So maybe I was a little bit of an ageist yesterday. Picking on a script because it was written by a 22 year-old. The script had made mistakes, I claimed, that only a young writer would make. That was some proper-ass stereotyping I was doing. That’s not cool, Carson.

But it was true.

In revisiting my Maximum King reading experience, I further realized why the script had missed the mark. It was completely devoid of any conflict. The reason that tends to be a young writer mistake is that younger people haven’t experienced the pushback from life that a longer living experience gives you. You don’t truly realize how difficult life is until you’re thrust out into it and it does everything in its power to beat you down.

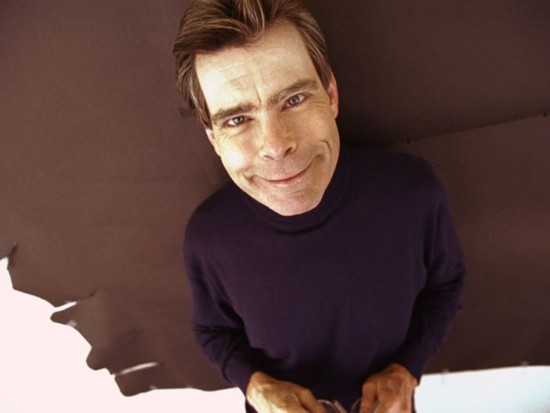

From the very first scene in Maximum King, conflict appears to be an afterthought. Someone comes to Stephen King and says, “Do you want to make a movie?” To the uninitiated screenwriter, you look at that and go, “So what?” To people who understand drama, they know that that’s the worst way you could possibly start a story. One of the most sought after and hard-to-get jobs in America – directing a movie – is just HANDED to our hero?? He didn’t have to do anything for it but exist??? That’s not drama. That’s boring.

But I’ll give you the moment that confirmed to me that this screenplay was screwed. I knew after this scene that the writer didn’t understand the concept of conflict. And since conflict is the whole ball of wax in screenwriting, the future looked grim.

The scene in question has Stephen King deciding he wants to hire AC/DC to score his movie. Why? Because they’re his favorite band. Had they ever scored a movie? No.

You would think, then, that this would be the perfect opportunity for conflict. Stephen King goes to his heroes, asks them to score his movie, and they say “No. We’re not movie composers. We’re a hard rock band. Go fuck yourself.” And Stephen King would then have to CONVINCE them to do it. The scene almost writes itself.

Instead, we get this…

“So you want us to—“

“Write an original soundtrack for the movie, back to front, yes.”

“And the movie is about—“

“Right, trucks— no, well, not just trucks but all machines, because a comet passes over Earth and causes all the machine to—“

“Sure, come to life.”

“Exactly.”

“Well shit, I guess I’m the fuck on board. I love your writing, and Brian is a huge fan of Carrie, so.”

Brian agrees.

“Great.”

“Great.”

Do you see how boring that scene is? Do you see how it could’ve potentially been a lot better had they told King no? I mean that early line is practically begging for a no. “And the movie is about…” “Right, trucks— no, well, not just trucks but all machines, because a comet passes over Earth and causes all the machine to—“ Long pause. “Dude, that doesn’t make any fucking sense. How the hell are we supposed to write music to that?” And King now has to convince them.

Nope. Didn’t get that.

So that’s today’s lesson. It’s simple yet powerful.

JUST SAY ‘NO’ TO YOUR HERO

Your protagonist will want a lot of things in a movie. He might want a raise. He might want sex from his wife. He might want to sell milkshake makers to fast food restaurants. He might want more attention from his parents. He might want to go with his dream girl to prom. He might want to explore an island he believes contains a giant ape. He might want his daughter to start eating dinner with the family again.

Say no.

Have all those people say no to your hero.

Because when you say no, that’s when things get interesting. That’s when your character has to work for it. And work means action, which leads to uncertainty, which leads to audience curiosity (“Is he going to succeed or fail!?”). And that’s when you’ve got us. Cause we have to stick around to see what happens.

The second someone says, “Yes?” None of that can occur. There’s no uncertainty at all. And that’s boring.

It should be noted that I’m not just talking about LITERAL “No’s.” I’m talking “no’s” in every form and fashion. An open door is a ‘yes.’ A locked door is a ‘no.’ An equation solved quickly is a ‘yes.’ An equation your hero can’t figure out is a ‘no.’ A surgery that goes well for your hero is a ‘yes.’ A surgery that goes badly, setting your hero back, is a ‘no.’

Your screenplay should be one giant series of “NO’S.”

I challenge you right now to go through your current screenplay, find a scene where your hero is allowed to waltz right through without any issues at all, and instead, add a “NO” to that scene. Throw a big fat hard NO into his face and make him work for that objective. I guarantee you the scene gets a lot better.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations, which go for $25 a piece of 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!