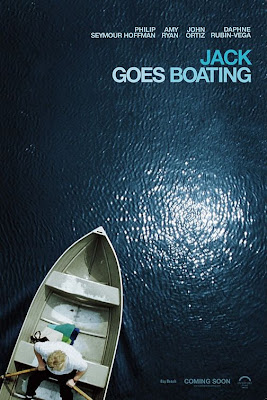

Genre: Indie Drama

Premise: An emotionally reserved limo driver is introduced to an emotionally imperfect woman, which results in a slow courtship.

About: This is Philip Seymour Hoffman’s directing debut, which premiered a few weeks ago at Sundance. Hoffman also stars in the film alongside Amy Ryan. Apparently Hoffman feels the need to spread his wings, as he recently started his own production company, “Cooper’s Town Productions,” with Emily Ziff. The company’s initial slate includes a thriller with Guy Pearce and Mary-Louise Parker titled, “The Well,” as “well” as the Hoffman starrer “Mr. Crumpacker and the Man From the Letter.” Robert Glaudini, the writer of “Jack Goes Boating” is an actor who’s appeared in such films as “Mississippi Burning” and “Bugsy.” He wrote “Jack Goes Boating” as a stage play, which Hoffman ended up starring in. The off-broadway production received great reviews, and Hoffman hired Glaudini to adapt the play into a screenplay.

Writer: Robert Glaudini (based off his own play)

Details: 115 pages (1/28/09 draft)

The biggest clue about what to expect with “Jack Goes Boating” is that Jack never actually goes boating. Jack never really goes anywhere for that matter, and if you don’t like your independent entrees served slow and cold, you may want to set sail for another pier.

There are always challenges inherent in adapting a stage play to the screen , and the biggest of them is obviously opening the story up. Since plays require limited characters, limited locations, and limited scope, jumping from stage to screen often feels like a bachelor moving into a mansion. How do you use 50 rooms if you only need two? The wonder of film is its ability to take us anywhere in the universe. So if our characters are stuck in a couple of living rooms and a back alley, there better be a damn good reason for it, or else we’re going to get bored quickly.

Jack Goes Boating definitely suffers from this problem of Limitednus Maximus. While there’s some meaty emotional issues for the actors to play with, the story itself embraces a simplicity that calls into question the very existence of a plot. Guy tries to court girl. That’s it. Now each of the characters is fucked up and weird, which spices it up a little, but this isn’t something you want to read right after checking your Twitter Feed for an hour. Some mean patience is required.

Jack is a New York limo driver who spends the majority of his free time digging the smooth sounds of Reggae. Since there’s no real future in limo driving, Jack dreams of bigger things, such as…. a career in the MTA (the transit management business). Not quite sure why he thinks this is an upgrade but then again, Jack’s not the kind of guy that makes a lot of sense.

Jack’s best friend is his co-worker, even-keeled Clyde, whose relationship with the beautiful but feisty Lucy is the kind of thing he wouldn’t mind having for himself. Lucky for Jack, Clyde’s got an idea. They have a mutual friend named Connie who’s an embalmer at a local funeral home and they would luurrve to set them up on a blind date. Jack’s hesitant because an embalmer has to be the one job that would attract a person even more reclusive than himself, but in the end he goes along with it.

Connie is like a stranger version of Talia Shire’s “Adrian” character from Rocky. She’s so bizarrely introverted that she’s almost incapable of human conversation. Jack’s no Lothario himself though, so their banter is a lot like listening to a dying turtle converse with a homeless man. At the end of the date, Connie invites Jack on a second date – to go boating. There’s only one problem. It’s the middle of winter. So a boating date wouldn’t happen for six months. Jack’s not sure if that means he can see her before then or if he’s supposed to wait until summer. And since neither of them is capable of a basic question followed by a simple answer, the mystery cannot be solved the way it would with 99% of the rest of the population.

Clyde and Lucy act as professors of protocol though, encouraging the two to keep seeing each other, despite how awkward and strange each of these meetings is. Eventually they agree on a second “official date before the boating date” that will include Jack cooking dinner for everyone.

In the meantime, Jack is horrified to learn that Clyde and Lucy, his only template for the world of relationships, aren’t as happy as he assumed. It appears that Lucy’s had several affairs during their time together, and Clyde can’t block them out anymore. Jack finds himself in the unlikely position of giving advice instead of taking it, and since he’s about as equipped to do that as a street vendor is to give stock tips, Gary’s relationship dissolves right before his eyes, even as his own relationship begins to bloom.

Jack Goes Boating was a tough read. The main issue here is the pacing, which is so slow at times, I thought I was in a doctor’s waiting room. This is actually something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately – this “slow burn” approach to a story. It’s not a bad thing . Each film has its own pace. But how slow is too slow? Because I’m wondering if readers hit a point where they’re simply unable to enjoy a slow screenplay. It would make sense. Your threshold for patience is at a constant low, and that may be why the only specs that sell these days are ultra-fast move-move-move stories (Check recent sales “Safe House” and “Abduction”).

But I liked Revolutionary Road, and that script is about as slow as it gets. So this is the conclusion I came to: The slower your script is, the more dependent you are on the reader being interested in your subject matter. The degradation of a relationship is a fascinating theme to me, which explains why I liked “Road” (where I know many hated it). But had that script been the exact same pace with the exact same characters, except now they were, say, turning into vampires, that glacial pace probably would’ve been the last straw. That’s why an up tempo script is preferable if your story can handle it. Make a few more things happen. Stuff a little more into the story. Add a few more twists and turns. Information needs to come at the reader faster. You can essentially tell the same story you want to, but packaged in a way where it will appeal to a wider audience. What’s wrong with increasing the chances of your script getting sold?

Now for the very reason I mentioned above (in reference to the relationship in Revolutionary Road), I enjoyed watching Clyde and Lucy’s relationship crumble towards the end. But that led to a whole nother set of problems – namely that I never felt like I knew Clyde and Lucy, and therefore could only get so invested in their late-story problems. As a result we’re left with Jack and Connie, and while I cheated and imagined some great chemistry between Hoffman and Ryan on screen, the truth was reading them on the page wasn’t very interesting. I was hoping for more.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

For a review of the movie, head on over to Movie Jungle.

What I learned: I’ve said this before but I’ll say it again. “Real life” doesn’t exist in 2 and a half minute segments. So if you try and shoehorn a real-life conversation into your screenplay under the guise that it will make your characters and story feel more authentic, you’ll find that your characters don’t sound quite right. Sure, you’re getting that “real life” feel, but listening to two people talk in real life is often boring and pointless. So your scene, not surprisingly, feels…boring and pointless. In screenwriting, you want to have a point to the scenes you write. You want each character to have a goal. You want their conversation to move the plot along. You want some conflict to be involved. The less of these things that are going on, the more boring your script is going to read.