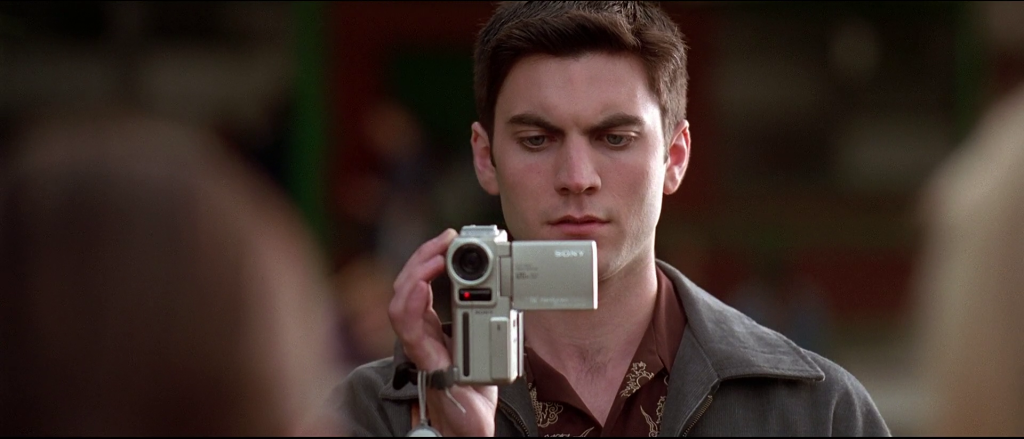

Do you have the next American Beauty?

Do you have the next American Beauty?

Tomorrow’s the official announcement for The Scriptshadow 250 Contest so I thought I’d talk a little about how to improve your chances in the competition. One of the differences with this contest as opposed to others is that I’m not trying to find a “contest-winning” script. I’m trying to find a MOVIE. That means a screenplay that can be turned into a film. That’s because unlike other contests that just give the winning writer money or pass his script to other people, the winning script here will be optioned by a producer with the ultimate intention of being turned into a film.

So what does that mean, exactly? Does that mean I’m only looking for the next Matrix? No, although I’d certainly be happy with the next Matrix. But if you’ve got the next American Beauty on your hard drive, I’m not going to be opposed to it. I think the idea here is to take a step back and try to objectively see your movie in today’s market. Does it look like a film that a studio would release? Or is it so obscure and so unique that it’d be lucky to land a one-week featured spot on Itunes? I would never close myself off to any script – especially because the smaller ones tend to be the most original. But know this. The more obscure and “indie” your concept is, the better the writing will have to be.

In addition to concept, I’ll be looking for character. In general, the more mainstream your idea is, the less you’ll have to worry about getting a movie star. So if you’re writing the next Kingsman, your lead doesn’t have to be some uber-complex mastery class in character development. But if you’re writing something smaller, a compelling unique character with depth is probably going to be your only shot at winning. That’s because the smaller films need name actors to get made. And name actors are only going to sign on to your script if you offer them a challenging role.

Ideally, you’ll look to create compelling characters no matter what you write, if not for the main role, then in a major supporting role. Take movies like Kingsman, Godzilla, or Pirates of the Caribbean. The lead characters were 20-somethings without much depth. But each script had a role (Colin Firth’s Harry Hart, Bryan Cranston’s Joe Brody, Johnny Depp’s Jack Sparrow) with more meat. And again, the smaller the movie you make, the more character exploration you’re going to have to do. I personally like movies with main characters who have relatable flaws and who change over the course of their journey. That’s why I love films like The Matrix and Good Will Hunting. Take a character on one end of the spectrum and bring him to the other end by the end of the film.

There are really two kinds of movies you can write – so let’s go over both of them. The first is the traditional straightforward “been done before” concept. This might be a thriller like The Equalizer, a comedy like Ride Along, or a sci-fi like The Maze Runner. If you’re writing this kind of film, you’re going to need to knock it out of the park, because people have already made these films a thousand times before. So your execution is going to have to be perfect. I’m not saying not to write these. Only that your writing will have to be perfect – since, as a concept, these scripts have all been done already.

The second kind of movie is when you take a traditional idea and find a fresh angle to it. We were just talking about this the other day with The New World. Jenji Kohan didn’t just write a pilot about people moving to the new world, which had been done before. She focused specifically on the female angle. You can do this with genre as well. Instead of writing the super straightforward rom-com The Wedding Planner, write 500 Days of Summer. Instead of writing a traditional sci-fi like The Maze Runner, write Edge of Tomorrow, which uses the Groundhog Day approach of rebooting every day. Instead of writing yet another stuck in the middle of a city with slow moving zombies everywhere zombie flick, turn it into a big action zombie film like World War Z.

Concept creation is what separates the women from the girls, the amateurs from the pros. Newer writers tend to give us the same old thing, whereas pro writers know that they have to bring something different to the table to get noticed. If everything I wrote above is confusing, then here’s a simplified version: Try to come up with something we haven’t seen before. If you can do that AND make it marketable (like The Hangover), then you have a huge leg up on the competition. And one more thing – test your concept on others before you write it if you can. You can save yourself a hell of a lot of time if five people tell you your concept is boring. You can move to the next one and give yourself a better shot, not just with my contest, but in general.

Here are some other thoughts. I’d strongly recommend you outline your script. I can tell 99% of the time when a writer hasn’t outlined because their script starts falling apart around the page 40 mark. You can tell they haven’t really thought of anything beyond the general concept and are therefore spending the back half of their script treading water until they can get to the climax. One of the key reasons to outline is to make sure your script stays exciting all the way through. So make that the goal as you’re planning your story. Make sure page 70 is just as exciting as the inciting incident on page 15.

Another easy toss-away for me are lazy scripts. Lazy scripts universally consist of writers who take scenes off. Here’s some life-changing advice for screenwriters: MAKE EVERY SCENE AS GOOD AS IT CAN POSSIBLY BE. That doesn’t mean each scene needs to be a showdown between your hero and villain. But even if a scene is mainly there for exposition, look for ways to still make it entertaining or compelling. The best writers NEVER TAKE SCENES OFF. They make sure every scene is the best they can make it. I know a script is done whenever I read two bad scenes in a row. And sadly, that usually happens within the first fifteen pages. Don’t be that writer!

One last thing. Dialogue should not be a venue for your characters to say exactly what’s on their minds or to state the obvious. In dramatic situations, people tend to hide their true motives and feelings and talk around issues. The best dialogue typically comes when at least one of the characters in the scene is keeping key information from the others. Characters will say what’s on their minds in confrontation scenes, but confrontation scenes tend to only happen a couple of times in a script (once around the middle, once near the end). “Flashy” dialogue (Juno, When Harry Met Sally, most comedies) is a different story. This is where clever fun dialogue is driving nearly every scene. This kind of dialogue is extremely talent-dependent so be honest with yourself that you’re that kind of writer before you commit an entire script to this style.

Truth be told, I’m just looking for something great. And if you’ve got that thing even though it goes against everything I just said, by all means, submit it. Rules are meant to be broken and rewritten, and the best scripts usually accomplish this on some level. But the above guide is based on reading thousands of scripts that have made the same mistakes over and over again. So, at the very least, keep it in the back of your mind.

Tomorrow, the competition begins. I can’t wait. Good luck!