Today’s article is dedicated to Steph, who’s been struggling to gain traction with her “two old ladies stuck on an island” screenplay.

As she’s said herself, something about the idea isn’t popping enough to get people interested. And so I asked the obvious question. Why? What is it about this idea that isn’t working?

To me, it comes down to a hook. There’s nothing in the idea that’s hooking me. But then I thought of some other movies that have been successful, movies that arguably didn’t have a hook either. Did Bridesmaids have a hook? The pitch for that movie is: “Bridesmaids being catty.” That’s not a hook. Yet it made a boatload of money and even got an Oscar nomination!

This necessitated today’s question. What is a hook? As well as a follow-up question. Does having one matter?

In looking back through recent hit movies over the years, and in examining the myriad of ways in which those ideas were appealing, I came to the conclusion that there wasn’t a one-size-fits-all definition for a hook. But I did find some patterns.

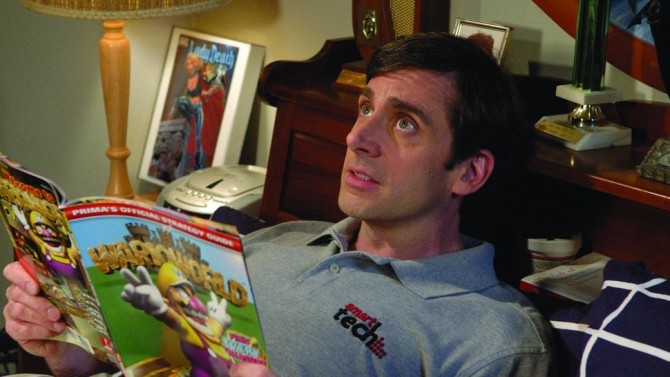

The biggest factor in determining a good hook is heavy contrast. Take The 40 Year Old Virgin, a movie with a hook so strong, you could sell it in the title. Let’s say that movie was renamed “The 17 Year Old Virgin.” Do you notice how quickly that idea went from “I’ve got to see that,” to “So what?”

That’s because there’s no contrast in the two elements. There are hundreds of millions of 17 year old virgins and therefore nothing unique about their situation. But when you’re 40 years old, you’re not supposed to be a virgin anymore. The contrast between those elements is heavy.

Since Steph’s idea follows a couple of older folks, let’s look at the number one movie on Itunes right now, which stars everybody’s favorite 80-something actor, Clint Eastwood. That film follows an old man who needs money and therefore agrees to be a drug mule. Drug-running is a young man’s game. There’s a high level of a contrast, then, in making our mule an 80 year old.

Let’s go back a bit further in time for our next concept, as it also shares some DNA with Steph’s idea. Lord of the Flies. A group of boys get stuck on an island and start warring against one another. To understand why this is a hook, all we need to do is substitute our kids for adults. “A group of men get stuck on an island and start warring against one another.” That setup is painfully obvious. The main elements, “men” and “war,” have been synonymous with one another since the dawn of time. By changing “men” to “boys,” you create a strong level of contrast. Innocent little kids aren’t supposed to war. Hence, you have your hook.

When looking at Steph’s idea, I’m struggling to find any contrast. I suggested to Steph that even if she changed one of the characters to a young man, the idea becomes more appealing because at least, then, you have contrast between the characters. But even then, there isn’t enough contrast to constitute a hook. That’s the trick with creating a hook. The contrast has to be overt enough to grab people’s attention.

But contrast isn’t the only way to create a hook. Where’s the contrast in Alien? Where’s the contrast in The Hangover? In these movies, a different kind of hook emerges. What is it?

With The Hangover, the hook is less about contrast and more about finding a unique way into a familiar scenario. We’d seen men going crazy at bachelor parties before. But we hadn’t seen a movie strictly about the day after, where the bachelors couldn’t remember anything yet must solve a mystery. With that said, there still needs to be an element of cleverness to the concept. If the pitch was, “A movie that focuses on a bachelor party before the bachelors go out for their big night on the town,” well, sure, that’s a unique way to explore the bachelor party setup, but there certainly isn’t anything clever about the idea, and hence it falls flat.

Any scenario that feels too familiar will fail to hook an audience. Ron Howard directed one of the blandest concepts I’ve ever come across. It was called “The Dilemma” and it was about a man who discovers his best friend’s wife is having an affair. The “dilemma” is whether he should tell his friend or not. Since there are hundreds of millions of instances in history where people cheat on their spouses, the idea was simply too familiar to be a hook.

Another common factor I see in a lot of good hooks is high stakes. The idea feels like it matters. In two of the concepts I’ve highlighted above, The Hangover and Lord of the Flies, the stakes are sky-high. In one, the wedding, as well as the groom’s life, are on the line. And in Flies, little kids’ lives are on the line. The stakes even feel high in The 40 Year old Virgin. If he doesn’t get laid with the help of these guys, he may die a virgin.

So what about Alien? Where’s the hook there?

This one had me miffed. There’s no contrast. The idea wasn’t exactly clever. What’s the hook? Then it hit me. In 1979, when that movie came out, it was a unique scenario. People stuck in a spaceship with a killer alien hunting them down. That’s one of the primary directives of a good idea – You want a combination location and threat that we haven’t seen together before.

Finally, you want an inherent sense of conflict in your idea. The more conflict within the idea, the harder it’s going to land. The Martian. A man who must live off a dead planet while he waits for a year to be rescued. The conflict between man and planet is extreme. It is a completely unforgiving place.

Which brings me back to Steph’s idea. There isn’t enough conflict to get me excited about the scenario. I suppose there are stakes in that they have to get off the island or they die? But I’m failing to see anything unique or exciting about what happens in the meantime.

Despite all of this, I still find that there’s a level of gray when it comes to hooks. What hooks one person doesn’t always hook the next person. I still don’t know what the hook to Bridesmaids is. Which tells me that a hook isn’t required to write a successful screenplay. But it does give you a huge advantage. There’s nothing quite like having an idea that speaks for itself, that you don’t have to convince people of. So I’d recommend everybody, especially unknown amateur screenwriters, write screenplays with strong hooks.

I’d also love to hear your thoughts on what you think makes a good hook. Maybe we can use Steph’s idea as a discussion point and, ultimately, help her find a hook for her movie.