Genre: Spy/True Story/Thriller

Premise: In 1985, when CIA Officer Aldrich Ames sells what he believes to be useless intelligence to the Soviets to pay for his divorce, he inadvertently sets off an international Cold War crisis that finds him heading up a special CIA unit — a unit created to find out who sold secrets to the Soviets.

Why You Should Read: Being true, it’s a spy story that’s more grounded than most, but also barely believable in how it plays out. There are absurdities that could only come from real life. It’s based on research drawn from the Senate Committee report published after Ames’s arrest, as well as testimony from the Soviet Intelligence Officer who ran Ames as an agent. Personally, I could use some writerly interaction with my work as I’ve been more-or-less blocked for the better part of a year, and need to get back into the flow. I’d be very grateful for any and all response to the script. Thanks.

Writer: Will Alexander

Details: 133 pages

Man, I had one heck of a long day today. I had to do 10,000 things around town. I then had to do a ton of reading. Some analysis. And then, when I was dying for some sleep, I still had to get this post up. I bring this up as a reminder that sometimes – in fact, probably most times – these are the conditions your script is being read under. If you’re not turning in a draft of the latest Marvel movie to Disney, your priority level is, unfortunately, pretty low. All the more reason to grab the reader right away and make them forget about all of that. That’s what writing is. It’s creating a story so compelling that whatever the reader has going on in their life, in their head, all of that disappears because they’re sucked into your world. So let’s see if Will can pull that off. I’m opening the script now…

It’s 1985. Washington D.C. Aldrich “Rick” Ames, is 42 years old and one of the better CIA agents. He’s in the midst of a divorce and fighting with his wife over the settlement. It’s looking more and more like he’s going to have to pay her a lot of money. Meanwhile, he’s fallen in love with a Columbian woman named Rosario. Rosario likes to tally up $1500 monthly phone bills to Columbia.

Ames’ main contact in the Soviet Union – who, by the way, we’re in a nuclear arms race with – is a man named Sergey. It’s not entirely clear to me why he meets with Sergey, but as best I can tell, he makes his superiors believe that Sergey is a good contact who he can convert into a spy. This allows him a lot of face time with Sergey, and, at a certain point, Sergey starts asking for info. A light bulb goes off for Ames. He can demand 50 grand, give Sergey a couple of names, and not have to worry about money anymore. Which he does.

What he doesn’t know is that Sergey has already figured him out. Rosario is a money succubus. This 50 grand won’t do anything. Which means Ames will have to come back for more. And when he comes back for more, Sergey will ask for more names. And that’s exactly what happens. The CIA is baffled when all of their spies start getting caught. They figure there’s a mole but nobody suspects Ames at all for some reason. Ames continues to trade contacts for cash to the tune of 4 million dollars. A decade later, after he’s settled into the high life, they catch him. Ames is said to be responsible for 10 CIA agents’ deaths.

Okay, I’m about to go on a rant here. You’ve been warned.

133 pages?

If there’s a top 5 rules in screenwriting, “Don’t write a script that’s over 120 pages if you’re an amateur screenwriter,” is in it. It might even be number 1 on the list. Because what happens is what happened today. I’m overworked. I’m tired. But I have to read this script. I open it up. And then I see that number. And once I see that number, I’m enraged. My night has just gotten a lot longer.

It’s not just that. It’s that when you have a long script and a reader with not a lot of time, they’re not going to be able to give your script the focus it requires. When they encounter something they don’t understand in your story, they’re not going to go back and reread it. They’re going to keep going. And in a script like this? With unfamiliar Russian names and the need to keep track of agents and double-agents and who’s lying and who’s not. You’re digging your own grave.

So, look. You can be the person who ignores this stuff and does it your own way. It’s not like no one’s ever succeeded by breaking the rules. But I’m just trying to help you guys avoid basic pitfalls that infuriate people in the business. I want you to succeed. So I’m going to keep reminding you about this stuff.

And by the way, this occurs in contests as well. I know some people will say, well this is more of contest script anyway. Okay, tell that to the guy who has to read 4-5 contest scripts a day.

Moving onto the script, here’s what I liked. There’s a sophistication to this script. There’s a love of the genre. There’s a crazy amount of attention to detail. The writer swung for the fences. He wasn’t trying to write Zombie Vampire Date Night From Hell. This is an Oscar aspiring script. On top of that, this is actor and director bait of the highest order. Steven Spielberg signed onto a similar project, Bridge of Spies. So the counter-argument to everything I just said is THAT. This project has tremendous upside.

If it’s well-executed.

Was it well-executed?

Well, I’ll put it like this. This is a great character-study. And Ames is a perfect metaphor for America. We’re often assumed to be a nation of greed. And that’s what we see play out here. So when I look at the movie as a whole, I like that component of it.

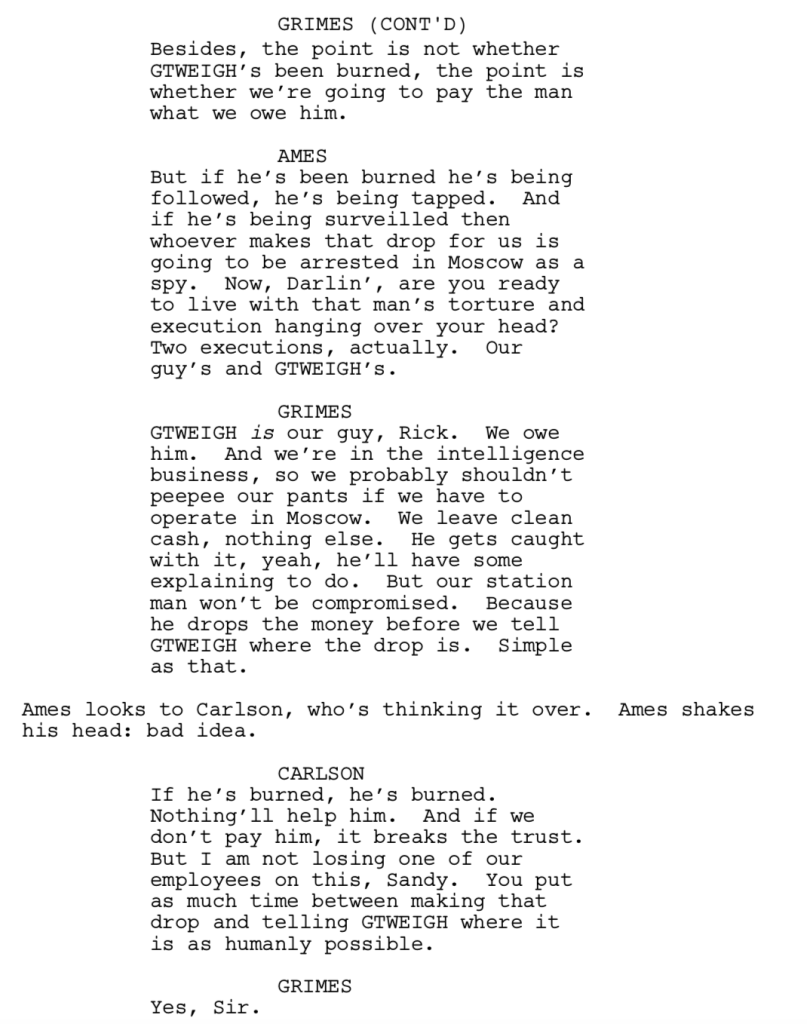

However, when I look at its individual parts, it wasn’t an easy read. You’d get a lot of long scenes with men sitting down talking. And in those scenes, the chunks of dialogue would not be 2-3 lines long. They would be 10-15 lines long (not all of the time, but enough to say it happened frequently). This verbosity took its toll on the pacing and overall enjoyment of the script. In fact, I think you could eliminate 10 pages here just by cutting down how much everyone says every time they open their mouth.

Also, the story didn’t evolve enough. I got the same feeling in a scene on page 80 as I had on page 40. The boiling pot of Ames getting closer and closer to being discovered kept the story moving. But there was a lack of differentiation to the scenes. It felt like I read 20 scenes between Ames and Rosario that were exactly the same. And Ames always seemed to be sitting at a table talking to someone. I don’t know. I wanted more variety in what I was seeing.

One of the skills that’s important for a screenwriter to remember is the skill of condensing. Anybody can write some rambling 160 page story. But one of the reasons they need screenwriters is because non-screenwriters don’t know how to condense story. They don’t know what parts can be thrown out, what parts can be combined, what characters can be jettisoned. This is what great screenwriters are masters at. If a director comes to them and says, “Look, I don’t have the money to shoot all three of these scenes. Can you write a scene that combines all of them?” they can do it in a heartbeat!

And I get that there’s no rules. But, at the same time, you can’t be too precious. You have to think of the reader and the pacing and make tough choices so that the script is not just an accurate telling of your story, but an entertaining telling of it.

This is a strong topic. I can totally see a studio wanting to tell this guy’s story. In fact, I can imagine the trades write up of it and I wouldn’t blink an eye if I saw it. But for me it was too big, too repetitive at times, and probably needed a couple of “HOLY SH*T” scenes in the middle that were unforgettable. I wish Will all the luck in the world because he’s an awesome contributor to the site. However, next time, I want that easy read from him! :)

Script link: Year of the Spy

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I wouldn’t intricately weave well-known music into a montage. By that I mean, you give us a few montage images, then a lyric from the song, then more montage images, then another lyric. Here’s why. While this stuff works GREAT on screen, it’s actually really hard to follow on the page. Often times, we don’t know the song as well as you do. So when you give us a lyric, we have to stop, sing the song in our head, get to that lyric to know what we’re listening to, and then get back to the montage, which is already a disjointed experience, considering we’re jumping to different moments in time. And, on top of that, they never get the song you want anyway. They always have to pay for something cheaper. So I would leave that part up to the filmmakers and just make your script as easy to read as possible.