Genre: Holiday

Premise: An old miser of a man is visited by three ghosts on Christmas Eve who place him on the path to finding happiness again.

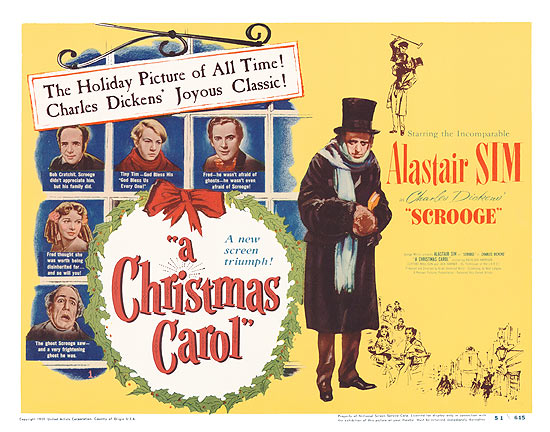

About: Charles Dickens is the original author of A Christmas Carol, which he wrote as a novel in 1843. It has since been adapted into a movie nearly 50 times, starting all the way back in 1901. Today I’ll be reviewing the 1951 version of A Christmas Carol (titled “Scrooge” in the UK) as I believe it’s the best of all the adaptations. The writer of this adaptation, Noel Langley, may sound familiar. He adapted The Wizard of Oz as well.

Writer: Noel Langley (original author of book: Charles Dickens)

Details: 86 minute running time

MERRRRRRY CHRISTMAS EVERYONE

It’s time to open your presents, drink your eggnog and be told by your parents that you’re not doing enough in your life. It’s the Christmas way!

I’m always fascinated by movies that stand the test of time. Of everything out there, these are the films you need to study most. With 99% of movies forgotten within a month of viewing, the stuff that lasts obviously has some secret sauce in it, something you can extract to apply to your own screenplays.

A Christmas Carol has lasted for over 150 years. That means it’s lasted through two world wars, Billy The Kid, a trip to the moon, the Civil Rights movement, the invention of the internet, and even Justin Bieber. In a society so finicky, so obsessed with the next big thing, how is it that A Christmas Carol has stuck around?

You may say, “Oh, well, it’s a Christmas movie. Since Christmas comes around every year, it has an advantage.” Not true. Christmas movies are easily some of the worst movies ever made. They’re probably the hardest “genre” to get right. If anything, that’s working against the film.

I watched “Carol” again this year and it hit me the same way it did when I first saw it as a kid. The difference was, this time, I figured out HOW it was able to do this. I figured out its “secret sauce.” While the answer to its success may not surprise you, you will be surprised at just how simple it is.

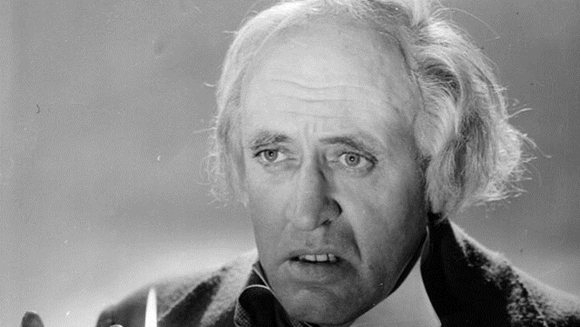

For those who don’t know the story of A Christmas Carol, it follows the most selfish, nasty, heartless man on the planet, Ebenezer Scrooge. A Christmas hater, Scrooge finds himself being visited by three ghosts on Christmas Eve, the ghosts of Christmas past, present, and future. It’s through this journey that Scrooge remembers the joys of life and how important it is to help and be good to others.

One of the most perplexing things about A Christmas Carol is that it flies in the face of everything we’re taught about a leading character. We are told that our hero must be likable, someone an audience can root for. Scrooge is probably the most unlikable person you’ll ever meet. When told that someone he knows might die, his response is, “Hurry up so we can decrease the surface population.”

I wouldn’t classify Scrooge as a hero. I wouldn’t even classify him as an anti-hero. Scrooge IS the villain of this story. And yet he’s our main character. Every screenwriting book and producer in Hollywood would tell you that that’s a surefire way to ruin a screenplay.

While many would use this as fodder for their belief that Hollywood is run by idiots, I’ve actually read far more scripts where an unlikable protag doomed a script than I have asshole heroes making a script better. So why does it work here?

My guess is that we move into the potential for change pretty quickly in A Christmas Carol. There are maybe seven scenes (some of them very short) before Scrooge is visited by his old partner, Jacob Marley, and he’s placed on the path towards change. Were we stuck with this guy for half a screenplay before he was taken on this journey, I’m sure we would’ve been less forgiving.

Another interesting aspect of A Christmas Carol is its structure – or, more specifically – how it lays out its structure for the audience. We’re told, within 15 minutes, that three ghosts are going to visit Ebenezer Scrooge, essentially giving us an outline for the film we’re about to watch.

Many writers assume that if you tell your audience what’s coming, the story will be predictable and boring. But actually, the opposite is true. By telling the audience what they can expect, you have a direct line into their expectations (since you’ve created them!), which means you can now play with them. You can zig where they expected you to zag. You can twist when they were sure you were going to turn. This approach gets great results since the reader is constantly trying to outguess the writer, and if you’re doing your job, you (the writer) are always winning.

But let’s get to the nitty-gritty. The “secret sauce” of A Christmas Carol and why it’s lasted as long as it has. Why generations of children grow up, just like their parents, falling in love with the film and its main character. Are you ready? Care to make any predictions? Okay, here it is:

A Christmas Carol is a deep-set character exploration disguised as a film.

We have ghosts here. We have time travel. We have flashy larger-than-life characters. But this isn’t about that, is it? A Christmas Carol is about one man’s transformation from a cruel selfish person to a selfless happy one. Everything that happens in the movie is built around that transformation.

I can’t stress this enough. So many movies we watch these days are obsessed with the spectacle. And then, because the writer was told to do so by a screenwriting book, they half-heartedly add a few beats to their story about their hero changing. You can smell these scripts from a thousand miles away. The writers don’t WANT to transform their hero. They don’t care about developing the character or arcing them. They do it because they’re told to.

A Christmas Carol IS its character development. It IS its hero’s transformation. Each trip on this journey is Scrooge being forced to examine himself. This is why A Christmas Carol is as timeless as it is. Because spectacle always dies. A chase scene, as awesome as it might be, is a technical achievement at best. But seeing a person come to terms with who they are, and to then transform and change into a better person – by golly that hits us where it counts. Because WE want to change. WE want to become better people.

Ironically, this goes back to my earlier observation. None of this transformation – none of the very thing that makes this movie so timeless – is possible without starting off with an unlikable protagonist. If you had tried to give Scrooge a “save the cat” moment or offset his cruelty by giving him a mother he cares for at the hospital, the transformation wouldn’t have been nearly as satisfying. This man has to start at -100 or the movie doesn’t work.

So where does this leave us with A Christmas Carol? What can we learn from it and apply to our own screenplays? Well, I always think that the unlikable protag approach is a gamble. It’s not that it can’t work, as we see here. But if you don’t get the character just right, the reader will hate them and not want to follow them. The best advice for those wanting to use an unlikable lead is “proceed with caution.”

The bigger takeaway here is to look for stories that are built around character transformations. As time has proven, these are the stories that resonate with audiences the most. And that doesn’t mean you should be writing tiny indie flicks about characters building sewage systems in third world countries. Far from it. Once again, A Christmas Carol has ghosts and time travel. It’s more about finding an idea that’s conducive to character change. Do that and you might be giving yourself the biggest Christmas gift of all – a great screenplay.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: At least one way to make an unlikable hero bearable is to start their transformation into a better person early in the story. If we see that our asshole protagonist is on a path to becoming good early on, we’ll be more tolerant of their faults.