DIALOGUE WEEK IS HERE! – All this week, I’ll be breaking down dialogue scenes from movies you love. Yesterday’s Dialogue Post is here.

I picked this scene not only because this is a great movie. But in interviews with Emily and Kumail, they’re open about the fact that this is their first screenplay. They didn’t even know what they were doing. Now there’s a caveat to this. They had Judd Apatow giving them notes for three years. But they’re still newbies, and this scene is a good representation of a newbie scene mistake that was saved by strong dialogue. The scene takes place after they’ve had sex for the first time (not in the supermarket, in case you thought the above picture was relevant). Let’s read the scene and break down why it works.

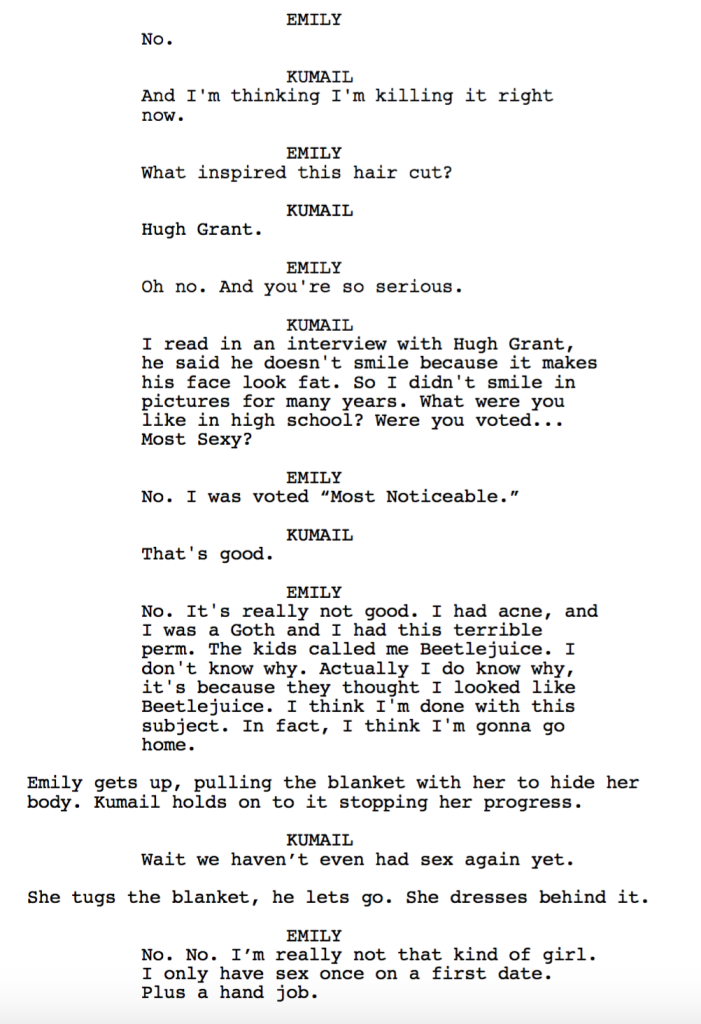

The reason this scene is interesting is because it comes on the back end of them having sex for the first time. This is relevant info to newbie screenwriters because dialogue between your romantic leads is always more interesting BEFORE they’ve had sex. Pre-sex scenes allow you to play with sexual tension. And sexual tension can do wonders for dialogue. I’m not saying it’s impossible to write good dialogue right after characters have sex. If there’s ample conflict, such as one character immediately regretting it, there’s great dialogue to be had. But characters sitting around chatting after sex? That’s potentially a boring scene.

Another problem here is that there’s no want. That was my big pitch Thursday. That the best dialogue scenes tend to have one character who wants something and another character who resists. We come into this scene with no ulterior motives. The characters are honest, open, and just want to chat. Dialogue rarely works when you do this. Without want or resistance, there’s no base conflict. Which means you have to find conflict somewhere else. And like I said, they’ve already had sex. So there’s no sexual tension (conflict) to play with anymore either.

But fear not. The writers seem to understand that if they don’t add SOMETHING to the scene, there won’t be any point to it. So they eventually DO introduce a “want.” Emily wants to go home. Kumail resists, wanting her to stay. We finally have our conflict, even if it’s conflict-light. And you’ll notice that the scene rises up a notch once Emily wants to leave. Now you have an action (her leaving) that can be played with.

The lesson here is you don’t need to introduce the “want” right away. You can introduce it later in the scene to change things up.

Now let’s talk about the early part of the scene, and something that separated this romantic comedy from so many others: SPECIFICITY. You can add a level of realism to dialogue exchanges by adding specificity. Read the first four lines in this scene. “What are these scars?” “Oh, they’re a small pox vaccination.” “I thought only old people had those.” “Well I’m from Pakistan. We’re still fighting some battles you guys have already won.”

When was the last time you read anything where small pox was mentioned? In a romantic comedy no less. Why that’s so important is because in four lines, we’ve separated these characters from every other character we’ve seen. That’s specificity. You’re creating a world that’s specific to this experience and this experience only.

That continues throughout the scene. We learn this very specific detail about how Hugh Grant never smiles because it makes him look fat. We learn that Emily was voted “Most Noticeable.” Seems insignificant, right? Well, when you’ve read over 300 scripts where the only time a high school yearbook is mentioned is to place someone in the “Most Popular” category (aka, the most obvious category), you can appreciate the push to give us something different.

How do Kumail and Emily achieve this? Well, they kind of have a secret weapon. They’re writing about their own lives. So (most of) this conversation really happened. That’s a cheat code. Since we’re not always going to be able to write characters based on ourselves, we don’t have this advantage. But you can apply the same approach by inserting specific moments from your own life into your fictional characters’ dialogue where relevant.

Another thing to note is that the dialogue has a certain realism to it. It doesn’t feel overly affected. A big reason for this is that there’s a playfulness during the moments where you don’t typically play. I’ve read scenes like this where amateur writers will play it straight-forward. “You’re leaving already?” “Yeah.” “We’re not even going to…” “We just did.” “I know but… maybe we could do it again?” “I’m tired.” He looks at her, disappointed. “Yeah, okay.”

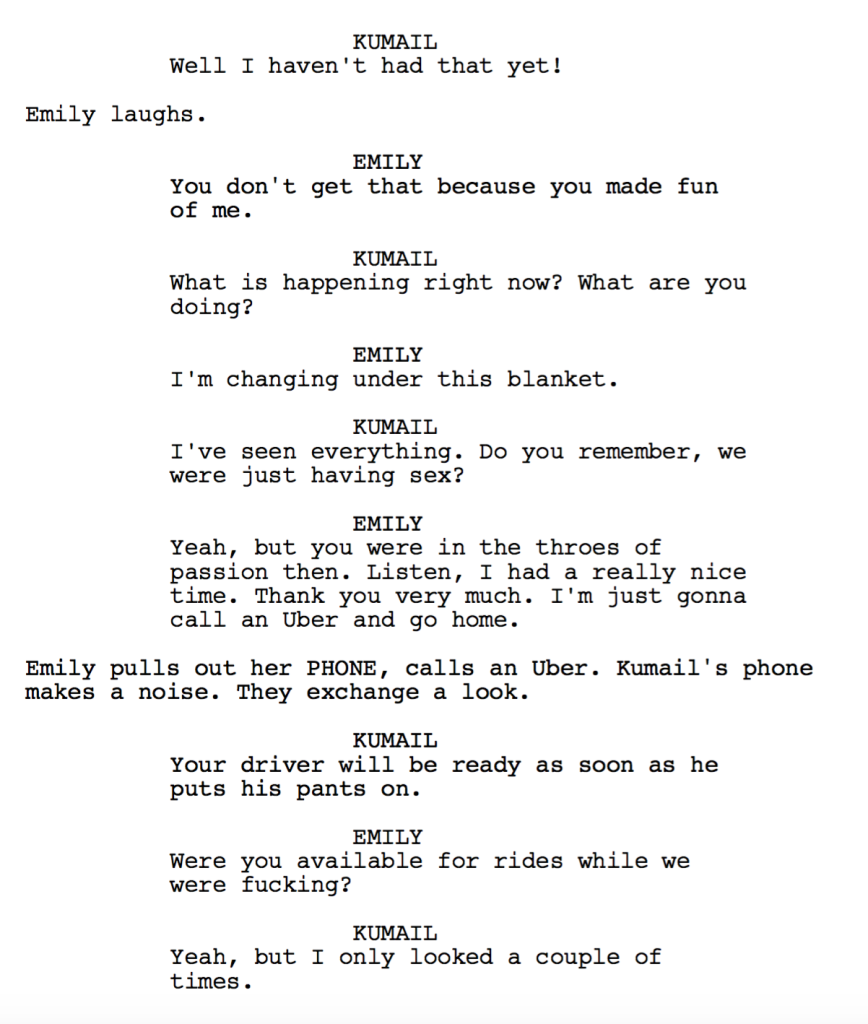

How much better is, “Wait we haven’t even had sex again yet.” What an awesome first line, right? He brings up something far from guaranteed as if it’s a given with every hookup. “No. No. I’m really not that kind of a girl. I only have sex once on a first date. Plus a hand job.” Another great line. The girl is NEVER supposed to admit to having sex on first dates. But Emily plays right along with Kumail. They then push the joke one step further. “Plus a hand job.” It’s great.

“Well I haven’t had that yet!” She laughs. “You don’t get that because you made fun of me.” “What is happening right now? What are you doing?” “I’m changing under this blanket.” “I’ve seen everything. Do you remember, we were just having sex.” I love this line. It’s something that so many people think but don’t say. We just had crazy wild sex yet you’re dressing in private? It makes zero sense. I call these “truth lines” and they almost always work. When you verbalize the TRUTH, you have hundreds of millions of people who will be able to relate to it. But if Kumail had turned away to be “respectful,” it would’ve read false. Especially with these characters.

The star of this scene, though, is the final joke. “Your driver will be ready as soon as he puts his pants on.” That’s the kind of stuff that’s hard to teach. Because not everyone is clever enough to come up with that joke. But I’ll say this. You can find these jokes if you put the effort in. The first step is not accepting an average joke. That means more trial and error. That means more time spent on the scene as opposed to moving on to the next one. That decision alone separates you from the pack. From there, it’s a matter of asking a lot of “What if” questions.

One way this joke could’ve been discovered is that they knew they wanted Kumail to drive Emily home, but how were they going to do that if Emily didn’t want to be driven home? Well… what if… when Emily called an Uber, Kumail ended up being the driver? It’s never as simple as that. But just by asking “What if?” you come across options other than the most obvious one, which would’ve been Kumail walking Emily to her Uber and saying goodbye.

To summarize, you probably want to avoid a scene like this. No big want. No huge resistance. Very little tension. Very little conflict. Characters sitting around with nothing to do but talk (they aren’t bowling, like yesterday’s characters). Without these tools, a scene becomes exclusively dependent on the writer’s ability to write good conversation.

The writers beat those odds by, first, adding specificity. But more importantly, they had fun with the scene. And you need to have fun in a scene if you’re not offering any dramatic value. Let your character go on for 7 lines on a Hugh Grant tangent. Let them bring up something as random as a small pox vaccination. These are the things that make conversation sound real in a “I’m a human so sometimes random shit comes out of my mouth” way.

What I learned: It’s not what you say. It’s how you say it. If you want to write great lines of dialogue, stop focusing on the WHAT and start focusing on the HOW. Early in the scene, Emily expresses confusion as to why a man living in the 21st century would have small pox scars. “Well I’m from Pakistan,” Kumail says. “We got the small pox vaccination late.” Okay, that’s not really what he says, is it? No. Because this is the WHAT version of the line. It’s straight forward info and therefore lands with a thud. Kumail and Emily the writers search for HOW to say this line so that it lands with more pop. “We’re still fighting some battles you guys have already won.” So much better right!? If a line isn’t popping, it may be a WHAT line. Make it a HOW!