I had a giant screenwriting revelation this week.

Anybody who’s gone through a good revelatory moment knows that it’s exciting but also terrifying. Terrifying because any new revelation strips down at least part of your belief system. It forces you to rethink everything. And this one, this one I was sure I knew how to do right. Now, I’m not so sure.

How this came about is that I was reading a few screenplays for the contest and they were all really boring. Not bad, mind you. But boring. Bland. Lifeless.

What makes a script boring? A number of things. But the primary one is that the story is predictable. We’re always ahead of the writer. The reason so many writers, both amateur and professional, write these boring predictable scripts is because they map out the story from start to finish. They then go in, follow the map, and because the route has been so carefully planned ahead of time, there is no spontaneity to the story. There are no unexpected twists (except for blatantly manufactured ones – “the agent’s handler is actually the villain!”). There are no surprising developments. How could there be when you’ve constructed a series of events that are a carbon copy of events from movies we’ve already seen?

I began to think, what’s the problem here?

Why do I read so many scripts that have this issue? And why are writers so blind to it?

And here’s where my revelatory moment came.

It’s because too many writers know their ending before they start writing.

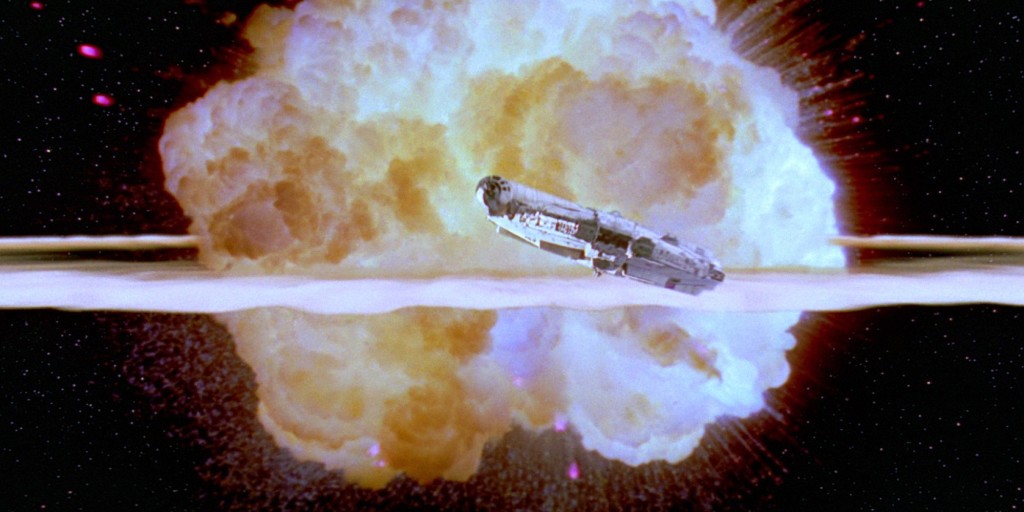

You’ve heard me espouse before not to start your screenplay until you know your ending. The advice sounds good in theory. If you don’t know where your script ends, how do you know where to place your characters in the meantime? Knowing your ending allows you to come up with a clean goal-driven narrative. Luke Skywalker blows up the Death Star. Okay. Now I just have to come up with the story that gets him to a point where he has the opportunity to blow up the Death Star.

However, here’s the catastrophic problem with knowing your ending before you begin.

If you know where you have to deliver your character, you will never put them into any situation that will seriously impede your ability to deliver them there.

For example, a couple of weeks ago, I reviewed a script called Video Nasty about a brother and sister who get stuck inside a horror movie. The script was okay. I think I gave it a low ‘worth the read.’ But it wasn’t memorable by any means. And a big reason for that is this problem. The writer knew, before he started writing the script, that the brother and sister were going to escape the movie and be okay at the end.

So let’s say, midway through writing the script, around the midpoint of the story, the writer thought to himself, “Man, it would be really great right here to kill off the sister. It works thematically and it will shock the audience.” But he can’t do that. He won’t do that. Why? Because he has it locked into his head that the brother and sister get out at the end. So, instead, he writes a scene where the killer corners the sister in a house and almost kills her but she gets away. The scene is average because it’s handicapped by that locked-in ending. We can’t put her in too much danger because then my ending is compromised!

Now let’s say the writer went into the script NOT KNOWING the brother and sister get out at the end. In that situation, he is more likely to follow his gut when writing. He’ll kill off the sister and figure it out later. Also, because his brain is open to any possibility, he may figure out a way to bring her back from the dead! If the brother and sister are stuck in a movie, and movies aren’t real life, then a death may not be a death. Now maybe he figures out a way to bring the sister back or maybe he doesn’t. The point is, he’s created a less predictable story this time around because he’s not beholden to that set path.

As I delved deeper into this, I realized it extended beyond the ending. If you figure out your midpoint ahead of time. If you come up with some major twist you want to happen at a certain page. You will now be writing towards those moments, and, without realizing it, creating predictable mini-narratives. Once you determine any outcome, you’re never going to write anything that steers you too far away from that outcome.

All of this led to the realization that, oh my god, knowing your ending is creating an endless stream of predictable screenplays! Even worse, any exercise that sets checkpoints in stone – such as outlining – is a creativity killer! They keep the script on the road when everybody knows the best moments always happen when you go off-road.

However, here’s why it’s not so simple. Not knowing anything that’s going to happen in your script is just as bad. It creates a different type of problem. Without outlines, writers lose steam around the 45-page mark. It’s hard to make something out of nothing for 110 pages straight. You need SOME direction or your script becomes a rambling mess.

I can’t stress that last point enough. The unstructured equivalent of the “bland predictable screenplay” is the “rambling unfocused mess of a screenplay.” If all you’re doing is writing whatever comes to mind in the moment, your script comes across as disjointed. Mank is a good example of this. It starts out about a guy trying to write a screenplay and ends up being a political film, likely because Jack Fincher thought, “This screenwriting storyline is fun but I want to go explore this other thing now.”

Which leads us to the obvious question – What do we do about this???

I have two options for you. It comes down to what type of writer you are. Do you need structure to operate or not?

If you’re comfortable writing without knowing how your story ends, or even where it’s going to be in thirty pages, go ahead and write that way. You’re way more likely to find interesting story directions than the restricted writer. Your script is going to be less predictable and, therefore, more compelling. However, you’re going to have to do twice as many rewrites as the structured screenwriter. That’s because your narrative is going to zig-zag so much that it’ll take more time to eliminate the ideas you came up with that don’t work. And for the ideas that do work, you’ll have to go back in your story and set them all up. For example, if, like in Parasite, you came up with this on-the-spot idea that another family was living in a secret basement in the house – you can’t just throw that one in there with no explanation. You’ll have to write in hints here and there that the basement exists so that its eventual reveal is a payoff (as opposed to one of those random doesn’t-make-sense-at-all reveals you see in so many amateur scripts).

If you’re a structure person and your beat-by-beat outline is your childhood blankie and you won’t dare start your script until you know your ending, that’s fine, too. You can continue to write this way. However, you have to embrace a different psychology when you write. When inspiration strikes, follow that inspiration, even if it goes against your outline. Also, and this is even more important – you must learn the art of painting your characters into corners that you have no idea how to get them out of. The reason this is so important is because your default style of writing is predictable. In the past, that’s what’s caused you to make sure there’s always an air conditioning vent right above the corner you’ve painted your character into. You’ve created the escape plan before you’ve written the scene. And when you do that, the reader gets this feeling that the outcome has already been decided. Which saps the life from a scene. You want them thinking the opposite. “Oh my God, how are they going to get out of this?” The only way to achieve this is if you genuinely have no idea how you’re going to save your character. If you take nothing else from this article, take that. If you become an expert at that skill, you’ll write tons of captivating scenes going forward in your career.

I’m curious to hear what your responses are to this realization because I definitely think a script has more energy when even the writer isn’t sure where the story is going next. Which makes sense. If they’re not sure, how can you possibly be?