Lincoln’s screenplay reverses the adage of “show don’t tell,” leaving us a show that doesn’t tell us much at all.

Genre: Historical

Premise: (from IMDB) As the Civil War continues to rage, America’s president struggles with continuing carnage on the battlefield and as he fights with many inside his own cabinet on the decision to emancipate the slaves.

About: Lincoln was written by Tony Kushner, whose play “Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes” earned him a Pulitzer Prize. His last feature credit before this was 2005’s “Munich.”

Writer: Tony Kushner (based in part on a book by Doris Kearns Goodwin)

Details: Dec 20th, 2011 draft (shooting script)

I don’t want to offend any Lincoln lovers here. I assume this movie is kind of like their baby. There’s none of that ridiculous goosed-up Hollywood bullshit with splosions or vampires or anything else that might be mistaken for “entertainment.” Entertainment is not the name of the game when Spielberg does serious. One need only watch the trailer to see that. Period Piece men in wigs talking in rooms about things like Amendments and Bills for two hours. THAT’S what you’re getting here. Again, if I’m a Lincoln-era history buff, this is nirvana. But if I’m a moviegoer? This sounds like hell. I shall now put on my script-pray boots and hope that I’m wrong.

It’s January 1865. Two months have passed since Lincoln’s re-election. The American Civil War is in its 4th year. This is actually one of the few things the script did well – let us know where we were in history. This is critical when you’re writing a period piece because the mood of the world (or a nation) in one era can be completely different from the mood in another. The overall tone is going to be different if we’re following, say, Rome at its peak, than if we we’re following Europe after the Black Plague. So it’s a smart move to start your story by putting everything into context for us.

Lincoln starts with a scene that’s pretty indicative of the entire screenplay. CHARACTERS TALKING. Two black soldiers are chatting with Lincoln about the war. They’re noting how white soldiers have better guns and provisions than them. Lincoln looks sort of troubled by this. So we use our crucial opening scene to establish that Lincoln wants to help black soldiers. Wow, profound stuff here. Talk about beginning your movie with a bang.

Lincoln then heads back to chat with his wife (more characters talking in rooms) who expresses disappointment that he’s so set on passing the 13th Amendment. Now I may have this wrong (again, you have to realize how dense this script was) but the central conflict of the story seems to be that Lincoln has already freed the slaves during the war. However, he’s afraid that once the war is over, the democrats are going to say he abused his war powers and therefore reverse the ruling. For this reason, Lincoln wants to make it official, and he feels he’ll have an easier time if he can get the amendment passed now as opposed to after the war.

As it stands, all the republicans in the house are going to vote for the Amendment. But with the democrats outweighing the republicans in the House, Lincoln’s still going to need over a dozen democrat votes to pass the bill. Getting democrats to vote for the 13th isn’t going to be easy, with most of them fearful of the repercussions of going against their party. So Lincoln starts telling his Cabinet to offer the democrats jobs to convert them. I’m not kidding you. This is the rollicking story we get. Men in rooms trying to convince other men in rooms to vote their way by bribing them with jobs.

There are some semi-relevant things going on in the war (which we never see – why would we? That might be interesting!) but none of it was very clear or compelling. Or maybe it was clear and I just didn’t find it compelling. I’m trying to give the script the benefit of the doubt and hope that I missed something because I’d hate to think that this is all that’s going on here – 70 scenes of lobbying. The script even ends with a huge 20 minute sequence where we watch almost every single person in the house say “yay” or “nay” to the bill. Good lord, someone shoot me now.

Look, I’m not downplaying the importance of Lincoln’s achievements. But there are so many ways to dramatize events like these so that they’re actually entertaining and this script didn’t do any of them. Its slow redundant action-less narrative felt like it was daring you to hate it, as if by doing so, you weren’t appreciating one of the most important moments in American history. I’m not saying it had to be Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. I’m saying give us SOMETHING compelling to watch. A central battle that would have immense implications on the bill. Anything other than men talking. And talking. And talking!

There’s an old screenwriting saying that goes, “Show, don’t tell,” and everything about this script did the opposite. It’s ALL telling and NO showing. Every scene is important men wearing silly wigs having boring conversations in small rooms. Everyone’s telling everyone else what to do and why to do it and what they feel. There’s very little subtext here. You have the “good” guys on this side and the “bad” guys on that side and that’s that. And the monologues. Oh God, the monologues. There were a million of them. I had monologue-fatique by page 60.

Lincoln even relies heavily on the dreaded “dual-line dialogue.” This is a signature of a screenwriter who’s a) just starting or b) doesn’t write many screenplays. Because the longer a screenwriter’s around, the more he/she realizes how incredibly unpleasant dual-line dialogue is to read. And that goes double for a script like this, which is already struggling to keep our attention. You’re telling me that I not only have to read ONE endless chunk of dense exposition theme-laden dialogue, but TWO? And I don’t get any further down the page by doing so??

The funny thing is, the script does follow the GSU model pretty closely. You have the goal (get the 13th Amendment passed), the stakes (if you fail, slavery might be reinstated), and urgency (they had to do it by the end of the war, which was coming up soon). But what was different about this goal than say, the goal in Zero Dark 30, was that THE REASON for killing Bin Laden was so damn clear. Here, the goal’s a little vague. Lincoln has already freed the slaves. Now he thinks MAYBE that MIGHT be overturned when the war is over? But he’s not sure? So he’s going to double down? It just all seemed a bit uncertain to me and if the goal isn’t imperative, if it isn’t 100% necessary, the sakes suffer, and so does the audience’s interest. And then of course there was the issue of 70 straight scenes with characters in rooms talking. That didn’t do Lincoln any favors.

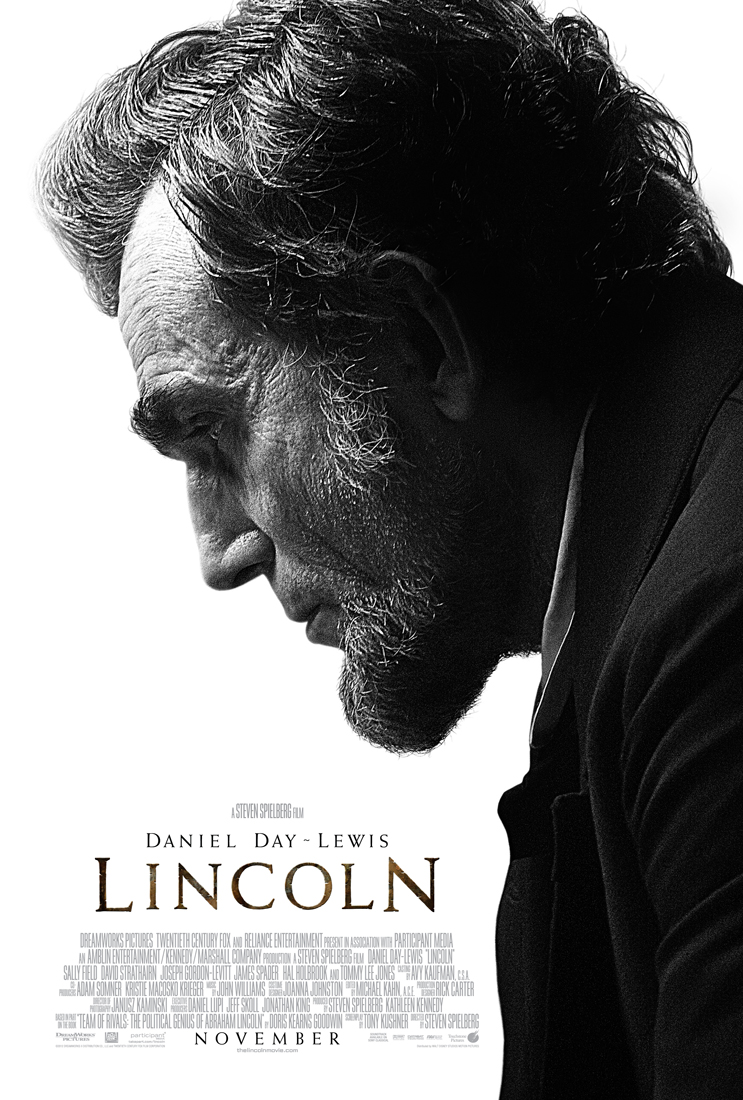

If there’s one good thing to say here it’s that Kusher’s script got Daniel Day-Lewis on board. I think writers forget how important this is. Getting the star you want (or the actor who’s going to make your project a go) is one of the hardest things to do in show-business and that’s because the best actors have the best material, which means the competition is fierce. That’s actually what happened here. Spielberg wrote a draft of Lincoln that Day-Lewis turned down! So it’s a major achievement to write the draft that the big actor says yes to. But whatever Day-Lewis saw in this part didn’t transfer to the rest of the story. Again, history geeks are going to have orgasms over this. But people who like watching good movies are not. Tony Kushner seems to be an incredibly accomplished and talented man. But I don’t think screenwriting is the best venue for his talents.

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I Learned: Monologues are a toughie. Story-wise, they’re script killers, because they often slow the script down to a crawl. However, actors LOVE monologues. And that has to be factored in. So here’s how I would play it if I were you. If you’re writing to get your foot in the door, don’t have more than two monologues in your script. Producers want fast scripts and two monologues is usually the maximum you can get away with (this number, however, will vary depending on the particular story and the writer’s ability to write dialogue. Tarantino or Woody Allen, for example, can get a way with a lot more monologues than, say, David Guggenheim). Now if you’re getting your script to a big ACTOR, you can add another monologue or two for that character. This actually happens a lot. When a producer/writer team are about to send a script to a big actor, they do a pass beefing up the part to make it more interesting. I have no idea why Daniel Day-Lewis turned down Spielberg’s draft but accepted Kushner’s, but I have a sneaking suspicion all those monologues played a part.