This week has an interesting ring to it. I’ll be reviewing two scripts that deal with the same subject matter in very different ways, one with a well-known director attached and one that sold just last week. We also have a guest reviewer coming in to review Shane Carruth’s (Primer) long in-development project, Topiary, which I think is something like 200 pages long. I don’t know anything about it but you basically have to be a genius to write a 200 page script, or really bad at formatting, so we’ll see. Friday is still undecided but I’m sure I’ll find something to read. Right now, Roger reviews the recently sold, “Die In A Gunfight.”

Genre: Drama

Premise: A high society outlaw falls in love with the daughter of his father’s rival, endangering not only their reputations, but their lives.

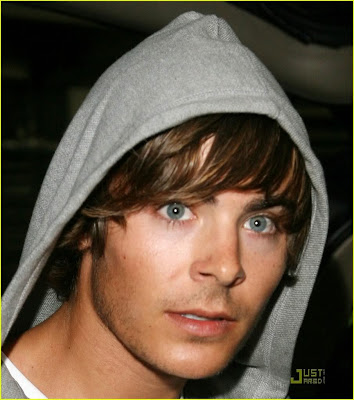

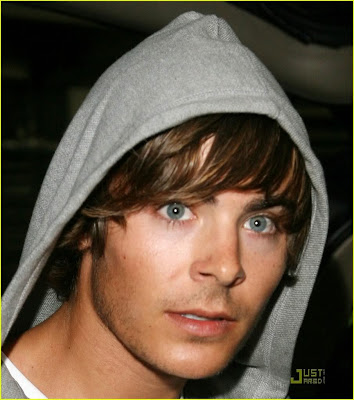

About: In one of those stories that’s sure to bring out the jealousy and set the bar very high for this writing team, Andrew Barrer and Gabriel Ferrari sold this script straight out of NYU. “Die in a Gunfight” is next in line for Zac Efron. A project with a risky role, this may be Efron’s meal ticket to cinematic coolness.

Writers: Andrew Barrer & Gabriel Ferrari

Details: June 2010 draft – 109 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Zac Efron seems to be smartly cultivating his dapper Disney star image while cautiously stepping outside his bubblegum box to show the rest of us that he’s more than just a debonair pretty face. Do I think it’s a stretch to compare him to Johnny Depp? I don’t know, but I present you with the John Waters connection: Depp eschewed expectation and chose Water’s Cry-Baby over all the other pap passed his way, perhaps paving the way for someone like Efron, who starred in a more mainstream friendly rendition of Water’s Hairspray. While Depp didn’t seem to care what people thought of him, Efron appears to be considering the ramifications of career suicide.

And, why wouldn’t he?

Which brings us to “Die in a Gunfight”, an idiosyncratic script that has all the clever transitions and style of a Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Wes Anderson mash-up, but sadly, lacks the substance of something like Amelie or Rushmore.

Mike Fleming over at Deadline Hollywood described this as a high octane action script. I guess that sounds good in a logline, but it’s not exactly accurate. Sure, it’s a tale bookended with violence, and the opening sequence definitely sets the tone for bloodshed, but this is not an action movie.

In fact, when it comes to genre, I’m not sure what it wants to be.

What’s it about, Rog?

We open with a Godard line, “All you need for a movie is a gun and a girl.” I think he says this with the expectation that we already understand character, story and plot. If not, then this script is an example that we should.

The first time we meet Ben Gibbons we see his feet. They’re scuffling. The camera pulls back and he’s scuffling with a bunch of guys who are beating the shit out of him. There’s a narrator. The narrator is also Ben, and he’s telling us that Ben has been in 723 brawls, about 38.05 per year, and he’s lost every single one. I’m not sure what .05 of a brawl is. Perhaps it’s a scowl.

Anyways, Ben is going to the latest charity event at the behest of his parents with his best friend and bodyguard, Mukul, an Apache Indian. Of course, when they show up at the event entitled, “An Evening with Sanje Padma (in support of the Good World Foundation)”, they are both stoned and Ben is wearing the facial bruises of his latest fistfight.

Yes, his parents are embarrassed, especially his father, Henry Gibbon, a lawyer whom is in the midst of the most important case of his career. There’s a confrontation with Henry’s courtroom nemesis, William Rathcart and his wife Beatrice. Although Henry is able to insult Rathcart verbally, the winning point goes to Rathcart when he turns his attention to Ben, shrewdly mocking the ambition of Henry’s progeny.

What does Ben want out of life?

Although he’s not sure, his grandfather has left him a trust fund, and he’s thinking about maybe running a video store. Mostly he likes to be a high society outlaw and anarchist, which we see when him and Mukul steal all the expensive fur coats from the courtroom while a portly Indian with a sitar tries to entertain the crowd with an interesting cover of “Freebird”. The socialites are used to rolling their eyes at Ben’s behavior, but this act catches the attention of a gal named Mary.

Who is Mary?

Mary is the daughter of William and Beatrice Rathcart. As a young girl, she was kicked out of every private school in Manhattan for “flabbergasting precociousness, unabashed coquettishness, pathological contrariness and preternatural indecency.”

Okay.

The Rathcarts resort to a private tutor, a shadowy character known in the script only as The Tutor, and when she’s of age, she goes to Paris, where she graduates from the Sorbonne. And what does this contrary Eloise want other than Ben? I’m not sure, although she dislikes her mother’s philosophy that she’s “only as good as people think you are.”

But, more importantly, she’s the daughter of the man that is defending a murderer named Phillip Lowman.

Who is Phillip Lowman?

No, you should be asking, Who is Terrence Uberahl?

Uberahl is the man Ben’s father is attempting to sue, the founder of Global Network, a company whose motto is, “Opening doors all over the world. The guy has supposedly invented a technology that makes transteleportation possible,

Lowman is suing Uberahl and Global Network because he says the tech literally destroyed his soul and caused him to murder a man. Apparently the tech disassembles a person at one location and makes a copy of them at another location. His argument is that when he was reassembled, the tech neglected to correctly assemble his soul.

The kicker is that if Ben’s dad wins the court case, he will have effectively proven the legal existence of the human soul.

Cool. So, what happens?

In one of the coats Ben stole, he finds a note with an address. Yes, the coat belonged to Mary, and the note is actually an invitation to a weird party that’s part rave and part Japanese tearoom.

The party is supposed to be a reunion for Mary with some classmates from the Sorbonne, Croatian twins named Snjezena and Svjetlana who like to dress up like geishas.

Mary arrives to fall in love with Ben when he gets into a brawl with a weird cokehead who is dressed like a Texas oil baron, and thus we begin a frustrating tale of star-crossed lovers that is destined to end in violence.

There’s a lot of talk about the human soul, a subplot involving The Tutor and Mary, and a showdown at a Halloween Gala with an oddly moving ending.

But…it doesn’t really work. Not for me, anyways.

Why doesn’t it work?

At one point I thought I was in store for something brilliant, something that chopped up the act structure and plot devices and beats of Romeo & Juliet and was streaming it through a filter of the French New Wave, Brett Easton Ellis and Kurt Vonnegut. But, like any script that does not utilize the tried and true pillars of successful storytelling, i.e. well-defined characters with goals and flaws, it collapses upon itself in the second act.

While an ambitious style (backed up by a stellar command of language) may keep me distracted for about thirty pages, the game will be up once I discover that there’s not a compelling story underneath all the cool transitions, flashbacks, narration, slow-motion and freeze-frames. If I get bored by redundant Godard-inspired dialogue passages where I’m supposed to be excited by a supposedly heavy subtext that isn’t propped up by the story at hand, then I know I’m reading something by a highly talented amateur that hasn’t nailed down his or her craft yet.

“True Romance” this ain’t.

It’s more Godard than Elmore Leonard, more inscrutable tone poem than clever plot framing a satisfying story of forbidden love. In a way, it reminds me of Richard Kelly, another filmmaker who has a great talent for tone but tells stories crippled by ambition and incomprehension. “Die in a Gunfight” lies somewhere in the story phantom zone of “Southland Tales” and “Donnie Darko”.

Sometimes we understand the characters. They don’t find identity, acceptance or satisfaction in the worlds their parents live in, and thus they rebel. We can understand what they want, which is a different way of life without the burden of how their parents expect them to act. But why can’t they just leave? Hell, Ben was left a shit-ton of money by his grandfather. He flees college at one point to go on an adventure in the West. He doesn’t seem to have to meet any conditions to have access to this trust fund, either.

And, sometimes, we don’t understand the characters. Ben’s flaw is that he has a death wish. Okay. I guess it doesn’t matter why (or does it?). Sure, we see him getting into brawls, which serve to tell us about his flaw, but it doesn’t seem like he really has a death wish. He never tries to commit suicide. Doesn’t even Juno try to do that with licorice rope when she’s looking for a way out of her predicament? In Luc Besson’s “Angel A”, Andre attempts suicide only to be distracted by a mysterious woman. This is not a real flaw. Perhaps Ben’s real flaw is his constant cry for attention.

The key here is to find the story underneath all the gimmickry and define it. If this is a story about two disaffected youth trying to escape their parent’s socialite world, it needs to feel realistic, urgent and high-stakes. They need to feel truly trapped. Their goals should be defined into plans to run away together, and there should be forces at work trying to keep them from each other and their plans. What the characters want and what they will do to get what they want feels like a side-note tacked onto the whiplash transitions that attempt to provide us with back-story and character but feel more like inconsequential tangents.

You know, Baz Luhrmann already stylistically retold Romeo and Juliet, and resetting a tale of forbidden romance in the world of Manhattan socialites doesn’t strike me as appealing as Luhrmann’s violent Verona Beach, but that doesn’t mean it can’t work.

But first, it has to make sense.

What exists on the page may make sense in the writer’s heads, but it doesn’t make sense to us.

Not yet.

But when it does, I don’t see why this couldn’t be Zac Efron’s breakthrough role into arthouse coolness. If not, maybe he could just star in the new John Waters movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Stories can be either be about characters, or they can be about ideas. Now, novels and short fiction, especially within the genre of science fiction, have more leeway to be purely about ideas. But with screenplays, especially spec screenplays, you’re taking a huge risk if you want your ideas to do the heavy-lifting for your characters. There were some Charlie Kaufman-like flirtations with brilliance in this script. Ideas and scenes that made me wish this script worked as a whole for me. A high-profile court case about transteleportation and murder that is essentially about proving the existence of the human soul? I think that’s pretty fucking sweet. There was a one-two punch concerning an Animal Planet program about dominance and family dynamics with gibbon monkeys that paid-off in a fantasy sequence when Ben Gibbons imagines himself challenging his father, Henry Gibbons, by throwing plates and swinging off chandeliers. That was cool. These are scenes and ideas that may work by themselves within the framework of the larger story. But, for me, the whole has to be greater than the sum of its parts. The main story being told has to work, otherwise the cool ideas just feel like window dressing.