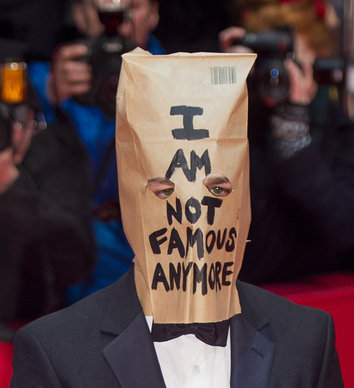

A friend of mine gave me a script last week with that desperate look in his eyes. You know the look I’m talking about. That tired bloodshot I’ve-been-crying-for-seven-days Shia LaBeouf “I Am Not Famous Anymore” eyes-behind-the-paper-bag look? I looked at my friend and said, “Are you okay?” All he responded with was: “Second act… (then he shook his head) second act.” That was it.

For centuries, screenwriters have stood on the precipice of that second act, looked out at its grand canyon of unknowns, and given up right then and there. I honestly believe that the second act is what sends 80% of the writers who come to Hollywood, looking to break in, back to where they came from. Because when you think about it, the first act is easy. You’re just setting up your concept and your protagonist, something you probably already knew just by coming up with the logline.

But the second act is different. That’s because the second act is where you actually have to BE A WRITER. You have to know how to, you know, craft a story n’ stuff. That takes two things. Practice and Know-how. I can’t do the practice for you. But I can give you the know-how. Now what I’m about to tell you is assuming you already know the basics of structure (and if you don’t, you should buy my book, dammit. It’s only $4.99 right now!). First act is 25% of your screenplay, second act is 50%, third act is 25% (roughly). You should know how to give your protagonist a goal (find the Ark, defeat the terrorists, get your life back on track, a la Blue Jasmine) that is driving him through the story, as well as understand how to apply stakes and urgency to that pursuit. Assuming you’re on top of that, here’s the rest of what you need to know.

Character Development

One of the reasons the first act tends to be easy is because it’s clear what you have to set up. If your movie is about finding the Ark, then you set up who your main character is, what the Ark is, and why he wants to get it. The second act isn’t as clear. I mean sure, you know your hero has to go off in pursuit of his goal, but that can get boring if that’s the ONLY thing he’s doing. Enter character development, which really boils down to one thing: your hero having a flaw and having that flaw get in the way of him achieving his goal. This is actually one of the more fun aspects of writing. Because whatever specific goal you’ve given your protag, you simply give them a flaw that makes achieving that goal really hard. In The Matrix, Neo’s goal is to find out if he’s “The One.” The problem is, he doesn’t believe in himself (his flaw). So there are numerous times throughout the script where that doubt is tested (jumping between buildings, fighting Morpheus, fighting Agent Smith in the subway). Sometimes your character will be victorious against their flaw, more often they’ll fail, but the choices they make and their actions in relation to this flaw are what begin to shape (or “develop”) that character in the reader’s eyes. You can develop your character in other ways (via backstory or everyday choices and actions), but developing them in relation to their flaw is usually the most compelling part for a reader to read.

Relationship Development

This one doesn’t get talked about as much but it’s just as important as character development. In fact, the two often go hand in hand. But it needs its own section because, really, when you get into the second act, it’s about your characters interacting with one another. You can cram all the plot you want into your second act and it won’t work unless we’re invested in your characters, and typically the only way we’re going to be invested in your characters is if there’s something unresolved between them that we want resolved. Take last year’s highest grossing film, The Hunger Games. Katniss has unresolved relationships with both Peeta (are they friends? Are they more?) and Gale (her guy back home – will she ever be able to be with him?). We keep reading/watching through that second act because we want to know what’s going to happen in those relationships. If, by contrast, a relationship has no unknowns, nothing to resolve, why would we care about it? This is why relationship development is so important. Each relationship is like an unresolved mini-story that we want to get to the end of.

Secondary Character Exploration

With your second act being so big, it allows you to spend a little extra time on characters besides your hero. Oftentimes, this is by necessity. A certain character may not even be introduced until the second act, so you have no choice but to explore them there. Take the current film that’s storming the box office right now, Frozen. In it, the love interest, Kristoff, isn’t introduced until Anna has gone off on her journey. Therefore, we need to spend some time getting to know the guy, which includes getting to know what his job is, along with who his friends and family are (the trolls). Much like you’ll explore your primary character’s flaw, you can explore your secondary characters’ flaws as well, just not as extensively, since you don’t want them to overshadow your main character.

Conflict

The second act is nicknamed the “Conflict Act” so this one’s especially important. Essentially, you’re looking to create conflict in as many scenarios as possible. If you’re writing a haunted house script and a character walks into a room, is there a strange noise coming from somewhere in that room that our character must look into? That’s conflict. If you’re writing a war film and your hero wants to go on a mission to save his buddy, but the general tells him he can’t spare any men and won’t help him, that’s conflict. If your hero is trying to win the Hunger Games, are there two-dozen people trying to stop her? That’s conflict. If your hero is trying to get her life back together (Blue Jasmine) does she have to shack up with a sister who she screwed over earlier in life? That’s conflict. Here’s the thing, one of the most boring types of scripts to read are those where everything is REALLY EASY for the protagonist. They just waltz through the second act barely encountering conflict. The second act should be the opposite of that. You should be packing in conflict every chance you get.

Can someone PLEASE write a buddy-cop movie about Shia’s bag and Pharrell’s hat?

Can someone PLEASE write a buddy-cop movie about Shia’s bag and Pharrell’s hat?

Obstacles

Obstacles are a specific form of conflict and one of your best friends in the second act because they’re an easy way to both infuse conflict, as well as change up the story a little. The thing with the second act is that you never want your reader/audience getting too comfortable. If we go along for too long and nothing unexpected happens, we get bored. So you use obstacles to throw off your characters AND your audience. It should also be noted that you can’t create obstacles if your protagonist ISN’T PURSUING A GOAL. How do you place something in the way of your protagonist if they’re not trying to achieve something? You should mix up obstacles. Some should be big, some should be small. The best obstacles throw your protagonists’ plans into disarray and have the audience going, “Oh shit! What are they going to do now???” Star Wars is famous for one of these obstacles. Our heroes’ goal is to get the Death Star plans to Alderaan. But when they get to the planet, it’s been blown up by the Death Star! Talk about an obstacle. NOW WHAT DO THEY DO??

Push-Pull

There should always be some push-pull in your second act. What I mean by that is your characters should be both MAKING THINGS HAPPEN (push) and HAVING THINGS HAPPEN TO THEM (pull). If you only go one way or the other, your story starts to feel predictable. Which is a recipe for boredom. Readers love it when they’re unsure about what’s going to happen, so you use push-pull to keep them off-balance. Take the example I just used above. Han, Luke and Obi-Wan have gotten to Alderaan only to find that the planet’s been blown up. Now at this point in the movie, there’s been a lot of push. Our characters have been actively trying to get these Death Star plans to Alderaan. To have yet another “push” (“Hey, let’s go to this nearby moon I know of and regroup”) would continue the “push” and feel monotnous. So instead, the screenplay pulls, in this case LITERALLY, as the Death Star pulls them in. Now, instead of making their own way (“pushing”), something is happening TO them (“pull”). Another way to look at it is, sometimes your characters should be acting on the story, and sometimes your story should be acting on the characters. Use the push-pull method to keep the reader off-balance.

Escalation Nation

The second act is where you escalate the story. This should be simple if you follow the Scriptshadow method of writing (GSU). Escalation simply means “upping the stakes.” And you should be doing that every 15 pages or so. We should be getting the feeling that your main character is getting into this situation SO DEEP that it’s becoming harder and harder to get out, and that more and more is on the line if he doesn’t figure things out. If you don’t escalate, your entire second act will feel flat. Let me give you an example. In Back to the Future, Marty gets stuck in the past. That’s a good place to put a character. We’re wondering how the hell he’s going to get out of this predicament and back to the present. But if that’s ALL he needs to do for 60 pages, we’re going to get bored. The escalation comes when he finds out that he’s accidentally made his mom fall in love with him instead of his dad. Therefore, it’s not only about getting back to the present, it’s about getting his parents to fall in love again so he’ll exist! That’s escalation. Preferably, you’ll escalate the plot throughout the 2nd act, anywhere from 2-4 times.

Twist n’ Surprise

Finally, you have to use your second act to surprise your reader. 60 pages is a long time for a reader not to be shocked, caught off guard, or surprised. I personally love an unexpected plot point or character reveal. To use Frozen, again, as an example, (spoiler) we find out around the midpoint that Hans (the prince that Anna falls in love with initially) is actually a bad guy. What you must always remember is that screenwriting is a dance of expectation. The reader is constantly believing the script is going to go this way (typically the way all the scripts he reads go). Your job is to keep a barometer on that and take the script another way. Twists and surprises are your primary weapons against expectation, so you’ll definitely want to use them in your second act.

In summary, the second act is hard. But if you have a structural road-map for your story (you know where your characters are going and what they’re going after), then these tools should fill in the rest. Hope they were helpful and good luck implementing them in your latest script. May you be the next giant Hollywood spec sale! :)