reading Mean Tide.

Here’s the thing I continue to be reminded of with scriptwriting. In the end, it’s all about the characters. It doesn’t matter what you’re writing about. As long as the characters are interesting, you’ll pull the reader in. There are some catches to that, of course. You have to create an idea that continually puts those characters in interesting situations so that the characters will stay interesting. But for the most part – it doesn’t matter what the setting or idea is. If you write great characters, people will enjoy your script (or movie, or TV show).

Here’s the caveat though. Nobody’s going to find out about your great characters unless people want to read your script (or watch your movie, or see your TV show) in the first place. This is where concepts come into play. You have to have somewhat of an interesting concept to trick people into checking out your show (or movie, or script) in the first place so that they can fall in love with those characters and keep watching.

This wasn’t always the case. TV didn’t used to be like film, where concept is king. You could focus a show on something simple, like the ER section of a hospital, and you’d have a hit. But I think that’s changing. Mainly because TV is getting so big and all this new material is flooding into the medium. With all that material, the only way to stand out is similar to the way writers stand out in the feature world – a cool concept. It’s why shows like Extant and The Blacklist and The Walking Dead are getting picked up. Even Breaking Bad has a nice little ironic hook (a dying chemistry teacher is forced to cook meth to provide for his family).

To that end, you’re going to get a lot of gun-shy executives when they’re faced with shows like “Mean Tide.” It is fairly interesting subject matter. And the characters are deep and multi-faceted. But it basically comes down to that age-old screenwriting truism: The smaller the hook, the better the writing has to be. If you’re going to write about families in suburban America (zero hook) the writing has to be perfect for the movie to be made (American Beauty). The hook here is kind of small – lobster fishing – and I’m not sure the story is good enough to make up for that.

Don’t get me wrong. There’s a lot of good here. I love how the pilot is structured like a feature (Matt’s got 3 days to come up with the money to buy the boat — goal! stakes! urgency!). I love how the family is presented as an underdog, so we immediately like them. I liked how nobody was perfect (Matt’s dad has a wayward eye and is unloving towards his son). I liked the conflict (every single relationship was steeped in some kind of history, making for plenty of conflict and subtext). And I loved this looming dangerous gold mine that was the Ghost Trees. I loved that everybody else was afraid of it except for our main character. Made him heroic and kept up the suspense, as we wanted to see if he’d be able to navigate it and reap its rewards at the end (the dangling carrot that kept us reading til the end).

But the story never really built enough. It kind of stayed at an even keel. And there was this annoying voice over from Matt that ran throughout the entire script that was totally unnecessary. It was one of those voice overs where the main character is trying to sound thoughtful and philosophical as he describes the events and people and history of the town. But it comes off as pretentious. I hate voice over that, if you cut it out, wouldn’t have any bearing whatsoever on the story. And that’s the kind of voice over this was. If you got rid of it, nothing changed. That’s the very definition of unnecessary.

There’s no question Cahill is a good writer but this pilot is missing something and I’m having a tough time figuring out what that is. Is it that the concept’s too small? Are we missing a twist or a big plot point to give the middle section a jolt? That may be it because I was never really surprised by where the script went. I felt like I was ahead of it. As a writer, it’s your job to be ahead of the reader, not the other way around. But anyway, while this was a strong pilot, until that something extra is found, it probably won’t be ready for television.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: To find a goal that results in the story for your pilot, create a problem for your main character. From problems emerge goals. So here, Matt is frustrated as shit with his current job as a 3rd Fisherman on some trawler boat. That’s his problem: he doesn’t want to be doing this anymore. So when a new boat comes up for sale, he sees an opportunity to fix that problem. His goal (which emerges from the problem) is to get the money needed to buy the boat within 3 days. The problem leads to the goal which leads to the framework (or structure, or blueprint) of your story.

What I learned 2: AMC’s “Top 6 scripts” approach reminded me that every production house or studio or network is basically a writing contest. You’re entering their contest and the winner gets to be on the air (or in a movie theater). The difference between this contest and contests like the Nicholl or Page, is that instead of competing against amateurs, you’re competing against pros, writers who understand story and characterization and dialogue and structure. The competition is a LOT LOT better, so you really have to knock it out of the park if you want to “win” that contest.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A sheep herder in the old west falls for a woman who’s married to the biggest gang leader in the region.

About: This is Family Guy (and Ted) creator Seth MacFarlane’s new movie. Last year’s Oscar host is taking his new film one step further from Ted and adding “lead actor” to his ever evolving resume. The film will co-star Charlize Theron, Liam Neeson, Amanda Seyfried, and Neil Patrick Harris. For those of you frustrated by all the recent successes I cover being of Ivy League pedigree (it seems like every other pro writer I review these days graduated from Harvard), you’ll be happy to hear that MacFarlane (whose fortune is measured at 150 million dollars over at Celebrity Net Worth) slummed it up at the Rhode Island School of Design before moving to Hollywood. Hey, if someone from Rhode Island can make it here, anybody can.

Writers: Seth MacFarlane and Alec Sulkin & Wellesley Wild

Details: 125 pages (1st draft)

I’ll be the first to admit, I did not think Ted was going to be a hit. Only afterwards did I realize the power of Seth MacFaralane, the multi-talented cartoonist, host, comedian, and now actor. It appears MacFarlane is now going the Trey Parker/Matt Stone route, evolving his cartoonist career into an acting one. Of course, that didn’t work out too well for the South Park duo (Baseketball was a jumbled mess of a concept that become too goofy for its own good, resulting in us never seeing Matt and Trey onscreen again), but MacFaralane has a 250 million dollar hit on his resume, which gives him a little more cache going into “West.”

That’s not to say all is swell in the land of this decision. MacFarlane looks really odd in the trailers, sort of like a wax museum character (the man never seems to have a hair out of place) set against a gaggle of much more authentic looking chess pieces. But I do have to give it to him as a writer-director. He’s come in to the movie space taking big risks (a talking teddy bear movie and a western comedy??), something no other comedy folks in Hollywood are really doing. You have to respect that. Let’s see what his latest script is all about.

It’s the olllllld West. 30-something Albert Stark is the world’s worst sheep herder. How bad? Occasionally his sheep will end up on the roof of his house. How that’s even possible, no one knows. Lucky for him, he’s got a hot girlfriend in Louise, even if she does treat him the way Kate treated Jon in Jon & Kate Plus 8. But after Albert backs down from a duel, Louise has had enough of his pussy ways and dumps him.

Bummed out, Albert tries to get back on the horse (apropos, since I think this is the era where that phrase was actually born!), but dating back in the Old West isn’t like dating today. Eager parents are pushing their 12 year-old daughters on you (which results in one of the most awkward dates you’ll ever see onscreen). Lucky for Albert, a sharp-tongued energetic woman named Anna arrives in town and the two immediately become friends. They decide to pretend to go out to make Louise jealous so Albert can get her back.

Unfortunately, Louise has moved on and is now dating the extremely arrogant town mustachier, a well-groomed fellow named Foy. As much as Albert would like to challenge old Foy, the reality is that he’s a coward. It’s why he lost Louise in the first place and it’s why he’ll never have a woman like her again. Not so, says Anna! She’ll teach him how to shoot, and that way he can duel against Foy and win back the girl of his dreams.

Oh, but there’s one last problem. Anna isn’t telling the whole truth. She’s married to the most ruthless gangster in all the land, and he’s on his way to town RIGHT NOW. The cowardly Albert will not only have to take down his nemesis, Foy, but also the Billy The Kid of his era. Will he be able to do it? And even if he does, can he still avoid one of the million other ways to die in the West? We shall see!

“Million Ways To Die” was surprisingly good, especially for a first draft (although “labeled” first drafts are always tricky to measure. It might mean it was the first draft given to the studio. But it could’ve been the 10th draft they worked on before that point). But here’s what I liked about this script, and it’s a lesson screenwriters everywhere should jot down.

“Million Ways to Die” allowed us to take comedy tropes we’ve seen a million times before, and make them fresh. Think about it. How many comedies have the main character getting dumped by his girlfriend within the first 15 pages? 8 billion? 20 trillion? A lot, right? Which is why they all feel so cliché and lame.

But how many WESTERNS have been made where the main character gets dumped by his girlfriend in the first 15 pages? Not many, right? Welcome to the beauty of changing up the time and setting of your story. You can use all those typical tropes we’ve seen a million times before, and they all come off as fresh and new.

When Anna enters the picture, we even get the, “Pretend to be together to get the ex-girlfriend back but actually fall in love with each other along the way” trope. God, am I sick of seeing that in garden-variety comedies. But here it feels unique and fun. Change the time and setting of your story and thousands of cliché jokes become available to you, because in this new setting, they don’t feel cliché anymore!

MacFarlane (and his co-writers) seem to understand character better this time around, too. Albert has a clear flaw – he’s a coward. And that flaw is constantly being challenged, allowing the writers to explore character. What I mean by that is, when you have a character flaw, you want to constantly give your character opportunities to overcome that flaw and fail (until the very end, of course). So MacFarlane will have a big bar fight break out – allowing Albert a chance to be brave, to fight. Instead he ducks out, still stuck in his cowardice ways.

We even have some dramatic irony working to strong effect here. We know Anna is a gangster’s wife. That he’s coming sooner or later. So we know this relationship, and Albert, are doomed! We’re just waiting for the shit to finally hit the fan. What’s great about this is how seamlessly it ties into Albert’s flaw. If he wants Anna at the end, he’s going to have to overcome his biggest weakness – his cowardice. He’ll have to defeat the most fearless villain to do it.

I think what surprised me most about “Million” is how much I cared. I will contend to the end that comedy stops being funny once you stop caring about the characters. You can write the most genius funny scene ever, but if we stopped giving a shit about your characters 30 minutes ago, you’ll be lucky if you get a chuckle out of us.

But let’s not be foolish. You still gotta bring the funny for a comedy to work, and MacFarlane does. Probably the best running gag was Edward, Albert’s best friend, who’s dating a whore at the local whorehouse. He’s in love with her despite her coming home every day regaling in her day’s work, some of the most raunchy, horrifying sexual experiences you can possibly imagine. I’m talking worse than anything you can find on the internet. And yet, because she and Edward are Christian, she doesn’t want to sleep together until they get married. When Edward suggests lying together one night (not doing anything, just lying in the same bed), she is beyond appalled. “We’re Christian!” she reminds him. And then also reminds him she has an anal appointment at 5:30.

I honestly have no idea how this movie is going to do. That’s the problem when someone takes a chance. You don’t have as much comparative data to work with to predict box office. Plus, Seth MacFarlane in a lead role is a total wildcard. Who knows how audiences are going to respond to that. What I can tell you is that this was a fun and surprisingly well-written screenplay.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The flaw you give your main character doesn’t have to be inventive. Flaws are often simple universal traits we’re all familiar with. One of the best ways to come up with a flaw is to identify your setting and look for a flaw that seems logical to explore within that setting. The West was big on machismo. So it makes sense to explore a cowardly hero. If I were to write a movie about the financial world, my main character’s flaw would probably be associated with greed. If I were to write a movie about racism, my main character’s flaw might have something to do with ignorance. It’s almost too simple, but that’s how flaws work.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Adventure

Premise: (from writer) When his war-hero grandfather dies, a young man returns home to collect his inheritance — an audio cassette tape of old bedtime stories — but discovers the tape also holds a dark secret that a sinister group of agents wants back at any cost.

Why you should read: (from writer) Because fun, genuine adventure movies for kids and teenagers — without superheroes — are a rare thing these days and I want to mount a comeback. This one’s filled with action, humor, romance and intrigue, dastardly villains and honest heroes. It’s not perfect, but I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it (and re-writing it, and re-writing it), and I would love everyone’s help in making it even better.

Writer: Matthew Merenda

Details: 115 pages

Is Matthew Merenda right? Are we suffering from a lack of big non-super-hero movies? I’d say, moist sointenly. That may be the most obviously obvious statement of the new millennium. Therefore, after Boom Box blew away the competition a couple of weeks ago in Amateur Offerings, I wondered, “Has this writer finally found the answer to this problem?”

But before we tackle that, Merenda’s question inspired one of my own. How come we haven’t had more movies like Indiana Jones? Big films with unique cool characters not based on intellectual property. Cause when you look at Raiders, it was such a simple idea! Professor dude is secretly a tomb raider in his spare time. Hollywood would have you believe that every single character we see in the movies has already been thought up in book form, comic book form, or video game form. They make it seem as if it is IMPOSSIBLE to write one of these characters on spec.

That begs the question. Is it impossible? Or is it just that spec screenplay writers don’t put in the same effort in creating these characters and these stories as a video game team, or a novelist, or a comic book company? Personally, I’m torn on the issue.

Not that today’s script is a Raiders clone or anything. But it’s an original adventure idea. So what’s it about? Jack Walsh was this big international agent spy dude back in the 50s. He used to save the world on a daily basis, in particular from an evil nasty bastard named “Von Krom.” Jack and Von Krom would regularly get into those situations you saw on the old Batman TV show where they entered a big room with some sort of dangerous giant weapon being prepped and Batman would have to stop the villain from using said weapon before it killed him and everyone else in the world.

Or at least… that’s what Jack Walsh tells his grandchildren, when he regales them with bedtime stories every evening. And according to Jack, he came out victorious, eventually killing Von Krom so that the world would never have to fear him again.

Until the world had to fear him again. That’s right, 60 years later, Von Krom returns! Older but wiser, he introduces a couple of bullets to Jack’s head, making it look like a suicide, and starts his plan to take over the world.

Off in the big city, the now grown-up older of Jack’s two grandchildren, 24 year old failed musician Mike, heads back to attend the funeral, only to be approached by his teenage brother, Max, who believes that Jack did not commit suicide, but was rather murdered!

The two find an old audio cassette tape from Gramps, which, while masquerading as one of his stories, actually has some pulsing sounds in the background that may or may not contain a secret message! As the two begin seeking clues, Max excited, Mike unwilling, they find that all their Grandpa’s stories were true, Von Krom is still alive, and he’s planning on vaporizing everyone in the state with a secret weapon by the end of the evening. Can they stop him in time? Or will this AARP Villain inspire other octogenarian baddies everywhere with his Giantus Killus Opus?

So was Boom Box worth turning up the volume for? Or should this box of metal and plastic head back to its 80s glory days?

Here’s the weird thing about the Amateur Offerings experiment. The script that wins every week almost always LOOKS and FEELS like a script. It’s someone who knows how to do things like keep text sparse, introduce their hero in a compelling way, structure a script. Typically, that takes about 2-3 years to master. So if you’re entering Amateur Friday with 3 years of experience, you’ll often finish in the top 1 or 2, just off your experience and knowledge alone.

But just being proficient in screenwriting isn’t enough. I know I hammer this over your heads all the time, but screenwriting is about telling a story. It’s not about how well you can write. Or how well you understand the technical merits of the craft. That stuff is expected in this profession.

Boom Box is off in its storytelling for a few reasons. Let’s start with the main character, Mike. The guy is a total bummer! He’s so down on himself, so down on everyone else, always negative, never wants to do anything. It’s strange, because Jack Walsh (the grandfather) was awesome! I actually loved the guy, and when I first started reading the script, I thought Merenda was going to try something new and write a senior citizen action-comedy adventure. Admittedly, I don’t know if that movie could get made, but it certainly would’ve made the script stand out more and get more attention, particularly because Jack was such a great character.

As soon as Mike entered the picture though, the entire energy of the script dropped. This is one of the hard parts about screenwriting. I understand WHY Merenda did what he did. By creating a negative hero, he creates resistance, conflict, as well as making for a more complex person. Mike doesn’t believe in his grandfather’s stories like his brother, which allows him to arc over the course of the story and finally believe. That looks good on the stat sheet, but if we’re annoyed by your hero, none of it matters. We’ll check out before we get to experience any of that change. So the first thing I’d do here is make Mike more interesting, give him more personality, not make him such a downer.

Also, I thought the story moved too slowly. It’s crazy. I can take two pieces of information (“Adventure film” and “116 pages”) and before I’ve even read the first page, know something is wrong. Adventure films must move! 105 is a much more comfortable page length for a script like this. So I already knew the script probably meandered in places.

I know what you’re saying. “Carson! You can’t tell that without reading the script!” I admit that this isn’t the case ALL the time. But it usually is. And there it was. We didn’t get to our heroes (the brothers) listening to this tape and going on their adventure until page 35. You don’t need 35 pages to set up the first act. And that’s exactly how it felt while I was reading it (“Man, this is developing really slowly”). If Merenda had had his first act turn where it should’ve been in an action script, page 25, well, that’s your extra ten pages right there! Fix that and you’re down to 105.

The rest of the script was competent but still had problems. I don’t want to downplay what Merenda did here. This looks and feels like a script. But again, I think the storytelling could’ve been more creative and moved quicker. I mean when I see “adventure” as the genre, and then we set up the story with an international super-agent fighting crime all over the world, I guess I expected this adventure to be more than two kids running around a tiny town. It felt too small.

Boom Box is kind of like an 80s mix-tape. It’s got some good songs on it. But then you’ll hit a few tracks that you wish weren’t on there. I think the tape, err, script, has potential though. Start with Mike. Give the guy some life. Then get to the story a little quicker. And, if you can find a way to do so, expand the scope of the story. This last point is the one I’m least sure about. I get the feeling Merenda was going for a sort of “Goonies” vibe. So maybe the readers will argue with me on that one. But to me, it feels too small. If you can tackle those three problems, Boom Box is going to sound a lot better.

Script link: Boom Box

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t describe your female lead as: “classically beautiful.” I see this description in every other script that I read. Come on guys. You’re writers. Your job is to give us your own unique take on everything. If you’re writing exactly what everyone else is, how are you going to distinguish yourself?

Gone Girl had a disappointing final act. So Fincher had author Flynn rewrite it for the movie. Will it save the film?

Gone Girl had a disappointing final act. So Fincher had author Flynn rewrite it for the movie. Will it save the film?

In the five years since this site began, it’s hard to believe that I STILL haven’t written an article about the third act. I think it’s because the third act is kinda scary. It’s easy to set up a story. The middle act is tough, however I’ve written a couple of articles demystifying the process. But with final acts, it feels like every one is a little different. They’re sort of like their own little organisms, evolving and changing in indefinably unique ways, packed with previously established variables that are constantly fighting against one another, and it’s hard to bring all of that together in a streamlined package.

Blake Snyder does a really good job breaking down the third act, and his methods are a good place to start, but what I’ve found is that his approach mostly applies to comedies and romantic comedies, where the audience is aware of the exaggerated structure of the moment (hero loses the girl, is at his lowest point) but doesn’t mind. They come to see these movies because they like laughing and seeing the guy get the girl, so they don’t need some genius plot point to keep them invested.

With that said, I think it’s a good idea to have a baseline approach to your third act. It’s the same thing as if you’re building a house. You want to get the blueprints in order. But you still need to keep the option open of adding a breakfast nook over here, or moving the kitchen over to the other side of the main room. So here’s how a prototypical third act should be structured. It doesn’t mean that your act should be structured the same way. It just means it’s a starting point.

THE GOAL

Without question, your third act is going to be a billion times easier to write if your main character is pursuing a goal, preferably since the beginning of the film. “John McClane must save his wife from terrorists” makes for a much easier-to-write ending than “John McClane tries to figure out his life” because we, the writer, know exactly how to construct the finale. John McClane is either going to save his wife or he’s going to fail to save his wife. Either way, we have an ending. What’s the ending for “John McClane tries to figure out his life?” It’s hard to know because that scenario is so open-ended. The less clear your main character’s objective (goal) is in the story, the harder it will be to write a third act. Because how do you resolve something if it’s unclear what your hero is trying to resolve?

THE LOWEST POINT

To write a third act, you have to know where your main character is when he goes into the act. While this isn’t a hard and fast rule, typically, putting your hero at his lowest point at the end of act two is a great place to segue into the third act. In other words, it should appear at this point in the story that your main character has FAILED AT HIS/HER GOAL (Once Sandra Bullock gets to the Chinese module in GRAVITY, that’s it. Air is running out. She doesn’t understand the system. There are no other options). Either that, or something really devastating should shake your hero (i.e. his best friend and mentor dies – Obi-Wan in Star Wars). The point is, it should feel like things are really really down. When you do this, the audience responds with, “Oh no! But this can’t be. I don’t want our hero to give up. They have to keep trying. Keep trying, hero!” Which is exactly where you want them!

REGROUP

The beginning of the third act (anywhere from 1-4 scenes) becomes the “Regroup” phase. This phase often has to deal with your hero’s flaw, which is why it works so well in comedies or romantic comedies, where flaws are so dominant . If your hero is selfish, he might reflect on all the people he was selfish to, apologize, and move forward. But if this is an action film, it might simply mean talking through the terrible “lowest point” thing that just happened (Luke discussing the death of Obi-Wan with Han) and then getting back to it. Your hero was just at the lowest point in his/her life. Obviously, he needs a couple of scenes to regroup.

THE PLAN

Assuming we’re still talking about a hero with a goal, now that they’ve regrouped, they tend to have that “realization” where they’re going to give this goal one last shot. This, of course, necessitates a plan. We see this in romantic comedies all the time, where the main character plans some elaborate surprise for the girl, or figures out a way to crash the big party or big wedding. In action films, it’s a little more technical. The character has to come up with a plan to save the girl, or take down the villain, or both. In The Matrix, Neo needs to save Morpheus. He tells Trinity the plan, they go outfit themselves with guns from the Matrix White-Verse, and they go in there to get Morpheus.

THE CLIMAX SCENE

This should be the most important scene in your entire script. It’s where the hero takes on the bad guy or tries to get the girl back. You should try and make this scene big and original. Give us a take on it that we’ve never seen in movies before. Will that be hard? Of course. But if you’re rehashing your CLIMAX SCENE of all scenes?? The biggest and most important scene in the entire screenplay? You might as well give up screenwriting right now. If there is any scene you need to challenge yourself on, that you need to ask, “Is this the best I can possibly do for this scene?” and honestly answer yes? This is that scene!

THE LOWER THAN LOWEST POINT

During the climax scene, there should be one last moment where it looks like your hero has failed, that the villain has defeated him (or the girl says no to him). Let’s be real. What you’re really doing here is you’re fucking with your audience. You’re making them go, “Nooooooo! But I thought they were going to get together!” This is a GOOD THING. You want to fuck with your audience in the final act. Make them think their hero has failed. I mean, Neo actually DIES in the final battle in The Matrix. He dies! So yeah, you can go really low with this “true lowest point.” If the final battle or confrontational or “get-the-girl” moment is too easy for our hero, we’ll be bored. We want to see him have to work for it. That’s what makes it so rewarding when he finally succeeds!

FLAWS

Remember that in addition to all this external stuff that’s going on in the third act (getting the girl, killing the bad guy, stopping the asteroid from hitting earth), your protagonist should be dealing with something on an internal level as well. A character battling their biggest flaw on the biggest stage is usually what pulls audiences and readers in on an emotional level, so it’s highly advisable that you do this. Of course, this means establishing the flaw all the way back in Act 1. If you’ve done that, then try to tie the big external goal into your character’s internal flaw. So Neo’s flaw is that he doesn’t believe in himself. The only way he’ll be able to defeat the villain, then, is to achieve this belief. Sandra Bullock’s flaw in Gravity is that she doesn’t have the true will to live ever since her daughter died. She must find that will in the Chinese shuttle module if she’s going to survive. If you do this really well, you can have your main character overcome his flaw, but fail at his objective, and still leave the audience happy (Rocky).

PAYOFFS

Remember that the third act should be Payoff Haven. You should set up a half a dozen things ahead of time that should all get some payin’ off here in the finale. The best payoffs are wrapped into that final climactic scene. I mean who doesn’t sh*t their pants when Warden Norton (Shawshank spoiler) takes down that poster from the wall in Andy Dufresne’s cell? But really, the entire third act should be about payoffs, since almost by definition, your first two acts are setups.

OBSTACLES AND CONFLICT

A mistake a lot of beginner writers make is they make the third act too easy for their heroes. The third act should be LOADED with obstacles and conflict, things getting in the way of your hero achieving his/her goal. Maybe they get caught (Raiders), maybe they die (The Matrix), maybe the shuttle module sinks when it finally gets back to earth and your heroine is in danger of drowning (Gravity). The closer you get to the climax, the thicker you should lay on the obstacles, and then when the climactic scene comes, make it REALLY REALLY hard on them. Make them have to earn it!

NON-TRADITIONAL THIRD ACTS (CHARACTER PIECES)

So what happens if you don’t have that clear goal for your third act? Chances are, you’re writing a character piece. While this could probably benefit from an entire article of its own, basically, character pieces still have goals that must be met, they’re just either unknown to the hero or relationship-related. Character pieces are first and foremost about characters overcoming their flaws. So if your hero is selfish, your final act should be built around a high-stakes scenario where that flaw will be challenged. Also, character piece third acts are about resolving relationship issues. If two characters have a complicated past stemming from some problem they both haven’t been able to get over, the final act should have them face this issue once and for all. Often times, these two areas will overlap. In other words, maybe the issue these two characters have always had is that he’s always put his own needs over the needs of the family. The final climactic scene then, has him deciding whether to go off to some huge opportunity or stay here and takes care of the family. The scenario then resolves the character flaw and the relationship problem in one fell swoop! (note: Preferably, you are doing this in goal-oriented movies as well)

While that’s certainly not everything, it’s most of what you need to know. But I admit, while all of this stuff is fun to talk about in a vacuum, it becomes a lot trickier when you’re trying to apply it to your own screenplay. That’s because, as I stated at the beginning, each script is unique. Indiana Jones is tied up for the big climax of Raiders. That’s such a weird third act choice. In Back To The Future, George McFly’s flaw is way more important than our hero, Marty McFly’s, flaw. When is the “lowest point before the third act” in Star Wars? Is it when they’re in the Trash Compactor about to be turned into Star Wars peanut butter? Or is at after they escape the Death Star? I think that’s debatable. John McClane never formulates a plan to take on Hanz in the climax. He just ends up there. The point is, when you get into your third act, you have to be flexible. Use the above as a guide, but don’t follow it exactly. A lot of times, what makes a third act memorable is its imperfections, because it’s its imperfections that make it unpredictable. If you have any third act tips of your own, please leave them in the comments section. Wouldn’t mind learning a few more things about this challenging act myself!