It’s a wonderful and rare day here on Scriptshadow. We get to celebrate one of the very few IMPRESSIVE amateur scripts I’ve read for the site. Grab your popcorn and notepad. This should be fun!

Genre: Crime/Drama

Logline: A mob rib breaker turned high school janitor seeks to redeem his violent past by preventing a young girl from making the same mistakes he did, but when drugs and gangs overrun her school, he must risk his cover to clean it up.

Why You Should Read: Writing is the reason I get up in the morning. I have been a Nicholl Fellowship quarterfinalist multiple times, a Page semi-finalist and was the 2016 winner of Screamfest with my screenplay “Plum Island”. My day job working with troubled youths allows a consistent reservoir of unique experiences that I draw upon when creating realistic and fleshed out characters. Why read? “The Janitor” perfectly portrays human complexities in a gritty urban setting and creates cinematic characters that are both mythic and believable.

Writer: Matthew Lee Blackburn

Details: 113 pages

If you’ve been away from Scriptshadow for a few days, you missed that Friday I read a killer amateur script. It’s so rare that we get a great amateur screenplay, I didn’t want to rush a review out. I wanted to take my time, think about the script, then do it justice. Hence why you’re getting the review today.

The biggest surprise about The Janitor is that I’d almost given up on it by page 10. The script started out in a clunky manner, and since past experience tells me these scripts don’t get better as they go on, my mind began powering down. I was still going to read the script. But I wasn’t going to be 100% present.

And then something magical happened. We did a little time jump, began a new storyline, and introduced some of the most realistic characters and situations I’ve encountered in a screenplay all year. Another reminder that it’s possible to turn any reader around, no matter how tired or distracted they are, if you write a great script! Let’s take a look!

Despite his boss’s assumptions, Marty isn’t about to rejoin the criminal life that put him behind bars in the first place. Therefore, when he gets out, the first thing he does is steal a chunk of his boss’s money, buys a new identity, and disappears into rural America, where he eventually finds a janitorial job at Redimere Days, a high school that’s been racked by gangs and drugs.

After living with her grandmother for years, 14 year old Juliet Lloyd’s been sent back to her junkie mom and abusive stepdad’s house, where every day is an assault obstacle course. Her only escape is the 7 hours a day she spends at Redimere High. But as a new student who doesn’t know anyone, even that’s a rough experience.

So it’s nice when one of the popular kids, 18 year-old drug-dealer Mickey Kerr, takes an active interest in her. It’s clear to us that Kerr’s a no-good piece of shit. But with no positive life references, Juliet ends up trusting him. That trust nearly gets her raped by Kerr’s friends at a party. So the next day at school, Juliet beats the shit out of him in front of everyone.

The event puts her in line to be expelled, a decision Ruth, Juliet’s teacher and lone champion, begs the principal to reconsider. A compromise is made. Juliet can remain at school if she does a work study with the understaffed janitor, our friend Marty. Marty, the only person at this school who wants to be left alone more than Juliet, resists, but in the end, both must accept the arrangement.

You wouldn’t think that Juliet would enjoy cleaning toilets, but Marty is so kind, so helpful, that he quickly becomes the only person on the planet she can trust. When Marty learns that Juliet is getting beat up at home, he drives over to her house and frightens her stepdad so bad he pisses himself. Just as it’s looking up for Juliet and Marty, Marty’s old criminal gang finds out where he’s run off to. They show up in town with a simple goal: make Marty pay for ever thinking he could steal their money.

I’m sure a lot of you are asking the question: Why did Carson respond so well to this script as opposed to mine? What is this writer doing that I’m not? One of the things I’m constantly looking for in a screenplay is authenticity. Does what’s happening on the page feel like it represents real life? Or is it a facsimile of real life, a writer’s attempt to conjure up a reality he knows nothing about? 9 times out of 10, it’s the latter. Most writers are throwing characters and sequences on the page that are carbon copies of their favorite movies. They’re not digging into their own lives and giving us their own reality.

What I loved so much about The Janitor is that it feels like real life. For example, in a lot of screenplays, when there’s a kid who’s getting abused, writers will play it safe. Wherever there’s an abusive parent, they’re countered with a protective parent. That’s a very “movie-like” thing to do. You’re considering how the audience is going to respond. You’re considering the resistance producers might have to a 14 year old girl getting abused so intensely. So you wrap things in a buffer, a Hollywood safety net that lets everyone know: “It’s okay, everybody. This is just a movie.”

The Janitor doesn’t do that. The step-dad is an abusive lunatic. But the mom is just as bad. She doesn’t give a shit about Juliet. She’s high all the time. She screams at her nonstop. If the stepdad is swinging the bat, the mom’s placing the ball on the Tee. It was that setup that let me know, this world isn’t “Hollywood safe.” This is the real world, where sometimes people are placed in terrible situations where there are no lifeboats.

And Matthew, the writer, never shies away from this reality. There’s a scene in the script where the dad and Juliet are in his car and he’s mad at her and he just mashes her face into the window. It’s raw and unfiltered and real. And that’s what makes it resonate. But normally, I’d see this scene played safe. The stepdad might verbally abuse her instead. Or the violence might be off-screen. And I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with those choices. But the reason The Janitor works where so many other scripts don’t, is that it’s never afraid to be real. It’s not trying to hide anything.

A great side effect of authenticity is that it does wonders for your dialogue. If you’re mining the reality of a situation as opposed to making it up, characters talk more like real people. They’re more passionate, thoughtful, raw, unfiltered, genuine. And the great thing is, is that a lot of this dialogue writes itself. Remember, you only struggle to come up with words for your characters if you’re trying to artificially force words into their mouths. If you just let them speak, they’ll speak truthfully.

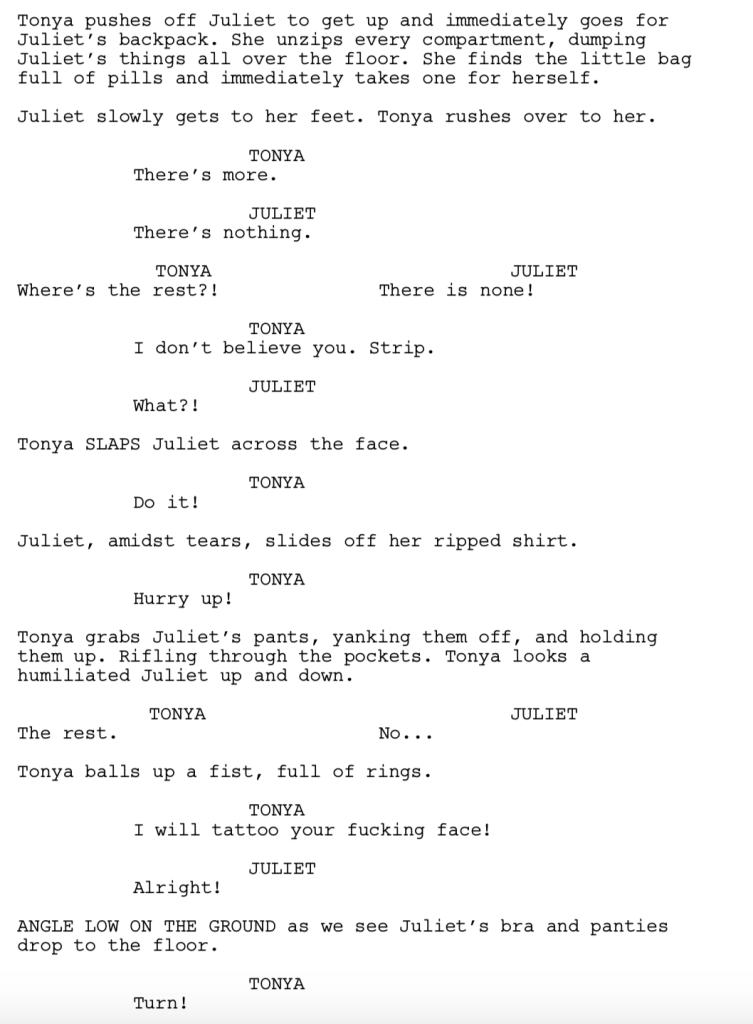

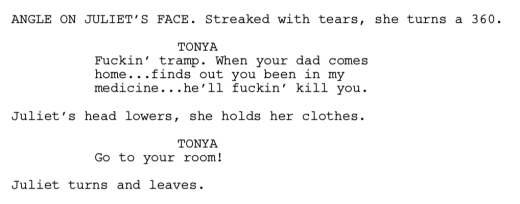

In this scene where Juliet’s mom accuses her of stealing her pills, you’ll see that there are no flourishes to anything anybody’s saying. It’s just one person wanting something and another person resisting. And when you have that, there are no long discussions. It’s a series of brutal clipped statements.

And this scene represents just how unflinching this script is. Juliet is living in a hellhole and we’re never given a break from that. We experience things as she experiences them. She gets attacked at school and needs to regroup? Tough cookies. She comes home and has to deal with her meth-head mom.

Now if you’ve been reading my site for awhile, you know the effect this has on the audience. Readers will always root for characters who are being harmed or taken advantage of. For that reason, we fall in love with Juliet immediately. We want to see her get out of this mess. It’s the driving force for why we must read til the end. To see that she escapes this hell on earth.

One of the tougher challenges with a script like this is finding a way to frame the plot. This isn’t a traditional goal-driven story. Sure, Juliet has to complete her work-study with Marty in order to remain at school, but that’s hardly a plot worth building a script around. So Matthew does something really clever. He creates this looming confrontation. We know that those guys from the beginning are coming back. You don’t get to steal a bag of money from a crime boss and not have to deal with it. So the fact that we know Marty’s going to have to fight off those guys at some point provides the script with a stealthy plot frame.

Remember, as long as we feel like we’re moving towards something big in a story, we’re engaged. GSU may be the easiest model to use. But it’s not the only model out there. It can be argued that The Janitor’s plot is a series of looming confrontations.

Speaking of the opening, that’s the only thing here Matthew has to fix. I noticed a few of you mention he should ditch the opening. But without the opening, we don’t have that looming threat anymore. So the opening needs to stay. But it has to be simpler. The problem is that a man we have no reference for is speaking in voice over. Three characters are introduced quickly afterwards. Everyone’s referring to backstory that we don’t understand. It’s no wonder we’re confused.

In these cases, I always tell the writer: What are the key pieces of information you’re trying to convey? Focus on those things and strip away everything else. All we need to know is that Marty just got out of prison, he used to work for these guys, he wants out, and he sees a way out with the money. Build a scene around that and strip away all the confusion.

But outside of that, I thought this script was spectacular. One of the best amateur scripts I’ve ever read on this site. It bumped right up against my Top 25, almost squeezing in. It very well may get there in the future. I’m going to be talking to Matthew tomorrow and I hope to help him take the next step in his writing career because he deserves it with this script.

Script link: The Janitor

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The earlier in the script you are, the more hand-holding you have to do. The Janitor’s only slip up is this opening, where four characters we don’t know and who have a complicated backstory, are thrown at us in the middle of a murder. Something this complicated can’t be rushed through. You need to slow down and hold our hand more, walk us through it so we know what’s going on.

What I learned 2: You don’t have to hold our hand if you simplify the situation in the first place. I just want you guys to know that the simplifying option is always out there. If you’re having trouble explaining an intricate situation to the audience, such as this one, the solution might be to strip out the extraneous elements in order to make everything easier to explain.

What I learned 3: It’s important to note the marketing angle to this idea. The crime aspect. Without it, this is a straight drama, and therefore way more difficult to market. The crime angle makes this a movie as opposed to a screenplay.