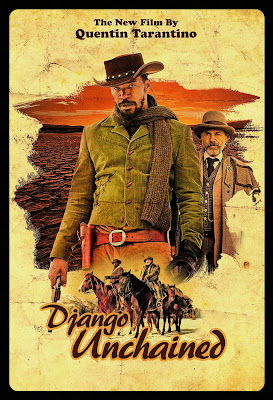

Genre: Tarantino

Premise: (from IMDB) With the help of his mentor, a slave-turned-bounty hunter sets out to rescue his wife from a brutal Mississippi plantation owner.

About: This is the next Quentin Tarantino film, coming out Dec. 25. Django Unchained stars Jaime Foxx as Django, Christoph Waltz as Dr. Schultz, Leonardo DiCaprio as Calvin Candie, and Samuel Jackson in the fearsome role of Candie’s 2nd hand man, Stephen. QT has wanted to do something with slavery for awhile, but not some big dramatic “issues” movie. He wanted to do more of a genre film. Hence, we got Django Unchained!

Writer: Quentin Tarantino

Details: 167 pages, April 26th, 2011 draft

These days, much of the time, I read scripts with a workman-like focus. That’s not to say I don’t enjoy reading. I love breaking down screenplays. But there’s always another script to read, another friend or consult or review to get to. Which means I have to stay focused, I have to get everything done.

Rarely do I read a script where I turn off the script analysis side of my brain and just enjoy the story. It happens two or three times a year. With Django, it actually went beyond that. Halfway through the script, I was so pulled in, I canceled everything and made a night of the second half of Django. I cooked dinner. I opened a nice bottle of wine. I pushed back deep into the crevice of my couch. I ate, drank and read.

Okay okay, so I didn’t actually cook anything. It was a lean cuisine meal. And I popped open a bottle of coke, not wine. I hate wine. But the point is, Django Unchained was that rare reading experience where the rest of the world disappeared and I just found myself transported into another universe.

And you know what? I’m not sure why the hell this thing worked so well. It was 168 pages. There was usually more description than was needed. Many scenes went on for ten pages or longer. BUT, Tarantino found a way to make it work. What that way is, I can only guess. Maybe it’s his voice? The way he tells stories makes all these no-nos become hell-yeahs. And that’s not to say he bucks all convention. There’s plenty of traditional storytelling going on here. It’s just presented in a way we’ve never quite seen before.

Django’s a slave who’s recently been purchased by a plantation owner. Part of a bigger group, the slaves are being transported to the new owner’s farm. There are a lot of nasty motherfuckers in this screenplay, guys way worse than the brothers pulling Django along this evening, but these men are still the kind that need a good bullet in the head to remind them of just how shitty they are.

Enter an upper-class German gentleman who appears out of the woods like a ghost. Dr. King Schultz is as smart as they come and as polite as you’ll ever see, and he’d like to ask these brothers which slave here goes by the name of “Django.” Predictably irritated, the brothers tell him to take a hike or take some lead. While respectful, Dr. Schultz doesn’t like to be told what he can and cannot do. So he smokes one of the brothers, disables the other, and makes Django a free man.

You see, Dr. Schultz is a bounty hunter. He gets paid lots of dough for the carcasses of wanted men. And it appears he’s looking for Django’s former owners, three rusty no-good brothers (there are lots of siblings in Django Unchained) who’ve changed their names and are hiding out on some plantation. Dr. Schultz will pay Django a nice sum if he can identify these men so he can kill them.

Now these men also happen to be the men who raped and branded his wife, Broomhilda. So yeah, Django knows who they are all right. He’ll help the strange German. Plus, with the money he earns, he can go off and search for his wife, who’s since been sold off to another owner. Django doesn’t know who or where, but Schultz tells him he’ll help him find her.

Away the two go, infiltrating the plantation where the brothers are hiding out, and Django gets some sweet revenge on his former slavers. The two are such a great team that Schultz recommends they extend their contract and start making some real money upgrading to the big names, the kind of names that need two people to take them down. Besides, he persuades Django, if they’re going to save Broomhilda, Django has to be in tip top shape.

So the two go off, hunting wanted men, and in their downtime, Schultz teaches Django how to read and shoot. Eventually, Django becomes the most educated badass cowboy around. And it’s a sight to see. And a sight people aren’t used to seeing. When townsfolk observe an educated free black man riding into their town on a horse, they think it must be some kind of joke. And at first, Django feels like a joke. But after awhile, he starts seeing himself the way Schultz does, as a man who deserves to be respected.

Once they’re ready, the two come up with a plan to save Broomhilda. Unfortunately, Broomhilda is being held by one of the nastiest plantation owners in all the state, a detestable villanous soul named Calvin Candie, and Calvin Candie won’t just see anybody. If you want his attention, you have to pony up. Which means Schultz and Django must pretend to be looking for a fighter in one of Calvin’s favorite hobbies – Mandingo fighting. Basically, these are slaves forced to fight other slaves for white men’s entertainment.

In their scam, Schultz will play the rich interested party, and Django will play the “Mandingo expert” he’s hired in order to find the best fighter. Calvin could give two shits about the two until Scultz says the magical words, “Twelve thousand dollars.” Now Calvin’s ready to talk, and he decides to take them back to his plantation where the talking acoustics are a little nicer, the amusement park-esque estate known as “Candyland.”

While at Candyland, the two covertly scope out Broomhilda’s whereabouts, except that Calvin’s number 2 guy, groundskeeper Stephen (who’s, surprisingly enough, Calvin’s slave), suspects something is amiss with these men, and starts to do some digging. It doesn’t take him long to figure out their intentions, intentions that have nothing to do with buying a Mandingo. He lets his boss know, and for the first time since we’ve met Django and Shultz, the tables have turned. They’re not in control of the situation anymore. Once that happens, our dynamic duo is in major trouble. And it’s looking unlikely that they’ll find a way out of it.

Let me begin by saying that a big reason this script is so awesome is because of the GOALS and the STAKES. There’s always a goal pushing the story forward, which is extremely important in any screenplay but especially a 168 page screenplay. If your characters don’t have something important they’re going after, a solid GOAL, then your story’s going to wander around aimlessly until it stumbles onto a highway and gets plastered by a semi. A gas tanker semi. A gas tanker semi that explodes and starts a forest fire.

The first goal is Schultz’s goal of needing to find these brothers. Once that goal’s taken care of, the true goal that’s driving the story takes center stage – Django needs to find and save his wife. But, you’ll notice that even when we’re not focused directly on that, we have little goals we’re focusing on. It may be to kill one of the many wanted men they’re hunting. It may be to learn to read or fight or handle a gun, so that Django can be equipped for his final showdown. QT makes sure that we’re always driving towards something here, and he does it with goals. Goals that have stakes attached to them. How can the stakes be any higher than your wife’s safety and freedom?

But that’s not the only reason. Outside of Mike Judge, I don’t know any writer who can make his characters come alive on the page better than Tarantino. He just has this knack for developing unique memorable people. I can go through 5-6 scripts in a row and not read one memorable character. This script has like two dozen of them. It’s amazing. Sometimes it’s because he subverts expectations – Dr. Schultz is a German in an unfamiliar land who’s as dangerous as fuck yet always the most polite man in the room. Sometimes it’s through irony – A slave bounty hunter hunting the very white people who enslaved him. And sometimes it’s just a name – Calvin Candie. I mean how perfect a name is that? How are you going to forget that character?

I tell writers NEVER to overpopulate their screenplays with large character counts because we’ll forget half the characters and never know what’s going on. But when you can make each character this memorable? This unique? You can write however many damn characters you please.

And the dialogue here. I can’t even tell you why it’s so awesome because I don’t know. There are certain elements of dialogue you can’t teach and QT is one of the lucky bastards who possesses that unteachable quality. But I will tell you this, and it’s something I’ve become more and more aware of in subsequent Tarantino movie viewings. He depends on a particular tool to make his scenes awesome, and it’s the main reason why he can write such long scenes and get away with it.

Basically, Tarantino hints that something bad/crazy/unpredictable is going to happen at the end of the scene, and then he takes his time building up to that moment. Because we know that explosion is coming at the end, we’re willing to sit around for six, eight, ten pages until we get there. The anticipation eats at us, so we’re biting our nails, eager to see what’s going to happen. In these cases, the slowness of the scene actually works for the story because it deprives us of what we want most, that climax.

For example, there’s a scene in the second act where the young man who’s bought Broomhilda and since fallen in love with her, takes her out for a night on the town. He unfortunately walks into one of Calvin Candie’s establishments and before you know it, Candie himself has invited him over to his table to play poker with the big boys. Broomhilda knows something’s not right, but the poor soul is too flattered to listen to her. This scene goes on and on and we see that Candie is becoming more and more sinister, and we just know this isn’t going to end well. We know something terrible is going to happen. So of course, we’re on the edge of our seats dying to see in what terrible way it will end.

Tarantino also did this, most famously, in the opening “Milk Scene” of Inglorious Basterds. A German Commander shows up at a farm house looking for fugitive jews, and we just know this isn’t going to end well. That’s why the German commander can ask for something as unexciting as a glass of milk. That’s why he can talk about mundane things for minutes on end. Because we know this isn’t going to end well, yet we’re dying to see how it does end. Go through Django Unchained again and you’ll see that there are LOTS of these scenes, and one of the biggest tricks Tarantino has in his toolbox. He keeps going back to it, and it works every time.

But what I think really separates Tarantino from everyone else is that you never quite know where he’s going to go. You can predict most movies out there down to the minute. But with QT, you can’t. And it’s because he already knows where you think he’s going to go, so he purposely goes somewhere else. Take the opening scene, where we see a polite white man being kind and cordial to a slave. Not prepared for that. Or when we see that Calvin Candie takes his orders from a black man, his slave, Stephen. Or how when Broomhilda is first purchased, she’s actually purchased by a shy young white man who quickly falls in love with her and treats her kindly. I was always trying to predict where Tarantino would go next, and I was usually wrong. And even better, the choice he ended up going with always ended up in a better scene.

My complaints are minimal. There was only one area of the script that felt lazy. (spoiler) Late in the third act, Django’s life is spared because, apparently, he’ll experience a much worse death “in the mines.” This allows him to be transferred off the plantation, which of course allows him to trick his transporters and go back to save Broomhilda. Come on. No way the Candie family doesn’t torture and kill him right there. No way they let him go off to the mines. So I was disappointed by that because it felt like a cheap way to give Django his big climax. With that said, the big climax was phenomenal. Average Joe Writer would have had Django go in there Die Hard style. QT took a slower more practical approach, and created a much better finale because of it.

So you know what? I can’t believe I’m doing this since I haven’t done it in two years before a month ago, but I’m giving another GENIUS rating. This script is freaking amazing. It really is. I don’t know if the Academy knows what to do with a movie like this, but if we’re talking writing alone, this script should win the Oscar. And, heck, it should win for best film too.

What I learned: Always look for ironic moments in your screenplay. Audiences LOVE irony. Django, a slave, must play the role of a slave driver near the end of the film. He must treat other slaves like they’re dirt. He must talk to them like they’re dirt. It’s tough to watch but also fascinating, since he himself was, of course, a slave a short time ago.

.jpg)