Genre: Biopic

Premise: In the 80s, a rogue pilot becomes Ground Zero for the majority of the cocaine being smuggled into the US. The crazy thing? He’s being funded by the United States government.

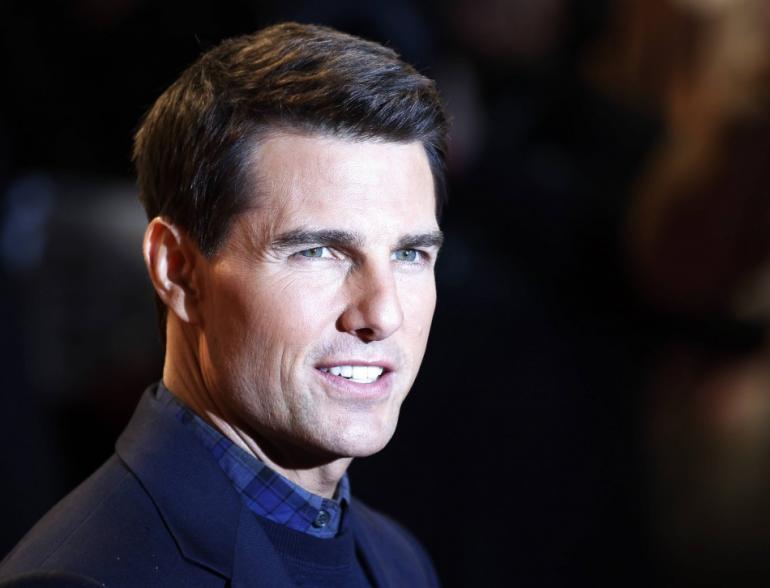

About: This was a huge “spec” package early last year. Sold for 7 figures with Ron Howard attached to direct. It’s since nabbed Tom Cruise as the lead to play Barry Seale and Doug Liman (who teamed with Cruise on Edge of Tomorrow) to take over directing duties. The script also finished in the top 10 of the most recent Black List. I remember reading Spinelli’s breakthrough spec five years ago – a clever idea about a man who kidnapped criminals and auctioned them off to rival crime bosses. It didn’t put him on the top of any studio’s list, but it got the town’s attention. He kept writing and, five years later, nabbed one of the top 3 spec sales of the year. It just goes to show that you’re playing the long game here. Break through with a cool spec, don’t celebrate, put your nose back to the grindstone, keep writing, keep generating material, get more and more people familiar with your work. Then one day, that opportunity presents itself for a huge payday and the ultimate goal of being a produced writer.

Writer: Gary Spinelli.

Details: 128 pages – 10/26/13 draft

It’s a new world. A biopic world. After American Sniper, scripts like Mena, Jobs, and that McDonald’s movie are top priority for studios sick of working on the next actors-in-tights SFX fiasco (I mean seriously – is anyone really that excited to work on Wonder Woman?). Now I could go on my rant about why I’m not a huge fan of biopics, but the first half of Mena makes my argument for me.

There isn’t a single dramatized scene in the first 67 pages of this screenplay. The entire first half of the script is voice over and exposition. This doesn’t seem to bother some people and I can’t for the life of me figure out why. It’s nice to learn fun tidbits about how we stole weapons from Palestine, then sold them to secretly win wars in South America. But unless you give me a few scenes with some actual suspense mixed in, I’m going to have a hard time staying awake.

But hey, I was singing the same uninspired tune after reading American Sniper. And look how that turned out. This could be a very good omen for Ron Howard and Co.

Mena follows our adrenaline junkie hero, TWA pilot Barry Seale, through the 1980s, when he realizes he wants something more out of life. Being a commercial pilot pays well. But “light rain” on the runway is hardly enough excitement to get Barry up in the morning.

So when Barry gets an offer from the CIA to fly small planes through South America to track revolutionary movements there, he takes it. Being opportunistic, Barry then uses the contacts he makes in South America to smuggle cocaine back into the U.S.

Thinking he’s sly, Barry is shocked to find out that the CIA knew what he was doing all along. In fact, they orchestrated it! By having someone in tight with the cartels of South America, it allows them to influence the factions of government that run things down there. They also start using the money Barry makes from the drug running to purchase stolen weapons from the Palestinian war and sell those weapons to U.S. friendly forces down in South America.

Confused? I sure as hell was.

Anyway, a local cop in the tiny town Barry lives in starts to suspect that Barry is a shady character (could it be the giant mansion he’s built in the cash-strapped town?) and begins looking into his suspicious activities. To make matters even more complicated, the president at the time, Ronald Reagan, declares a war on drugs, seeking to destroy operations like Barry’s, despite the fact that he’s unofficially funding him!

The next thing Barry knows, the FBI is moving into town. The attorney general wants to know what’s up. And Barry’s supposedly untouchable operation is at risk of imploding, bringing down himself, the South American drug trade, and the CIA. You can bet your ass though, that when those organizations are threatened, the last person they’re going to be thinking of protecting is Barry Seale.

Clearly, this was written with the hopes of getting Scorsese to direct. It’s got his signature “Mythology Breakdown” opening, where he over-examines the intricacies of the subject matter via copious amounts of voice over. Instead of Scorsese, though, we get Doug Liman. Which, while no Scorsese, is still an upgrade over Ron Howard. Ron Howard trying to pull off a Scorsese film is a little like Nicholas Sparks trying to write Fight Club.

Here’s my big issue with Mena, regardless of who’s making it. Barry’s external life is an interesting one. He’s robbing the very government he’s working for. He’s using his drug connections to make himself rich. He’s delivering weapons that are shaping the future of South America.

But go ahead and read back those accomplishments. They’re all EXTERNAL. It’s not Barry who’s interesting. It’s the situations he finds himself in that are interesting. Barry himself is a pretty basic dude. There’s no real conflict within him. He’s not battling any demons. His relationship with his family is practically an afterthought (at least in this draft). So what is Barry dealing with on an internal level?

At least with Chris Kyle in American Sniper, you could feel a battle raging inside of our protagonist. He’s been made a hero for killing people –in some cases children. And he struggles to come to terms with that. I guess I wanted more of a character study in Mena and not just two hours of “look at all this crazy shit that’s happened to me.” Especially because we’re not so much being SHOWN this crazy shit as we’re given an audio play-by-play of it.

Earlier I was talking about the lack of a dramatized scene until page 67. What did I mean by that? Well, the first 67 pages of Mena consist of Barry laying out the bullet points of how he smuggled drugs and ran weapons back and forth between the Americas. There wasn’t a single scene between characters that consisted of an unknown outcome.

Finally, on page 67, Barry is tasked with having to kill his brother-in-law and partner, who’s been captured by the police. After getting him out on bail, Barry plans to take his partner out to the desert and kill him. FINALLY! A SCENE WITH SOME FUCKING SUSPENSE! It was the first time I actually leaned in and was excited to see what happened next. For once, there wasn’t a Wikipedia voice over yapping away at me.

And that’s how I like my stories told. I like when writers set up uncertain situations that hook us into wanting to read more. I get that we have to set SOME story up first but, man, 67 pages is an awful long time to set up story.

There’s definitely something to Barry Seale. There are too many wacky components to his life to call this an ill-informed project. But we must remember that while the external stuff is always fun, it’s not what’s going to emotionally hook an audience. If you’re writing a biopic, you’re saying that first, and foremost, this is a character study. So give us a study of the character. Not just the shit he gets into.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A great way to write a suspenseful (dramatized) scene is to follow this formula:

a) Create a problem that results in a difficult choice for your main character.

b) Make the stakes of that problem as high as you can.

c) Have the outcome of this issue completely unknown.

d) Draw the scene out as long as you can.

This is why that scene on page 67 brought my full attention to the script for the first time.

a) Barry knows the only way to keep his step-brother quiet is to kill him.

b) If Barry doesn’t kill him, the CIA and the Columbians will come after Barry.

c) We sense Barry is going to kill his step-brother but we don’t know for sure.

d) This all plays out over a long car ride from the jail to the desert.