Genre: Crime Drama

Premise: A team of corrupt cops come up with a unique plan for a heist that involves eliminating one of their own.

About: Writer Matt Cook has been pushing his way up the seemingly endless ladder to a produced credit for awhile now. He first hit Hollywood’s radar back in 2010 with his Black List script, By Way of Helena. That’s what a lot of aspiring writers forget. The system doesn’t allow screenwriters to just barge in and start snagging movie credits. It makes them work for it, prove that they have staying power first. Then, and only then, are they given a shot at the big time. Well, Matt’s certainly making his debut count. Triple Nine will star Aaron Paul, Kate Winslet, Norman Reedus (Walking Dead), Woody Harrelson, Anthony Mackie, Casey Affleck, Chiwetel Ejiofor, and future Miss Wonder Woman, Gal Gadot. John Hillcoat, the director, is best known for his gritty apocalyptic flick, The Road. The irony of all this? Matt’s script was originally written back in 2010, the same year he broke out. That’s the draft of the script I’ll be reviewing. But I’m sure they’ve since gone through plenty of rewrites.

Writer: Matt Cook

Details: 126 pages (June 22, 2010)

Pinkman’s being smart by staying within his genre wheelhouse.

Pinkman’s being smart by staying within his genre wheelhouse.

We love our movies, don’t we? We love them so much we strive to bring them back to life with every script we write. Why else would JJ Abrams make Super 8 (E.T.)? Or Ben Affleck make The Town (Heat). The problem with re-writing your favorite films is that they don’t have their own identity.

One of the biggest tests for an artist, and what truly separates the trendsetters from the trendfollowers, is to let the movies of your past influence and inspire you, but never overcome you. When you find that magic balance, you become a Wes Anderson or a Quentin Tarantino, someone who was influenced by something, but not dominated by it. In the end, what you see is a unique voice, which is what everyone should be striving for.

Triple Nine has enough Heat in it to remind you of diner conversations between De Niro and Pacino, and that Val Kilmer used to be skinny and important. But I didn’t want to see another Heat. I wanted to see something new. And as I flipped through the first 20 pages, I wondered if Triple Nine was going to give me that. Let’s find out if it did…

Chris Allen is brand new on the job. He’s come over from Venice Beach patrol to the LA gang unit, where the big boys play. He’s nervous when he’s teamed up with street-wise veteran Terrell Tompkins, a 40 year old black cop who plays by his own rules, but soon Allen’s showing Tompkins that he’s not the pushover he assumed he was.

Too bad Tompkins has a secret. He rolls with a crew of cops that rob banks, using their knowledge of cop procedure against the very institution they work for, against the very people they swore to protect.

But greed does funny things to people. Somehow, by turning this into a system, they got hooked up with the nasty Richard Lustick, a tall tanned sylista who’s pissed off that they almost fucked up his last job. So now he wants them to make up for it. They’ve gotta hit one of the most heavily guarded buildings in the city, Homeland Security. If they don’t, Lustick’s going to pluck all their little families’ heads off and feed them to the seagulls.

The crew’s fucked. How the heck are they going to get into Homeland Security? Well, one of them postulates, what if they called in a “999?” What’s that, you’re asking? It’s an “officer’s been shot” call. And when it happens, every cop in the city collapses on that area to take down whoever’s shooting cops. Which, of course, leaves the rest of the city wide open for the taking.

The crew has one last decision. Which cop are they going to kill? You guessed it. Poor little Chris Allen. Which seems all fine and dandy at first. Until Tompkins starts liking the guy and wondering if, when the time comes, he’ll be able pull the trigger. That’s all part of the fun. Figuring out if our oblivious hero’s DNA is going to become a permanent part of the LA landscape.

Wonder Woman will be bringing her truth lasso to Triple Nine.

Wonder Woman will be bringing her truth lasso to Triple Nine.

I was worried early on in Triple Nine. There’s no doubt Matt can write. But all I could think about while reading this was that I’d seen this opening heist before. Like in at least a dozen movies and TV shows. It’s the “I love movies” problem all us writers have. We remember those favored passages from movies we’ve watched infinity times, and we want to do the same thing. We want to do what our idols do!

Luckily, Matt’s writing is strong enough to keep us engaged throughout this derivative section. What Matt does well is he doesn’t relegate the character development to our hero, Chris. He gets to know all the players, especially our corrupt cops. You want to know the benefit of doing that? Look at the beginning of this post and read the cast sheet again. That’s why you do it. Because the more developed characters you write, the more good actors are going to want to be in your movie.

You pull this off by remembering that individuals in a group always have their own thoughts, their own opinions. How boring would it be if every one of these bank robbers saw their job the same way? The oldest member of the group, Michael, looks at everything like a business decision, so he has no problems killing Chris. But the youngest member, Gabriel, doesn’t think it’s right, and battles back and forth between whether to stay involved.

The only time a group should think the same way is when it’s so big that you can’t explore everyone individually. Michael Arndt learned this while writing Toy Story 3. He realized it would be impossible to give every single one of the toys their own storyline. He conveyed this frustration to one of the other writers, who pointed out, “Yeah, outside of the big four, the toys think and act as a unit.” As soon as Arndt figured that out, everything about the script became clear to him.

Regardless of Matt’s job with the characters, though, it took way too long to get to the hook here. We don’t hear about the 999 plan until page 52. That’s super-late and should’ve come at the first-act turn at the latest (page 25-30). How do you set up 8 big characters in under 30 pages so you can get to that plot point early? Welcome to the life of a screenwriter. You have to figure it out. Because it wasn’t until we hit the 999 plot point that the script came alive, and more importantly, started to differentiate itself from Heat.

In fact, the structure then became almost genius. We have a strong line of dramatic irony pushing the central story thread. We know that Tompkins is planning on killing our poor hero, Chris, and that Chris is completely oblivious to it. Therefore there’s nothing we can do for him, which drives us nuts (and more importantly, forces us to keep reading in our desperate hope that he’ll figure it out in time).

By itself, this would’ve been fine, but Matt adds an extra layer by having Chris’s uncle, another cop, investigating the opening heist. As the movie continues, he gets closer and closer to finding out it was these cops, which gives us hope that Chris can be saved. This wisely added a sense of urgency to everything.

After the 999 introduction, the only thing that bothered me was the action writing. Action writing needs to be laid out differently than standard description writing in order to visually show that time, on the screen, is moving differently. The problem with Triple Nine was that whether we were describing a character or running down a hallway while being shot at, every paragraph was written the same – in three lines.

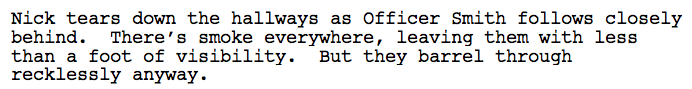

So for example, you’d get something like this (my version).

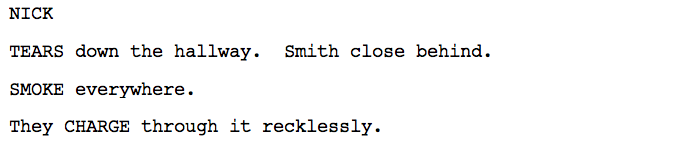

Here’s how that action probably should’ve been written (my version).

The first choice may not seem terrible. But imagine an entire page of that. It would slow the read down to a crawl, which is the exact opposite of how you want the script to read during an action sequence. Of course, every situation will be different, which means there are some scenes where bulkier-written action may work, but the second example is generally how you want to approach it.

The first choice may not seem terrible. But imagine an entire page of that. It would slow the read down to a crawl, which is the exact opposite of how you want the script to read during an action sequence. Of course, every situation will be different, which means there are some scenes where bulkier-written action may work, but the second example is generally how you want to approach it.

Triple Nine wears its influences on its sleeve (Heat, Training Day), but it’s got just enough of a unique take to stand out on its own. And I’m sure the script has only gotten better with time and rewrites. Congrats to Matt for finally getting his ‘produced credit’ wings.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the top reasons I see writers using lots of big paragraphs during action scenes is to lower their page count. Don’t do it. It isn’t worth making your action slow and boring just to hit a low page count. Use other established methods for cutting pages instead (get rid of unnecessary characters, combine characters, combine scenes, etc.).