Congratulations to Poe’s “The Man of A Few Words,” which won this weekend’s Dialogue Short Script Mini-Contest. He wins a First 10 Pages Consultation from me. Poe’s a longtime kick-ass commenter so make sure to congratulate him!

Genre: Black Comedy

Premise: (from Black List) When an out-of-work divorced mother stops taking the court-ordered medication that made her feel like a zombie, her brazenly immoral, fifteen-year-old imaginary friend appears to help get her life back on track.

About: You may not have heard of Turner Hay yet. He broke onto the scene a few years ago, taking 3rd place (with a different script) in the Samuel Goldwyn Writing Awards, which is a big deal. Past winners include Eric Roth and Francis Ford Coppola, and they always have great judges for the competition (Billy Wilder, James L. Brooks, and Denzel Washington). Hay then got on the bottom half of the 2016 Black List with this script.

Writer: Turner Hay

Details: 111 pages

I am done being Complainer Carson for the week!

I am not going to complain about Academy Award winning screenplays that don’t deserve Oscars. Nope. Not gonna happen anymore. I am putting Complainer Carson on the shelf next to the salt and pepper and vinegar. It’s not going to be a part of this meal.

Instead, I am only going to regale you with positive stories, affirmations if you will. For example, did you know that Best Picture winner Moonlight only had a budget of 1.5 million dollars? That’s the equivalent of showing up to McDonald’s and trying to buy an entire meal for a nickel. It’s a ridiculous accomplishment for a film with that tiny of a budget.

Just for comparison, La La Land? Which, itself, is considered to be “low-budget” by Hollywood’s standards. Their budget was 30 freaking million dollars.

Oh, and Manchester by the Sea? Okay, yes, I did not like it, true. But you know what I did like? Kenneth Lonergan’s first film, You Can Count On Me. Great film. So I know the dude can write. Which makes it even more confusing why Manchester was so ba— CARSON! NO! NO, COMPLAINER CARSON! You’re not allowed here. Back on the shelf!

Before I get into any more trouble with my evil twin, let’s check out today’s screenplay and pray that it’s good enough to keep my weekly positive buzz going…

37 year-old Ivy Lydecker suffers from schizophrenia. And it’s not good, folks. She kind of may have killed her mother 11 months ago. Who was also crazy by the way. And the courts decided there was enough wiggle room in their scuffle that Ivy is allowed to live her life, as long as she takes a little blue “make the voices go away” pill every day.

Unfortunately, that pill makes Ivy a zombie. And when you’ve got a teenage son to take care of and an ex-husband who’s trying to permanently wrestle him away from you, being dead to the world isn’t ideal.

And so Ivy stops taking her pill. Which is how we meet Chloe, her cool-as-shit 15 year old imaginary best friend. The two clearly have a storied past, and Ivy would like nothing more than for Chloe to disappear. But it’s clear that no-pill and yes-Chloe are a package deal. You don’t get one without the other.

Chloe jumps into action, helping Ivy with her goal: prove to the courts she’s capable of taking care of her son. So Ivy gets a new job at a Securities Exchange, she starts dating a hot new restauranteur who’s a decade younger than her. She’s moving, she’s shaking. Things are happening in her life.

Oh, until that guy she’s dating ends up dead. And since Ivy already has a kind-of murder in her portfolio, the police want to know just how much she and this dude hung out. As the mystery thickens, Ivy’s new perfect life starts to crumble, to the point where she has to make a permanent choice. Keep living this wild lifestyle with Chloe, or go full zombie on the blue pill forever.

Bitter Pill-like scripts are interesting case-studies.

On the one hand, they do well on the Black List. The Black List likes inventive black comedies with fucked up main characters. Even more so if they’re women. There was a similar great script a couple of years ago called, “Cake.”

On the other hand, these films never do well at the box office. Even by low-budget indie standards, they’re tough sells. Cake, for example, made all of 2 million dollars, with a well-known actress in the lead role.

But going back to the first hand, these scripts are great career starters, regardless of whether the movie does well or not, as they display a strength in the one area Hollywood needs screenwriters for – the creation of compelling memorable characters.

Remember that suits can come up with concepts. They can come up with plots. The better ones can even beat out an outline. But nobody can write great characters except for good screenwriters. So when you break into the industry with one of these scripts, you prove that you have a highly valuable skill. You are the Liam Neeson of screenwriting.

So what is it that makes Ivy a strong character? For one, she’s battling something. Just by introducing a character who is battling an inner conflict, you’ve made a character that’s more interesting than most of the characters out there.

Step two is that the character is sympathetic, but not in a forced way. This is an important one so pay attention. Ivy has a son that’s being taken away from her. You’d be hard-pressed to find someone who wouldn’t want to root for a mom that’s losing her son.

However, that’s pretty much the only box that’s checked on Ivy’s sympathy card. Ivy is selfish. Ivy is self-serving. Ivy is malicious at times. So because we have aspects of Ivy’s personality that are both good and bad, we don’t feel like we’re being pandered to. It’s that nuance that gives the character more of a “realistic” quality.

I remember reading a review for Paul Blart: Mall Cop when it came out. The reviewer pointed out that the first half hour of the film was dedicated to giving Paul Blart over a dozen sympathetic qualities to MAKE SURE that the audience loved him. That’s what you don’t want to do. You want to balance it out.

Creating nuance with just the right amount of sympathy, combined with some inner conflict – that’s the beginnings of a great character there.

And another way to build up a character is to make their inner conflict actually matter. Or, to use a well-known screenwriting term, add HIGH STAKES to it. So in the case of Ivy’s schizophrenia, there are real stakes if it’s found that she’s not taking her pills. She could lose custody of her kid.

And the reason that matters is because when we see her around other people and Imaginary Chloe is chatting away, we know that if Ivy breaks the ruse and talks back, she’s done. Her whole world will come crumbling down. This adds tension and uncertainty to every scene Ivy’s in.

My one big criticism with Bitter Pill is that I wish Hay would’ve put as much effort into Chloe as he did with Ivy. We’re told that Chloe is the cool girl at high school you were always afraid to talk to. Yet she talked pretty much just like Ivy, except with a little more attitude.

We discussed dialogue just this Thursday and Friday and one of the things that came up was utilizing dialogue-friendly characters. Chloe could’ve been a dialogue superstar. You get to play with a 15 year-old girl with no filter in a black comedy? You had license to go nuts with her. Yet her dialogue was restrained.

Anyway, not a huge deal. The script was still good. Just needs another couple of drafts to meet its full potential.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

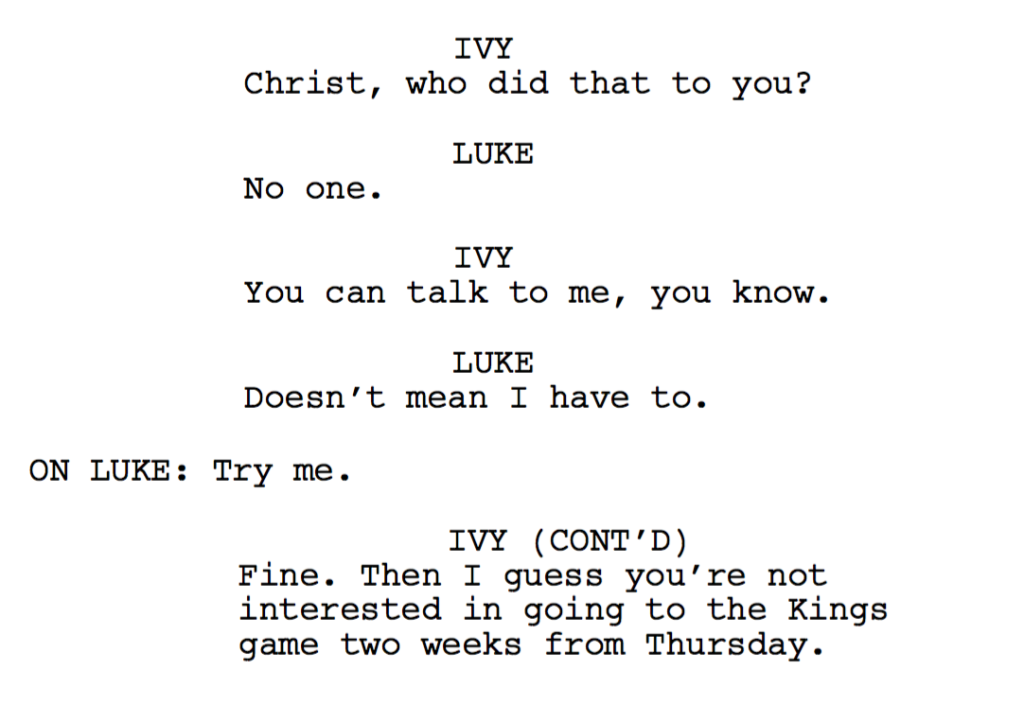

What I learned: This is a fun little dialogue trick. As you know, sometimes the best response to a line of dialogue is nothing. But you still want to convey a reaction – a specific feeling in the air from the recepient of the previous line of dialogue. In these cases, instead of writing the full reaction in an action line, which never quite flows the way you want dialogue to, write their name off to the side, a colon, and their feeling. Hay shows you how to do it here.