Genre: Drama

Premise: A steamboat captain is recruited by a British ivory company stationed in Northern Africa to find one of its men who’s lost in the jungle.

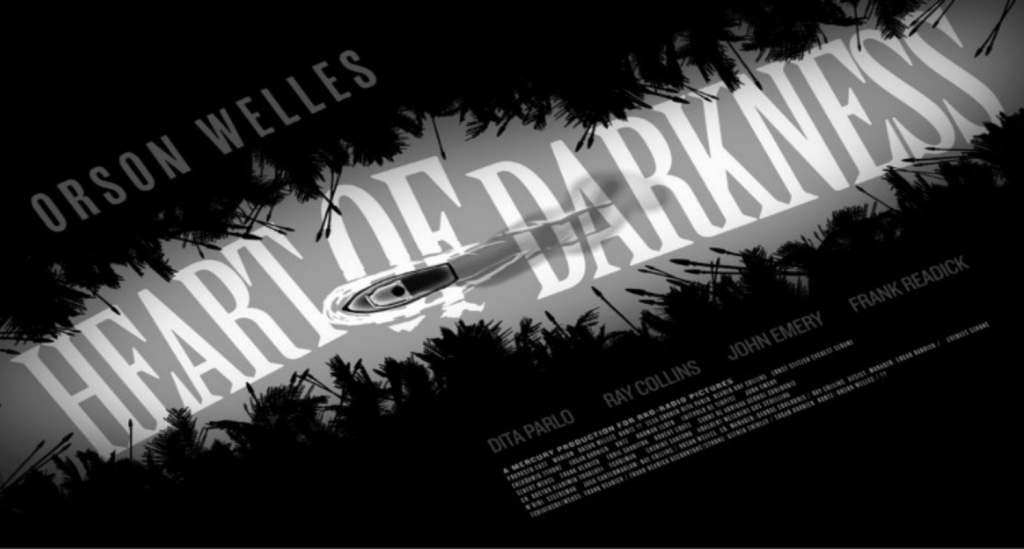

About: Best known for tricking radio listeners into thinking the earth was under attack by aliens from Mars, and for creating the “best film ever made” in Citizen Kane, Orson Welles is also known as the poster child for lost opportunity. His choice to make a movie about one of the most famous newspaper magnates ever to live (Randolph Hearst) during a time when newspapers were so powerful, they shaped our very reality, Hearst, who knew every bigwig in Hollywood, demanded Welles not be able to make any more movies. And that’s pretty much what happened, with Welles only trickling out a handful of films during his career. Heart of Darkness was a casualty of this blackballing, and a movie Hearst desperately wanted to make.

Writer: Orson Welles (based on the novel by Joseph Conrad)

Details: 185 pages

In one of the most famous movies never made, Orson Welles had plans to be the first filmmaker ever to shoot an entire movie from the main character’s POV. While this is merely an artistic choice today, back then, with the weight of the cameras and how difficult it was to set up even a basic still shot, the process for filming a 2 and a half hour POV movie would’ve been an almost impossible undertaking, which is at least partly why this movie never got made.

It should be no surprise that Welles wanted to tell this story. The dude is dark. He routinely spat out quotes like this one during his life: “We’re born alone, we live alone, we die alone. Only through our love and friendship can we create the illusion for the moment that we’re not alone.” Holy barnacles, batman. Someone please check the going rate on nooses on Amazon.

Heart of Darkness starts out, rather amusingly, with Orson Welles staring at us while we’re lodged inside a bird cage. He then tells us, the audience, that in this film, we’ll be seeing the movie through the main character’s eyes. He then shoots us, killing the bird version of ourselves, to show us just how powerful this device will be.

Then, even more amusingly, as if he didn’t think that would be enough to convey just how outrageous this first person approach will be, he places us in the shoes of a prisoner, then walks us to an electric chair and executes us. If we hadn’t understood the device that would be guiding us through the movie before, we did now.

That leads us to Marlow, our main character, who also happens to be us. We’ll be experiencing the movie through Marlow’s eyes. Marlow is an American steamboat captain who’s been tasked to go to Northern Africa to find a missing member of “The Company,” that being an ivory trading company based out of Britain.

The missing person is the mysterious Kurtz, who’s so elusive we’re not even sure what he does. Kurtz is located deep in the jungle, up one of thousands of river tributaries, at a remote station where he’s pulling in more ivory than the rest of the company combined. But Kurtz hasn’t written the company in awhile, and people are getting worried.

So Marlow, or “us,” team up with Kurtz’s beautiful and flirty fiancé, Elsa, to find this man that nobody can stop talking about. The further inward they go, the clearer it is that this place is hell on earth, a breeding ground for disease and death. The few who somehow escape these scenarios, often end up crazy. That, they fear, is what’s happened to Kurtz, and if we don’t find him soon, what may happen to us.

Welles wrote this script when he was 25 years old, and it feels like it. Those early 20s scripts are always the most ambitious as you want to change the world and redefine the medium. You’ll throw in any and every weirdness you can just to stand out. Who cares if it serves the story. As long as it gets people talking!!

With that said, if there’s anyone who’s capable of getting away with that, it’s Orson Welles. Every choice he made in Citizen Kane, someone told him he couldn’t do it and he did it regardless. Greatness is never born out of someone saying, “I want to do this exactly the same way everyone else has done it.” So there’s something to be said for Welles’ gung-ho attitude here. And, in his defense, the subject matter warrants taking chances.

But the first person perspective, while cool in theory, presents several storytelling problems. And the mistakes made from scripts like this one, as well as its cohorts that eventually made it to the screen, only to quickly be forgotten, are likely what inspired the first generation of screenwriting professors to say, “Maybe doing it this way doesn’t work.”

What’s one of the first things they teach you in Screenwriting School? The main character needs to be active. Why does the main character need to be active? Because active characters drive stories and because audiences like people who DO things as opposed to people who REACT to things.

And that’s pretty much all Marlow does, is react. In fact, the entire movie consists of him watching OTHER PEOPLE do things. True, he is the captain, so he is taking our characters to Kurtz. But there’s never a situation where Marlow is like, “We need to go that way!” And he runs to the steamboat room and starts pouring on more coal before running out and pulling a rare Fast And Furious’esque figure-8 steamboat move to barely make it into the Katonka River.

It’s more like, someone will come up to him and say, “Hey, how you feeling?” And Marlow will say, “All right. I wonder what the weather is like back home.” There are a lot of interactions like that, giving us a character dominated by a whole lot of inactivity.

It’s not a total bust though. Heart of Darkness conveys just how popular build-up can be. If you build something up enough, the audience WILL stick around until that thing arrives. I don’t think I’ve ever heard one thing (the name “Kurtz”) mentioned so many damn times in a single script.

Every other word out of someone’s freaking mouth was “Kurtz,” to the point where even though I was bored to tears because nothing else was freaking going on, I wanted to find this Kurtz fellow! I mean, with so many people talking about him, he had to be worth the wait, right?

What I also found interesting was that despite this novel being written over 100 years ago, that even back THEN they were still using love triangles. I say that because you think of a love triangle as a cheap literary device used to stir up some artificial conflict. But the magnetic and flirtatious Elsa working her magic on Marlow while her fiance, Kurtz, draws closer every minute, was of the more dramatically compelling storylines in the script!

The weird thing, though, is that the very thing I found gimmicky at first – Welles’s cheesy masturbatory opening sequences – was exactly what I craved more of as we made it past the century page mark. The script gets so bogged down in its dark subject matter and relentless attention to camera detail (seriously, the word “CAMERA” was easily used over 600 times in this script), that there wasn’t any fun left. Add on a protagonist who just watches everyone else do things without doing anything himself and you can see why something like this would get boring quickly.

The only thing to keep our interest was that damn Kurtz. But because, at a certain point, that’s all the story had to offer, even I had to dive into the water and swim back to shore. This would’ve been an interesting experiment had it ever been produced, but very likely a failed one. That’s exactly what the studio head said to Welles at the time. And do you know what Welles came back with? “No problem. I have another idea. It’s called Citizen Kane.”

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You are not as clever as you think you are. When you think that you’re rewriting the cinematic language by talking directly to the reader or going first person POV for an entire script? Know that there was a script written as far back as SEVENTY SEVEN YEARS AGO that was doing the same thing. When it comes to screenwriting, choose the most compelling story you can write over writing something gimmicky with tons of bells and whistles. If Orson Welles couldn’t pull it off, you probably can’t either.