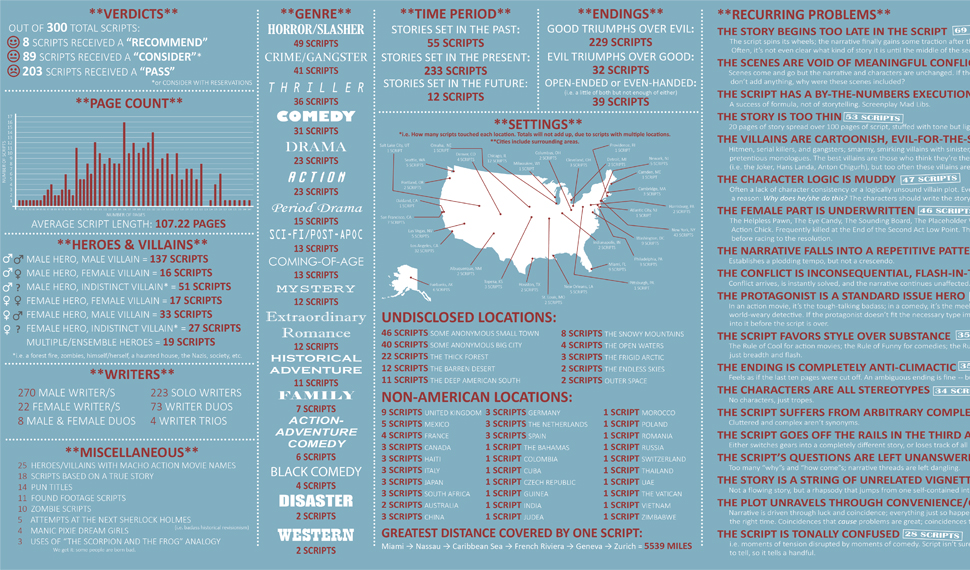

One of the best things to happen to the screenwriting community was this info-graphic. An industry reader read 300 scripts and tracked very specific data on all of them, which allowed him to create a breakdown of all the faults he found. Yeah yeah, that’s kind of depressing. But it’s also helpful! Because guess what? I see these exact same things all the time too and I just say, “Ahhhhhh! Why can’t writers NOT DO these things??” If they understood these pitfalls, screenplays across the world would be so much better. Of course, everybody’s in a different place and we’re all learning at different rates, so yeah, I guess you have to take that into account. But not after today fellas and gals. After today, you are NOT going to be making these mistakes ANY MORE. So, here’s our mystery infographic maker’s TOP 5 mistakes he encountered while reading 300 screenplays, along with my own precious surefire ways to avoid making those mistakes yourselves.

BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The story begins too late in the script.”

(69 scripts out of 300)

Oh my gosh golly loggins, yes, yes AND YES AGAIN. This is SUCH a huge problem in amateur scripts. It’s the radiation poisoning of script killers. What I mean by that is it’s a slow painful way to kill off a script, as the story keeps going, and going, and going, and nothing resembling a story is emerging. This usually happens for a couple of reasons. First, writers can get lost in setting up their characters and world. Sure, setting that stuff up is important, but if you’re not careful, 30 pages have gone by and all you’ve done is set everything up! You haven’t actually introduced a plot. Also, new writers, in particular, use three or four scenes to make a point, whereas pros know to make the point in one. Readers don’t need to be repeatedly told things to get them. Yes, Mr and Mrs. Johnson are having marital problems. But showing four separate fight scenes to get that point across is kinda overkill, don’t ya think?

THE FIX

The first act is the easiest act to structure and, therefore, one you should structure. Somewhere between pages 1 and 15, give us an inciting incident. That means throw something at your main character that shakes his life up and forces him to act. I was just watching the most indie of indie films, “Robot and Frank,” about an old man losing his senses, and his son gets him a robot to take care of him. Guess when the robot shows up? Within the first 12 minutes! So even in an indie movie about old people, the story is STARTING RIGHT AWAY. If they’re doing it, so should you!

SECOND BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The scenes are void of meaningful conflict.”

57 out of 300 scripts

It personally took me a long time to figure this out. “Oh wait,” I realized when I used to spend 72 hour shifts plastered on my laptop screen, “you mean two characters sitting around and talking about life isn’t interesting??” Or a series of scenes with my main character enjoying life could become boring to someone?? It wasn’t until I realized that every single scene needed to have conflict on SOME LEVEL that I truly understood what “drama” meant. Every single scene needs drama, and you can’t have drama without conflict.

THE FIX

Whenever you write a scene, you need to ask yourself, “Where’s the conflict here?” If there isn’t any, add some. I’m going to help you out. Two of the most powerful forms of conflict you can draw on are over-the-table and under-the-table. Over the table is more obvious. Think of two characters confronting each other, a girlfriend who’s just found out her boyfriend has cheated on her. She storms into his apartment and starts yelling at him. They fight it out. Assuming we’re interested in the characters and you’ve set this moment up, it should be a good scene. The far more interesting conflict to use, however, is under-the-table. This is when characters are pushing and pulling at each other, but underneath the surface. For example, let’s say this same girl comes home, but instead of telling her boyfriend what she knows, she acts like everything’s fine. They have dinner, and she slowly starts asking questions. They seem innocent (“What did you do yesterday? Can I use your phone to call a friend?”) when, in actuality, she’s trying to get her boyfriend to admit his guilt, or catch him in his lies. Of the two options, under-the-table conflict is always more fun, but as long as there’s SOME conflict in the scene, you’re good (note, there are other forms of conflict you can use. These are just two options!).

THIRD BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The script has a by-the-numbers execution.”

53 out of 300 scripts

Has someone been spending too much time trying to fit their story into Blake Snyder’s beat sheet? Have you become so obsessed with The Hero’s Journey that you’re starting to pattern your breakfast after it? We were just talking about this yesterday with The Lego Movie script. If you follow formula too closely, it becomes extremely hard for your script to stand out. When I see this, it’s almost always coupled with a boring writing style. The combination leaves the script with no unique identifying value. It is the “anti-voice” script, the equivalent of one of those knock-off Katy Perry songs. The writers most susceptible to this actually are NOT new writers, but writers on their 4th or 5th script. That’s because new writers don’t know about rules yet. It’s the writers who are starting to put in the work and learn how to tell a good story, who then follow the advice a little too literally.

THE FIX

You have to break a few rules. Your script will never stick out unless you take some chances. And actually, the rules you break define your script. For example, using an unlikable protagonist. It goes against conventional wisdom, but if you have a good reason for it and it works for the story, then take the chance. The most susceptible writers to this kind of mistake are SCARED writers. Writers who fear taking chances. They want to play with their story in their safe little bubble. I say surprise yourself every once in awhile. Try something with a plot point you never would’ve normally done. See where it takes you. If you’re surprised, there’s a good chance the audience will be too. And if this is a serial problem for you (everyone’s always telling you your scripts is very “by-the-numbers”), I suggest writing an entire script that’s completely weird and totally different from anything you’ve done before. Tell a story like 500 Days of Summer, where you’re jumping around in time, or Drive, where you’re crafting the story with actions as opposed to dialogue. You’re not going to grow unless you take chances.

FOURTH BIGGEST PROBLEM (tie) – “The story is too thin.”

53 out of 300 scripts

This is usually a problem that begins at the concept stage. Someone picks an idea that doesn’t have enough meat in it. Sofia Coppola’s “Somewhere” is a good example of this. “A guy spends time with his daughter.” When there’s not enough meat, there isn’t enough for your characters to do, and so long stretches of the script go by where nothing happens. Since you’re not a writer-director like Sofia and therefore don’t have funding to make these movies, your scripts can’t afford this pitfall. What it really comes down to is an absence of plot points, the major pillars in your scripts that slightly change the story or the circumstances surrounding your characters, sending it in a different direction.

THE FIX

First, make sure your concept packs a lot of story opportunities. A script like Inception – where teams of people are travelling inside minds – there’s ample opportunity to cram a ton of story into those 120 pages. Also, keep your plot points close together. Something that changes the story slightly or keeps it charging forward should be happening every 10 to 15 pages. So let’s say you’re writing a script about a guy who wins the lottery. On page 20, his ex-girlfriend who dumped him may show up at his door. On page 32, he finds out he’s being sued by someone who says he stole the lottery ticket from him. On page 46, he gets robbed coming out of the bar. Make sure things keep happening consistently during the script to avoid the “thin” tag.

FIFTH BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The villains are cartoonish, evil for-the-sake-of-evil.”

51 out of 300 scripts

This is almost exclusively a beginner mistake. Beginners remember their favorite villains as being over-the-top and quirky in one particular area (an accent, an eye-patch) and think, “Perfect! That’s all I need to do for my villains too!” So they only focus on how the villain acts on the OUTSIDE as opposed to what’s going on on the inside.

THE FIX

With villains, you have to start on the inside. I KNOW people hate doing all this work, but I’d strongly suggest busting out a new Word Doc and writing down as much as possible about your villain. Find out where he grew up, what his childhood was like (was he bullied? Abused? Ignored? Alone? A victim of affluenza?) Any of these could explain why he became the way he did. The more you know about your villain, the less cliché he’s going to be. And remember, the villain always believes he’s the hero. He truly believes in his cause. One of the easiest ways to lead your villain to the cliché troth is to assume he knows he’s bad and loves it. Villains are much more horrifying when, like Hitler, they actually believe what they’re doing is right.