Genre: Comedy?

Premise: A racist southerner has a split personality that turns him into a devout liberal named Rodeo Rob, who believes he’s from the year 2525.

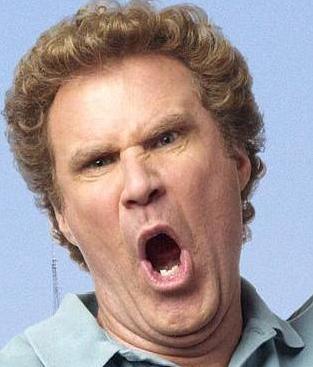

About: Vince Gilligan is the writer of what some consider to be the best television series ever, Breaking Bad. He originally wrote this script back in 1990, and over the years has honed it according to whomever became interested. The closest it got to production was in 2008, when Will Ferrell wanted to star in it. But a director was never found. Says Gilligan: “I don‘t know that the movie will ever get made because at the end of the day, it’s a little bit tricky, because it’s a comedy with the N-word in it.”

Writer: Vince Gilligan

Details: 129 pages! This is the 2008 draft that Will Ferrell was supposed to be in.

Chalk this one up to “What the fuuuuuuuuuhhhhh?”

I don’t know what I was expecting when I opened an early script from Breaking Bad’s Vince Gilligan, but I sure as hell didn’t know it would be this.

On the one hand, this is what you want from a writer – a script that actually takes some chances. But boy, I mean, at what point have you traversed so far off the reservation that the authorities have to come and get you?

Hmm, how to summarize this one. Okay, so there’s this guy named Earl. Earl is in his 40s, is nearly deaf (he wears a hearing aid), is extremely racist, and has a young daughter who’s also deaf. Earl spends his weekends playing a Confederate soldier in Civil War recreations.

Earl and his friends are off to one of these recreations when a black man cuts them off in traffic. This man’s name is Malcom, an academic who’s trying desperately to get into Harvard. At the next stoplight, Earl and his racist buddies, in their Confederate uniforms, get out and OVERTURN Malcom’s car with him in it.

Later, after the recreation, the curmudgeon-y Earl meets up with his ex-wife, Myra, and keeps complaining about this guy she’s been hanging out with, Rob. Later that evening, when the sun goes down, Earl takes his hearing aid off, and his whole demeanor changes. He’s now… Rodeo Rob!

Rodeo Rob, according to Rodeo Rob, is from the future, 2525 to be exact, where he lives on the moon. He’s time travelled back here to, I guess, help humanity. He’s also fallen in love with Myra, and Myra him. Of course, Myra must wake up every morning to Rodeo Rob becoming Earl again, a man she detests.

In the meantime, Malcom, our friend from the overturned car, becomes fascinated with Earl’s split-personality, and figures if he can study him and discover what’s causing the split, maybe it will get him into Harvard.

So Malcom moves next door to Earl (what??) and begins helping him. Of course, Earl wants nothing to do with this, so Malcom has to navigate around that tricky obstacle, mostly conversing with Rodeo Rob. But the ultimate goal is to bring Earl and Rodeo Rob back into one personality. It’s just a matter of which personality that will be.

When trying to separate your writing from everyone else’s writing, tone is one of the few ways you can do it. If you can mix the tone of, say, a comedy, with the stagey feel of the theater, you get Wes Anderson. If you can mix the tone of a documentary with the tone of a sci-fi pic, you get District 9. Put succinctly, mixing tones is a great way to stand out.

But there are some notes that just don’t sound right together. Trying to mix a goofy split-personality comedy, a la “Me, Myself, and Irene” with a serious look at racism? I’m just not sure how you make that work. And when tone is mixed incorrectly, it doesn’t matter what else you do. The script is never going to feel right.

If that analysis is too technical for you, I’ll put it layman’s terms: This script is f*cking weird.

Part of the problem is that Gilligan can never make a restrained choice. He always has to go to level 100 on the scale. For example, Earl’s alternate personality can’t just be the opposite of him (liberal and tolerant), he has to be the opposite of him BUT ALSO BELIEVE HE’S FROM THE YEAR 2525! When Malcom wants to study Earl and his disorder, he can’t do it from his office, he has to move next door to him???

The moment where I knew Gilligan had gone off his rocker, is when he shows us the backstory for what happened to Earl’s young daughter, who also has a hearing problem.

Now I assumed her hearing issue was a result of genetics. Oh no. We find out that a few years back, when Earl was drunk, he dressed up in a KKK sheet to go and scare a group of black people who were swimming in the pool. He brought with him a stick of dynamite to show how serious he was.

What he didn’t know, because he was wasted, was that his daughter was swimming in the pool as well. Well, Earl fell in the pool, the dynamite went off, and since sound travels more prominently through water (or so we’re told), both he and his daughter were turned deaf by the blast. That’s the backstory for them losing their hearing. I kid you not.

Further evidence that Gilligan was smoking the good stuff when he wrote this was a random dream sequence (which included a shark) from the point of view of the daughter. Because why not? The main storyline’s going along. You’ve shown the daughter three times up to this point. Why not hop into her head for a dream sequence? Another strange choice was Malcom being an organ transplant courier. In fact, on the day our Confederates flip his car, he’s carrying two corneas. What??

Three-quarters of the way through the screenplay, Earl’s extremely racist best friend, Booth, burns a cross in his front yard. I mean can we really write a comedy today with the KKK, the N-word, and burning crosses? I suppose the world was a different place back in 1990 when Gilligan first wrote this, but it wasn’t THAT different. I don’t see how someone could look at this and say it was a good idea.

I mean, I commend Gilligan for trying something different, but this feels like one of those early scripts a screenwriter never gives up on that they probably should. We’ve all got those. The nostalgia and bullheadedness keep us coming back to them. I loved Gilligan’s early-days pilot for that cop show he made for CBS. This? This is just… out there dude.

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s a reason screenwriting software defines the non-dialogue section of text as “action.” It’s because that’s where you want to write ACTION. “Joe slams his fist down.” “Frank dashes over to his car.” “Carol spins to see the car coming at her.” Too many writers, however, think this section is called “description.” They like to use it for lines like, “Joe’s long hair never looks out of place. It’s like he keeps a personal stylist with him wherever he goes.” “Nearly everything in Frank’s apartment is green. It’s almost forest-like in its appearance.” “Carol crosses the city street, which is populated with early-morning commuters who haven’t had their lattes yet.” Obviously, you’re going to need to describe things in a script. And in small doses, the above examples are fine. It’s when that’s all you write where it becomes a problem. As a general rule, 80% of what you write in the action section should be ACTION, should be THINGS HAPPENING. — The reason Gilligan’s script was 130 pages was because it was deluged with unnecessary description. It made this one of the hardest scripts to get through all year. (note: There are exceptions to this action/description ratio, of course, but it’s almost always true)