Oh MAN! What a tease. Today I was supposed to review 300 Years. However, I’ve been receiving some predictable backlash for doing so, with people claiming that I’m stacking the deck and trying to get it onto the Black List with a glowing review. And that I can’t be objective since I’m a producer on it, even though the reason I became a producer on it was that I read it and loved it. Anyway, I’m going to postpone the review until the new year, some time after the Black List is released, and we’ll travel 300 Years into the future then. Feel free to still discuss it in the comments, since I know a lot of you have read it, and I’ll join in when I can.

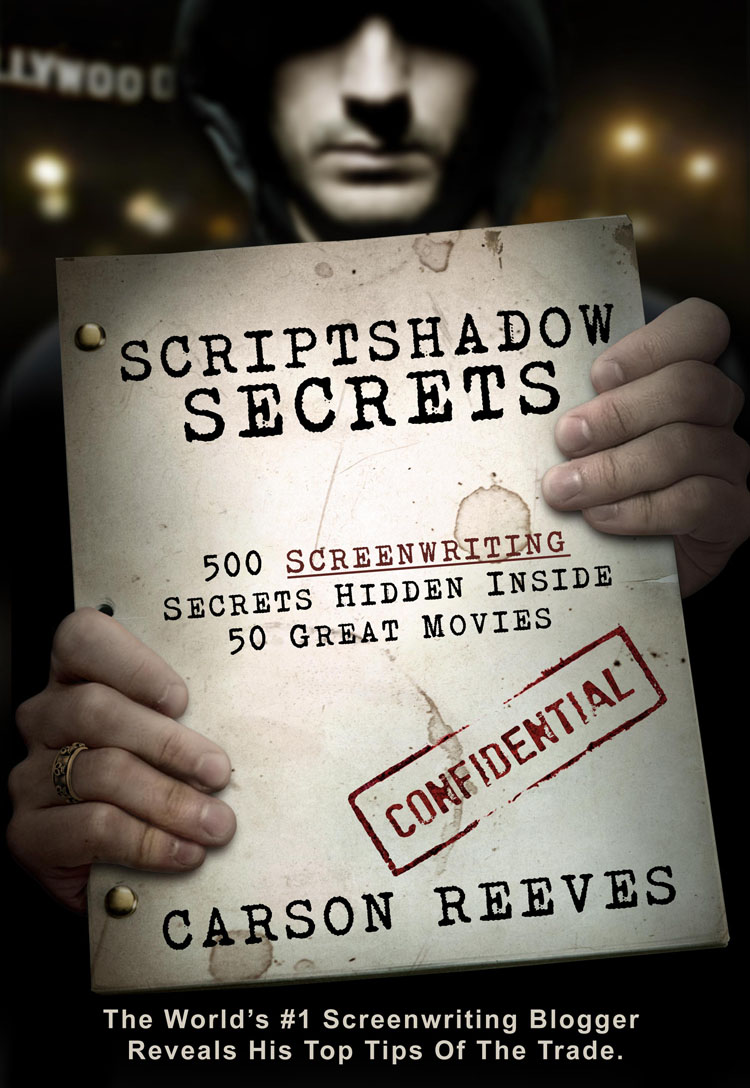

The good news is, I’m posting MORE GREAT ADVICE with another chapter from the book. Yesterday I gave you tips from “Pirates of the Caribbean.” Today, I’m giving you a screenwriting Academy award winner with the Coen Brothers’ “Fargo,” one of the best written scripts of all time. What I liked about this script was that it bucked a lot of conventional rules and still worked. As I discuss in the book, you need to break a few rules in every script you write in order to make it stand out. If you like this breakdown, remember there are FORTY-NINE other movies broken down just like this one. And while it’s only available in e-book at the moment, you can download the free “Kindle App” here so you can read it right from your computer – no Kindle or Ipad required! So, read today’s excerpt and then go buy the book!

Excerpt from Scriptshadow Secrets…

FARGO

Written by: Joel and Ethan Cohen

Premise: When a sleazy car salesman has his own wife kidnapped in order to extort her rich father, the plan backfires in every way possible.

About: Fargo is allegedly based on a true story. When you base your screenplay on a true story (or make that claim), you have what I call the “this really happened” advantage. If you go off on a random tangent, the audience goes with you. If something’s too coincidental, the audience still goes with you. They assume that no matter how unconventional or unstructured the story, it’s okay because “this is how it really happened.” Try to pull the same thing off in a fictional piece and audiences start crying foul because, “it would never happen that way in real life!” It’s a strange dichotomy, but true. I think that’s why Fargo is such an interesting screenplay. It makes some really strange choices (our protagonist, Marge, doesn’t arrive until page 30!) and yet you just kind of go with it because “that’s how it really happened.” Despite these weird choices, there are still LOTS of nuts and bolts storytelling lessons to learn from this Oscar-winning script. The Coens may be nuts, but boy do they know how to write!

TIP 179 – POWER TIP – Desperate characters are always fascinating because desperate people HAVE TO ACT. They HAVE TO DO SOMETHING. If they stand still, they’re dead. Jerry Lundegaard is in so much debt, has stolen so many cars, owes so much money, that he HAS TO ACT. And that desperation is what leads to every cool moment in the film. Nothing can happen without Jerry’s desperation. So if you want excitement, make your character desperate.

TIP 180 – URGENCY ALERT – Here, the urgency comes from Marge investigating the case. She’s closing in on Jerry, which squeezes him into accelerating the plan. The Coens use people chasing their protagonists in almost all of their movies, which is why their movies always seem to move so well.

TIP 181 – For some great conflict, place your characters in an environment that is their opposite – So, if you’ve written a vegetarian character, you don’t want her big scene to happen at Vegan Hut. You want it to happen at a butcher shop! Conflict emerges naturally from these scenarios. In Fargo’s opening scene, the buttoned up Jerry Lundegaard walks into a seedy dive bar. It’s the last place he’d go, which is why it’s a perfect place to put him.

TIP 182 – The Pre-Agitator – A great way to ignite a scene is to inject it with conflict before it starts. So in the opening scene of Fargo, Jerry meets with Carl and Gaear to discuss the details of kidnapping his wife. Before Jerry can say a word, Carl points out that he was supposed to be here at “seven-fucking-thirty.” No, Jerry insists, Shep set it up for “eight-thirty.” Carl shoots back that they were told seven-thirty. Before we’ve even gotten to the meeting, there’s a cloud of conflict and frustration in the air due to our bad guys having had to wait an hour. Had the scene not begun with this misunderstanding, it wouldn’t have been nearly as good.

TIP 183 – DRAMATIC IRONY ALERT – In the above scene, we learn that Jerry’s going to have his wife kidnapped and demand ransom from her father. Note the scene that follows. Jerry gets home to find both his wife and her father there, the very people he’s deceiving. What would’ve been an average dinner scene becomes thick with subtext because WE KNOW (dramatic irony) what Jerry’s planning to do to these two.

TIP 184 – CONFLICT ALERT – The relationships in this movie are packed with conflict. Jerry isn’t close with his wife. Jerry’s son doesn’t respect Jerry. Jerry’s father-in-law doesn’t like Jerry. Jerry doesn’t like him either. Carl (Steve Buschemi) doesn’t like his partner. Gaear doesn’t like him either. Even the lesser relationships have conflict, such as Shep not liking Jerry or Jerry getting into it with customers. The only one who doesn’t have any conflict in her life is Marge, which is probably why she comes off as such a hero.

TIP 185 – SCENE-AGITATOR – When Jerry comes in to his father-in-law’s office to pitch his parking lot plan, the father-in-law and his right-hand man have set up the office so that there’s nowhere for Jerry to sit during the meeting. This forces Jerry to squat awkwardly on a sideways chair, throwing off his game just enough to affect his pitch. A small but brilliant scene-agitator!

TIP 186 – What would the Coens do? – If you have a scene or section of your script that feels boring, I’m going to give you a great tip. Ask yourself, “What would the Coens do?” The Coens rarely make an obvious choice. They treat clichés like cancer, and so should you. Let me give you an example: after Jerry comes home and “learns” his wife has been kidnapped, he calls his father-in-law to tell him. I want you to think about how you’d write this scene. I’ll give you a second. Finished? Okay, here’s why the Coens are different: We’re in another room, listening to Jerry call Wade (the father-in-law): “…Wade, it’s Jerry, I – We gotta talk, Wade, it’s terrible…” Then we inexplicably hear him start over again, “Yah, Wade, I – it’s Jerry, I…” It’s only once we dolly into the room that we realize Jerry is practicing. He hasn’t called Wade yet. At the end of the scene, Jerry picks up the phone, calls Wade, and we cut to black. We never hear the actual call. That’s a non-cliché scene if there ever was one and it’s the reason you need to start asking yourself this question when you run into trouble: “What would the Coens do?”

TIP 187 – Hit your hero from all sides – The more directions you attack your hero from, the more entertaining his journey will be. Take note of all the sides pushing in on Jerry here. The father-in-law wants in on the negotiations with the kidnappers (who can’t be involved because Jerry’s lied to them about the amount of money he’s demanding). The kidnappers themselves are demanding more money. The car manufacturer is demanding VIN numbers on the cars Jerry’s illegally sold. Marge is bugging Jerry about missing cars on his lot. When you bombard your character from all sides, you create LOTS OF DRAMA. And when you have lots of drama, scenes tend to write themselves.

TIP 188 – The most basic tool to make a scene interesting – The easiest way to make a scene interesting is to have two people want different things out of the scene. This creates conflict, which leads to drama, which leads to entertainment. In one of the more notorious (and talked about) scenes in Fargo, Marge meets up with her old high school friend, Mike Yanagita. In the scene, his goal is to hook up with Marge. Marge’s goal, on the other hand, is to reconnect with an old friend. This is why, even though the scene is arguably the least important in the film, it’s still entertaining, because both people in the scene want something completely different.