Genre: TV Pilot – 1 Hr. Drama

Premise: Club Lavender follows a transgender cabaret singer forced to go undercover for the FBI to infiltrate a gay private club run by an alleged communist gangster.

Why You Should Read: My script received a recommend on the trackingboard.com in 2016 and yet nobody would touch it because it was too niche. This was when transgenderism was beginning to get mainstream news after Caitlyn Jenner’s recent reveal. Now it’s a year later and I believe it’s the right time for more daring television surrounding controversial matters. Most importantly, my script exists in the new age of television and as such, takes a no hold’s barred approach to the aspects of story realism and grit. So read at your own caution.

Writer: Sylvester Ada

Details: 68 pages

One thing we need more of in Hollywood is unique voices. Most screenwriters tend to come out of that upper middle class white male demographic. The problem is, since most of these people were brought up the same way, they tend to see the world the same way. Not all of them. But most of them. Which is one of the reasons all Hollywood movies look and sound the same.

A couple of weeks ago we had a writer from rural North Dakota, Logan. And you could feel the uniqueness and the truth in his voice when he wrote. He was great at writing about isolation because he grew up isolated. And this week, we have someone who clearly had a different upbringing because nothing you read here feels familiar. This is a unique script and a unique voice. And we’re going to figure out if that translates into a good story.

Sydney Towne is a 20-something female singer at a beat-up old club in 1960s Queens, New York. It’s clear from the way she sings, she’s too talented to work here. But we get the feeling that a multitude of secrets keeps her from singing at the nicer clubs up the street.

After her performance, Sydney gets changed, and that’s when we realize Sydney is actually a man. She heads home for the night, but on the way a few thugs corner her and ask her for a “private” performance in an alley. As they toss Sydney around, debating whether she’s a woman or a man, a man in a mask arrives and puts a bullet in all the thugaroos.

He reveals himself to be James Pompero, the owner of a high class joint uptown called “Club Lavender.” He wants Sydney to work for him, even driving her there and taking her on a tour. That tour reveals a complicated club where gays, transgenders, and straight men with secrets, hide behind masks and enjoy a world they must keep private from their everyday lives.

Sydney wants no part of this but James is nothing if not persistent. Things become complicated when it’s revealed that one of the men James killed was Tiny Pete, the son of Columbo mob boss Carmine Perisco. New York Police Commissioner Arthur O’Reilly comes in and asks Carmine to let them find out who did this. But you get the feeling Carmine’s going to do his own investigation.

The remainder of the script follows several cops, as well as Carmine’s men, as they try and figure out who killed Tiny Pete. Since everyone has something to hide, they’re all trying to reconfigure the variables so that they don’t get exposed. Meanwhile, Sydney’s got to make a decision soon. Or James might nudge all these Sherlock Holmses in her direction. It’s starting to sound like there was never a choice in the first place.

Club Lavender is a really well-written script. Probably one of the best written scripts of the year. But remember, there’s a difference between “well-written” and “well told.” I’m more interested in a well-told story. And I’m on the fence about how I feel with Club Lavender in that regard.

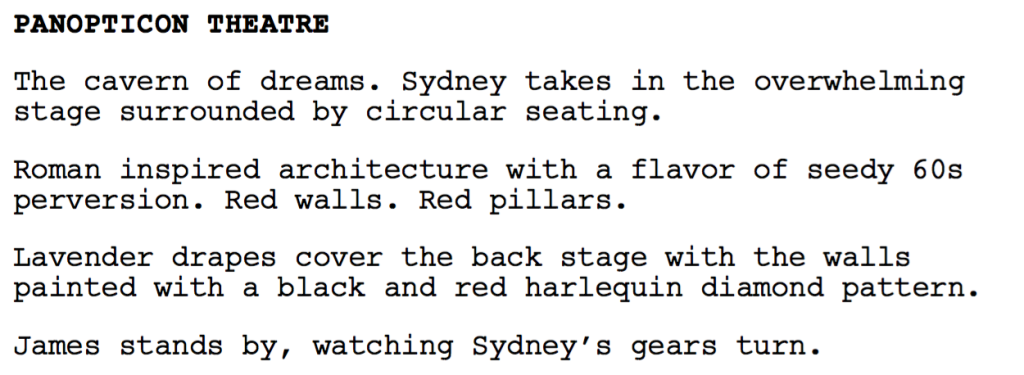

While I figure it out, let’s talk about specificity. Specificity is an advanced screenwriting tool one uses to make their world believable. If you were a beginner screenwriter and you were to describe Club Lavender, you might write, “It’s a throwback to the clubs of the 60s, a beautiful arrangement of old-time elegance, along with some hip trim.” The problem with this description is there’s no specificity. So we don’t believe in the club.

Here’s how Sylvester describes it:

Can you see the specificity there? With that specificity comes our belief in that world. You might be saying, “But Carson, I thought the writing in a screenplay was supposed to be sparse.” It is. Except when you’re describing the important things, the things that matter to the story. This show is titled Club Lavender, so I better get my money’s worth when it comes time to describe the place.

Another thing that Club Lavender reminded me of was that, when writing a pilot, you need “THAT SCENE.” “THAT SCENE” is the scene that shows us why your hero is worthy of watching for 70 hours, AND that’s a good memorable scene in its own right, the scene people are going to be talking about afterwards.

That scene in Club Lavender comes in the form of Tiny Pete and his cronies trapping Sydney in the alley and trying to get her to strip so they can figure out if she’s a man or a woman, and then a masked man shows up and kills them all. That scene had everything – a horrifying situation, suspense, our hero fighting back with everything she had, a mystery person showing up and killing the thugs. It was the moment for me when I truly committed to the script.

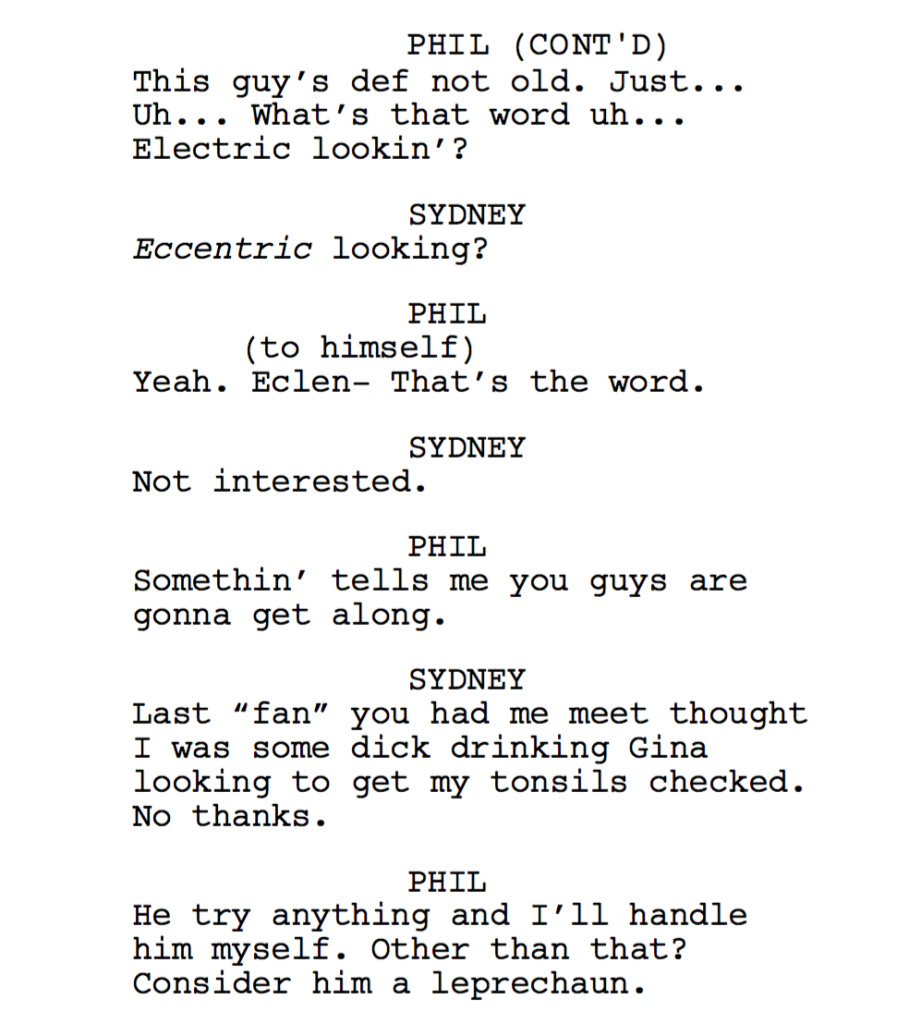

But the best thing about Club Lavender is the dialogue.

It’s creative. It’s unique. I’d go so far as to say every dialogue chunk was its own little work of art. And I say that because you can tell Sylvester put everything into every single line. Lesser writers take scenes off. There isn’t a single dialogue scene that was taken off here. It’s all strong.

With all that praise, this script must be getting a genius rating, right Carson? Not so fast. There are a few missteps that kept me from loving Club Lavender.

The first is that the plotting starts to get clumsy towards the end. I was having a particularly hard time following the cops. Writers have to remember that readers lump cops in together. Every time a new cop is introduced, we’re thinking, “Okay, that’s cop number 6 now.” They don’t get that memory bank differentiation that comes from a character having their own unique job.

So when some cops are trying to destroy evidence, others are trying to kidnap Sydney, others are trying to help her, there was another cop I think who was also on the take or something. It becomes easy for us to mix those people up unless we’re taking meticulous notes. And if you’ve got us doing that, you’re making us work too hard. This is why I always say, use as few cops as you can get away with. And for the ones you keep, make sure their names are all really different. And the way they look, act, and talk is all really different. Otherwise, I’m telling you, we’re going to mix them up.

Another thing I had a problem with was this whole communist thing. I didn’t get it. If this script was just about important powerful people – criminals and good guys alike – hiding in this club, I would’ve liked that. But we’re also supposed to believe that these people are communists? Or some of them are communists? Or is this a time when the U.S. was calling gays and transgenders communists even though they weren’t? I didn’t understand it. And since that was the big ending reveal, I was left feeling limp. A pilot is supposed to have you on the edge of your seat ready for episode 2. I was not there after this ending.

It seems to me like that’s a really important story point for Sylvester so I’m not going to tell him he needs to ditch it. But I would. I think it’s unnecessary. You have a club where everyone is hiding something, a Godfather like mob-war subplot, and lots of fascinating characters. What else do you need? If you want to keep the secret agent thing, then have her working for the cops as an informant rather than for the FBI.

With that said, this is definitely worth a read. I’m sometimes asked the question, “How do I know when my writing is at a professional level?” And the only answer I can give them is, “When someone wants to pay you to write.” And I would pay, in a second, for Sylvester to a dialogue pass on one of my scripts.

Think about that guys. If you needed to pay someone to write an idea of yours and it couldn’t be you, whose writing is impressive enough in your eyes, that you would actually pay them money out of your own pocket to write it? Now turn that question back on yourself. Do you believe someone, after reading your script, would pay you to write something for them? If you’re good at being objective, that question can help you understand where you’re at and what you need to work on to get to that paycheck.

Script link: Club Lavender

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Just drop the heater and step away from the lady, before we have one of those closed casket conversations.” Come on, I dare you to write a line as good as that.