Write dialogue like this guy!

Write dialogue like this guy!

The bulk of the Scriptshadow Dialogue book is written. The one chapter I’m still working on is this chapter I’m tentatively titling, the “verbal arena.” This is the chapter that’s going to teach you how to write like Tarantino, Woody Allen, Diablo Cody, Aaron Sorkin. I know some of you will scoff at this but that’s my goal. Sure, I can’t make you as good as those writers. But I can give you the tools to get a lot closer to them than you are now.

So, I’ve been watching a lot of “verbal arena” movies – flicks where the dialogue is inventive and fun and memorable – trying to decode that unique dialogue Matrix within. The other night, I watched Barry Levinson’s, “Diner,” which I hadn’t seen in 20 years and didn’t remember well. But I’ve heard a lot of people talk that movie up as an example of great dialogue.

Man, I have to say, I was really disappointed. Outside a couple of minor exceptions (“Where’d you get this attitude?” “Borrowed it. I’ll have it back by midnight.”) it was mostly mundane middle-of-the-road conversation. I *was* shocked when I realized just how much Swingers borrowed from the film. But, other than that, it was an average movie with, maybe, slightly-better-than-average dialogue.

At that point I was going to go to sleep but then I remembered a script whose dialogue had always impressed me and decided to bust it open and read a few pages to see if I still felt the same way. The script is called “Daddio.” It was a high ranking Black List script from five years ago.

Let me tell you: I’ve been reading A LOT of dialogue over the past few weeks — from amateur scripts, to pro scripts, to pantheon level classic movie scripts — I’m not exaggerating when I say the dialogue in the first ten pages of this script blows almost all of those scripts away.

So much so that I’m going to spend the next few days ONLY diving into this script and trying to figure out what Christy Hall is doing that makes her dialogue so good.

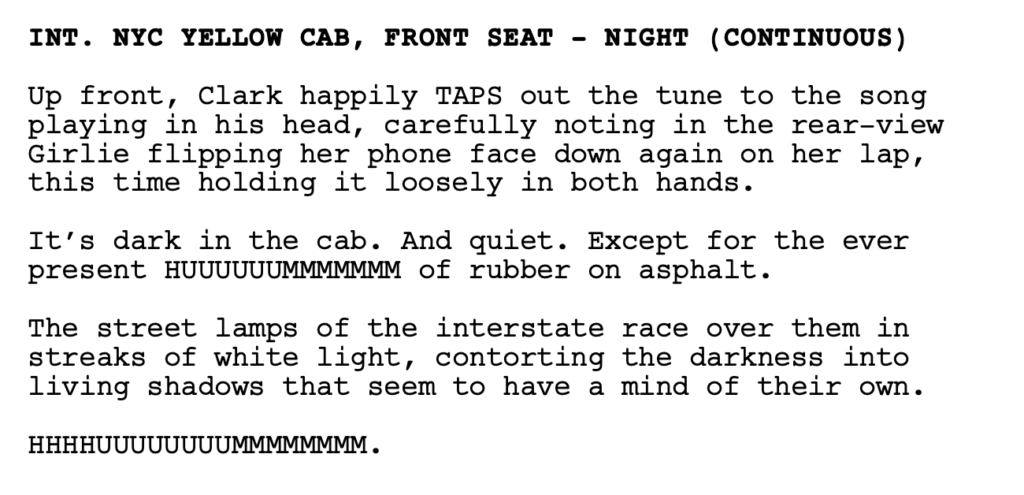

Now, the scene that I’m about to show you is a little different in that it’s more a monologue than a dialogue. But it’s so good I think it’s worth highlighting. In the scene, our main character, Girlie, has just landed at JFK airport, and is going to meet a guy who, from the limited text messages we’ve seen between the two, doesn’t seem all that into her, which is something she’s trying not to think about too much.

The cabbie guy becomes a temporary distraction from this potential down-the-road problem. The script takes place entirely in the cab as we ride from JFK to this guy’s place. It’s one long conversation. What we’re seeing here is the beginning of the conversation.

The first thing you want to pay attention to here is the organic nature of the conversation. This isn’t a “normal” scenario. For example, this isn’t two people waiting at a valet stand for the valet to pull their car up. It’s a long cab ride. There’s a lot of down time involved. Conversations are different in down time. They’re not as immediate or necessary. People are more likely to ramble, which is why this scene works, whereas, if it were at the valet stand, a long philosophical rant about rideshare apps taking over the world would feel try-hard.

My point is, know the situation in order to know what kind of dialogue you can use. The rambling nature of this dialogue works because it’s organic to the situation.

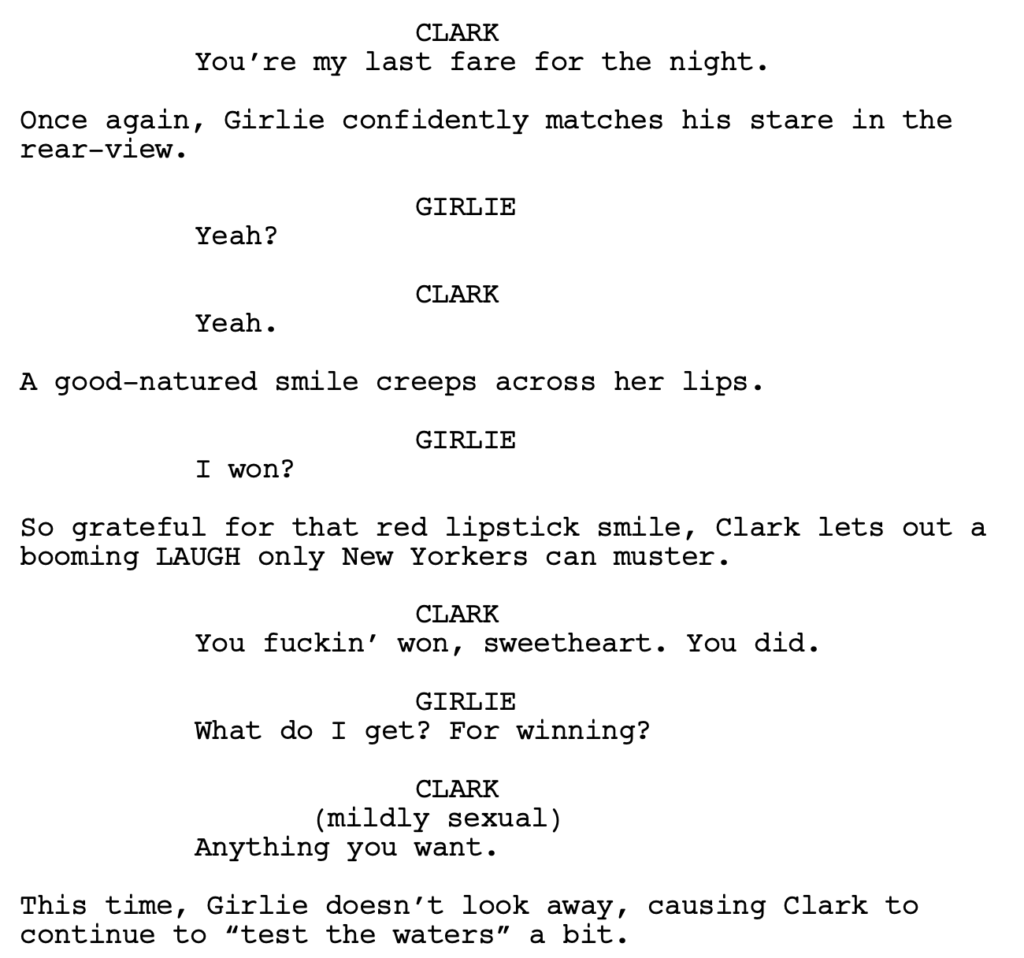

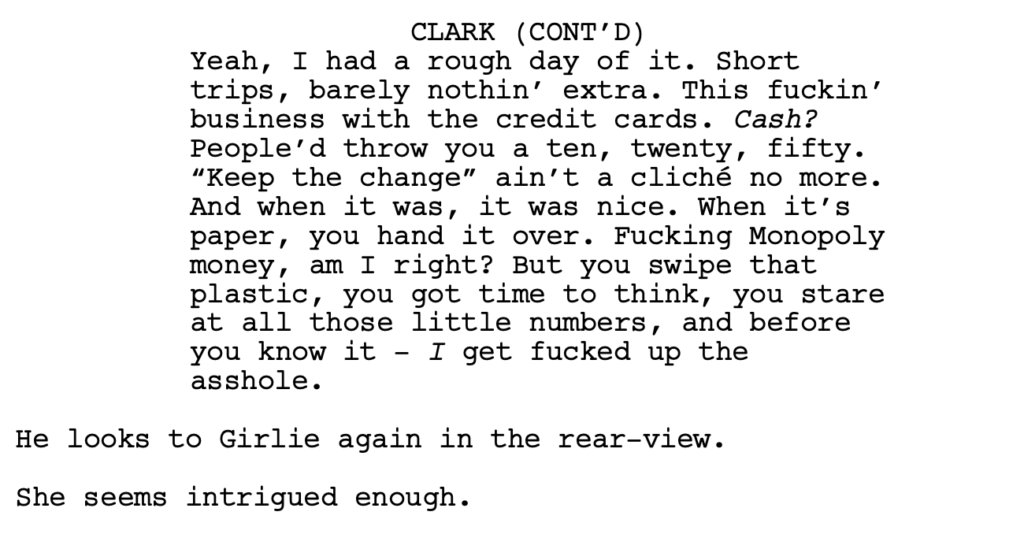

The first segment of Clark’s dialogue is the most “normal.” It’s a guy talking about how his day sucked, he didn’t get a lot of good fares, and he’s unhappy about this payment switch to credit cards cause he makes less money on it. Most writers could write this segment. Although, I thought the “Monopoly money” choice was thoughtful. More creative than saying, “Cash.” Look for these little opportunities to replace standard words with something more imaginative.

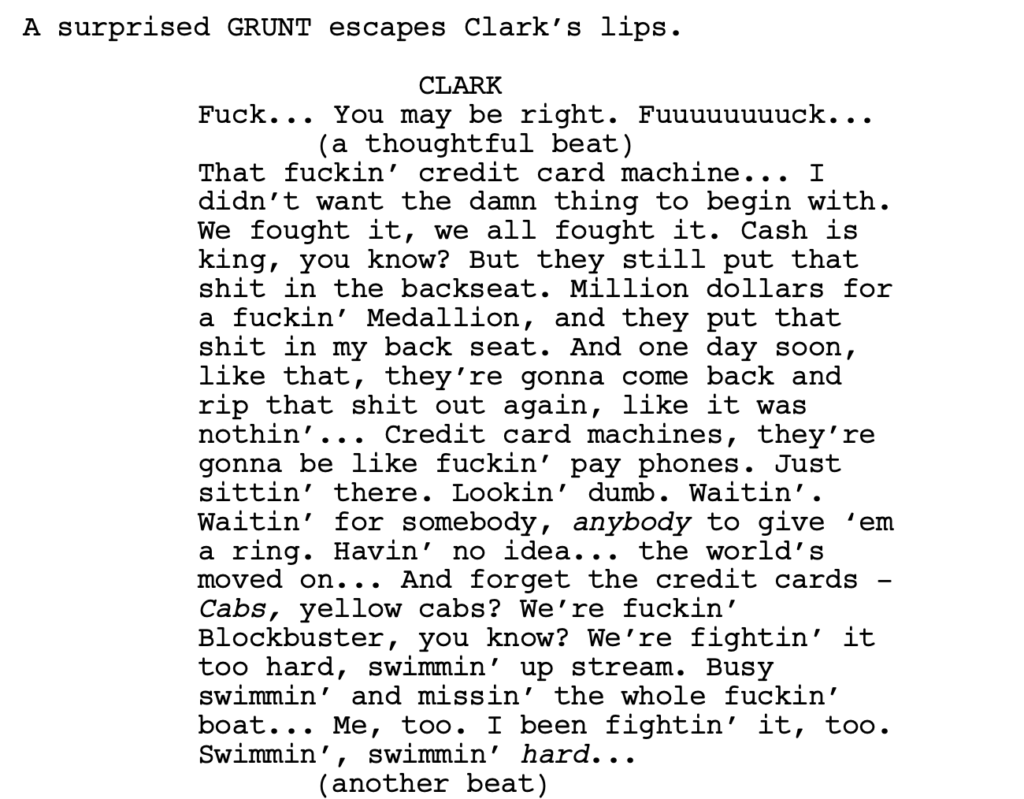

The second segment, however, is where Hall starts to take off. She’s in a triple-7 and everyone else is putt-putting around in a Mini Cooper. Quite frankly, it makes me jealous. Usually, when I read dialogue, I can break down what the writer is thinking and how they crafted the scene to make the dialogue work. But here, there’s so much going on, it’s impossible to keep up.

I like the exaggeration and specificity after the mention of the word “app.” It isn’t just, “These f#$%ing apps are making my life miserable.” It’s, “And now, these f@#%in’ apps, all of ‘em – can get a cab, a coffee, burger, soap, socks, wine, water, Chinese f@#%in’ take out – you can get all that s@#t, and not even reach for your purse, not once, not even for tip.”

Reeling off a number of items drives home the reach of this emerging “app world” Clark hates so much.

From there, the monologue accelerates even more. I’m noticing that in “verbal arena” writing, writers use a lot of metaphors. A metaphor takes an object or action and compares it to something familiar but unrelated. “Charles was a fish out of water.” “Love is a battlefield.” “Life is like a box of chocolates.”

Good writers don’t just use quick familiar metaphors. They take those metaphors and play with them. They extend them (which is why this device is known as an “extended metaphor”). That’s a big part of what’s going on in this scene. Our cabbie character is obsessed with this idea of “the cloud,” and how everything goes up into the cloud. But instead of solely treating the cloud as the technical thing that it is, in this case, it’s used as a metaphor for a real cloud. And what happens when real clouds get full? They start raining.

Hall also intermittently uses something called “personification.” This is when you take a non-human object and you give it human traits. “That big f@#%in’ cloud, thinkin’ it knows better. Swearin’ it can keep a secret.” Then later: “they’re gonna be like f@#%in’ pay phones. Just sittin’ there. Lookin’ dumb. Waitin’. Waitin’ for somebody, anybody to give ‘em a ring. Havin’ no idea… the world’s moved on.”

Another device Hall uses is something I call the “history lesson.” It’s when a character will bust out some historical story or fact that teaches the reader a little something and adds variety to the monologue. We’re in the present and then – BAM – we’re in the far-off past.

“I mean… Salt used to be money. Mother fuckin’ salt. The same shit you sprinkle on your eggs. Yeah. Every mornin’ you toss that cheap-ass-shit all over your eggs with no idea that people used to die for it. Tea, coffee, same thing. All that shit you gloss over at the grocery store, at one point in time, humans fuckin’ killed each other for it.”

This moment in the monologue is important to highlight because I don’t think 99% of writers would’ve written it. Why go off on that tangent when you can be more succinct? But that’s who this character is. He’s a tangent guy. So you want him to go off on a lot of tangents.

Hall then writes my favorite line in the monologue: “Little numbers on a screen. You can’t touch it or hide it or bury it. Nah, you just tie it to a fuckin’ butterfly and send it to that cloud up there.” I have no idea what the device is here or how Hall came up with this line. It seems to be pure imagination, the writer’s own creativity. She could’ve easily written, “You can’t touch it or hide it. It’s just up there in the cloud, hovering.” Not nearly as imaginative.

I like how she also uses adjectives to spruce up, otherwise, bland objects: “But, one of these days, I’m tellin’ ya, that cloud’s gonna open up and it’s gonna pour acid rain down… all over our dumb faces.” It’s not “rain.” “Rain” is way too bland. It’s “acid” rain. It’s not “our faces.” “Our faces” doesn’t tell us much. No, it’s our “dumb” faces.

At every opportunity, Hall is looking to turboboost her sentences. She’s using every pixel to weaponize these words so that they have impact.

From there, she continues to use metaphors to make the dialogue more interesting. “We’re f@#%in’ Blockbuster, you know?” And, “We’re fightin’ it too hard, swimmin’ up stream. Busy swimmin’ and missin’ the whole f@#%in’ boat… Me, too. I been fightin’ it, too. Swimmin’, swimmin’ hard…”

The biggest lesson to take away from today’s dialogue example is metaphors. A lot of the color from this dialogue comes from Hall repeatedly dipping into metaphors. Yes, there’s more going on. But if you try to ingest it all, I’m afraid it will be too much. Just start to look for ways to incorporate more metaphors into your dialogue. Make sure you’re doing so in an organic way. And try to play with them a little bit so they’re not cliched metaphors. You don’t want to say things like, “Flying off the handle” or she has a “heart of gold.” These are actually referred to as “dead metaphors” because they’ve become so overused. Try to come up with your own metaphors and then extend (play with) them.

Here’s the screenplay for Daddio if you want to see more of Christy Hall’s writing. Leave your thoughts about what else she’s doing right in the comments. And, if you disliked the dialogue, tell us why.

GET A SCRIPTSHADOW SCREENPLAY CONSULTATION! – As much as we writers think we can do it alone, we need help. We need fresh eyes on our material. Without that, we can’t identify the problems in our scripts. We won’t figure out where we need to improve as a screenwriter. I’ve read over 10,000 scripts. Done over 1000 consultations. I am the guy who can figure out the issues hampering your script AND HELP YOU FIX THEM! I have a 4 page notes package or a more detailed 8 page option designed to exponentially improve your screenplays. I also give feedback on loglines (just $25!), outlines, synopses, first acts, or any aspect of screenwriting you need help with. This includes Zoom calls discussing anything from talking through your script to getting advice on how to break into the industry. If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s set something up!