I was going to do my yearly post of the best movies of the year, but you know what? I don’t wanna. “Best Of” lists are boring to me right now. And if I’m bored, then my posts are definitely going to be boring. So instead, I’m going to share some screenwriting advice with you. Now that excites me. Helping all of you become better writers. For those who just have to know, however, here are my Top 10 films without explanation.

10)Captain America: Winter Soldier

9) The Equalizer

8) Blue is the Warmest Color

7) Guardians of the Galaxy

6) In a World

5) John Wick

4) Gone Girl

3) The Skeleton Twins

2) Philomena

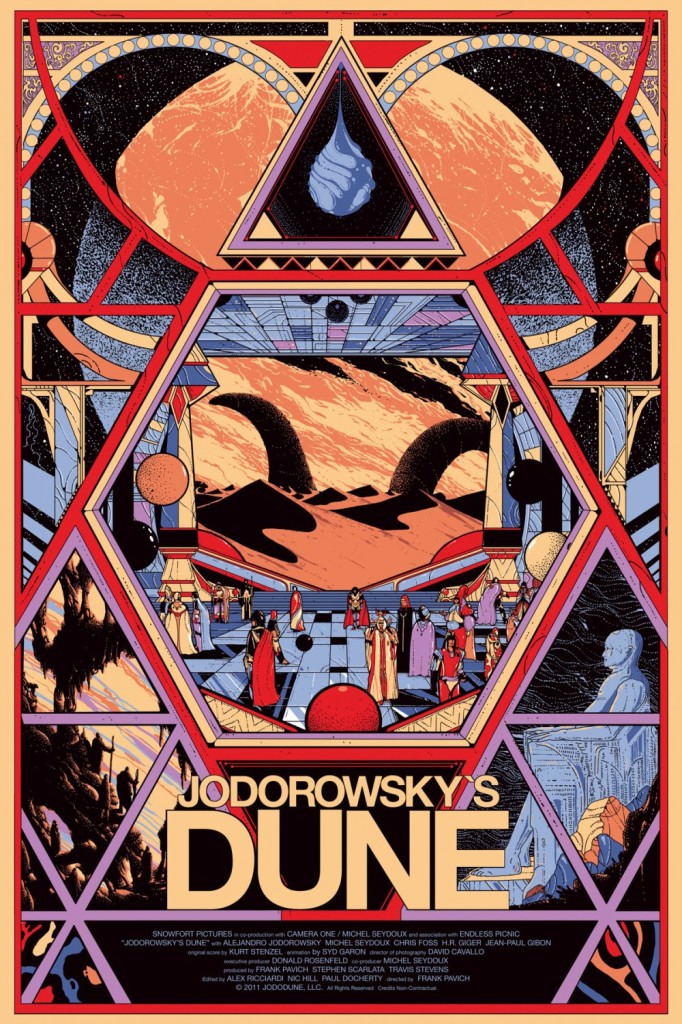

1) Jodorowsky’s Dune

Did not yet see: Nightcrawler, Boyhood, The Imitation Game, Foxcatcher, Lucy, Whiplash.

Now let’s talk about something that can actually help you. How bout a hefty dose of DIALOGUE ADVICE? Yeah! Nobody offered you that over the Christmas holiday, did they? You see, the other day, I was giving notes to a writer, and the dialogue in the script wasn’t up to par. Dialogue is always the hardest thing to help a writer with because it’s the subtleties that make it or break it. And most subtleties are intrinsic, making them hard to dissect and explain. This is what people mean when they say some writers have an “ear” for dialogue. What they really have is an ear for the subtleties of conversation.

So I had to take a few hours off, go through old sets of notes, pick out tips I’ve given before, look for new solutions specific to this writer’s problems, and package it all in a way that would help this writer dramatically improve his dialogue. The end result was more comprehensive than I expected, so I thought I’d share it with all of you. With that, here’s what I wrote…

The big weakness here is dialogue. There are too many on-the-nose, melodramatic and cliché lines. Here’s an example from Hunter and his son, Nicky (note to readers – part of the backstory here is that Hunter’s wife died).

Nicky: “Wish I could’a protected her that day…”

Hunter: “Me too, Nicky… me too.”

Let me ask you this. Is there any doubt that father or son wished they could’ve done more to save mom? Of course not. Therefore, to say it out loud is the definition of “on the nose.” This is followed by an extremely cliché echo-line. “Me too, Nicky… me too.” The echo-line has been used so many times throughout history that by this point, it’s only used as parody. I’ve personally seen the guys on South Park use it endlessly. Stay away from on-the-nose lines (characters saying exactly what they think/feel) and any line you’ve seen used more than a handful of times in other movies/shows.

Here’s another line (note to readers: our protagonist, Colin, accidentally killed a child while trying to save a group of people. Claire, our romantic interest, has just tried to convince Colin that it was an accident and there’s nothing else he could’ve done).

Colin: “He was just a little boy, Claire! His whole life ahead of him.”

Take note of how familiar and melodramatic this line is. It feels like something out of a soap opera. Also, once again, we know he was a little boy. We know he had his life ahead of him. Therefore, stating it out loud is on the nose and obvious. If you find your characters saying exactly what they’re thinking, exactly what they’re feeling, or anything that’s obvious, you’re probably writing bad dialogue. So how do you make this line better? In this instance, I wouldn’t have had Colin respond at all. As Claire tries to convince him it was an accident, I would’ve had him take it in. A look of frustration or disagreement, then, is all you need to convey his feelings on the matter. Often times, the absence of dialogue is the best dialogue option.

Overall, the dialogue here needs to be more unpredictable. It needs to be more natural and messy. Moving forward, I would suggest studying dialogue on a much deeper level. Start by writing down all your favorite dialogue-centric movies, then reading those scripts and noting where you liked the dialogue, then trying to figure out WHY you liked the dialogue. For example, a writer whose dialogue I’ve come to enjoy always inserts a unique phrase where a generic one would typically be. So instead of writing, “Joe went bar-hopping,” he might write, “Joe’s down at the strip of broken dreams.” Yet another writer reminded me how important specificity is when it comes to dialogue. A character shouldn’t say, “I need cereal.” He should say, “I need Tony the Tiger.” Paul Thomas Anderson, who many consider to be a dialogue master, says he rarely lets his characters finish sentences. He constantly has them interrupting before the other character finishes, as that’s more like real life.

I would go to coffee shops and eavesdrop and write down, verbatim, what people are saying to each other. Pay attention not just to what’s being said, but what’s being implied, aka, the subtext. “That’s a nice new purse,” doesn’t always mean, “That’s a nice new purse.” It might mean, “Looks like your sugar daddy’s treating you well.” Compare all this dialogue to your own dialogue. Figure out why yours doesn’t have the same naturalism.

I would spend every day writing a few practice dialogue scenes. Experiment. Take chances. Be creative. For example, write an entire scene with dialogue you’ve never heard before. Write an entire scene focused on subtext. Write an entire scene focused on suspense. Compare your scenes to scenes from professional scripts and note the differences. Pay specific attention to word choice. What words are the professionals using that you’re not?

Try to create scenarios where there’s conflict or tension between characters, as both result in more interesting conversations. Create secrets for your characters, so there’s subtext to what they’re saying. For example, in your script, Claire tells Colin right off the bat that she’s dying. Instead, what if you only give this information to the audience, and now when she meets Colin, she DOESN’T tell him she’s dying. Now the dialogue will be a lot more interesting. We’ll fear for Colin as he falls for Claire, knowing he’ll be devastated when he finds out the truth. Dialogue is one of those things, unfortunately, that doesn’t have a quick fix. It’s the culmination of a lot of small discoveries. But it’s not an area you can hope readers will overlook. Bad dialogue is one of the easiest ways to identify an amateur screenplay, so you have to put a lot of effort into getting it right.