If I say to you the names Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely, I’m guessing a little over 25% of you know who those two are. If I say those two names on anything other than a screenwriting site, that number drops to .001%.

And yet, those two are the writers of, at one point, the highest grossing movie of all time, Avengers: Endgame.

I want you to think about that for a second. The writers of the most successful movie ever made are so obscure that the overwhelming majority of the people on this planet – people who have seen the movie mind you – have never heard of them.

And yet, if I say the names Quentin Tarantino, Aaron Sorkin, Diablo Cody, and Taylor Sheridan, peoples’ ears perk up. They know those names. Those are respected screenwriters.

This got me thinking about the differences between pursuing a studio career versus pursuing an artist’s career.

In one, you become a cog in the machine, moving from high-profile assignment to high-profile assignment. However, you are a very generously paid cog. And if you can make it to the top of the studio mountain, like McFeely and Markus, or Shay Hatten (John Wick sequels), you are drowning in cash money. Even if no one knows your name.

In the other, you are writing for the love of it, and are getting recognized as a respected name in the business. If you can crawl to the top of this pile, you are fighting for Academy awards. And the public may even know your name.

But while you might never be a cog, you will spend a lot more time fighting to get your projects made due to the fact that they’re not obvious money-makers. So while you gain prestige and respect within the industry, you lose financial security.

I think it’s important for amateur writers to figure out which direction they want to go in because each path requires a different strategy. And I want to discuss those strategies today.

If you want to become a studio screenwriter, you need to become obsessed with high-concept. That’s going to be your ticket to ride. Back in the day, you operated on a 1-step process whereby you wrote a high concept script to sell it.

These days, they’ve added a step. You write these scripts to get recognized as somebody who’s good at writing this kind of script. A manager or agent takes you on based on the strength of that spec. They send your script around town to the big-budget production houses and studios, and hopefully, one of those places hires you to write *their* big-budget script.

This is exactly what happened to Michael Waldron. He wrote a script called The Worst Guy Of All Time, and the Girl Who Came To Kill Him, which had time-travel, comedy, and acton set-pieces. That script eventually got to Kevin Feige and Feige loved it. Which led to Waldron getting hired to write Loki, and now the next big Avengers movie, Secret Wars.

Another thing studio writers must have is a mastery of structure. You have to know the three-act structure like the back of your hand. You have to understand page counts and on which pages key plot beats happen. You need to know terms like the “inciting incident” and the “Mid-Point Twist” or “Mid-Point Escalation.”

You need to know these things because studios are way more technical in how they approach things. They don’t leave anything up to wish-washinesss or “feel.” They need to be able to say to you, “the first half of your second act is 10 pages too long. Cut 10 pages out.” And you have to know what that means.

They’re going to use words like “pacing.” They’re going to say, “The pacing in your third act sucks.” And you need to know what that means and how to fix it (it basically means that your third act scenes are dragging or you’ve got some extra scenes in there that aren’t needed).

Studios don’t have time to teach screenwriters. They’re expecting you to already know the technical details like the back of your hand. I learned this the hard way. I recommended a couple of screenwriters who weren’t ready for the intensity of a studio assignment yet, and received a couple of frustrated phone calls from the producers regarding the writers’ abilities.

These writers had previously written strong scripts. But they were scripts where they didn’t have to answer to anyone. The studio system is a collaborative system. You need to be able to work with others. You need to be able to receive notes and understand what they mean.

Which is I why I remind writers if they’ve written ten scripts and still haven’t “made it” yet, that doesn’t mean they should give up. All the learning they’ve gone through writing those scripts has made them great candidates to become studio screenwriters. Cause they’re familiar with a lot of the speed bumps associated with screenwriting and know how to tackle those bumps.

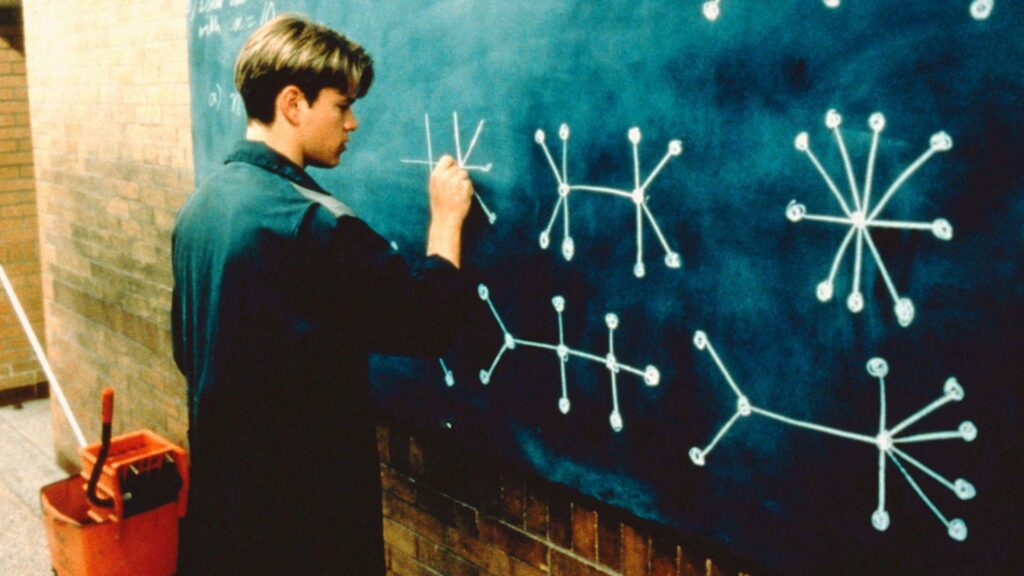

Meanwhile, if you want to become a respected screenwriter, aka an “artist,” high concept isn’t nearly as important. In fact, it might take away from the other aspects of your writing that you’re trying to showcase. You should still be seeking out a clever concept – something ironic maybe (Good Will Hunting – a Harvard janitor solves a math equation that nobody at Harvard could solve). But it doesn’t have to be a big flashy idea with a lot of kung-fu or time traveling going on.

What you *do* have to be great at is character development. If you don’t enjoy delving into the depths of people and what makes them tick, the “artist” route is not the route for you. It’s better to pursue the studio side. Cause studio screenwriters only have to know how to make their characters likable. They don’t have to write Oscar-worthy character journeys.

Character development boils down to creating imperfect characters who we still root for. Arthur Fleck from Joker is a good example. Or Louis Bloom from Nightcrawler. Or Cassandra from Promising Young Woman.

You need to know how to give these characters flaws (Cassandra could not see through her rage and let it dictate all her actions). You need to know how to explore those flaws. You need to know how to have your characters overcome those flaws at the end. Or fall victim to them if that’s the kind of movie you’re writing (like Cassandra). And you need to know how to do this with character relationships as well. You need to know how to start a relationship in one place (broken) and end it on the other end of the spectrum (fixed).

And you need to know how to make characters interesting. Not boring. The most respected screenwriters are the ones who can create classic characters. These screenwriters are obsessed with people and want to dig into them and know how they tick. That intense curiosity is what leads them to write these iconic characters.

You also need be great in one of two other areas. You need to be saying something important thematically with your script. Or you need to have a unique voice. These days, social issues are the easiest ways to explore a theme so they’re the perfect option if you want to go in the thematic direction.

If you’ve never been good with theme or you don’t have any interest in writing a script about 12 Native Americans who go to the moon, you need a flashy strong voice on the page. Taika Waititi. Emerald Fennell. Christy Hall. A voice that explodes and forces the reader to take notice.

Naturally, artists will be shooting at a different target. Instead of blanketing the town with a sexy action premise and hoping to get a meeting at 87North, you’ll be trying to make the Black List. If you can make the Black List, that’s going to give you the first bump you need towards becoming that “respected” screenwriter. It’s also going to put you in a great position to get your movie made.

I forgot what our last tally was, but I think it’s between 25-30% of Black List scripts get turned into movies. Which is great. Because one of the crappy things about being an artist is that it’s harder to get movies made since your script won’t have the same marketability as a high level, or even a low-level, studio release. So using the buzz of a Black List showing to get your script made is a legit strategy.

But the reality is that, as an artist, you’re going to have to do a lot more work than the studio writer types to break in because it’s always going to be harder to break in with unmarketable material. It’s just harder to get people to read things that don’t have a sexy premise. They’re always the last scripts I read and I think most people in town feel the same.

So as long as you know the journey will be longer and harder, you can accept the challenge and not get discouraged so easily.

Of course, there’s a third option – which is the TV option. But we’re out of time. Maybe that’s an article for a future date. Let me know if that interests you. In the meantime, figure out which kind of writer you are and start strategizing your career immediately!

Get A Screenplay Consultation with Carson! – Do you want me to look at your script? Tell you how it stacks up to the other 10,000 scripts I’ve read? How it stacks up to all the scripts being sent around town? Is it up to par with those scripts? Is it better than those scripts? Is it not as good? If so, what’s wrong? How can you fix it? This is my area of expertise so if you’ve been thinking about getting a consultation, now is the time to do it! I can give you $50 off if you mention this article. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com to get started!