So in the last two weeks since I wrote the GSU article, I’ve been asked a lot of questions about movies that ignore some, or in a few cases, all of the GSU variables and still manage to work. The truth is, goals stakes and urgency aren’t the only way to keep your audience interested. They’re just the most effective way. But because the other methods for keeping a story interesting are more intricate and difficult to apply, they require more skill and experience to pull off. Now in the past, I’ve merely alluded to these options like a magical potion you needed to attend Hogwarts to get a hold of. But today I’m going to get into a few of these subtleties by breaking down the most important element of GSU – the goal.

Everything starts with the goal. The stronger and more clear your goal is, the more drive and purpose your story will have. Get the Ark (Raiders). Find the treasure (Goonies). Win the fight (Rocky). How much simpler and easier is it to understand than that? However, there are different kinds of goals you can use to drive your story. None of these goals are going to give your story the same horsepower that that giant tangible goal will give you. But they can still work under the right circumstances. Let’s go over each of these goals and then look at some movies that utilize them.

CHANGING GOALS

It is perfectly okay for goals to change during the course of the movie. Things happen that change the circumstances for the characters all the time. It makes sense then that what the characters are going after would change as well. If you look at Star Wars, the original goal is to get the secret Death Star plans to Princess Leia’s home planet. But when they get to the planet, it’s no longer there, and they’re captured by the Empire. Therefore, the goal has changed. They must now escape the Death Star (after saving Princess Leia of course). Once they finally get to the Rebel Base, an entirely new goal presents itself – destroy the Death Star. So it’s completely okay to change goals over the course of the story. Just make sure that each goal is powerful.

A MYSTERY

Some movies are structured so that we don’t know the goal yet. Instead, a mystery is what drives the story. Assuming that this mystery is intriguing and that we want to know more about it, you technically don’t need a goal. This is how The Matrix is structured. The first 45 min. of the movie is designed as a mystery – What is the matrix? Because they did such a good job making that mystery compelling (we see normal people defying physics), we stick around to learn what it’s about. Once we do find out, the movie switches to a series of goals. Learn how to use your new powers. Go see the Oracle. And eventually, save Morpheus. But it all started with a mystery.

THE THROWAWAY GOAL

The throwaway goal is a goal a lot of indie movie writers use to give their stories a bare-bones narrative, even though the goal itself isn’t that important. This is a dangerous goal because it’s not a very active one. Sideways is a good example of a throwaway goal. Paul Giamatti’s friend claims that his goal on this trip is to get Paul laid. But in reality, that’s not really that important. What’s important is the development of these characters over the course of their journey. It is very rare that a throwaway goal screenplay will be purchased on spec. These movies just don’t have enough horsepower for studios to take a chance on them. Most of the time, these movies will come from writer-directors who are able to bypass the spec purchase stage and make the movies themselves.

SOMEONE BESIDES YOUR MAIN CHARACTER HAS THE GOAL

Now you’re moving into tricky territory because preferably, you want your main character having the central goal that drives the story. But there are instances where you don’t need this as long as *someone* has the goal. So in Good Will Hunting, it’s Prof. Lambeau who has the main goal. He’s trying to train Will so he can reach his potential. The biggest problem you run into with this approach is that your main character ends up becoming too reactive, or worse, inactive, and will therefore come off as boring. Good Will Hunting is one of the few movies where I’ve seen this work so I would be weary of using it yourself.

OPEN ENDED GOAL

The open ended goal is a goal without a clear end point. This goal is never as powerful as a tangible goal because the finish line is murky. Audiences like people who have clear and easy to understand motivations because it’s easier to understand what’s going on. However, this goal has been shown to be effective under the right circumstances. In Jerry Maguire, Jerry McGuire doesn’t really have a goal other than “to get back on his feet” or “to put his new business on solid ground.” (You may be able to make the argument that Rod Tidwell has the goal that drives the story – to get a new contract – but let’s not confuse ourselves). This type of goal still works mainly because it forces your character to be active. Because your character is still going after something, he’s constantly out there doing things and pushing the story forward.

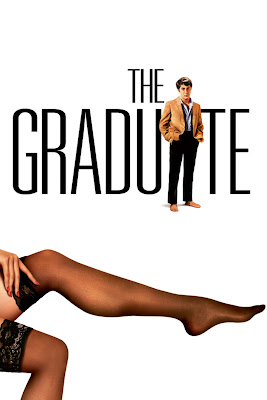

THE NEGATIVE GOAL

The negative goal is when your character is trying not to do something. In my eyes, this is one of the most dangerous goals to give a character because it sets up a movie that does the exact opposite of what movies are good at doing, which is telling stories about people going after things. The most famous example of this is, of course, The Graduate. In that movie, Dustin Hoffman’s goal is to *not* make a decision. For this reason, Dustin is mainly reacting to everything around him, meaning everything is shining except for the main character, which modern audiences just have a really tough time accepting. Either way, in a story where there is a negative goal, eventually a positive goal needs to emerge. At a certain point, Dustin Hoffman’s goal becomes to get Mrs. Robinson’s daughter.

THE HIDDEN GOAL

Probably the most difficult goal to pull off is the hidden goal. This is a goal our main character has but we don’t know that he has it until the end of the movie. The reason this is so hard to pull off is because for 95% of the movie, the character appears to us to be inactive, which in most cases is boring. The most famous example of this is The Shawshank Redemption. For all we know, Andy Dufrene is just hanging out in jail trying to live his life. What we find out in the end though, is that everything he did was a plan to get him out of here and therefore a part of an extremely strong goal. While this situation tends to create a great ending (because of the surprise factor), it means you have to use a variety of subtle and less dominant storytelling techniques to make the other 95% of your screenplay work, which is really hard. If you plan to use this technique, I wish you luck, because it ain’t easy.

THE QUESTION

A close cousin to the mystery is the question – which is basically a central question that drives the story. The place where you’re going to find this the most is in romantic comedies, where neither character may have a clear goal, but the question of “will these two get together?” drives our interest. The most important thing to remember when applying a question instead of a goal, is that your character work has to be impeccable. And if it’s a romance, we have to like your characters (or at least be highly intrigued by them) and we have to want them to be together. If we don’t have that, then we don’t care about the answer to the question. It’s also a good idea to add some sort of work goal or subplot goal to add some drive to your story in these types of movies. If all that’s driving your story is a question, your audience might get bored quickly.

Now let’s look at a few random movies that don’t have the traditional dominant goal, and see which of these options they used and how they integrated them.

BEFORE SUNRISE – Like a lot of romantic movies, what’s driving the story here is a question – will these two people end up together? Or, if you want to get more specific, what’s going to happen when the night is over? Linkletter did a great job creating a really tight time frame so that the script had urgency. Even though the conversations themselves were somewhat mundane, because the end of the night was always so near, each of these conversations is interesting in a way they wouldn’t have been had the time frame been spread out over two weeks.

SWINGERS – Swingers is one of the trickier narratives you’ll see in a screenplay. For a lot of reasons, it shouldn’t have worked. It’s basically driven by the open ended goal of Mikey trying to get over his girlfriend. The reason it’s tricky is because Mikey isn’t actively trying to get over her. It’s Trent who wants Mikey to get over his girlfriend so he can have his friend back. That’s why they go to Vegas. That’s why they go out all the time. That means you not only have an open-ended goal, but a secondary character who has the main goal. What’s important to remember is that even though both goals are relatively weak in comparison to what normally drives movies, Trent’s goal forces the characters to get out there to do things and be active. As long as your characters are doing things, your story is going to have drive.

FERRIS BUELLER’S DAY OFF – Ferris Bueller is one of the few successful movies that uses a negative goal. The goal here is to not get caught. Now if you wanted to, you might be able to switch this goal around and say it’s for this trio to try and make it through the day. But since they’re constantly being chased and constantly avoiding others, what’s driving the story is mainly the goal of not getting caught.

THE SIXTH SENSE – The Sixth Sense uses three methods to drive its story. The first is an open ended goal. Bruce Willis’s goal is to help this kid. Since we don’t know what constitutes the endpoint of that goal, that’s why it’s considered open ended. The second is a mystery. There’s something wrong with this kid and we want to know what it is. Once we do find out what it is, a set of changing goals (to help each of the ghosts) finishes up the story.

ROSEMARY’S BABY – Another tricky screenplay to break down in that it doesn’t have any clear objectives for its main character. I would probably categorize Rosemary’s Baby as a negative goal in that the main character is simply trying to make sure nothing happens to her baby. Now like I mentioned above, whenever you have a negative goal, you eventually want your character to have an active goal. That’s what happens here when Rosemary starts suspecting something is wrong. She begins investigating the people she’s dealing with, looking into the possibility that they’re a cult.

The thing you have to remember with screenplays is that each story is unique and no storytelling technique is set in stone. You have to adapt sometimes. You have to improvise. And don’t forget that some of what drives these stories is open to interpretation. I’m not claiming that my examples are perfect. But they should give you a better idea of the different kinds of options you have when constructing your story. The idea is to get to a point where you can start using all of these options interchangeably and when needed, sometimes three or four times in the same screenplay, kind of like what The Sixth Sense did. But it takes time and it takes effort and it takes lots of practice to learn to use all of them. So get out there, keep writing, and keep improving. Good luck!