If you asked 100 of Hollywood’s top producers, directors, actors, and writers, who the hottest screenwriter in the world was at the moment, the majority of them would say Phoebe Waller Bridge.

Bridge is killing it all areas of screenwriting but the thing she’s best known for is her dialogue. It’s been a long time since we’ve had a screenwriter whose dialogue was this celebrated, so I thought, why don’t we break some of her dialogue down?

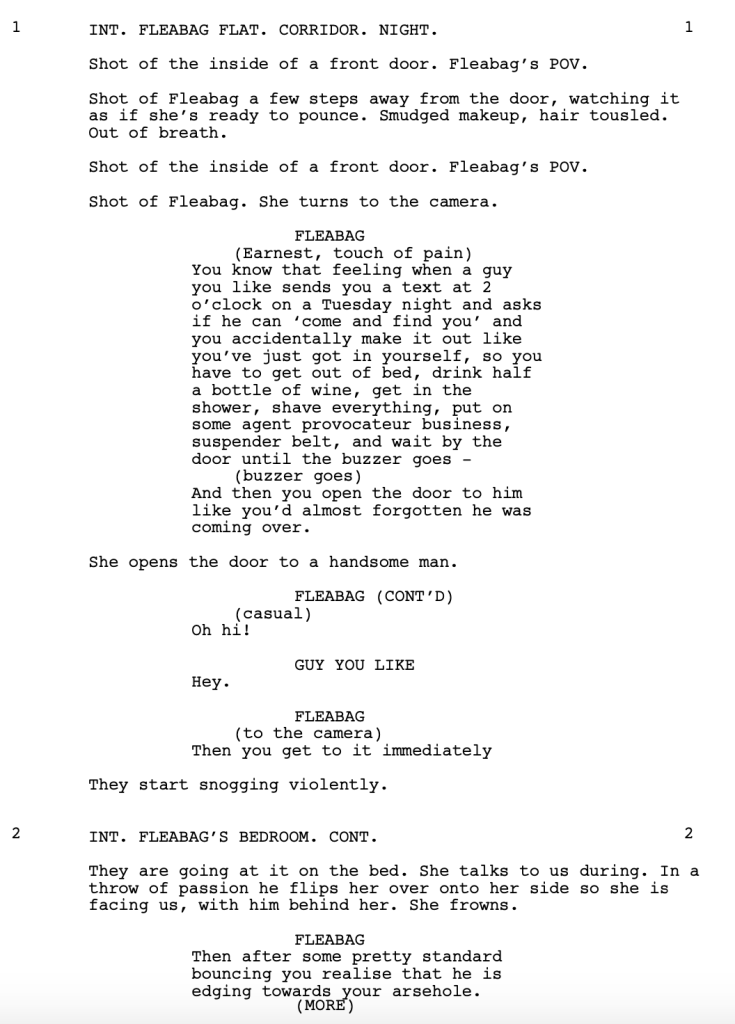

And what better scene to dissect than the opening scene of the Fleabag pilot. Do not worry if you’ve never seen the show. I’m going to include the pages here for you to read.

The first lesson for why this dialogue is so great is our most important one. Fleabag is a talker. She’s the definition of a dialogue-friendly character. One of the biggest mistakes writers make is they try and inject punchy dialogue onto characters who wouldn’t say those things. Imagine putting John Wick in this scene. He’s not going to give you anything close to what Fleabag is saying because John Wick operates with his gun, not his tongue.

So if you’re ever anxious about writing good dialogue in your script, the job starts long before you’ve written a word. You want to conceive of a primary character – it doesn’t have to be your hero but it does have to be a key charcter – who likes to talk or who says interesting things or who says controversial things or who’s clever or who’s funny or who’s weird or who talks first and thinks later. This decision will dictate 90% of the quality of your dialogue.

The next thing we’ve got going here is that Fleabag talks directly to the viewer. Now some people hate characters who do this. I get it. My feeling has always been, if you’re going to do something that ballsy, you better have the skills to back it up. There’s nothing worse than a “clever” character talking to the camera who’s a big fat ball of lame.

But assuming you’re good at breaking the 4th wall, doing so achieves a unique effect. It both breaks the monotony and it breaks up the predictability of the conversational flow. You’re no longer dependent on His Turn to Talk, Her Turn to Talk, His Turn to Talk, Her Turn to Talk.

This is why I’ll tell writers that just because Character A asks a question, that doesn’t mean Character B has to answer. They can say nothing and Character A can move on to the next line. At least that way, you’re breaking up SOME of the monotony of the conversation. But outside of a few other tricks, you’re relegated to His Turn, Her Turn, His Turn, Her Turn.

Once you throw this new option into the mix of your protagonist talking to a third person that the second character can’t see, that gives you a rare opportunity to do all sorts of creative things with the dialogue, which is exactly what Bridge does here. I mean you have two characters exchanging dialogue who aren’t even talking to each other. He’s talking to her. She’s talking to us. It’s creativity like this that opens the door for a slew of new options.

The next thing Fleabag does is she talks about things you’re not supposed talk about. Again, this doesn’t come out of nowhere. It’s baked into the character so you have to make that choice early on. But once it’s there, it’s powerful because there are very few things left that are taboo. And the fact that Fleabag consistently finds the taboo subject and talks about it so openly provides something very rare in movie and TV dialogue, which is that you don’t know what the character is going to say next.

You know how in 90% of movie conversations, you can approximately predict what the next line is going to be? Those moments never happen on Fleabag. You’re always unsure of what she’s going to say next and that’s a major key to keeping people watching. As soon as audiences figure out what’s coming next, what’s their incentive to continue?

I don’t want to overlook the technical side of dialogue here so I want you to go back to the first page and reread Fleabag’s opening monologue. Notice that IT’S ONLY ONE SENTENCE. It’s not grammatically correct. It’s not aesthetically perfect. It’s a big messy run-on sentence. However, it fits the character and it fits the situation. She’s someone who rambles on, especially when she’s drunk and horny. If this monologue had been broken into four proper sentences, it wouldn’t have felt right.

Finally, the dialogue is honest and authentic to the character who’s speaking. It isn’t movie-logic dialogue where the writer is attempting to imprint their cool lines or relevant thoughts onto the character. “But you’re drunk, and he made the effort to come all the way here so, you let him.” I don’t know a lot of writers who would be willing to go to this place. It’s borderline uncomfortable to hear. But that rawness, that realness, is what makes it authentic.

One of the best ways to study dialogue is to find a scene that has good dialogue then imagine what the scene would’ve been if written by an average writer. Because those are the scenes I read thousands of times over and have become bored by.

I mean think about how many scenes have been written where a guy or girl comes over for a booty call. Now try and think of any that are as good as this scene. Go ahead. I’ll wait. It doesn’t matter. You won’t find one.

I bet you the scenes you tried to find have the obvious funny initial text exchange. Maybe some clever quip about boning. Cut to the guy showing up. There’s some drunk dialogue. Then they smash. It’s just so… predictable.

When you can take that common of a scenario and twist it into something we’ve never seen before, that’s what’s going to set the stage for a good dialogue exchange. Because you can only do so much with the standard setup.

To summarize everything: First we have a dialogue-friendly character. Fleabag says whatever she’s thinking. She has zero tact. Next, the fourth wall option provides an opportunity for dialogue creativity. This makes the scene read different from what we’re used to. The dialogue is risky in places. It’s authentic to the main character. And, overall, there’s a desire to explore and be playful. You’re not going to find good dialogue the way you find a good plot. You have to be more open and relaxed and allow the words to flow through you. If you try to control them or you try and logically build a great dialogue exchange, it’s not going to work. Conversation is often illogical.

It’s funny. Despite Hollywood universally agreeing that Bridge is an amazing dialogue writer, whenever I post one of these breakdowns, there are always commenters who scream out, ‘THIS IS THE WORST DIALOGUE EVER, CARSON! YOU’RE WRONG.’ I welcome these comments. I only ask that you back up your claim. Give us some analysis on why the dialogue is bad. Dialogue is always one of the more polarizing screenwriting topics so I expect some fiery debates.