A little while back, I was reading a murder-mystery consultation script. The opening scene covered the murder our detectives would spend the next 100 pages trying to solve.

Teaser scenes tell me a lot about a writer. Their construction is such that you can have a lot of fun with them, almost make them into a mini-movie. So if a writer can’t entertain me with their teaser, there’s a good chance they can’t entertain me for the next hour and a half.

Anyway, this murder scene takes place in a dorm room (I’m adjusting the actual details in order to keep the plot private). A stalker sneaks into the dormitory, makes his way up to his target’s room, and tricks her into opening the door. The rest of the scene takes place over one page and consists of the girl struggling a little bit but the killer easily subduing and, eventually, stabbing her to death.

The scene was extremely boring to read and I asked myself, “Why?” Technically, something exciting was happening. A girl was getting attacked. She was fighting for her life. And in the end, she sadly gets murdered. In what scenario is a murder “boring?”

The answer to this question is complicated but I’ll try and simplify it for you. In the real world, a murder is anything but boring. In a movie, however, people get murdered all the time. And because they’re fictional, the audience isn’t fazed by their death. So, in the context of storytelling, a murder can be just as boring as two characters talking at a diner.

But why was *this* scene so boring?

I had to keep reading the script before I noticed a pattern that ultimately identified the problem.

Anybody here a fan of Gwen Stefani’s old band, “No Doubt?”

That was the problem.

There was NO DOUBT within this opening murder scene that the murderer would succeed. There was never once where the girl got the upper hand. Or tried to talk the murderer out of it. The scene was a foregone conclusion. And foregone conclusions in the medium of storytelling are the equivalent of death. There is nothing that brings on boredom faster than a foregone conclusion.

I want you to imagine a see-saw. On one end of the see-saw is DOUBT. On the other end of the see-saw is CERTAINTY. Now I want you to imagine each one of your script’s 50 scenes as a person. Every time you write a scene where the outcome is certain, you are adding a person to the “Certainty” side of the see-saw. Before long, you’re going to have twenty people sitting on the Certainty side and, by sheer accident, one or two on the Doubt side.

How do you think a script like that reads? I’ll give you a hint because I read all these scripts. IT READS BORING.

Now it just so happens that I’ve been coming across a lot of suggestions to check out the old murder-mystery show, “Columbo.” I’d never seen Columbo before. Something about it put me off though I could never identify what. But I’m always willing to give something a shot.

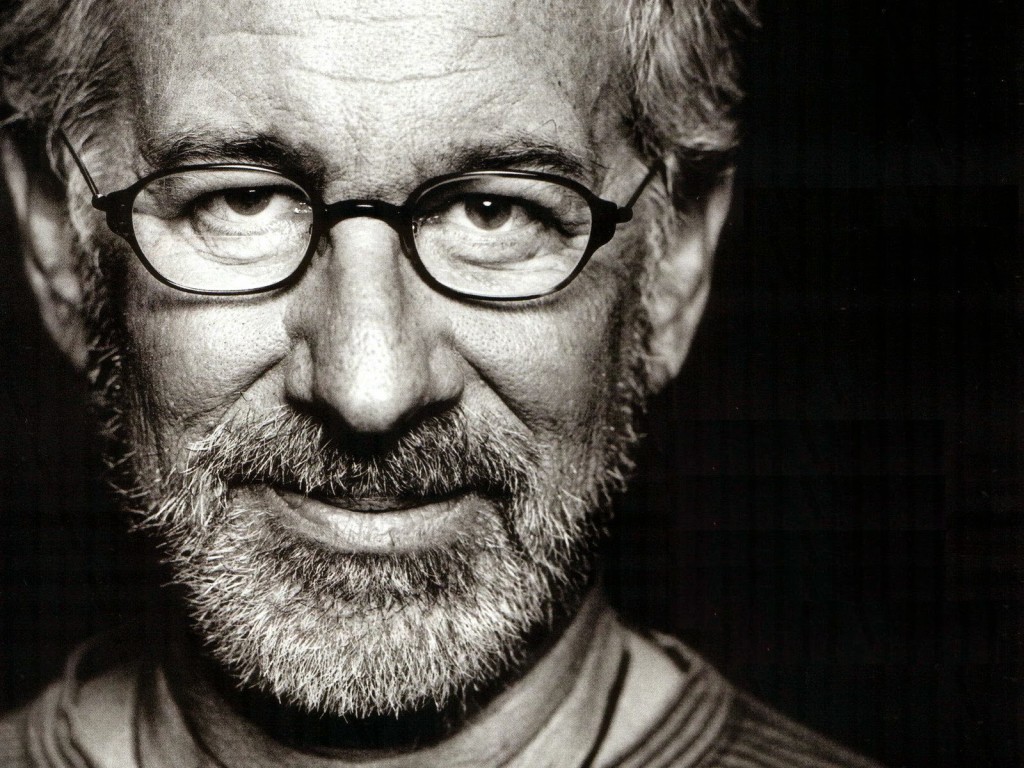

So I watched the second episode (due to some confusion, I thought it was the pilot). By the way, before I get to the analysis, I suggest all of you check it out. The story is about writers who live in Los Angeles so there’s plenty of familiar territory to appreciate. And it was directed by Steven Spielberg!

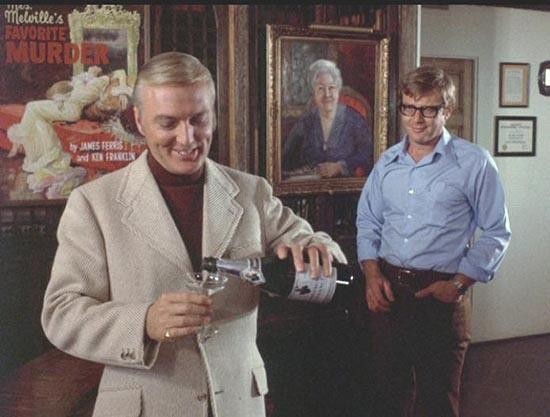

‘Murder by the Book’ introduces us to Jim Ferris, one half of a successful murder-mystery writing team. Jim is up on the 30th floor of his Century City office all alone for the weekend doing some writing. There’s a knock on the door.

He goes to open it and his co-writer, Ken Franklin, is standing there with a gun pointed at him. At this moment, we know what’s going to happen. These two are a writing team that are coming to an end. Ken wants all the money for himself so he’s going to kill his partner. It’s as certain as certain can get.

But then, oddly, Jim smiles. “Nice try,” he says. “What?” Ken replies. “You wouldn’t kill me with that gun. You’re not wearing gloves. Your fingerprints would be all over it. We’re murder-mystery writers. We know this stuff.” Ken smiles and lowers the gun. “You got me,” he says, and proceeds to walk past Jim into the office.

Notice what’s transpired. We were certain something was going to happen. Ken was going to kill Jim right there. But it turns out we were wrong. Ken was just playing around. The writer of this episode, Steven Bocho, had now injected some DOUBT into the scene.

Ken is still going to kill Jim though, right? We don’t have a procedural if there’s no murder. But even after Jim closes the door, Ken seems to relax. Is he going to kill him? (DOUBT). We learn a little more about the situation. The two are splitting up. Jim, it turns out, wants to move away from mystery writing and take on more serious subject matter.

Still, even though it seems like Ken is up to something, we’re not clear what his plan is. There are several moments he could kill Jim in the office yet he doesn’t (DOUBT). Ken eventually makes a pitch that they drive down to his house in San Diego and celebrate their big split with some champagne and good conversations. Reminisce about all the good times they had.

Jim is a little reluctant but eventually concedes. The two walk down to Ken’s car, which is all alone in the parking lot. But when they get inside, Ken “remembers” that he left his lighter up in the office. “I’ll be right back,” he says. I was absolutely certain that the second Ken was twenty steps clear of that car, it was going to blow up.

But it didn’t. Even more DOUBT.

At this point I was so curious how and where this murder was going to happen that I was hooked. I’d reached that point in a show or movie where you stop analyzing and start enjoying. And I can confirm to you that the primary reason for that was the level of doubt Bocho and Spielberg infused into the scene.

You see, most writers think of scenes as a sprint. Get from Point A to Point B as quick as possible. Good writers think of scenes AS A DANCE. And DOUBT is like a good set of dance shoes. It really allows you to get jiggy with a scene (or an entire narrative).

I was doubting how Ken was going to kill Jim ALL THE WAY UP TO, literally, the second the murder happened. That was how well-constructed the doubt was. And, by the way, this is from an episode of television 50 YEARS AGO. Think about that for a second. This writer was able to fool a viewer after 50+ years of similar content, much of which was inspired by this show.

That should tell you just how valuable the tool of DOUBT is in storytelling. It doesn’t matter how seasoned the viewer is. With some carefully placed moments of doubt, you can stay ahead of any viewer.

Some of you may say, “Well, sure, Carson. If I had 15 minutes to write an opening murder scene, I could create plenty of doubt too.” Which is a valid point. But you don’t need tons of time to create doubt. All you’re looking for is to make the viewer think the scene could go one of two ways. That doesn’t take much. It could take one moment that creates doubt.

Let’s go back to that opening consultation scene. What could we have done to create doubt? Well, the college girl is the potential victim here. So what you want to do is give us at least one moment where we think she’s going to escape. For example, the killer gets inside her room, corners her, and there’s a scuffle. It’s intense. She’s fighting hard. She somehow manages to stun him enough to get around him and run for the door.

Just as she grabs the doorknob, though, she’s dragged back. Even that moment – right up until she’s grabbed – is going to give the reader hope that she might get away. In other words, they’re doubting that the murderer will succeed. And if you really want to have fun, take the character as close to escape as you can before ripping it away.

For example, maybe she gets away A SECOND TIME and this time she DOES open the door. And she DOES run down the hallway. But it’s winter break. She’s the only one on the floor. So she’s screaming for help but nobody’s around. The killer is able to catch her again and murder her right there in the hallway.

How much more exciting is that scene than the killer easily walking through her door and easily killing her in her room? Way more entertaining right? That’s the power of DOUBT. Let it become a major part to your writing.