Submissions for the Logline Showdown need to be turned in tonight, Thursday, February 16th, by 10pm Pacific Time!

FINAL REMINDER that we’ve got the year’s SECOND Logline Showdown coming up this Friday. For those who don’t know what the Logline Showdown is, anyone can send me a logline at carsonreeves3@gmail.com. It must be a logline for a completed script.

I choose the 5 best submissions and place them up here, on the site, for you to vote on, over the weekend. Whichever logline gets the most votes, I review that script the following Friday.

If you want to enter, which is 100% free, here are the instructions:

Send me your title, genre, and logline. Nothing more.

Send it to this e-mail: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Send it by 10pm Pacific Time, Thursday, February 16th.

Now, on to today’s article!

Tuesday, after writing my review for Male Pattern Baldness, I noticed that something I wrote at the beginning of the review was a criticism I’d been writing a lot lately, in both scripts I reviewed and scripts I’d given notes on.

The observation was: This script started off strong then lost steam.

I’ve been writing that SO MUCH lately so I wanted to write an article exploring why this happens and what you can do to prevent it.

Let’s start with the why. Why does this happen? There are several reasons. But most of it comes down to jumping into a script before you’re ready. We’re all guilty of doing this. We get an idea on Thursday. We get really excited about it over the next 24 hours. Then as soon as work ends on Friday, we start writing like a maniac and bang out as many pages as we can over the weekend.

Those pages, while sloppy, *do* have a lot of energy in them – especially the first few scenes. But then once the high wears off, so does the energy. Each subsequent scene feels like a chore. Which can be demoralizing if you’re only on Scene 14 and, therefore, still have 36 scenes to go.

How do we prevent this from happening? The problem can be broken down into two scenarios.

Scenario 1 is ignorance. A writer doesn’t yet understand how to keep a story interesting from page 1 to page 110. They need to keep learning how to write a screenplay and how to tell a story (two different skills, by the way) in order to fix this issue.

Scenario 2 is laziness. The writer knows how to keep the reader invested. But he also knows that, to do so, it takes a lot of work. It’s hard to come up with a fresh captivating plot that keeps the reader on his toes. And they don’t want to do that work.

This is why you see professional writers write the occasional bad script. They start thinking everything they write is gold because why wouldn’t it be? They’re getting paid a lot of money for their words. So they just don’t do the hard work required to keep the reader captivated.

Most of the people on this site fall into the first category. They don’t yet know how to make their script captivating past that first act. If you’re part of the second category, all I have to say is shame on you. Cause if you know how to do it and you’re not putting in the work to do so? That’s screenwriting malpractice. Get your hands dirty, get in there, and do the necessary planning and rewrites that are going to result in a great read.

All right, now that we’ve brow-beaten the second category, let’s help everyone in the first category. How do you start off with a head of steam and never slow down?

Funny enough, that’s the first tip. You have to embrace the philosophy of grabbing the reader right away and never letting them go. This might sound like obvious advice. But every single day I read a script that doesn’t abide by it. The philosophy I more commonly encounter is, “Grab the reader right away, now I’ve earned the right to slow down, I’ll start making things fun again later.”

You really don’t have the luxury to take this approach in the spec script market. You have to make things move in every single scene. So if you simply embrace that philosophy of grabbing the reader and never letting them go, you’ll be ahead of 90% of your competition.

The next thing you need to get right is generating a concept that actually warrants a full 110 page story. The old industry saying is: “A concept that has legs.” A lot of concepts don’t have legs. And the frustrating thing about these scripts is that you’re trying to make a plane fly that doesn’t have wings.

Now, most writers don’t figure out their script lacks legs until three months into writing it. A question that can help you identify leggy concepts is: are you going to have trouble cutting your script down to 110 pages or are you going to have trouble coming up with enough story to get to 110 pages?

If your situation is the former, your concept has legs. If your situation is the latter, it probably doesn’t.

To give you more specific examples, a movie like “Fall,” which follows two girls who climb to the top of a radio tower and get stuck – that concept was doomed cause it clearly didn’t have legs. “The Whale” is another film that people have complained about for not having legs (literally, since the main character can’t stand up), which is why it’s not getting the acclaim everyone thought it would get.

Even though I didn’t love, “Nope,” that script, with its dying movie-horse ranch business, the family issues between brother and sister, the rival Old West theme park and the flying alien predator, gave Peele plenty of story to work with.

Just to be clear, I’m not saying simple ideas can’t have legs. If you include a robust main plot, plenty of characters, and a fully fleshed out world, you should be okay. But any story that has that juicy fun setup (like Fall) yet you can’t think up more than 5 scenes off the top of your head? Those are the concepts you probably want to avoid.

Next up, you need either a really compelling main character or a really compelling supporting character. The reason you need this is because it doesn’t matter how good you are at plotting or fleshing out your story if your characters are boring. You could be a master plotter and the reader is still bored because you haven’t given us someone we like to watch.

To create this character, you want to start out by either making them likable (Thor) or interesting (Arthur Fleck in Joker). The less likable your hero is, the more interesting they need to be. Cause if they’re not likable and only kind of interesting, we’re not going to root for them.

Then, you want to create a hole in the character’s life – a blind spot, if you will – that needs to be filled in order for them to become happy and whole. A recent example would be Evelyn from Everything Everywhere All at Once. She had given up on her family, convinced that she screwed up by marrying a weak husband and subsequently having a weak daughter.

She needed to fill that hole with love. We stuck around to see if she was going to do that (love her family again). If you do this right, you create the opposite effect of what I just outlined. Which is that, even if you’re not a good storyteller, we will want to keep watching to see if our hero fills their hole and becomes happy again.

You might wonder how character stuff “keeps the story moving.” That’s part of the magic of storytelling. A compelling character shortens time. We can’t get enough of them. So even if the story itself isn’t great, we’re lost in this character’s existence. And when that happens, time moves differently in our heads. We feel like the story is traversing through time faster.

Moving to the more technical side of things, you must know how to keep an engine underneath your story at all times, specifically throughout the second act, which is where most engines run out of gas, and the reader either doesn’t fill them up again or doesn’t introduce a new engine.

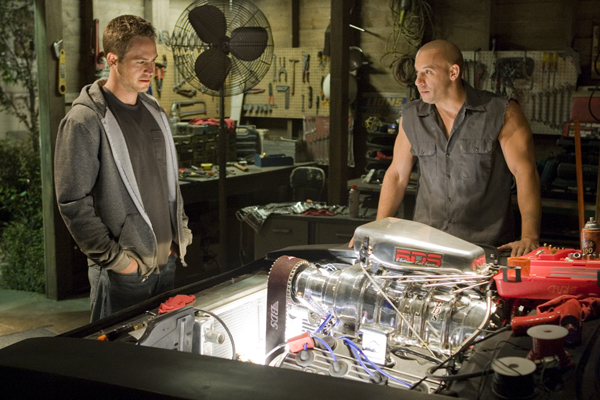

“I just don’t know if this is a big enough engine for our story, Turreto.”

“I just don’t know if this is a big enough engine for our story, Turreto.”

An engine is just goal + stakes. It’s a goal your heroes (or in some cases, the villain) need to achieve and it needs to be very important. In Avengers Infinity War, the goal is in Thanos’s hands. He wants the infinity crystals so he can snap half of the universe out of existence.

But that goal is achieved by the end of the movie. So, going into Avengers Endgame, you need a new engine. The engine switches over to the good guys, who decide to go back in time to get the crystals to reverse Thanos snapping half of the universe out of existence.

The thing to remember is that there always needs to be an engine underneath the story. If there isn’t, or if the engine has low stakes, that’s when your script starts to feel like it’s running out of steam.

If we use Tuesday’s script, Male Pattern Baldness, as an example, we can see just how the absence of a couple of these principles resulted in it losing steam. First, the main character wasn’t really that likable and wasn’t really that interesting. So pretty much before the story gets started, it’s screwed. But let’s be generous and say that maybe some readers related to the hero’s anger and, therefore, rooted for him.

While you do have a goal – he’s trying to get his wife back – I’m not sure the stakes are high enough. Do we really feel like, if he got her back, that he would be happy and everything would be good again? I didn’t. So the stakes weren’t high enough. We have to believe that the character’s goal is EXTREMELY important if we’re going to stay emotionally invested in the story.

All right, let’s summarize here. To make sure you don’t start strong then peter out, first embrace the writing philosophy of: grab them and never let them go. Next, make sure you have a concept that has legs. Next, give us a character we either like or find highly interesting. Give them a hole that they need to fill in order to become happy. Finally, make sure there is always an engine running underneath your story. If an engine completes its mission, introduce a new one.

And finally, understand that the way to make the rest of your script as good as the first few scenes, is through rewrites. You keep rewriting every scene until it’s just as energetic or dramatic or suspenseful or captivating or shocking as the first few scenes. If you take even one scene off, I promise you the reader will notice it. So do that extra work until all of your scenes are so good, the reader has no choice but to keep reading.

That way, I won’t have to write this annoying phrase – “I love how the script started but it ultimately ran out of steam.” – ever again. :)