Genre: Action/Crime/Comedy

Premise: An assassin gets stuck on a Japanese bullet train with several other assassins, all of whom get mixed up in an intense plan by an evil mastermind named The White Death who’s determined to kill them all.

About: The David Leitch directed Brad Pitt starrer, Bullet Train (!) racked up 30 million bucks this weekend. It’s not a ton of money and no doubt they were hoping for something closer to 45 million. But maybe Bullet Train never had the firepower capable of significant box office damage. Here’s my old Bullet Train script review.

Writer: Zak Olkewicz (based on the book by Kotaro Isaka)

Details: 126 minutes (screenplay was 121 pages)

Poster of the year?

Poster of the year?

This is a PANDEMIC SPECIAL.

It was a movie created specifically to be produced during the pandemic. Almost the entire film is shot on a tight movie set (a series of train cars). And you can definitely feel that while you’re watching it. Even when the actors are pretending to be in mortal danger, I don’t think we ever really believe they are.

Bullet Train follows an assassin named Ladybug (Brad Pitt) who’s in Tokyo where his job is to grab a suitcase on a train, then get off at the next stop. Unfortunately, the guys he steals the suitcase from, Tangerine and Lemon, figure out what he’s done before he’s able to get off. So they chase him around the train to steal it back.

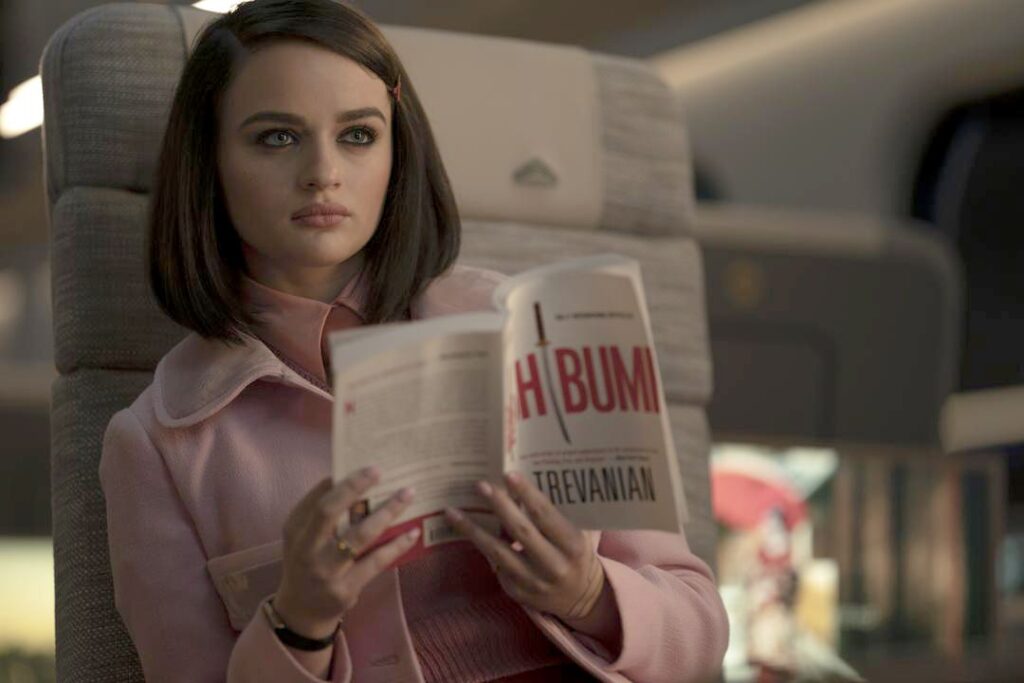

Meanwhile, there’s this psycho teenager girl named Prince who’s zig-zagging around the train killing people for her own nefarious purposes. Her ultimate plan is to assassinate the most fearless killer in the world, The White Death, who’s waiting at the end of the line. As we get closer to our destination, these two storylines – Ladybug’s and Prince’s – intersect, resulting in both needing to take on The White Death together.

Let me help you see just how incestuous Hollywood is.

Back in 1998, a young British director named Guy Ritchie released a cool little crime-comedy called Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. The movie was heavy on over-the-top comedic dialogue, quick cuts, and guns.

The film made Ritchie a known name in Hollywood, which attracted many a movie star who wanted to be a part of his first American production. The actor who won that lottery was mega-star Brad Pitt, who played the character of Mickey in Ritche’s “Snatch.”

As Brad Pitt’s career continued, he would need a stunt double for every project. And the man who became his main stunt double at the time was a guy named David Leitch. Leitch, along with fellow stunt man, Chad Stahlenski, muscled their way into the directing chair after a couple of decades, directing the surprise hit action film, John Wick.

Meanwhile, Brad Pitt, in what would become one of his most memorable roles, played a stunt man named Cliff Booth in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Tarantino, of course, was a gigantic influence on the aforementioned Guy Ritchie.

Cut to last year, when Brad Pitt, he who just played a stunt man for Quentin Tarantino, a major influence on Guy Ritchie, decided to join Bullet Train, a movie directed in the same fashion as a Guy Ritchie film, where he would be directed by David Leitch, a man who, for over a decade, was Brad Pitt’s stunt double.

Crazy, right? What does it all mean?

For starters, it means don’t try to make a Guy Ritchie movie when you’re not Guy Ritchie.

But discussing Bullet Train is actually more complicated than that. This is not a bad movie. It’s not a good movie. It’s a movie that exists. And if you’re like me and into the little details about why a movie works or doesn’t work, this is a fun one to dissect. Because there isn’t any one thing that hurt this movie. Rather, it was a bunch of little bad decisions.

Before we get into the screenwriting stuff, I have to say that choosing to make a comedy when your lead actor is not a comedian, when your supporting cast are not comedians, when your director is not a comedic director, and when your writer is not a comedic writer, probably isn’t the best idea.

Comedy is very hard to pull off. If the timing is off by even half a second, it could be the difference between a big laugh or no laugh. And that was Bullet Train in a bullet shell. The timing on the jokes always felt off. We’re not talking Ben Falcone bad. But the movie felt like an approximation of how an action-crime-comedy should play. It never reached that assuredness that a Guy Ritchie would bring to the party.

But we’re not here for the filmmaking. You can get opinions on that anywhere. We’re here for the screenwriting, baby. And the screenwriting in Bullet Train is a primary example of why flashbacks can be so dangerous.

Flashback is made up of two words.

FLASH and BACK.

“Back,” in particular, is a scary word in screenwriting parlance because stories work best when they’re going FORWARD. Not BACKWARDS.

So if you’re doing something with the word “back” in it, you’re literally going against what makes movies good.

Bullet Train is obsessed with stopping the story and doing occasional little flashbacks where we learn more about the characters’ backstories. In theory, this isn’t the worst idea. The more we know about someone, the more we’ll care about them (theoretically). So I understand the reason for the choice.

But every creative choice has a drawback to it – some bigger than others – and when you’re choosing to flash BACK, the big drawback is that YOU STOP ALL FORWARD MOMENTUM OF YOUR STORY. Believe me, the audience (and the reader) feel this.

My interpretation of how Leitch approached this device was to keep the flashbacks so fast and fun, it wouldn’t feel like the story was stopping. The problem was there were a lot of flashbacks. And, more importantly, they weren’t as cool or as funny as they were trying to be. So because they weren’t working, we felt that narrative stoppage every time a flashback arrived, and because that kept happening, the movie was never able to keep our attention. We were always drifting out then being pulled back in.

Also, when so much of your movie depends on cutesy fun dialogue, you better be lights out at writing cutesy fun dialogue. You can’t be okay at it. Or even slightly better than average, which is where I’d rank the cutesy fun dialogue in Bullet Train. If something is being done so frequently in your screenplay that it’s part of the fabric of the movie, those are the areas you have to nail. And they weren’t nailing them.

Another major error that they made on the screenwriting front was the main character, Ladybug (Brad Pitt).

They never explained him well. Is he a trained killer? Because he seems to be able to kill a lot of skilled assassins. But he acts so goofy all the time that I think we’re supposed to believe he lucks into all of these kills. That they had nothing to do with skill. Which means he’s basically Jar-Jar Binks.

But I was never entirely clear on that. Is he good fighter? Is he a bad fighter who gets lucky? Or maybe he’s a good fighter who no longer wants to fight so he plays defense the whole time? It was confusing, man.

I will say that I liked the decision to use Maria, Ladybug’s handler, as a constant source of voice over. One of the harder things to do in a script like this (with five different assassins all chasing individual plotlines) is keep the audience up-to-date on what’s happening. By creating this handler who calls Ladybug intermittently, she can keep reminding Ladybug (and by association, us) what’s going on and what he needs to do. She can remind him, for example, that he has to get out at this next stop. And it goes both ways. Ladybug can remember out loud to Maria other relevant exposition. “Oh yeah, I remember that guy. He was at the wedding I was at where I killed the bride.”

If Maria is not in this movie, how do we get this information? Ladybug would have to talk to one of the enemy characters about it. Which wouldn’t be believable at all. It can be done, of course. But as a screenwriter, you should always be looking for strategies to attack exposition in a movie that has a lot of moving parts (and therefore will require a lot of exposition). They had a good strategy here.

I also liked the ending more than I thought I would. The movie does such a good job setting up the character of The White Death that we want to see what happens when he shows up.

And remember, whenever you’re writing a movie and you’re unsure about your climax, just go back to your concept. The answer is always in your concept. This movie is called Bullet Train. Therefore, the movie needs to have a big splashy bullet train crash. And they don’t disappoint. If you’ve ever asked the question, what happens to a bullet train when it runs out of track, this movie gives you the answer. I point this out because there was a moment where it looked like they were going to end the movie at the Kyoto stop with a big flashy fight just outside the train. That ending would have been disastrous.

If I had just one word to describe Bullet Train, it would be, “frustrating.” There was definitely a good movie in here, but the decision to turn it into a comedy when nobody involved is known for comedy was kinda fatal. If this were a streaming movie, I’d tell you to watch it for sure. But I can’t, in good conscience, say it’s worth paying for in theaters.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Physical movement is powerful in visual storytelling mediums. If we’re physically moving towards something, it creates the illusion of importance later on since the audience naturally want to see where the movement stops. That’s what kept Bullet Train just watchable enough, was the need to see where the train stopped. But you can do this with characters moving (1917) you can do it with a vehicle (Mad Max). You can do it in a spaceship (Passengers). Movement is typically preferable to stillness in movies. Which should be evident from the word itself – “Movie.” Aka, “Moving.”