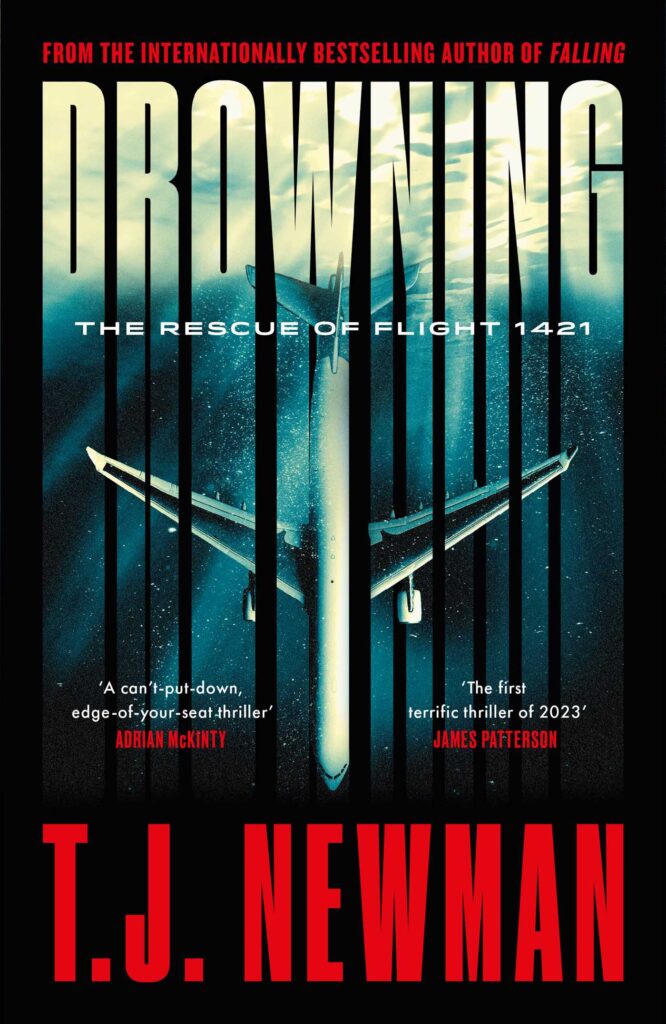

The big million-dollar sale from the flight attendant turned writer who’s become one of the hottest new names in Hollywood.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: Passengers must hope for a 1 in a million rescue after their plane crashes in the ocean and sinks, settling on an underwater cliff.

About: A couple of years ago I reviewed T.J. Newman’s first plane book, Falling, which also sold for a million bucks to Hollywood. Newman didn’t take long to capitalize on her buzz. Selling two books is always better than selling one. And staying in her lane was smart. If she would’ve tried to write a romance novel, she would’ve heard a lot of crickets. More planes, more dolla bills!

Writer: T.J. Newman

Details: 280 pages

I’m a T.J. Newman, the person, fan. This is a woman who spent 20 years trying to break into Hollywood. She got rejected by every publisher you can name. She represents resilience and persistence, two of the most critical qualities a writer must possess if he/she wants to succeed.

Those qualities can not be underestimated. Everyone talks about the sexy stuff that a writer needs. They need “voice.” They need to have their pulse on the people, knowing what concepts sell. They need to be a whiz with dialogue and plot and structure and pacing.

And you do need all those things.

But they mean nothing if you’re not resilient to rejection. LOTS of rejection. And if you’re not persistent. You gotta be able to keep trying. Not let the many negatives that come with the pursuit of art get you down.

Now, do I like T.J. Newman, the writer? That’s a more complex question. I thought her first book was okay but straightforward. It didn’t surprise me enough. I’m someone who needs a script to give me what the concept promised but also keep me on my toes. Let’s see how Newman did in those departments.

Engineer Will and his daughter, Shannon, are flying from Hawaii to the mainland where he’ll drop her off and then head back home. Unfortunately, Will doesn’t have a home to head to because he and his wife, Chris, an underwater construction director, are separated.

Will’s plane starts losing altitude just several minutes after takeoff due to an engine blowing up. Not long after that, the plane is in the ocean. The pilot, Kit, was successfully able to pull a Sully. But unlike the Miracle on the Hudson, the fiery engine is causing all sorts of issues outside the plane.

When everyone tries to head out to the water, it’s Will who screams at them to close the door. The fire is about to get a lot worse and anyone who’s out on the water will get roasted. He somehow manages to convince Kit of this theory and she closes the door.

Not long after that, the plane sinks to a little cliff a thousand feet underwater. Without getting too complicated, the plane is tilting over the cliff and slowly taking in water within its cracks. Will estimates they have about six hours of oxygen.

Cut to topside where Chris, Will’s wife, who’s currently on a job, hears about what happened and rushes over to join the Navy and help out with the rescue. The Navy wants to pull the thing up to the surface by its tail. But both Chris and Will use science to explain how that dumb plan will actually kill everyone.

Chris has a better plan that involves a slick rescue vehicle. Only problem is that the vehicle is broken. So she’s going to have modify the rescue and pull off a miracle. Will she do it all before the dozen people in that plane run out of air? Tick-tock-tick-tock-tick-tock.

If you want to write a book – or a script – that sells for a million dollars, you can’t go wrong with a big flashy situation and an ultra-tight timeframe.

I don’t think the average writer realizes just how powerful timeframes can be in storytelling. If you tie a 6 hour timeframe to a life-or-death situation, it’s hard for a reader not to get pulled in by that.

This movie doesn’t play the same way, for example, if they’ve got a full day of air. I see this problem a lot. I just gave a note to a writer in a consultation who had a 90-day timeframe on their story. 90 days is a long time for anything! I suggested 1 month.

If the reader doesn’t feel the urgency of the situation, you’re missing out on a major dramatic anchor for your story.

So the setup here was good. I was pulled in.

And then the writer did something that nearly killed it for me. Yup, we’re talking about DKB (Dead Kid Backstory). I know some of you like it. You’re all wrong. I am here to tell you it is a failed dramatic device 99% of the time any writer tries to execute it. Are you really betting you’re that 1%?

Here, Chris, Will, and Shannon have a DKB. Their other daughter died in a pool accident six years ago. Look, it wasn’t the worst use of DKB I’ve seen. But the big reason DKB doesn’t work no matter how much you want it to is because it’s lazy. It’s the laziest form of emotional manipulation a writer can use. “Love my characters cause their child died!” It’s desperate.

And I know that it’s a lazy choice because it’s not even the only time Newman used it in this novel! There’s ANOTHER character with a DKB. Which tells me that the writer is only willing to pick the low-hanging fruit when it comes to her backstories.

So this put me back in a neutral place. Strong opening. Weak backstory. Back in the middle.

What you’ll hear most writing teachers say is that there’s the external story and then there’s the “real” story, which amounts to the human story at the center of your script/novel. The external story is a plane settling on the bottom of the ocean. But the real story is about this family reuniting.

The problem is I’m not sure whether Chris coming to save Will and the two having jobs that are perfectly suited to figuring out this problem is serendipitous or coincidental. One is good for storytelling. The other is bad. And it did feel a little too perfect for me. That this man’s wife just happens to be the only person in the world who knows how to save this plane.

But I get what Newman was doing. She didn’t want this to be a nuts and bolts rescue. She wanted an emotional core to the story. A family reuniting is, technically, the right approach to these things.

I’m just not sure I ever cared that much. That’s the problem with making lazy choices (DKB). They affect how much you care about the characters involved in that backstory. Cause you know you’re being aggressively manipulated. You can see what the writer is trying to do. And that’s when the suspension of disbelief breaks.

Also, there’s a difference between choosing sad backstories and choosing depressing backstories. A sad backstory is one where we can tell it hits the characters hard but we can still distance ourself from their experience. A depressing backstory feels lousy to everybody. You’re telling about dead kids? Why do I want to read about dead kids in a movie about a plane rescue? That’s just depressing s—t. I don’t read thrillers for that.

In case you hadn’t noticed, DEAD KID BACKSTORY BOTHERS ME.

Despite this, the story moves fast. And the scientific stuff seems surprisingly well-researched. It felt real. What TJ Newman did well is that she truly made you wonder how they were going to save these people. Cause there was no clear solution. Too many writers make it easy to figure out how they’re going to solve the big problem. I didn’t know here. And I liked that two of the plans failed, leaving them without any options left. NOW what are they going to do? I genuinely didn’t know.

So, much like her first book, I thought this was okay. It was like a less good version of Ron Howard’s Thai cave rescue film. But it’s also a much flashier concept than that. So it could end up being a good movie. And I will always champion when studios make an original film.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Here’s a dialogue trick. Let’s say you have to dish out some backstory about a character. The way you normally do this is to have a second character ask your character questions about themselves. Then our character answers them and, in the process, shares their backstory. The mistake writers make in these scenes is focusing on our character explaining his backstory. Writers do this to make sure that all the information about the character’s backstory gets to the reader. For that reason, these scenes never work. They’re written to a disembodied audience rather than someone in the story. To solve this, FOCUS MORE ON THE PERSON ASKING THE QUESTIONS. In other words, make them genuinely curious. Make them WANT THE ANSWERS. Cause if the person asking the question genuinely wants to know the answers, then our character will be speaking more to him than to the reader. And that’s how you write genuine backstory dialogue in that circumstance.