Genre: Horror

Premise: After her plane crashes on a remote island, a young biologist fights for survival against a rapidly zombifying army of dead passengers.

About: Exposition Time. Last year, for one of my monthly Showdowns, I had a First Page Showdown. Contestants entered their first page. No information whatsoever about title, genre, or logline. Just the first page. The readers on the site then voted for the best one. This is the page that won. However, Mikael Grahn played a trick on us. He hadn’t actually written the script. Well, the script has now been written so I thought I would review it today!

Writer: Mikael Grahn

Details: 107 pages

With all this talk about the upcoming First Line Contest, I remembered that I never reviewed the FIRST PAGE SHOWDOWN contest winner. Of course, there were extenuating circumstances. But since I finally have the script, I figure we should review it. Yeah?

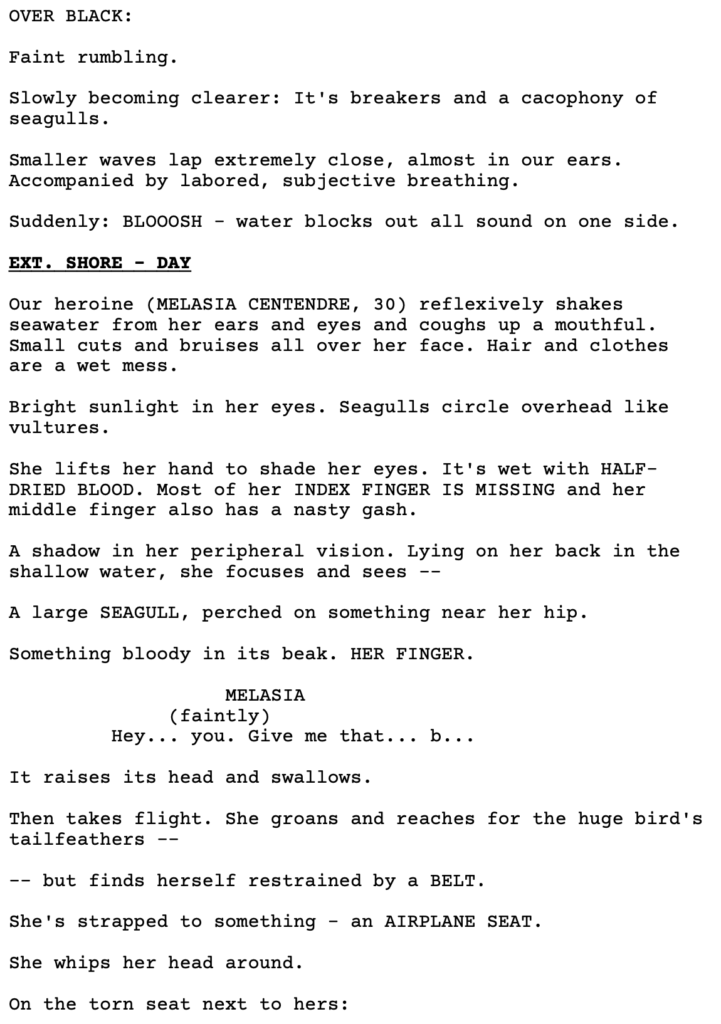

Before we do that. I want everyone to see the winning first page. This is the page that appeared on the site and won the contest.

Now, it’s time to see if the other 106 pages are as good.

Melanie Cardot wakes up in the ocean on a plane seat with dead people all around her. One of those dead people was her husband, who was in the seat next to her. Now he’s just a skull fragment and some hair.

Melanie crawls onto the beach and quickly saves a ferret from the plane who becomes her little pal. She’s going to need friends because moments later, one of the dead passengers in the ocean begins to crawl forward. Which shouldn’t be happening considering his skull is gone.

The good news is, it doesn’t seem to want to kill her. Yet. But her fortune dissipates quickly when she sees another headless man walking on the beach. This one in an orange jumpsuit. After getting the heck away from those guys, she finds a rescue helicopter where it appears the man in the orange jump suit came from. But where are the other rescuers?

Soon, more of the dead plane passengers are waking up. Melanie, who’s a biologist, starts to formulate a theory. Something is placing eggs in these bodies and these eggs birth some sort of insect that then takes control of the bodies’ nervous system, basically turning those bodies into vehicles.

Melanie heads up a nearby cliff where she runs into another survivor, an overly nice incel named Rudiger. The two, almost immediately, have to fend off some insect-zombie-dudes with whatever weapons they can find. For Melanie, it’s a jaws-of-life tool from the rescue helicopter. Now that they know what they’re up against, they have to find a way off this island. But how they’re going to do that is anyone’s guess. Cause they’re in the middle of nowhere.

Okay, so, it’s time to get real.

You ready to get real with me?

I read scripts like this alllllll the time. Scripts where people are in some contained location and zombies and/or monsters come after them. Just to give you an idea of how often I read them, I happened to read one JUST YESTERDAY for a script consultation. And I read one last week!

What I’ve learned by reading this particular setup over and over again is that there are two ways to make it work. One is if you give us a scenario or execution we’ve never seen before. Every aspect of the story feels fresh. Now that’s really hard to do because you’re competing against a hundred years of movies. But it can be done if you come up with a really original idea.

The far easier way to make these work, though, is through the characters. If you can create a character we love who is trying to overcome something inside of them and/or a small group of characters who have some unresolved conflict between them and you can explore it and resolve it in an emotionally compelling way, we’ll like your script.

I’m going to grade Niobiota on that scale.

Is this something we’ve never seen before? For the first half of the script, I’ve seen this setup a billion times. These are the same monsters you see in every first person shooter video game. However, later in the script, when they turn into full-on insects, they became more original. The problem was, by that point, the die was cast. We were already bored by the ‘been there done that’ monsters.

Grade: 6 out of 10

What about the character element? We have a dead husband, who was on the plane, so there’s a teensy bit of an emotional tug there. Melanie herself is a biologist, which, while not exactly common in these movies, isn’t that original either. Rudiger has the incel thing going, which was sort of different. But I never connected with anyone emotionally.

Grade: 5 out of 10

So if neither of those two things is near an 8 out of 10, it’s going to be real hard to keep a reader’s interest.

Which is why I say: GET THE HUMAN/PERSONAL/EMOTIONAL component right. Spend more time on that than all the bells and whistles of your concept. Because it’s the easier one to pull off. Why did The Last of Us video game become such a big hit? Because, up until then, zombie games were mindless shooters. The Last of Us developers put a premium on making you fall in love with the characters, connecting with them, giving them internal conflicts and flaws and backstories, and now you actually care what happens even if you go a long time without having to kill any zombies.

Getting back to the plot of today’s script, there were things that I didn’t quite understand. There’s a recurring theme about them disturbing this island. This island wasn’t meant for them. They’re “invaders.” Which is why they can’t be here.

For that reason, I thought these insects that laid the eggs were part of the island. I thought that was the physical manifestation of the theme we were exploring. This is why you can’t come to our island. Because we will infect you and destroy you.

But the insect egg thing didn’t originate on the island. It originated on the plane. So what does “we’re not supposed to be here” mean? Being on this island has nothing to do with anything that’s happened to them. Some crazy insect-infested dude on your plane is the problem.

I don’t know. Maybe I missed the point. But that’s the thing writers have to realize. If we’re not invested in your story, we don’t care enough to figure out the nuances of it. If it’s confusing, we won’t back up and try to figure it out. We’re not engaged enough to care.

This happened recently with Ari Aster and Beau is Afraid. In an interview he agitatedly complained that there were things in Beau is Afraid that people still weren’t talking about online. And it’s like, “Well yeah. Cause we couldn’t connect with your story.” If we don’t love the story, we’re not going to look deeper.

I do think that some of the aspects of Neobiota could be improved through subsequent drafts. I mean, the third act is a disaster and shows how quickly the script was written (It’s an entirely different story that has nothing to do with the island). The question is, is it worth it to perfect this script?

I’ll say this. There may be something here with these insects that control human and animal bodies. If they could emerge by the end of the first act so that you’ve established the uniqueness of your concept early? There could be a path to a fun movie there. But you need to dig way deeper with Melanie. She needs to be more likable and a more complex character and have a more interesting path. You’d need to replace Rudinger. He’s not working. And you’d need to rethink your third act. You can’t just start your movie over.

If you did that… I don’t know. You may have a movie. What do you guys think?

You can download the script here: Neobiota

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It was hard for me to look at this without thinking about how Mikael was rushed writing it. And while the majority of you will never be in the exact same scenario Mikael was in, you will be in scenarios where your time writing the script will come up in conversation. In those scenarios, always be vague. Never say you worked three years on a script. Never say you worked one month on a script. Those details WILL work their way into a reader’s head when they’re reading.

If they were told that the writer wrote the script in a month, the second a cliched creative choice pops up, they’ll think, “This is what happens when you write a script too fast.” Or if a script is really dense and heavily described, they’ll think, “This is what happens when you spend too long on a script. You overwrite it.” Just don’t ever mention that stuff if you don’t have to.