Drama with a capital “D.” The screenwriter’s enemy.

Drama with a capital “D.” The screenwriter’s enemy.

Today we’re doing something different. One of the biggest problems I see in amateur scripts is bad scene writing. The scenes don’t build, they don’t have any conflict, there’s no inherent drama in the scene. They just kind of lay there like a blanket. They’re forgettable. Which is the worst mistake you can make as a writer.

So the other day, we reviewed a script for Amateur Friday called, “The Cloud Factory.” I was trying to explain to the writer, Angela, in the comments that there wasn’t enough drama in the script. That everything the characters were going through was fairly routine, fairly tame, that nothing was making their journey difficult. She replied that she didn’t want to include over-the-top conflict and was trying for something “subtle.”

Whenever I run into a writer who says this in the absence of conflict, I cringe. While it’s true that there are times when you want to be subtle, in order to keep a reader/audience engaged, you need things to HAPPEN in your script. You need elements pushing and pulling at your characters. You need things to be hard for them in pretty much every scene, although how hard varies per situation. When a writer strips away conflict, they often think they have a delicate, subtle, reserved piece of material, unaware that the reader experiences it as a flat lifeless string of non-events where very little happens.

I speak from experience. I used to do the same thing. I wanted to be reserved. I wanted to be SUBTLE. And yet I was confused every time someone responded to my script with: “Nothing happens here. There’s nothing engaging about the story.” But but but… my characters are on a road trip together, and they both like each other but they’re both afraid to say it, and and and… I don’t want to overburden the story with too much drama cause it will be too on the nose and and and…” Ugh, gag me with a spoon.

Here’s what I think the problem is. Angela, as well as all the writers in her position, are railing against the wrong thing. It’s not that they don’t want drama in their stories. It’s that they don’t want artificial ON-THE-NOSE drama. The kind of capital-D Drama that a writer clumsily jams into the story because the screenwriting books told him to. Inserting drama into your screenplay, into all of your scenes, is like anything else you put into your screenplay. You not only have to do it, you have to do it artfully.

So there are really two skills at work here. First, there’s learning what drama is. And then there’s infusing it into the screenplay in a natural way. Now as I discuss drama here, I’m going to be using the words “conflict” and “drama” interchangeably, as there’s a lot of crossover in the two definitions. But, essentially, conflict creates drama. Now, for the sake of argument, let’s look at a scene that Angela might call too “overly-dramatic,” and see how we can fix it.

Let’s say I have a brother and sister in their 40s who haven’t seen each other (they live on opposite sides of the country) in over a decade. They’re reuniting because their mother just died and they’re home for the funeral. Jacob, the brother, arrives at their parent’s house and walks into the kitchen where his sister, Marla, is doing dishes. Now if you’re subscribing to the “THERE MUST BE DRAMA IN THIS SCENE!” theory that all the screenwriting books tell you to apply, you’re likely to go straight into an argument. “Nice, only a day late to your own mother’s funeral,” Marla says. “Fuck off, Marla! The only reason you came back early is so you could get it in with that loser you’re still obsessed with from high school!” “That ‘loser’ used to be your best friend! And at least I’m DOING something! Have you taken care of any of the arrangements! NO, I didn’t think so!” Etc. Etc.

Yeah, sure, we technically have drama here. But it’s over the top and obnoxious. Drama shouldn’t be thought of as constant yelling or giant obstacles always getting in your characters’ way. Think of it more as a push-pull, an imbalance in the scene between the characters involved. Yes, that will sometimes result in screaming, but more times than not, it’s a tension that hangs in the air, maybe due to a disagreement, or maybe because the characters don’t see things the same way. And if there isn’t that disagreement or issue between the characters, the conflict and drama will come from an exterior source, something pushing on the characters from the outside. This exterior variable won’t always be available to you on a scene-by-scene basis, so you’ll have to set it up earlier in the script. With this knowledge, let’s go back to the above scene and figure out how we can improve it.

Instead of putting Marla at the house, let’s put her at the funeral services for their mother. It’s five minutes before the service starts and lots of people are approaching Marla and offering their condolences. At that moment, Jacob bursts in, sweaty and ruffled. Marla is SHOCKED. Her brother dares to show up five minutes before their mother’s funeral! But, of course, she can’t yell at him. Not with all these people around. Jacob approaches. “Hey, sis.” “Hey, Jake.” She waits until they’re clear for a half second. With clenched teeth, “Nice of you to show up.” “Sorry, I missed my connection.” An old woman approaches: “I’m so sorry about your mother.” Marla puts the fake smile back on. “Thank you, Mrs. Buckley.” Jacob leans in, “Hey, I had to park in a handicapped spot. That’s not going to be a problem, is it?” She glares at him as the priest announces that they’re going to start the procession.

This is just one of many ways you could write the scene. If, for some reason, you need to have them back at the house, maybe Marla has a newborn who’s sleeping in the other room. She can’t wake him, so she must keep her anger in check while discussing Jacob’s tardiness. Or if you don’t want a baby involved, maybe Marla has a husband. And her husband loooooovvves Jacob. Jacob is like the coolest dude to him. So he’s stoked to see Jacob, and after the obligatory “I’m sorry about your mom,” he starts talking about them going hunting tother, wanting to know all about Jacob’s cool job. In the meantime, Marla is boiling, but doesn’t want to ruin her husband’s excitement, so she keeps it cordial. OR if you don’t want a third character to interrupt the scene, maybe these two are just not confrontational types. They keep everything buried – always have. So they have a very normal conversation, but the subtext runs deep. The two attack each other in more passive aggressive ways, despite the surface level conversation being cordial.

I think my problem with The Cloud Factory, was that the version of this scene that would’ve appeared in that script wouldn’t have had any issues or conflict at all. Marla and Jacob would’ve been on solid terms. They both cared a lot about their mom. Maybe Jacob was a little late showing up, but it wasn’t his fault, so Marla forgave him. Sure, a writer could argue, “Well I didn’t want any tension here. I just wanted a normal scene.” To that I say, okay. That’s fine. Every once in awhile, if it’s right for the story, there’s no conflict. But if you string together a BUNCH of these scenes, then it becomes a problem. Long passages of no drama – a drama drought – is the surest way to bore a reader.

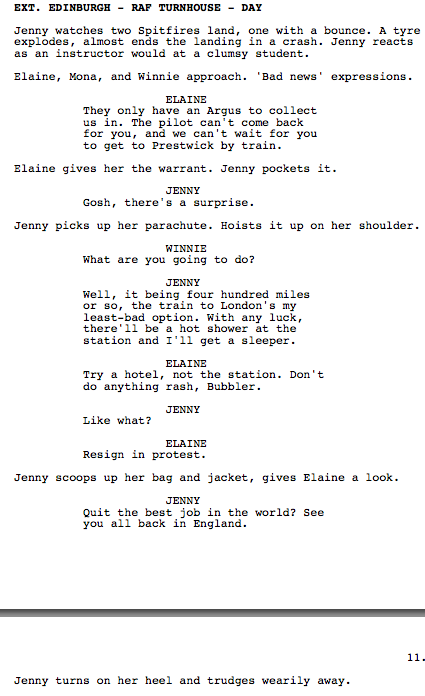

With that in mind, let’s look at one of the scenes in The Cloud Factory. In the scene, Jenny, our hero, is grounded in Edinbergh. The other women in her group are taking a flight to the nearest base, but they don’t have room for Jenny (I’ve forgotten why Jenny is being singled out as having to stay, but we’ll assume it’s for a logically explained reason). Here’s the scene as written:

This is a scene that’s easy to screw up. It’s a short scene that’s all exposition, but necessary. We need to explain that they don’t have room for Jenny and then explain what she’s going to do next. Writers often see this and think, “Well, it’s short, so I’ll just throw it in there, even though it’s boring and all exposition.” You NEVER want to include a drama-less scene, especially one that’s all exposition, if you can write a more interesting dramatized scene instead. The first thing I noticed here is how passive the setup is to the scene. We’re getting information about Jenny not making the flight after the fact. You could try to force some conflict into this scene, like one of the girls not liking Jenny and therefore enjoying the fact that she can’t come, but it would feel false, like a scene out of Mean Girls.

The issue is that the scene isn’t taking place at the right spot. We need a scene setup that invites more conflict. If I were developing this with Angela, I’d have Jenny thinking she’s on the next plane going out with the three other girls. So she’s all packed up and ready to go. She goes to the plane with the others, and the pilot pops out. “Hold up hold up. What’s going on here?” They explain who they are. “No, I was told only three were coming. That’s all I have room for.” Now the girls are stuck in the precarious position of having to leave someone. It’s an awkward moment, but it creates conflict. Who’s worthy of going and who isn’t? Everybody makes their case. In the end, Jenny loses out (maybe gets screwed over). “I’m sorry, Jen. What are you gonna do?” “I guess I could take a train to London…” (etc. etc., this is where you put your exposition in). As you can see, we created drama in two places. First, with the pilot not letting all of them on, and then between the girls, who have to decide who’s staying. Way better scene, right?

Now I’m not saying there will never be quick exposition-only scenes in your script. I’m saying that you should always try to dramatize them if you can. Look at all your scenes on an individual basis, like I did above, and ask if there’s any drama/conflict there. If not, ask yourself if there’s another way you can do it. How bout you guys? How would you rewrite the above scene?

I should point out that conflict isn’t the only thing that creates drama. It’s just the main thing. But urgency creates drama (have you ever noticed that when you’re running out of time, nerves get nervier, patience gets thinner?). Stakes create a lot of drama (if someone’s job is on the line in a scene, the scene is going to have a lot more drama than if everyone’s job is safe). How personal the issue is creates drama (I care a lot less if somebody I barely know tells me they’re never going to talk to me again than if it’s my own sister). In general, with every scene, you’re trying to make things hard on your characters. The intensity of that pressure will vary depending on the scene, the situation, and the characters involved. But like I said above, if everything’s going well for your characters the majority of the time – that means long stretches of no tension, no pressure, no consequences, no issues, no subtext – you’re looking at an increasingly bored reader. You need to add drama to your scenes and to your script in general.