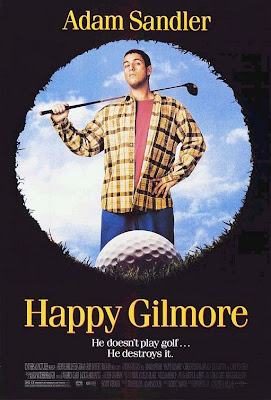

It’s Comedy Theme Week everyone. For a detailed rundown of what that means, head back to Monday’s post, where you’ll get a glimpse of our first review, Dumb and Dumber. Today, I’m taking on the best sports comedy ever made, Happy Gilmore.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A failed hockey player is forced to join the pro golf tour in order to save his grandmother’s home.

About: As not many people saw Adam Sandler as a movie star at the time, Happy Gilmore did only so-so at the box office, taking in 38 million dollars. The movie, however, would later become a huge hit on video and help propel Sandler into becoming one of the highest paid actors in the world. Roger Ebert said of Sandler’s performance at the time, which he did not like, that he “doesn’t have a pleasing personality: He seems angry even when he’s not supposed to be, and his habit of pounding everyone he dislikes is tiring in a PG-13 movie.” As I find Sander’s anger to not only be the funniest part of the film, but an integral part of his character and character arc (and thus organic to the story), it just goes to show how polarizing reactions to comedy can be!

Writers: Tim Herlihy and Adam Sandler

Leave it to Adam Sandler to restore some normalcy to the craft of screenwriting.

Uhhhhh….what?? Did I just mention Adam Sandler and screenwriting in the same sentence? And that sentence didn’t include the words “dreadful,” “incomprehensible,” “horrifying,” “unreadable,” or “brain-cancer-inducing?” I believe I did. Yes, believe it or not, before Sandler and his “writing team” began invading our cineplexes with movies like “Has-Beens Hanging Out At A Cabin” or whatever the hell that piece of crap was with him and Chris Rock and Kevin James, he actually made a few good movies. And Happy Gilmore, by a country mile, was the best of them.

While yesterday’s comedy made all sorts of funky structure-breaking choices that confused and confounded me, Happy Gilmore is one of the most straightforward by-the-book executions of the three-act structure there is. In fact, if I was going to recommend a template for the execution of the single protagonist comedy, I would put Liar Liar first and Happy Gilmore second. As shocking as it sounds, this screenplay is a thing of beauty.

As many of you know, Happy Gilmore is about a lousy hockey player with anger management issues who’s forced to become a professional golfer in order to save his grandmother’s house. Happy’s unique talent is his ability to drive the ball further than any professional golfer in the world. But after his success begins to draw the ire of tour hot shot and universal asshole Shooter McGavin, Happy finds himself not only struggling to win back his grandmother’s home, but trying to defeat the best golfer in the world.

What I love about Happy Gilmore is that it follows all the rules, yet still manages to feel fresh and funny. It starts by giving us a hero with a flaw. Happy has anger issues. This flaw, while admittedly simplistic, gives our character some depth, something to overcome during the course of his journey. And even better, in “proper” screenwriting fashion, we find out about this flaw not because our hero or some other character *tells* us he has anger issues. We find out through his *actions*. After not making the hockey team, Happy proceeds to beat the shit out of his coach.

This is followed by the inciting incident, the moment in the screenplay that incites a call to action. Happy’s grandmother loses her house because she didn’t pay her taxes. She owes $250,000 dollars and if she doesn’t come up with it within 90 days, the house will be sold off. So our character goal is set: Get $275,000 before the 90 days is up.

In order to beef up that goal, the writers make sure you know that the grandma is the nicest sweetest coolest most loving woman in the world. And because you love her, you want to see Happy get her house back for her. Also, remember how the other day I was talking about positive and negative stakes? How you want your character to not only GAIN something if he wins, but LOSE something if he loses? We have that here when we find out Grandma is staying at the nursing home equivalent of a concentration camp. If Happy gets the money, he gets her house back. If he loses, she’s stuck in this hellhole forever!

But here’s where the genius really kicks in. For most movies to work, your hero must DESPERATELY WANT TO ACHIEVE HIS GOAL. If your hero doesn’t want to achieve his goal, then what’s the point in watching? He doesn’t really care. So why should we? But if someone’s desperately going after a goal doing something they enjoy, where’s the fun in that? Especially in a comedy. It’s much more fun if they DON’T like what they’re doing. And Happy hates playing golf. So then how do you make someone despereately want to achieve something if they don’t like what they’re doing? Simple. You force them into it. So Happy hates golf, but he HAS to play it. And this conflict he has with the sport is what leads to the majority of the comedy in the movie. Again, CONFLICT BREEDS COMEDY. This is how we get Happy swearing up a storm as he tears up a pack of clubs on national TV while the Tour President tries to calm down the sponsors. Or how we get the classic comedy moment of Happy fighting Bob Barker. It’s the key component to the movie working, that Happy wants desperately to achieve his goal, but still hates what he’s doing.

One commonality we see between Happy Gilmore and Dumb and Dumber is that the writers work really hard to make sure you love the main character. We start out with Happy’s voice over. Voice overs always get you into the head of your hero, breaking that fourth wall and making you feel like you know them. So it’s a great device to create sympathy (though still dangerous!). Through it, we find out that Happy lost his father when he was young (sympathy). Happy doesn’t make the hockey team (more sympathy). Happy gets dumped by his girlfriend (more sympathy). Happy employs a homeless man as his caddy (more sympathy). But what you may not have picked up on, is that there’s a very subtle twist to all of these sympathetic moments to draw our attention away from the fact that the writers are pining for our sympathy. Each moment is cloaked inside comedy. In other words, because we’re laughing, we forget that the writers are blatantly manipulating us. When Happy gets kicked off the team, he hilariously beats the shit out of the coach. When his girlfriend leaves him, he screams at her through the intercom (she eventually leaves and Happy is talking to a young boy and an aging Chinese maid). It’s very cleverly disguised inside comedy, and a neat trick to use in your own comedies.

Another great touch is that Happy Gilmore constructs the perfect villain: Shooter McGavin. A lot of writers think you just throw an asshole into the mix and that’ll be enough. Crafting a villain, even in a simple comedy, requires a lot of work. You have to give us someone we hate, but not in that obvious cliché stereotyped way. The mix here of arrogance, passive-aggressiveness, fakeness, and elitism, along with all those annoying little traits (his little “shooting of the guns” and recycled jokes) makes Shooter just a little bit different from the other villains you’ve seen in comedies.

Even the love interest is perfectly executed here. Usually, the love interest in a non-romantic comedy is unnaturally wedged into the story to appease producers. Here, it feels organic to the story. The romantic lead (who’s Claire from Modern Family btw) is the public relations director of the tour. So when one of the tour players is acting up (in this case, Happy Gilmore), it’s only natural that she be brought in to keep him in check. This stuff sounds like it just happens. But you gotta be on your game to make it feel natural. And you have to admit, you never question it in Happy Gilmore.

Chubbs (the one-armed golf pro) is also organically integrated into the script. Whenever you write a sports comedy, you want to not only have an internal flaw (anger, in this case) that the hero battles, but an external one as well, so there’s something physical they have to fix in order to achieve their goal. Here, it’s Happy’s putting. That’s what’s preventing him from beating Shooter. This is the reason Chubbs becomes essential. He has to teach Happy how to putt. Again, it seems obvious, but that’s because it’s so well done.

Another key that makes Happy Gilmore work – and a requirement for any good comedy – is that it exploits its premise. Whenever you come up with a comedy idea, you want to make sure you have 3 or 4 scenes that showcase that idea. That’s why the Bob Barker fight is genius. That’s why Chubbs taking Happy to the miniature golf course and Happy getting in a fight with the laughing clown is genius. These are the moments that represent the audience’s expectations of the idea. If you’re not including these scenes, you might as well not write the movie.

Happy Gilmore is also an incredibly tight script. That was another reason Dumb and Dumber threw me for a loop. It’s over 2 hours long. Most comedies need to be short. You’re making people laugh. Not giving them a history lesson. So by making Happy Gilmore a lean 93 minutes long, it forces the writer to make every scene count. And indeed, every single scene here pushes the story forward. Even the most questionable story-related scene, the pro-am tournament with Bob Barker, sets up Shooter’s goon/cronie who later tries to take down Happy in the Tour Championships.

This is by far the best sports comedy ever made. And just as a straight comedy, it’s pretty high up there as well. If you’re writing a comedy with a single protagonist trying to obtain a goal (like most comedies), you definitely want to study the structure of Happy Gilmore. It’s pretty much perfect.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Look to make your villain unique through a combination of traits. Shooter McGavin is clever (sending Happy to the 9th tee at nine), passive aggressive (offering backhanded compliments whenever asked about Happy’s talent), cowardly (backing away from a fight) phony (pretending to care about his fans when all he cares about is himself). This combination of qualities gives him a depth that you don’t often see in comedic villains. Making your villain a straight-forward asshole may get the job done, but layering him with numerous quirks and traits will separate him from all the cliché villains of the past.