In a fascinating display of courage, Mel Gibson brings us a hero who is the exact opposite of American Sniper’s Chris Kyle.

Genre: Biopic

Premise: The story of the first conscientious objector (a World War 2 soldier who refused to pick up a gun) to win the Medal of Honor, America’s highest award for courage under fire.

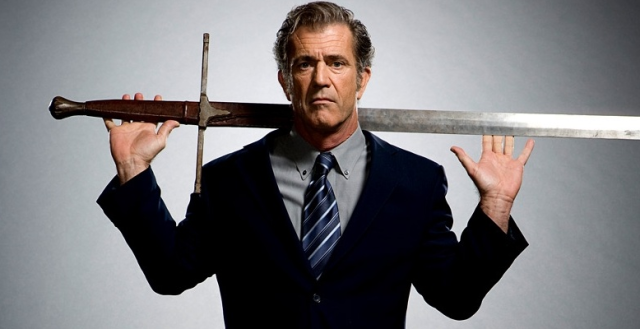

About: It’s like Braveheart week here at Scriptshadow! Mel Gibson the director is finally back and that’s a great thing. Gibson is one of the best living directors out there. He just doesn’t make a lot of movies. But Hacksaw Ridge will be his next. What’s extra cool about this draft of Hacksaw is that Braveheart writer Randall Wallace revised it! The original writer is 62 year old Robert Schenkkan, who’s probably best known for writing the 2002 film, The Quiet American with Michael Caine, although he definitely has some WW2 experience, writing for “The Pacific” mini-series a few years back. Vince Vaughn, Andrew Garfield, and Sam Worthington will star.

Writers: Robert Schenkkan (revisions by Randall Wallace)

Details: Marc 12, 2013 draft

You know, it took me awhile to figure out why American Sniper became such a huge hit. But I finally got it. The majority of modern-day war films are liberally slanted. The overwhelming message is that war is bad and it destroys the soldiers who engage in it.

That’s precisely why those movies never made money. Conservatives didn’t want to see them because they depicted war badly. And liberals didn’t want to see them because liberals aren’t interested in war.

American Sniper may not have been a “rah-rah” war film. But it definitely celebrated its subject, Chris Kyle, for killing a hell of a lot of people. Finally, conservatives had a reason to go to the theater. They were no longer being preached to that “war was bad.” And you’re never going to get more liberals to a theater than when a war film is being celebrated by conservatives.

So it seems odd amongst Eastwood and writer Jason Hall’s formula for success that Mel Gibson would bring to market the anti-Chris Kyle. We’re going right back to the liberal slant here. Desmond Doss is a man who joins the army at the beginning of World War 2 and refuses to pick up a gun.

These people are known as “conscientious objectors” and they’re actually supported by the United States government. There’d be a bit of hypocrisy if our country fought for the freedom to have our own beliefs and yet forced counter beliefs on the soldiers we sent out to obtain that freedom. The thing is, nobody actually REFUSED to touch a gun as a soldier. Nobody, that is, except for Desmond Doss.

Hacksaw Ridge spends its first act setting up Desmond’s home life back in the Virginia Mountains, with his depressed father, followed by him falling in love. The first part of the second act has Desmond training to be a soldier. It’s in this section that we see just how anti-gun Desmond is, and how he avoids violence altogether. In fact, when another soldier beats his ass, he just curls up in a ball and takes it.

Desmond’s plan, if you can call it that, is to be a medic. In his view, medics don’t need guns. Because the truth is, Desmond WANTS to be a soldier. He wants to help his country win the war. He just doesn’t want to have to kill anybody to do it.

FINALLY, after we pass the midway point, we get to the meat of the story – Hacksaw Ridge. This is a specific ridge on Okinawa Island that needs to be secured to take the island. The island is a key waypoint in the war. If they take the island, they can use it as a major launching point to attack Japan. In short, take Hacksaw Ridge, win the war (stakes!!!).

This sets up the final act, which is the star of the script by a billion. When Desmond’s company is brutally attacked by the Japanese and the rest of the company runs to safety, Desmond stays back and retrieves every single fallen soldier. All without ever firing a gun! It is for this display that he wins the Medal of Honor.

From a screenwriting perspective, Hacksaw Ridge is a unique challenge. In movies, we like main characters who DO THINGS. Who are ACTIVE. Who are BLAZING THEIR OWN TRAILS. To center a movie around someone whose key action is a negative one (RESISTING) is a tough sell.

And to be honest, that kept me from liking Desmond Doss. Nobody likes the weirdo who refuses to fall in line because of his weird beliefs. I mean seriously, remember the kids whose parents wouldn’t let them dress up for Halloween because of some weird belief?? We weren’t hanging out at those kids houses after school. And it’s also hard to root for someone who doesn’t stick up for himself. When someone tries to fight Desmond, he curls up into a ball and waits for the beating to end???

I actually found myself siding with Desmond’s superiors most of the time. When they said to him, “Just grab a fucking gun,” I was like, “Just do it!” It’s not like he had to fire it. Just hold it for appearances and don’t ever shoot it. There seemed to be ways around this issue that he wouldn’t entertain simply out of stubbornness.

But I’ll tell you what saved this script. The ending. The ending here is fucking awesome. It IS the movie. And you know afterwards why this is called Hacksaw Ridge, a seemingly insignificant title for 75% of the movie.

The ending is great because Desmond Doss finally becomes a hero. He finally DOES something. He’s finally ACTIVE. He’s not just being an annoying pain in the ass refusing to pick up a gun for trivial reasons. He’s the ONE soldier who stays back when his company is gunned down while all the other soldiers – the same ones who were calling him out for his weirdness – ran back to the safety of their camp. And he saves every single soldier who’s still alive despite an entire Japanese company dug in trying to gun him down. It’s a fucking fantastic scene.

In particular, there’s this moment where Desmond has machine gunners off to his left and a sniper off to his right while trying to get to a soldier who’s right in the crosshairs of that line of fire, and he somehow pulls it off. It’s one of the best scenes I’ve read all year.

And it goes to show, if you’re going to write 90 minutes of average and 20 minutes of great, MAKE SURE THAT GREAT IS AT THE END. Because I left this script ready to see Hacksaw Ridge. And I would not have felt that way if this had been structured like Saving Private Ryan, where the movie’s best scene was placed at the beginning.

Hacksaw Ridge shows the power of a true hero. We’re not so sure about this Desmond guy for ¾ of the screenplay, but the second he becomes the bravest man on the battlefield, we love him.

And I’ll finish with a suggestion for Mel, since I know he cares so much about what I have to say. This whole movie is dedicated to this idea that Desmond refuses to pick up a gun. So there should be one scene in the film where the SPECIFIC ACT OF HIM NOT HAVING A GUN saves him. Where, if he had a gun, he would’ve been killed. I don’t know how you do that. But I firmly believe that whatever your hero’s perceived “weakness” is, at a key point in the story, that weakness should become a strength.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Here’s a thing that you should never do in a script. Never tell us your character is “unique” or “different.” We should be able to draw that conclusion on our own. That means coming up with actions or situations or choices that SHOW us your character is unique or different. Early on in Hacksaw Ridge, after Desmond stares at a painting for an inordinately long time, the writers write something to the effect of, “And that’s when we realize Desmond Doss is very different from other human beings.” No. No. Don’t ever do that. Convey weirdness through action, through choice. Go watch Nightcrawler to see how this is done right. The early scene where Louis Bloom makes an awkward proposal to be employed by a man sells you on his weirdness. Gilroy never had to write, “Man, this Edward Bloom is really weird. We see that weirdness in everything he does.” That’s a big no-no and usually indicates that you subconsciously know your hero isn’t as weird as you want him to be. So you literally have to TELL the audience to get it across.

What I learned 2: When a potentially melodramatic scene approaches, consider going with the OPPOSITE line of dialogue than what your instincts are. For example, there’s a scene where Desmond’s father is telling him that he doesn’t want him to go to war. But Desmond has already committed to it. An amateur writer would’ve had the father say something to the effect of, “I love you more than anything. Don’t do this.” Instead, Schenkkan and Wallace have the father say: “You’re a terrible son. I hope they kill ya,” and walk away.