So I’m sitting down last night and this question keeps circulating through my head. How does a writer like the writer of Resurrection do it? Why is his treatment of this idea so much better than everybody else’s treatment of it?

Cause I’ve read tons of scripts about men threatening women. I would venture to say over 500. What is it that this writer brought to the table that made this script so much better than the others?

Because I want to be a better writer. I want to learn from what Andrew Semans is doing. Even if you didn’t like Resurrection, you have to admit that the writing was a thousand times better than similarly themed Black List scripts like An Aftermath and The Tip.

Whereas Resurrection feels like it’s been written by someone with complete control of his craft, those scripts felt like they were written by 9th graders.

I mean, literally, it feels like they could’ve been written by a freshman in high school. That’s how simplistic the choices were, how basic the writing was. What is it that Andrew Semans is doing that these other writers are not?

The answer is on page 3. That’s the page in the script where I knew this was going to be good. I had a sense after reading this page that this writer was a cut above. So let’s take a closer look at the page and see what we can learn.

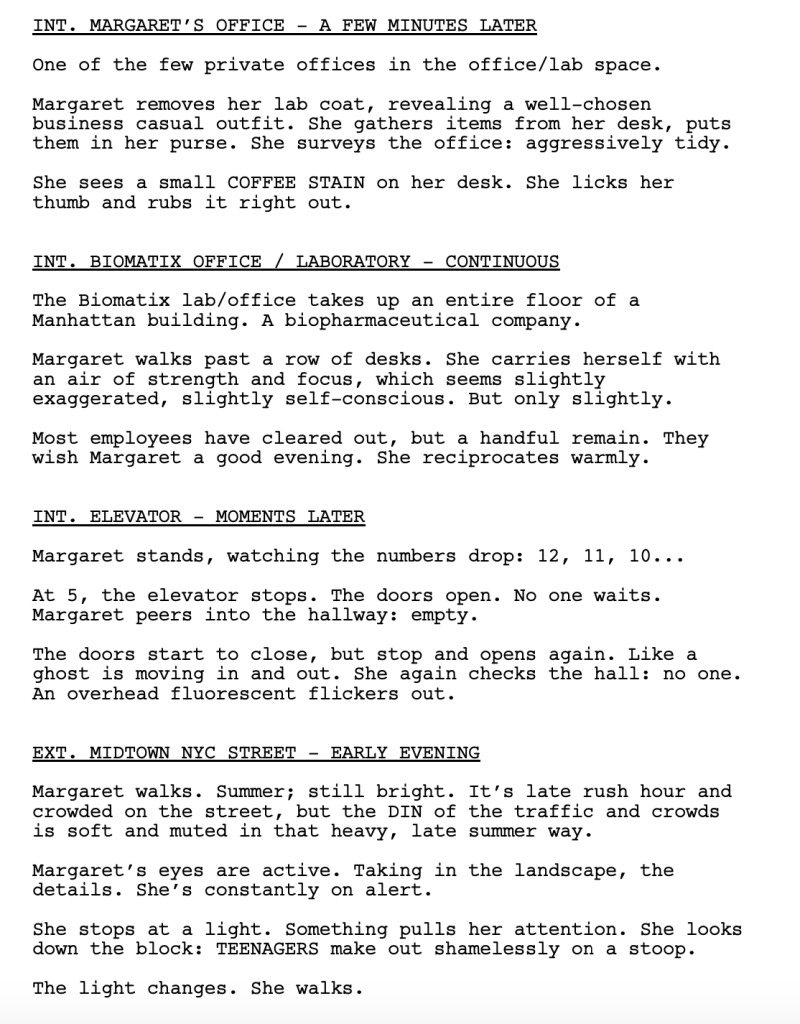

Let’s start with this line: “Margaret removes her lab coat, revealing a well-chosen business casual outfit.”

One of the ways I determine good writing is by contrasting what’s written with what could’ve been written. In this case, we’d usually see the line, “Margaret removes her lab coat.” The average writer would not have said anything beyond that. And that’s okay. You don’t have to tell us what the character is wearing under their lab coat. But it’s an opportunity to give us more information about the character. And since it’s early, it’s a good idea to do this.

So we’re told that Margaret is wearing a business casual outfit. On its own, nothing to note. But Semans adds a qualifying detail, that it’s “well-chosen.” Now THIS tells us something about the character. It conveys that she cares about what she wears. A small detail, yes. But already I know more about this character than I do most characters 50 pages into a script.

“She gathers items from her desk, puts them in her purse. She surveys the office: aggressively tidy.”

It’s another small thing. But the office isn’t just “tidy.” It’s “aggressively tidy.” This conveys a certain level of obsessiveness. It is painting a character before our eyes.

“She sees a small COFFEE STAIN on her desk. She licks her thumb and rubs it right out.”

A couple of things to note here. One of the best ways to tell us who a person is is through what they WEAR and what they DO. Semans has told us about the character through what she’s chosen to wear. And here Margaret does something – a small obsessive action – that further gives us insight into what kind of person she is.

“Margaret walks past a row of desks. She carries herself with an air of strength and focus, which seems slightly exaggerated, slightly self-conscious. But only slightly.”

Again, we’re taking a very simple action – walking – that most writers take for granted. To the average writer, walking is walking. To the experienced writer, walking can tell us a whole lot about a person. So I thought it was cool that Semans broke down Margaret’s walk into such specific detail. Even going so far as to point out that the slightly exaggerated self-conscious strength in her walk was only barely perceptible.

Semans is leaving nothing to chance here. He’s channeling as much specificity as the screenwriting medium will allow him. The more specific you can get about what we’re seeing, the more you’re going to channel your voice as a writer.

“They wish Margaret a good evening. She reciprocates warmly.”

Even this line, which seems like a throwaway, gives us some insight into Margaret’s character. A writer could’ve easily stopped at “They wish Margaret a good evening.” Hell, some writers may not have even chosen to tell us that. But that follow-up sentence, again, gives us a little more of a look into her head. The fact that she’s reciprocating warmly says she cares about this job and the people she works with.

“Margaret stands, watching the numbers drop: 12, 11, 10…

At 5, the elevator stops. The doors open. No one waits. Margaret peers into the hallway: empty.

The doors start to close, but stop and open again. Like a ghost is moving in and out. She again checks the hall: no one. An overhead fluorescent flickers out.”

This was a key moment in the script for me. If you think of a script as a cowboy with a lasso, this was the moment the lasso slid around me and tightened. There’s no reason that this moment needs to be in the script. It doesn’t play into the plot at all.

But what it does is it sets an atmospheric tone for the script. That this is going to be something where you don’t feel safe. Where you think you someone might be coming towards you but it’s only your imagination. This is where a writer’s voice can really come out. When they choose to include moments that don’t technically need to be in the script, but they put them in anyway for whatever reason. I can only guess what Semans was thinking here but I believe he wanted to set the tone of feeling vulnerable.

And he does it in such a visual way. It’s hard not to feel like you’re there on the elevator with Margaret with these visuals he keys in on (“peers into the hallway: empty” “The doors start to close, but stop and open again.” “An overhead florescent flickers out.”).

“It’s late rush hour and crowded on the street, but the DIN of the traffic and crowds is soft and muted in that heavy, late summer way.”

This is where Semans really separates himself from other writers in my opinion. He takes a common visual – late rush hour in the city, and paints it in a way that differentiates it from every other rush hour scene we know. He uses contrast to point out that the traffic and crowds are “soft and muted,” and he continues on to clarify that feeling – “in that heavy late summer way.” I don’t know about you. But I don’t know many people who would describe rush hour this way. It takes an acutely aware writer to key in on the subtleties of common practices to write a line like that.

“Margaret’s eyes are active. Taking in the landscape, the details. She’s constantly on alert.”

Again, look at how much Semans is telling us about Margaret in this page. The fact that she’s “constantly on alert” is a huge window into her persona.

“She stops at a light. Something pulls her attention. She looks down the block: TEENAGERS make out shamelessly on a stoop.

The light changes. She walks.”

A lot of writers have gotten lost in this screenwriting rule that you should only write what’s necessary and nothing else. And to an extent, I endorse that rule. But as you can see here, you can use mundane moments to not only tell us about your characters but set an atmospheric tone to the movie. As long as you’re exploring these moments with purpose – in this case to both tell us about our hero and set a tone for the movie – it’s fine to work with these “unimportant” moments.

That’s a big reason why Semans voice stood out from everyone else. Everybody else is following the rules so closely that they all sound exactly like each other. You have to look for places in your writing where you can show off your voice more. Because if you follow every rule to the letter, you’re writing a technically perfect but artistically inert screenplay.

And yes, I realize that how you write will be determined by what you write. You wouldn’t write this way if you were writing an Avengers movie. But if you want to stand out – and standing out is one of best ways to get recognized as an amateur writer – you should take a look at what Semans does with Resurrection.

One of my biggest takeaways from this script is that it’s not what you do with the broad strokes. It’s what you do with the details. It’s what you do in the cracks that separates you from everyone else.