Yesterday was all about the strong dialogue.

Conversations were popping off the page throughout Voicemails for Isabelle. They were fun. They were vibrant. They were clever. Easily top 5 dialogue I’ve encountered all year.

What’s frustrating, though, is that a lot of what you saw yesterday is God-given talent. Some writers understand how people speak better than others.

I know this because I’ve read hundreds of scripts that have tried to do what McKendrick did yesterday and not even come close.

You know in movies where the characters have been friends all their lives but the actors just met a day ago because it was their first day on set? They’re supposed to act effortless and natural around each other but how can they when they barely know each other? That’s called forced camaraderie. And it’s the same feeling a reader gets when a subpar dialogue writer is trying hard to write witty dialogue between characters. It doesn’t feel honest.

So what should you do under those circumstances? Quit screenwriting?

No, of course not. That would be silly. Like I said yesterday, only 20% of the scripts I read have awful enough dialogue or awesome enough dialogue that I notice (and most of that 20% is the awful kind). The other 80% is decent enough that it doesn’t bother me either way.

As long as you still know how to tell a great story or still know how to write interesting characters or still know how to come up with a strong concept and execute it solidly, you don’t need to knock your dialogue out of the park. Especially if it’s in a genre that doesn’t need stand-out dialogue, such as horror.

But luckily, there is a trick you can use to create better dialogue scenes, even if dialogue isn’t your forte. I call it the Third Variable.

Naturally, gifted dialogue writers only need two characters and a keyboard – or “two variables” – to write great dialogue.

While us not-as-gifted writers may not be able to play at that level, we can add a THIRD VARIABLE to the scene which intrudes upon the predictable two person interaction to, in turn, elevate it.

The most obvious example of this is to add a third character to a scene. Say your husband and wife characters are arguing with each other one morning. We’ve seen a million arguments in movies so it’s difficult to do anything special with that dialogue. But let’s say you add a maid to the scene. She’s cleaning in the same area that they’re fighting in. This would then result in them speaking around some things. Or being more selective in what they say.

You may not realize it yet, but this is the secret to good dialogue. Characters who can say whatever they want is rarely interesting. I guess for certain sitcom characters, like Sheldon from Big Bang Theory, it works. But in movies, you want to restrict your characters in some way so that they have to dance around the things that they would normally say. This is where you find more creative choices in dialogue because you’re not allowed to use default responses.

By the way, I’m calling it the third “variable” rule as opposed to the third “person” rule for a reason. Because an extra character isn’t the only way to exploit the Third Variable. You could also exploit it, for example, with a TIME RESTRICTION.

Let’s say our same husband character is taking his daughter to school. The two get in an important discussion. The dad wants to explain to his daughter that he and her mother are fine. The problem is, they’re a minute away from school. And the daughter is getting more upset by dad’s explanation, not less.

Time now plays a critical role in the dialogue because the dad has to rush the explanation when this is clearly a discussion that needs more time to be explained productively.

You notice the common factor here? Once again, the third variable is keeping our hero from being able to say the things he wants to say in the way he wants to say them. That’s where you want your characters to be in a dialogue scene. You want them unable to say the things they want to say, which forces the writer to come up with more interesting choices.

Yet another third variable could be the weather. Romeo and Juliet having a conversation on a sunny afternoon is going to look different than if it’s 10 below zero outside. They’re going to be a lot less interested in exchanging love soliloquies than they are jamming their fingers on their frozen iPhones to get their Uber to show up faster.

Same idea, guys. The weather is keeping our characters from saying what they would normally say.

I’ll give you a personal account of how I accidentally stumbled upon a third variable moment without realizing it. I once wrote a script where the two main characters, an older man and a woman, were roommates. One night, he had to come home and explain to her that he couldn’t afford his half of the apartment anymore and was going to have to move out.

I wrote the scene 5-10 times and it was always boring. Boring on-the-nose dialogue. It was like the reader already knew the conversation so what was the point in me writing it? I might as well have written “You know what they’re going to say here so fill it in yourself.”

In the next draft, I did more work on the female roommate and realized she was a big book reader and that she had a book club that met at their apartment every week. So in the next pass of the script, I thought to myself, “why not put her book club meeting in the scene?”

This time, the male roommate comes back to a big book club meeting. The book club then BECAME THE THIRD VARIABLE. All of a sudden, the scene became a lot more interesting. You had weird, funny, and one horny, book club members chiming in, and just like that, the dialogue came alive.

Just being aware of the Third Variable Tool is going make you a better dialogue writer. But the power of the Third Variable works best when the variable itself is creative and when the way you implement is creative.

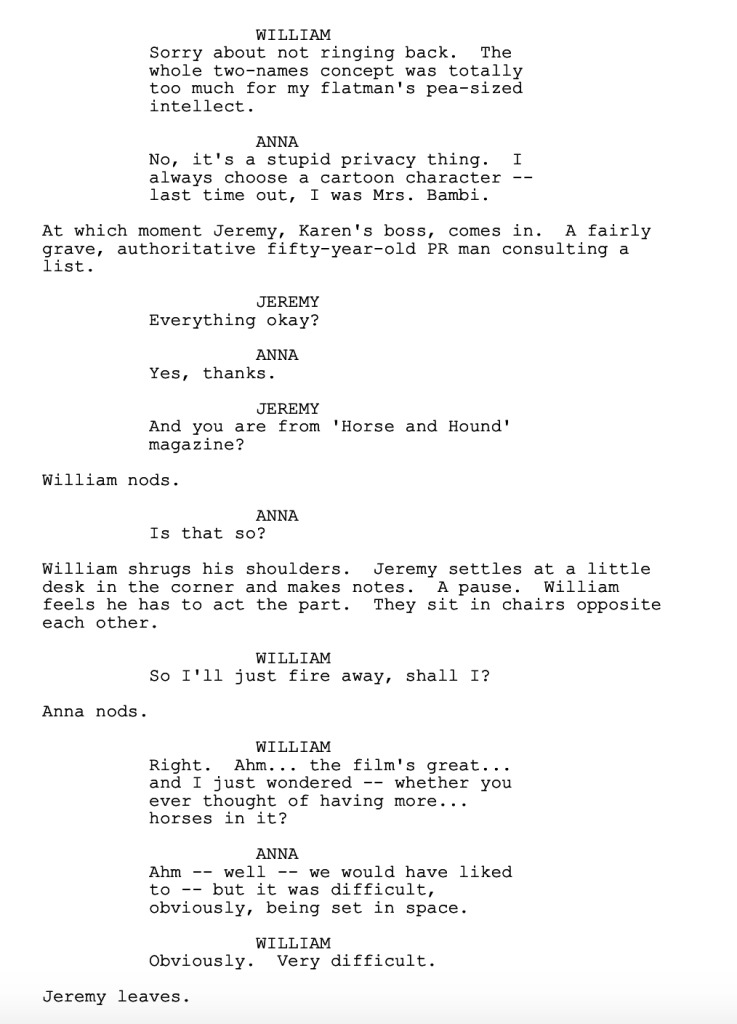

To this day, one of the best THIRD VARIABLES I’ve ever come across was the first date scene in Notting Hill. 99% of writers would’ve written Hugh Grant and Julia Roberts’ first date at a fancy restaurant with a lot of people gawking. It’s such an obvious setup for their situation (which should always act as a red flag that you shouldn’t write it).

Instead, Julia Roberts has Hugh Grant unknowingly come to the PRESS JUNKET for her latest movie. The press junket then becomes the THIRD VARIABLE. Every time he tries to talk to her, someone gets in the way. A curious fellow journalist. An actor who needs to be interviewed. The junket coordinator who keeps peeking in on their only private conversation (“Three minutes left!”). That’s what I mean when I say a creative third variable.

An uncreative third variable in that circumstance would’ve been – oh I don’t know – Hugh Grant’s parents or something.

What I mean about how creatively you implement your third variable is how cleverly it interrupts the scene’s key interaction. Let’s go back to my first example from this article. A married couple with a maid is in the room. In a pinch, this can get the job done. But there’s no connection between the variable and the primary characters.

What would be better is if our married couple was having troubles due to the husband’s recent infidelity. From there, you would make the maid extremely attractive. Now, we have this wife who’s very sensitive to her husband’s interest in other women and, to make matters worse, while they’re hashing this problem out, there’s a very attractive female in the room. It’s going to give you that little extra kick to the conversation.

How often should you use the Third Variable? Technically, you can use it for every single dialogue scene as long as you do a good job varying the third variable. If you only ever add a third person, it’s going to start to feel manufactured. You have to throw in time. Or weather. Or a party. Or have one of your characters deliberately stop in the middle of an intersection clogging up traffic so that all of the cars are honking at you to move – write us a conversation in that environment (Training Day).

But you should definitely mix in straight dialogue scenes. I was just watching The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel because I remembered the dialogue being so memorable in that show. And while they do use a lot of Third Variable scenes, there are plenty of one-on-one conversations as well.

You just have to make sure you’re doing the basics right in those scenes so that you’re giving yourself the best chance to write good dialogue. One character wants something in the scene. Usually, the other character doesn’t want to give it to them. This creates conflict within the interaction, which in turn leads to dialogue with more pop to it.

And just try not to write the dialogue exchange that 99 out of 100 writers would write. Every time you walk into a scene, you’re writing a situation that has been written thousands if not millions of times already. Figure out what the most common version of that conversation looks like and make sure you don’t write that.

I can give you one last tip to avoid that. In the middle of your dialogue scene, have one of the characters say something that nobody expected them to say (even you, the writer!). That will send your dialogue down an unexpected direction, and that’s when dialogue comes alive. Dialogue is rarely interesting when everyone says what we expected them to say.

This happened in the episode of Mrs. Maisel that I researched. Mrs. Maisel was in court about her lewd stand up routine that sent her to jail. All she has to do, her lawyer tells her ahead of time, is nod and say thank you. So the first half of the scene goes according to plan. But when the judge brings up how stupid it was for Mrs. Maisel to do what she did, she can’t hold back and explains why there was nothing wrong about what she did at all. The dialogue in the rest of the scene was great. All because a character went in an unexpected direction.

I love the Third Variable tip. Whenever you’re struggling to make a dialogue scene work, try this out. I guarantee it will improve the dialogue. Go ahead and share your favorite third variable scenes in the comments. I want to learn about as many of these examples as possible.